Carl Irmer (1834-1900) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century German art. A dedicated landscape painter, he was intrinsically linked to the Düsseldorf School of painting, an institution and artistic movement that shaped the trajectory of German art and influenced artists far beyond its national borders. Irmer's oeuvre is characterized by its sensitive portrayal of nature, often imbued with the melancholic and atmospheric qualities synonymous with German Romanticism, yet also displaying a keen observational skill that captured the specific character of the diverse landscapes he depicted. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents, educational practices, and evolving aesthetics of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Düsseldorf

Born in Babitz, in the district of Stendal, Prussia (now part of Germany), in 1834, Carl Georg Ludwig Irmer's artistic journey began in an era of profound cultural and political change across Europe. The mid-19th century saw the consolidation of Romantic ideals in the arts, even as new movements like Realism began to challenge established conventions. For an aspiring painter in the German states, the Düsseldorf Academy of Art (Kunstakademie Düsseldorf) was a beacon, renowned for its rigorous training and its influential faculty.

Irmer enrolled at the Düsseldorf Academy, a pivotal decision that would shape his entire career. The Academy, under the directorship of figures like Wilhelm von Schadow, had become a leading center for art education, attracting students from across Germany, Scandinavia, Russia, and even the United States. Here, Irmer would have been immersed in a curriculum that emphasized meticulous drawing, anatomical study, and a deep respect for the traditions of Western art. In the realm of landscape painting, the Academy was particularly distinguished.

The Düsseldorf School and Its Influence

The Düsseldorf School of painting, to which Irmer belonged, was not a monolithic entity but rather a broad movement encompassing various styles and subjects. However, its landscape painters were particularly celebrated. They were known for their detailed, often dramatic, and emotionally resonant depictions of nature. Artists like Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, a key professor of landscape painting at the Academy during Irmer's formative years, championed a style that combined careful observation of nature with an idealized, often narrative, composition. Schirmer's influence, and that of the broader Düsseldorf ethos, would have been profound.

Other prominent figures associated with the Düsseldorf School, whose work and teachings would have formed the artistic environment for Irmer, include Andreas Achenbach, known for his dramatic seascapes and Nordic scenes, and his brother Oswald Achenbach, who became one of Irmer's direct mentors and was celebrated for his sun-drenched Italian landscapes. Carl Friedrich Lessing was another towering figure, known for his historical landscapes that often carried strong Romantic and nationalistic undertones. The presence of such diverse yet accomplished talents created a vibrant, competitive, and stimulating atmosphere for young artists like Irmer.

Oswald Achenbach: A Pivotal Mentorship

Carl Irmer's relationship with Oswald Achenbach (1827-1905) was particularly significant. The provided information indicates that Irmer was a student of Achenbach. Oswald Achenbach, himself a student of Schirmer, developed a distinctive style characterized by a brighter palette and a more painterly approach than some of his more strictly Romantic predecessors. He was renowned for his depictions of Italian life and scenery, capturing the warmth and vibrancy of the Mediterranean.

While Irmer's subject matter often focused on more northern climes, Achenbach's emphasis on light, color, and atmospheric effect likely left a lasting impression on his student. The collaborative trips to the Harz Mountains, undertaken by Irmer with Oswald Achenbach and F.G. Ude, further underscore this close working relationship. These excursions provided opportunities for direct study from nature, shared artistic exploration, and the kind of camaraderie that often fosters artistic growth. The painting Der Bodekessel, a product of these trips, exemplifies this collaborative spirit and shared interest in capturing the sublime beauty of the German wilderness.

The Romantic Vein: Style and Thematic Concerns

Irmer's artistic style is firmly rooted in the traditions of German Romanticism, a movement that emphasized emotion, individualism, and the glorification of the past and nature. His works often feature elements characteristic of this school: mist-shrouded hills, ancient forests, crumbling castles, and ruins. These motifs were not merely picturesque; they were imbued with symbolic meaning, evoking a sense of history, transience, and the sublime power of nature.

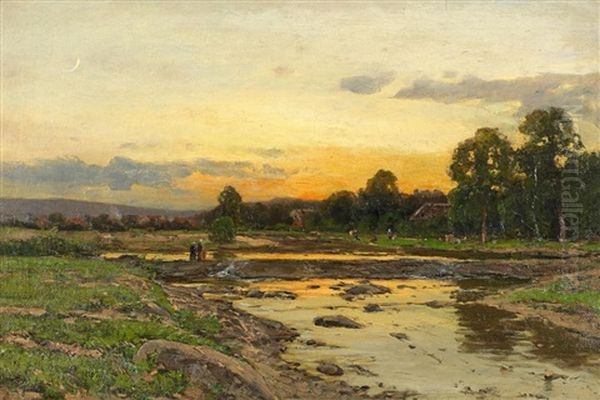

The influence of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), the preeminent German Romantic landscape painter, is palpable in the mood and atmosphere of many of Irmer's works. Friedrich's ability to transform landscapes into spiritual allegories, his use of contemplative figures, and his mastery of light and shadow set a high bar for subsequent generations. While Irmer may not have directly replicated Friedrich's overtly symbolic iconography, the shared sensibility for nature's evocative power is evident. Irmer’s landscapes often convey a quiet introspection, a sense of solitude, or the awe-inspiring grandeur of the natural world. He was particularly adept at capturing specific times of day – dawn, dusk, or the soft light of a new moon – to enhance the emotional resonance of his scenes.

Notable Works: A Journey Through Irmer's Landscapes

Carl Irmer's body of work, though perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries, includes a range of compelling landscapes that showcase his skill and artistic vision.

Dünenlandschaft an der Nordsee (Dune Landscape on the North Sea), dated 1858, is an early example that highlights his interest in the coastal regions of Germany. One can imagine this work capturing the stark beauty of the dunes, the play of light on sand and sea, and perhaps the vastness and elemental power of the North Sea environment. Coastal scenes were popular among Düsseldorf painters, offering opportunities to depict dramatic weather effects and the interplay of land, sea, and sky.

Stadtansicht Düsseldorf (City View of Düsseldorf), also from 1858, demonstrates his ability to tackle urban landscapes. Such views were often more than topographical records; they could celebrate civic pride, depict the harmony (or contrast) between urban development and nature, or capture the unique atmosphere of a city. Given Düsseldorf's importance as an art center, a view of the city by one of its prominent artists would have held particular interest.

Wittstock/Dosse - Düsseldorf Stadtansicht (1858) likely refers to a similar or related city view, perhaps focusing on a specific aspect or perspective of Düsseldorf, or it could be a work depicting Wittstock an der Dosse, a town in Brandenburg, before a Düsseldorf city view. The dual titling suggests a connection or a series.

Sylter Bauernhof (Farmstead on Sylt), dated 1850 (though this date might be slightly early if his main Düsseldorf period started later, or it could be an early work or a misattribution of date in the source), points to his interest in rural and vernacular subjects. The island of Sylt, with its distinctive thatched-roof houses and windswept landscapes, provided rich material for artists seeking authentic, unspoiled scenes.

Neumond (New Moon) and Abendstimme am Waldrand mit Schäfer (Evening Voice at the Edge of the Forest with Shepherd) are titles that strongly evoke the Romantic sensibility. Neumond would likely feature a subtle, crepuscular light, perhaps with a landscape bathed in the soft glow of the emerging moon, creating a mood of quiet contemplation or mystery. Abendstimme am Waldrand mit Schäfer suggests a pastoral idyll, a scene of rustic tranquility at twilight, possibly with a shepherd guiding his flock – a timeless motif symbolizing peace and harmony with nature.

A particularly interesting piece mentioned is a sketch depicting the artist Eugène Dücker (1841-1916) painting at his easel on the Baltic coast, around 1885. Dücker, another prominent figure of the Düsseldorf School who eventually succeeded Oswald Achenbach as professor of landscape painting, was a contemporary and colleague. This sketch not only provides a glimpse into the working methods of artists – painting en plein air (outdoors) – but also highlights the collegial relationships within the Düsseldorf artistic community. It’s a moment of artistic life captured, showing one artist observing another in the act of creation.

The work Der Bodekessel, created during excursions in the Harz Mountains with Oswald Achenbach and F.G. Ude, would have depicted a specific, dramatic location in the Bode Gorge. The Harz Mountains, with their rugged terrain, deep forests, and historical associations (including connections to Goethe's Faust), were a popular destination for Romantic artists seeking sublime and picturesque scenery.

Travels and the Expansion of Artistic Horizons

Like many artists of his time, Irmer undertook travels to gather subject matter and broaden his artistic experience. The provided information notes that he traveled in Germany, Austria, France, and Belgium for sketching. These journeys were essential for a landscape painter. Direct observation of different terrains, light conditions, and architectural styles enriched an artist's visual vocabulary and provided fresh inspiration.

His travels within Germany would have allowed him to explore diverse regions, from the coasts of the North and Baltic Seas to the mountains of the Harz and the picturesque river valleys. Austria would have offered Alpine scenery, while France and Belgium presented different landscape traditions and perhaps exposure to emerging artistic trends, such as the Barbizon School in France, whose members like Théodore Rousseau and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot were pioneering a more naturalistic approach to landscape painting. While Irmer remained largely within the Düsseldorf tradition, exposure to other European art scenes would have undoubtedly informed his perspective.

Collaborations and Professional Network

The art world of the 19th century, particularly within an academic center like Düsseldorf, was characterized by a network of professional relationships, including mentorships, collaborations, and friendly rivalries. Irmer's connections were vital to his development and career.

His student relationship with Oswald Achenbach was paramount. The fact that they also traveled and painted together, alongside F.G. Ude, indicates a mature, collegial bond that extended beyond the formal teacher-pupil dynamic. F.G. Ude, though less universally known today, was part of this circle, contributing to the artistic discourse and shared experiences that shaped their work.

His association with Eugène Dücker, as evidenced by the sketch, further illustrates the interconnectedness of the Düsseldorf artists. Dücker, who was slightly younger than Irmer, became known for his luminous coastal scenes and his move towards a more naturalistic, almost proto-Impressionistic style in his later career. Their shared time at the Düsseldorf Academy and their mutual interest in landscape would have fostered a professional respect and perhaps friendship.

The broader context of the Düsseldorf Academy meant Irmer was part of a community that included not only German artists but also international figures who came to study there. Americans like Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge passed through Düsseldorf, absorbing its techniques and philosophies before going on to become leading figures in the Hudson River School. While direct collaborations with all these figures are not documented for Irmer, he was undoubtedly part of this vibrant international artistic milieu.

Irmer as an Educator: Passing on the Tradition

Beyond his own artistic production, Carl Irmer played a role in shaping the next generation of artists through his teaching. He served as a professor of landscape painting at the Düsseldorf Academy, a position of considerable prestige and responsibility. This role placed him in a direct line of pedagogical descent from his own teachers, like Schirmer (indirectly) and Oswald Achenbach, and tasked him with upholding the standards and transmitting the techniques of the Düsseldorf landscape tradition.

Among his students were figures like Eduard Allport Ireland and Leopold Otto Strzelczyk. Strzelczyk, in particular, went on to become a notable landscape painter in his own right, suggesting that Irmer was an effective and influential teacher. His teaching would have likely emphasized rigorous observation, mastery of perspective and composition, and the ability to capture atmospheric effects – hallmarks of the Düsseldorf approach. He would have guided students in their studies from nature, their development of studio compositions, and their understanding of art history.

Legacy and Art Historical Position

Carl Irmer's position in art history is that of a distinguished representative of the Düsseldorf School of landscape painting, working within the broader currents of German Romanticism. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary status of a Caspar David Friedrich or the widespread international fame of an Andreas Achenbach, his contribution is significant. He produced a consistent body of high-quality work that captured the beauty and mood of the German landscape with sensitivity and skill.

His paintings continue to appear on the art market, indicating an enduring appreciation among collectors. Works like Dünenlandschaft an der Nordsee, Neumond, and Abendstimme am Waldrand mit Schäfer are testaments to his ability to evoke atmosphere and emotion. He successfully navigated the artistic environment of his time, balancing the tenets of Romanticism with the Düsseldorf Academy's emphasis on detailed realism and technical proficiency.

He can be seen as a vital link in the chain of German landscape painting, absorbing influences from masters like Friedrich and Schirmer, learning from contemporaries like Oswald Achenbach, and in turn, passing on his knowledge to his own students. His work reflects the period's fascination with nature, not just as a picturesque subject, but as a source of emotional and spiritual meaning. While the Düsseldorf School's influence waned with the rise of Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements, its impact on 19th-century art, particularly in Germany, Scandinavia, and America, was profound, and artists like Carl Irmer were integral to that legacy.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Irmer's Vision

Carl Irmer's life spanned a period of significant artistic evolution. He remained largely faithful to the Romantic and Realist traditions that defined the Düsseldorf School, creating landscapes that are both meticulously observed and deeply felt. His depictions of the German coasts, forests, and mountains, often bathed in the soft light of dawn or dusk, or veiled in mist, speak to a profound connection with the natural world.

Through his paintings, his collaborations, and his teaching, Irmer contributed to the rich artistic heritage of 19th-century Germany. He was a skilled craftsman and a sensitive interpreter of nature, whose works offer a tranquil yet evocative glimpse into the landscapes and artistic sensibilities of his era. While perhaps not a household name on the global stage, Carl Irmer remains an important figure for understanding the depth and breadth of the Düsseldorf School and the enduring power of German Romantic landscape painting. His art invites viewers to pause and appreciate the subtle beauties and profound emotions that can be found in the natural world, a message that continues to resonate today.