Carl Gustav Carus stands as a remarkable figure in the intellectual and artistic landscape of 19th-century Germany. Born on January 3, 1789, in Leipzig, and passing away on July 28, 1869, in Dresden, Carus was a true polymath whose endeavors spanned medicine, physiology, natural philosophy, psychology, and, notably, landscape painting. His life and work offer a fascinating insight into the Romantic era's quest to unify science, art, and the human spirit. Unlike many of his contemporaries who specialized in a single field, Carus sought to find the underlying connections between disparate areas of knowledge, believing that a deep understanding of nature was essential for both scientific inquiry and artistic expression. He was not merely a dilettante dabbling in various pursuits; rather, he achieved recognized excellence in multiple domains, leaving a legacy that continues to be explored and appreciated.

Early Life and Formative Education

Carl Gustav Carus was born into a world on the cusp of significant change. His father, Gustav August Carus, was a dyer, and his mother was Christiana Elisabeth. Leipzig, his birthplace, was a vibrant center of commerce, publishing, and intellectual life, home to a renowned university. This environment likely fostered young Carus's inquisitive mind. His early education provided him with a strong foundation, and he soon demonstrated a prodigious intellect and a wide range of interests.

He enrolled at the University of Leipzig, initially pursuing studies that would prepare him for a career in the sciences. His academic journey was marked by diligence and a thirst for knowledge. He delved into chemistry, botany, and physics, but it was medicine and natural philosophy that particularly captured his attention. These fields, in the early 19th century, were often intertwined with broader philosophical questions about life, nature, and the human condition, aligning perfectly with the burgeoning Romantic sensibilities of the time. His formal medical training culminated in 1811 when he earned his Doctor of Medicine degree, a testament to his academic prowess in this demanding field.

A Distinguished Medical and Scientific Career

Following his doctorate, Carus embarked on a distinguished career in medicine and academia. He served as an anatomy lecturer at the University of Leipzig, where he honed his understanding of the human form – knowledge that would later subtly inform his artistic and philosophical work on human physiognomy. His expertise was soon recognized beyond Leipzig.

In 1814, Carus was appointed Professor of Obstetrics at the newly established surgical-medical academy in Dresden, and shortly thereafter, he became the director of the city's maternity hospital. Dresden, the capital of Saxony, was a major cultural hub, often referred to as "Florence on the Elbe," and it provided Carus with a stimulating environment. He was a dedicated physician and a respected teacher, contributing significantly to medical education and practice. His scientific inquiries were not limited to medicine. He made notable contributions to comparative anatomy, particularly in entomology, conducting pioneering experimental research.

One of his most significant scientific contributions was the development of the "vertebrate archetype" concept. This idea, which proposed an idealized, fundamental plan underlying the structure of all vertebrate animals, was an important precursor to later evolutionary theories and is acknowledged to have influenced thinkers like Charles Darwin. Carus's scientific mind was always seeking patterns, underlying principles, and the interconnectedness of living things. His scientific achievements were recognized with honors such as the Saxon Albert Grand Cross, and he was elected as a member of numerous prestigious scientific and artistic societies, reflecting the high esteem in which he was held by his peers.

The Foray into Art: Embracing Romanticism

Alongside his demanding scientific and medical career, Carus cultivated a deep passion for art, particularly landscape painting. He was largely self-taught as a painter, but his approach was anything but amateurish. His artistic development was profoundly shaped by the prevailing Romantic movement, which emphasized emotion, individualism, the sublime power of nature, and a spiritual interpretation of the natural world.

Carus did not see his scientific pursuits and artistic endeavors as separate or conflicting. Instead, he viewed them as complementary ways of understanding and engaging with the world. His scientific training in observation and anatomy provided him with a keen eye for detail and structure, while his Romantic sensibility allowed him to imbue his depictions of nature with emotional depth and philosophical meaning. He sought to capture not just the outward appearance of a landscape, but its inner life, its "soul."

His connection with the literary giant Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was particularly influential. Carus maintained a long correspondence with Goethe, who himself was deeply interested in the intersection of art and science, particularly in his studies of color theory and morphology. Goethe's holistic view of nature and his emphasis on intuitive understanding resonated with Carus and undoubtedly encouraged his artistic pursuits. Carus even authored a biography of Goethe, further underscoring their intellectual kinship. This connection placed Carus firmly within the intellectual elite of the German Romantic movement.

Friendship and Artistic Dialogue with Caspar David Friedrich

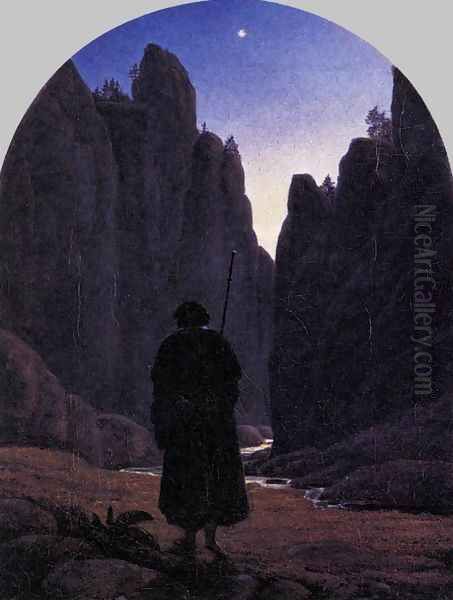

Perhaps the most significant artistic relationship in Carus's life was his friendship with Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), the preeminent landscape painter of German Romanticism. Carus met Friedrich around 1816 or 1817 in Dresden, where Friedrich was a leading figure in the artistic community. For about a decade, Friedrich became a mentor to Carus, guiding his artistic development and profoundly influencing his aesthetic principles and painting techniques.

Friedrich was known for his allegorical landscapes, imbued with spiritual symbolism and a sense of melancholy contemplation. He encouraged Carus to look deeply into nature and to paint from inner feeling rather than mere outward imitation. They would often take walks together, discussing art and nature, and Friedrich's studio practices and teaching methods left an indelible mark on Carus. Carus's writings provide valuable insights into Friedrich's personality and artistic process, describing his friend's often solitary existence, his intense dedication to his art, and even periods of profound artistic dissatisfaction that reportedly led Friedrich to contemplate suicide.

Carus also documented the controversy surrounding Friedrich's iconic painting, The Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar) (1808), which challenged traditional religious iconography by placing a crucifix in a natural landscape setting, sparking a debate led by the critic Basilius von Ramdohr. While Carus eventually developed his own distinct artistic voice, moving somewhat away from Friedrich's more overtly symbolic and melancholic style, the influence of his mentor remained evident throughout his career, particularly in his treatment of light, atmosphere, and the emotional resonance of landscape. Other artists in Friedrich's circle in Dresden, such as the Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857), who also became a close friend of Friedrich, contributed to the vibrant artistic milieu that Carus experienced.

The Grand Tour and Its Impact on Artistic Vision

Like many artists and intellectuals of his time, Carus undertook a "Grand Tour," a journey that significantly broadened his artistic and personal horizons. In 1827-1828, he accompanied Prince Frederick Augustus II of Saxony (who later became King) on a tour of Italy and Switzerland. This experience was transformative for Carus as a landscape painter.

The dramatic Alpine scenery of Switzerland, with its towering peaks and vast panoramas, offered new subjects and a different kind of sublime from the more familiar landscapes of Germany. In Italy, he encountered the rich artistic heritage of the Renaissance and antiquity, as well as the luminous Mediterranean light and picturesque scenery that had captivated artists for centuries. He meticulously documented his travels, and the sketches and observations he made during this period provided a wealth of material for later paintings.

While in Rome, Carus encountered a different artistic environment. He recorded his sometimes critical impressions of contemporary Roman artists, occasionally finding their work lacking in the depth and innovation he valued. Nevertheless, the Italian journey enriched his palette, refined his understanding of composition, and expanded his repertoire of landscape motifs. Works created after this tour often reflect a greater sense of light and space, and a more nuanced appreciation for geological formations and atmospheric effects, all filtered through his Romantic sensibility.

Carus's Artistic Philosophy: Erdlebenkunstmalerei and the Nine Letters

Carus was not only a practitioner of art but also a significant theorist. His most important contribution to art theory is his series of essays, Neun Briefe über Landschaftsmalerei (Nine Letters on Landscape Painting), written between 1815 and 1824 and published in 1831. This work is considered a foundational text of German Romantic landscape painting theory.

In these letters, Carus articulated his vision of "Erdlebenkunstmalerei," which can be translated as "earth-life painting" or "geognostic landscape painting." This concept emphasized the importance of a deep, scientific understanding of the earth's structure and natural processes – geology, botany, meteorology – as a basis for landscape art. However, this was not a call for dry, purely objective representation. Instead, Carus believed that by understanding the inner workings of nature, the artist could more profoundly convey its spiritual and emotional significance. He argued that art should be a "contemplation of the divine in nature," and that the landscape painter's task was to reveal the "secret life" of the earth.

His theory sought to bridge the perceived gap between the empirical observation championed by science and the subjective, emotional experience central to Romanticism. He encouraged artists to study nature meticulously, but then to synthesize these observations with their inner feelings and philosophical insights. This approach distinguished his ideas from earlier, more idealized landscape traditions, such as those of Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) or Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), and also from the more picturesque or topographically focused modes of landscape painting. Carus's ideas resonated with other Romantic thinkers and artists who sought a more profound engagement with the natural world, including, in different ways, English contemporaries like John Constable (1776-1837) and J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), who also combined close observation with expressive power.

Key Artistic Works: A Synthesis of Science and Soul

Carl Gustav Carus produced a significant body of work, primarily oil paintings and drawings, that exemplified his artistic theories. His landscapes are characterized by their careful observation of natural detail, their sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and their evocative, often contemplative moods. While influenced by Friedrich, Carus's paintings generally possess a calmer, more harmonious quality, reflecting his scientific understanding of natural order alongside a Romantic appreciation for nature's beauty and mystery.

Among his notable works is Riesengebirge (Giant Mountains), depicting the mountain range on the border of Bohemia and Silesia. Such mountain scenes allowed him to explore the geological structures he studied, while also conveying the sublime grandeur of nature. These works often feature expansive views, meticulous rendering of rock formations, and a keen sense of atmospheric perspective.

Gothic Church in Moonlight (various versions exist) is a theme that clearly echoes Friedrich, yet Carus brings his own sensibility to it. The interplay of moonlight, shadow, and ancient architecture evokes a sense of history, spirituality, and the passage of time – all key Romantic concerns. Similarly, Ruins of Eldena Abbey, another subject famously painted by Friedrich, shows Carus engaging with the Romantic fascination for ruins as symbols of transience and the enduring power of nature.

His travels are reflected in works like Balcony Room with View of the Bay of Naples (c. 1829-30). This painting employs a common Romantic device of a view framed by an interior, suggesting a contemplative observer and highlighting the contrast between the human realm and the vastness of nature. The luminous Italian light and the picturesque bay are rendered with a sensitivity honed by his direct experience.

Tintern Abbey (c. 1844), depicting the famous Welsh ruin, shows Carus's engagement with subjects that also inspired British Romantics like William Wordsworth and Turner. It underscores the shared European fascination with historical sites and their integration into the natural landscape. Other significant paintings include Vineyards in Spring at Pillnitz, showcasing his attention to botanical detail and the changing seasons, and Rising Moon and Pine Trees, which again demonstrates his mastery of nocturnal scenes and the symbolic power of moonlight. A collaborative work, Wanderer on the Mountaintop, Pilgrim's Rest, created with Friedrich, highlights their shared artistic concerns. Even smaller, more intimate works like Woman in Aerial Soliloquy reveal his interest in contemplative states.

Carus's paintings, often modest in scale, are rich in detail and imbued with a quiet intensity. They invite the viewer to share in his deep appreciation for the natural world, an appreciation informed by both scientific knowledge and profound emotional engagement. His approach can be seen as part of a broader German artistic lineage that valued close observation of nature, stretching back to artists like Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), albeit reinterpreted through a Romantic lens.

Philosophical and Psychological Contributions

Carus's intellectual curiosity extended deeply into philosophy and the nascent field of psychology. His medical background, particularly his work in physiology and anatomy, provided a foundation for his inquiries into the human mind and its relationship to the body. He was influenced by German Idealist philosophers and by the Naturphilosophie (nature philosophy) of figures like Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854), which sought to understand nature as a dynamic, unified organism.

One of his most important philosophical works was Symbolik der menschlichen Gestalt (Symbolism of the Human Form, 1853). In this book, Carus explored the idea that physical appearance, or physiognomy, could reveal aspects of an individual's inner character and psychological state. While physiognomy as a science has since been largely discredited, Carus's work was part of a broader 19th-century interest in the connections between the physical and the psychological, and it demonstrated his holistic approach to understanding human beings.

More significantly, Carus is recognized as an important early theorist of the unconscious. In his work Psyche: Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Seele (Psyche: On the Development of the Soul, 1846), he posited the existence of an unconscious realm of the mind that profoundly influences conscious thought and behavior. He distinguished between different levels of consciousness and emphasized the importance of the unconscious in dreams, instincts, and emotional life. While his concept of the unconscious differed in some respects from Sigmund Freud's later theories, Carus's work was a pioneering exploration of this crucial aspect of human psychology and is considered a significant precursor to psychoanalysis. His ideas in this area were remarkably prescient for their time.

Later Life, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Carl Gustav Carus remained active in his various fields until late in his life. He continued to paint, write, and contribute to scientific and medical discourse. As Royal Physician to the King of Saxony, he held a position of considerable prestige. His home in Dresden was a gathering place for artists, scientists, and intellectuals, reflecting his central role in the city's cultural life.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a scientist, his work in comparative anatomy and his early articulation of the vertebrate archetype were significant contributions. As a physician, he was respected for his skill and dedication. As a philosopher and psychologist, his explorations of the unconscious and the mind-body relationship were groundbreaking.

In the realm of art, Carus is remembered as a key figure in German Romantic landscape painting, both as an artist and a theorist. His Nine Letters on Landscape Painting provided an intellectual framework for a generation of artists seeking to combine scientific observation with spiritual insight. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as his mentor, Caspar David Friedrich, or other German Romantic painters like Philipp Otto Runge (1777-1810), whose allegorical works also explored deep philosophical themes, Carus's artistic contributions are increasingly recognized for their unique synthesis of scientific precision and Romantic sensibility. His influence can be seen in the work of later Dresden artists, such as Ludwig Richter (1803-1884), who, though developing a more idyllic and Biedermeier style, was part of the same artistic environment that Carus helped to shape. Even the great polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) can be seen as a distant spiritual ancestor, given their shared passion for understanding the world through both art and science.

Carus's enduring significance lies in his remarkable ability to bridge disciplines. In an age that was beginning to see increasing specialization, he embodied an older ideal of the universal scholar, yet he did so with a thoroughly modern, Romantic spirit. He demonstrated that scientific inquiry and artistic creation need not be mutually exclusive but can, in fact, enrich and inform one another, leading to a more profound and holistic understanding of the world and our place within it.

Conclusion: A Polymath for His Time and Ours

Carl Gustav Carus was a man of extraordinary talents and diverse achievements. His life's work represents a profound engagement with the major intellectual and artistic currents of the Romantic era. As a physician, scientist, philosopher, psychologist, and painter, he consistently sought to uncover the underlying unity of nature and the human experience. His landscape paintings, informed by his scientific knowledge and imbued with a deep spiritual sensibility, offer a unique window into the Romantic soul. His theoretical writings, particularly the Nine Letters on Landscape Painting, articulated a compelling vision for an art that was both intellectually rigorous and emotionally resonant.

In an age often characterized by fragmentation, Carus's pursuit of a harmonious vision, integrating the empirical and the intuitive, the scientific and the artistic, remains deeply relevant. He reminds us of the value of interdisciplinary thinking and the profound connections that can be found when we approach the world with both a keen observational eye and an open, contemplative heart. His legacy is not just in his individual achievements in various fields, but in the powerful example he set of a life dedicated to the holistic pursuit of knowledge and beauty.