Philipp Otto Runge stands as one of the most original and influential figures of German Romanticism, a multifaceted artist whose brief life blazed with creative intensity. Born on July 23, 1777, and passing away prematurely on December 2, 1810, Runge was not only a painter and printmaker of profound sensitivity but also a pioneering color theorist and writer. Alongside his contemporary Caspar David Friedrich, he defined the spiritual and aesthetic landscape of Northern German Romantic art, leaving behind a legacy that continues to resonate. Though his artistic career spanned little more than a decade, his visionary works and theoretical insights marked a significant departure from Neoclassicism, exploring the symbolic depths of nature, human life, and the cosmos.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Runge was born in Wolgast, a small town in Swedish Pomerania on the Baltic coast, into a family of shipbuilders and merchants. This background, emphasizing practicality and perhaps a certain closeness to the elemental forces of sea and sky, subtly informed his later worldview. His childhood was marked by illness, possibly tuberculosis, which led to periods of convalescence and limited formal schooling, perhaps fostering an introspective nature and a reliance on self-education. Initially destined for a commercial career, he moved to Hamburg in 1795 to apprentice with his elder brother, Johann Daniel Runge, who ran a shipping company.

It was in the vibrant mercantile city of Hamburg that Runge's artistic inclinations truly blossomed. He began taking drawing lessons, initially with Heinrich Joachim Herterich, and his passion quickly overtook his commercial pursuits. His brother Daniel, recognizing his talent and dedication, became a crucial supporter, both financially and emotionally, throughout Runge's short life. Encouraged, Runge decided to pursue art formally. From 1799 to 1801, he studied at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, a significant center for Neoclassicism at the time. There, he encountered the works and teachings of artists like Jens Juel and Nicolai Abildgaard, absorbing technical skills while already formulating his own distinct artistic path that diverged from academic convention.

Dresden and the Romantic Circle

In 1801, seeking a more stimulating artistic environment aligned with emerging Romantic ideals, Runge moved to Dresden. This city was a crucible for the early German Romantic movement, attracting poets, philosophers, and artists eager to explore new modes of expression centered on emotion, spirituality, and the sublime power of nature. It was here that Runge formed pivotal relationships that would shape his artistic and intellectual development.

Most significantly, he met and befriended Caspar David Friedrich, the other towering figure of German Romantic landscape painting. Though their artistic temperaments differed – Friedrich's melancholic, atmospheric vistas contrasting with Runge's often brighter, symbolically dense compositions – they shared a deep spiritual connection to nature and a desire to imbue landscape with profound meaning. Their friendship, rooted in shared North German origins and artistic aspirations, provided mutual support in an era still largely dominated by Neoclassical tastes, represented in Dresden by figures like the portraitist Anton Graff. Runge also connected with key literary figures of Romanticism, notably the writer and translator Ludwig Tieck, whose interest in folklore, mysticism, and medieval art resonated with Runge's own explorations.

The Encounter with Goethe

A defining moment in Runge's intellectual life occurred in 1803 when he traveled to Weimar and met Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the preeminent figure of German letters and a keen amateur scientist with his own theories on color. Runge, already deeply immersed in his own investigations into the nature and symbolism of color, found a receptive, albeit sometimes critical, interlocutor in Goethe. They corresponded frequently, discussing art, philosophy, and particularly the science and aesthetics of color.

Runge shared his experiments and his developing concept of the "Farbenkugel" (Color Sphere) with Goethe. While Goethe was working on his own influential Theory of Colours (published 1810), which emphasized the physiological and psychological perception of color in opposition to Newtonian physics, Runge was developing a systematic, three-dimensional model aiming to map the relationships between hues, brightness, and saturation. Goethe encouraged Runge's artistic endeavors but remained somewhat skeptical of the systematic, almost mathematical approach Runge took to color theory. Despite their differing perspectives, the dialogue with Goethe, and exposure to the intellectual circle in Weimar which included figures like Friedrich Schiller, undoubtedly enriched Runge's thinking and solidified his commitment to integrating artistic practice with theoretical inquiry.

The Grand Vision: The Times of Day

Runge's most ambitious artistic project, conceived during his Dresden years, was the cycle known as Die Tageszeiten (The Times of Day). This series was intended as a monumental exploration of the cyclical nature of life, the cosmos, and the divine, expressed through the allegory of the four times of day: Morning, Day, Evening, and Night. Each part was envisioned not merely as a painting but as a component of a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – that would ideally incorporate architecture, poetry, and music to create an immersive, chapel-like environment for spiritual contemplation.

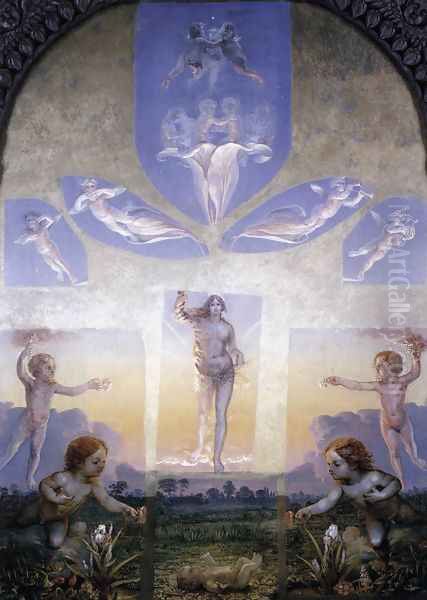

The cycle is rich with complex symbolism drawn from nature, Christian mysticism, and Neoplatonic thought. Flowers, particularly lilies and roses, symbolize purity, love, and divine creation. Infants or genii, often winged, represent souls, natural forces, or different stages of existence. Light itself plays a crucial symbolic role, charting the progression from dawn (birth, awakening) to noon (fullness of life), evening (decline, reflection), and night (death, mystery, potential rebirth). Runge completed a set of four intricate drawings for the series, which were published as engravings in 1805 and 1807, allowing his vision to circulate.

Of the intended large-scale paintings, only Morning (Der Morgen) was substantially realized. Completed in a first version around 1808 (now in the Hamburger Kunsthalle), it depicts a radiant dawn landscape presided over by Aurora, with a large lily blooming at the center, surrounded by symbolic infants and celestial light. It exemplifies Runge's unique blend of precise linearity, influenced perhaps by contemporary Neoclassical engravers like John Flaxman, and vibrant, symbolic color. The other parts of the cycle remained largely unrealized as paintings due to his early death, but the drawings and engravings stand as powerful testaments to his visionary scope, influenced by mystical thinkers like Jacob Böhme.

Mastery in Portraiture

While Runge is often celebrated for his symbolic landscapes and theoretical work, he was also an exceptionally gifted portrait painter. His portraits are characterized by a remarkable psychological acuity, a clarity of line, and an often unconventional approach to composition and color that sets them apart from the more formal academic portraiture of the time. He sought to capture not just the physical likeness but also the inner essence and spiritual disposition of his sitters.

Among his most famous portraits is The Hülsenbeck Children (Die Hülsenbecker Kinder, 1805-06). This depiction of the children of a Hamburg business partner breaks conventions by showing them outdoors, interacting dynamically within a carefully rendered garden setting that itself carries symbolic weight. The intense gaze of the youngest child, the protective stance of the eldest boy, and the vibrant natural details create a work of startling immediacy and charm, yet imbued with a deeper sense of childhood innocence and the burgeoning life force.

Runge also painted striking portraits of his family members, including his parents and his wife, Pauline Bassenge, whom he married in 1804. His self-portraits, such as the Self-Portrait in a Blue Coat (c. 1809-10), are powerful statements of artistic identity, using color and composition to convey introspection and creative intensity. His ability to combine intimate observation with a certain formal rigor places him among the most significant German portraitists of his era, comparable in skill, though different in style, to contemporaries like Anton Graff or Wilhelm Tischbein, famous for his portrait of Goethe in the Roman Campagna.

Pioneering Color Theory: Die Farbenkugel

Runge's fascination with color was not merely aesthetic; it was deeply philosophical and scientific. He believed color held the key to understanding the fundamental harmonies of the universe and sought to create a system that could map its intricate relationships. His research culminated in the publication of Die Farbenkugel, oder Construction des Verhältnisses aller Mischungen der Farben zueinander (The Color Sphere, or Construction of the Relationship of All Mixtures of Colors to Each Other) in 1810, the year of his death.

This work proposed the first three-dimensional model for organizing color. Runge envisioned a sphere where the pure, saturated hues (represented primarily by Red, Yellow, and Blue) were arranged around the equator. The North Pole represented pure White (light), and the South Pole represented pure Black (darkness). Colors on the surface of the sphere would transition towards white as they approached the North Pole (tints) and towards black as they approached the South Pole (shades). The central axis running through the sphere represented the grayscale, and colors within the sphere represented mixtures of hue, white, and black (tones).

Runge's Farbenkugel was a groundbreaking attempt to visualize the totality of color relationships in a logical, geometric structure. He also explored the symbolic and emotional qualities of colors, associating the primary triad of Blue, Red, and Yellow with the Christian Trinity, and linking colors to concepts like good and evil, or different times of day. Although aspects of his theory were later refined or superseded by figures like Michel Eugène Chevreul or Albert Munsell, Runge's Color Sphere was a landmark achievement, influencing subsequent color science, pedagogy, and artistic practice for generations.

Artistic Style and Romantic Ideals

Philipp Otto Runge's artistic style is unique and instantly recognizable. It often features strong, clear outlines, sometimes described as linear or even sharp, which may reflect the influence of engravings popular at the time, such as those by John Flaxman. However, this linearity is combined with a highly expressive and symbolic use of color. His compositions are meticulously planned, often employing symmetry and intricate arrangements of figures and natural elements to convey complex allegorical meanings.

His work is deeply rooted in the core tenets of German Romanticism. He shared with Friedrich and others a profound reverence for nature, seeing it not merely as a backdrop but as a living entity imbued with divine spirit. His art consistently sought to transcend the purely visible world, using natural forms – flowers, plants, light, children – as symbols for spiritual concepts like creation, innocence, transience, and eternity. This aligns him with the broader Romantic quest for subjective experience, emotional depth, and a connection to the sublime and the mystical, moving decisively away from the rationalism of the Enlightenment and the formal constraints of Neoclassicism. His visionary approach finds parallels in the work of artists like William Blake in England, who similarly combined intricate symbolism with personal spiritual insight.

Later Life and Legacy

After his formative years in Copenhagen and Dresden, and his pivotal encounter with Goethe, Runge settled primarily in Hamburg from 1803, although the disruptions of the Napoleonic Wars forced a temporary return to his hometown of Wolgast between 1805 and 1807. He married Pauline Bassenge in Dresden in 1804, and the couple had four children, the last born just after Runge's death. Despite the challenges of establishing himself financially as an artist and the turmoil of the times, Runge continued to work intensely on his paintings, drawings, engravings, and theoretical writings.

His lifelong frail health, however, eventually caught up with him. Suffering from tuberculosis (then often called consumption), his condition worsened significantly in his final years. Philipp Otto Runge died in Hamburg on December 2, 1810, at the tragically young age of 33. His brother, Johann Daniel, remained a steadfast champion of his legacy, collecting and eventually publishing his extensive writings and correspondence as Hinterlassene Schriften in 1840-41, ensuring that Runge's profound ideas would not be lost. Runge also practiced the delicate art of Scherenschnitte (paper cutting) throughout his life, creating intricate silhouettes, though many were sadly lost.

Enduring Influence

Although Runge's work was not widely known or fully appreciated during his short lifetime beyond a circle of fellow Romantics and intellectuals like Goethe, his influence proved to be profound and lasting. He and Caspar David Friedrich are now universally recognized as the twin pillars of German Romantic painting. Runge's emphasis on symbolism, expressive color, and the spiritual dimension of art anticipated later movements.

His work experienced a significant revival of interest in the early 20th century. German Expressionist groups like Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter saw in Runge a spiritual forefather. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, who explored the spiritual and emotional power of color, found inspiration in Runge's theoretical work and symbolic paintings. Paul Klee explicitly engaged with Runge's color theory in his own pedagogical writings at the Bauhaus. The mystical and visionary qualities of Runge's art also resonate in the work of later artists like Marc Chagall. While contemporary religious artists like the Nazarenes (e.g., Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr) shared a desire for spiritual renewal in art, Runge's approach was more personal, mystical, and integrated with nature.

Conclusion

Philipp Otto Runge remains a fascinating and pivotal figure in art history. In just over a decade of intense creative activity, he produced a body of work remarkable for its originality, intellectual depth, and spiritual conviction. He pushed the boundaries of painting, printmaking, and portraiture, infusing them with the ideals of Romanticism. His ambitious Times of Day cycle stands as a unique monument to the Romantic desire to synthesize art, nature, and spirituality. Furthermore, his Farbenkugel marked a crucial step in the systematic understanding of color, bridging the gap between artistic intuition and scientific inquiry. As a painter, theorist, and visionary, Philipp Otto Runge forged a unique path, leaving an indelible mark on German art and continuing to inspire those who seek deeper meaning in the interplay of color, form, and the human spirit.