An Introduction to a Biedermeier Icon

Carl Spitzweg (February 5, 1808 – September 23, 1885) stands as one of the most beloved and significant painters of the German Romantic period. Particularly associated with the Biedermeier era, Spitzweg carved a unique niche for himself through his charming, humorous, and often gently satirical depictions of everyday life, especially focusing on the quirks and comforts of the German middle class. Born in Unterpfaffenhofen, near Munich, and spending most of his life in the Bavarian capital, he became a quintessential chronicler of his time, capturing its atmosphere with a keen eye for detail and a warm, albeit sometimes ironic, affection. Unlike many contemporaries who focused on grand historical narratives or sublime landscapes, Spitzweg found his inspiration in the intimate, the eccentric, and the seemingly mundane, transforming these scenes into enduring works of art that continue to resonate with viewers today. He is celebrated not just for his technical skill but for his unique perspective, offering a window into the soul of 19th-century German society.

From Pharmacy to Palette: An Unconventional Beginning

Spitzweg's journey to becoming a full-time artist was far from conventional. He was born into a relatively prosperous Munich family; his father, Simon Spitzweg, was a successful merchant involved in the spice trade, and his mother, Franziska Spitzweg (née Schmutzer), was the daughter of a wealthy wholesaler in the Upper Palatinate region. Reflecting the practical aspirations often held for sons of the bourgeoisie, Carl was initially destined for a career in pharmacy. He diligently pursued this path, beginning his training at the Royal Bavarian Court Pharmacy in Munich and later studying pharmacy, botany, and chemistry at the University of Munich. He successfully qualified as a pharmacist in 1832.

However, fate intervened. A period of illness forced him to convalesce, providing him with ample time for reflection and the pursuit of other interests. During this time, his passion for drawing and painting, previously a hobby, began to flourish. He started teaching himself the fundamentals of art, studying the works of old masters and honing his observational skills. A significant turning point came in 1833 when he received a substantial inheritance following the death of his father. This newfound financial independence freed him from the necessity of pursuing pharmacy as a career and allowed him to dedicate himself entirely to his true calling: art. He never looked back, embarking on a path defined by artistic exploration rather than pharmaceutical formulas.

Forging a Style: Self-Taught Talent and European Influences

Remarkably, Carl Spitzweg never received formal academic training in art. He was largely an autodidact, learning his craft through careful observation, relentless practice, and the study of other artists' works. Early in his artistic development, he showed an affinity for the Dutch and Flemish masters of the 17th century. He spent time copying paintings by artists known for their genre scenes and landscapes, likely absorbing lessons in composition, colour, and the depiction of everyday life from painters such as Adriaen Brouwer or David Teniers the Younger, whose portrayals of peasant life, albeit earthier than Spitzweg's later work, demonstrated the artistic potential of common subjects.

His inheritance enabled extensive travel, which proved crucial to broadening his artistic horizons. He journeyed to various European art centres, including Prague, Venice, Paris, London, and cities in Belgium. These trips exposed him to a wider range of artistic styles and contemporary movements. His visit to Paris in 1851, in the company of his friend and fellow painter Eduard Schleich the Elder, was particularly significant. There, he encountered the works of the Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña. The Barbizon artists' emphasis on realistic landscape painting, often imbued with a romantic sensibility and looser brushwork, left a noticeable mark on Spitzweg's later work, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere in landscapes.

Furthermore, his exposure to English landscape painters like John Constable and Richard Parkes Bonington, possibly during his London visit or through prints, likely reinforced his interest in capturing natural light and atmospheric effects. While remaining distinctly German and rooted in the Biedermeier sensibility, Spitzweg skillfully integrated these diverse influences into his own unique and instantly recognizable style, blending meticulous detail with a growing freedom in technique.

Painting the Biedermeier World

Spitzweg's art is inextricably linked to the Biedermeier period, a phase in Central European culture roughly spanning from the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) to the Revolutions of 1848. This era was characterized by a turning inward, a focus on the domestic sphere, the middle class, and the cultivation of Gemütlichkeit – a sense of coziness, comfort, and simple pleasures. Politically, it was a time of relative conservatism and censorship following the upheavals of the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras. Artistically, this translated into a preference for genre scenes, portraits, and landscapes over heroic or overtly political themes. The grand history painting favoured by academy figures like Peter von Cornelius or Wilhelm von Kaulbach in Munich held less appeal for the Biedermeier sensibility.

Spitzweg became one of the foremost visual interpreters of this world. His paintings often depict the quiet, ordered lives of the bourgeoisie – scholars in their studies, collectors admiring their treasures, families enjoying music. Yet, Spitzweg was more than just a passive recorder. His Biedermeier is often viewed through a lens of gentle irony. He subtly highlighted the sometimes narrow, self-satisfied, and eccentric aspects of this inward-looking society. His characters, while often endearing, can also appear slightly ridiculous in their pursuits and preoccupations. He captured both the comfort and the potential confinement of the Biedermeier ethos, making his work a nuanced commentary rather than simple documentation.

The Gentle Art of Satire: Spitzweg's Unique Vision

While rooted in the Biedermeier appreciation for the everyday, Spitzweg's work is distinguished by its pervasive humour and gentle satire. He possessed a unique ability to observe human foibles and depict them with a light touch, inviting amusement rather than harsh judgment. This humorous vein runs through much of his oeuvre, setting him apart from the more earnest or sentimental tendencies sometimes found in Biedermeier art. His satire was rarely biting or overtly political, unlike, for instance, the contemporary French caricaturist Honoré Daumier, whose lithographs offered scathing critiques of Parisian society and politics. Spitzweg's humour was quieter, more anecdotal, focused on the peculiarities of individual character types and situations within the small-town or middle-class milieu.

His contributions to the Munich-based satirical magazine Fliegende Blätter ("Flying Leaves") further attest to his comedic talents. He provided numerous illustrations for the publication, sharpening his skills in visual storytelling and caricature. In his paintings, the humour often arises from the juxtaposition of elements – a scholar oblivious to his chaotic surroundings, a sentry fast asleep at his post, or the slightly absurd intensity with which his characters pursue their hobbies. He masterfully used posture, facial expression, and carefully chosen details in the setting to convey the comedic or ironic essence of a scene, making viewers feel like they are sharing a private joke with the artist.

Eccentrics, Dreamers, and Daily Life: Recurring Motifs

Spitzweg's paintings are populated by a memorable cast of recurring character types, often representing figures slightly outside the mainstream or absorbed in their own worlds. Eccentric scholars, near-sighted bookworms lost in dusty libraries, absent-minded poets dreaming in drafty attics, and dedicated alchemists tinkering in cluttered laboratories are frequent subjects. These figures, often depicted with affectionate irony, seem to embody a retreat from the mundane realities of the world into intellectual or artistic pursuits, however impractical or outdated they might seem.

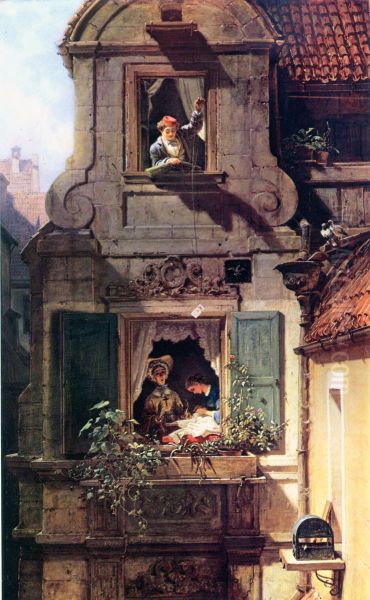

Other common figures include hermits and monks, often shown in idyllic natural settings, suggesting a romanticized view of contemplative life removed from societal pressures. Civil servants like postmen, night watchmen, and customs officials also appear, sometimes portrayed with a gentle mockery of bureaucratic routine or self-importance. Spitzweg was fascinated by these "originals," individuals defined by their passions, professions, or peculiar habits.

Beyond these character studies, Spitzweg also painted scenes of everyday life – lovers serenading beneath balconies, friends enjoying music, quiet moments in sunlit courtyards, or bustling scenes in narrow town alleys. His landscapes, while often serving as backdrops for his figures, also became increasingly important in their own right, particularly in his later career. He depicted the charming townscapes and rolling hills of Upper Bavaria with sensitivity to light and atmosphere, often imbuing them with a sense of peacefulness and romantic charm, sometimes reminiscent of the idyllic landscapes of Austrian Biedermeier painters like Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller.

Iconic Canvases: Exploring Spitzweg's Major Works

Several of Carl Spitzweg's paintings have achieved iconic status, becoming synonymous with his name and the Biedermeier era itself. Perhaps the most famous is The Poor Poet (Der arme Dichter), painted in several versions starting in 1839. It depicts a writer huddled in bed in a sparse, leaky attic room, quill pen in hand, surrounded by books and manuscripts, seemingly oblivious to his poverty and the umbrella shielding him from dripping water. The painting is a masterful blend of sympathy and irony, gently mocking the romantic ideal of the starving artist while also highlighting the harsh realities faced by creative individuals. Its immense popularity made it a target for theft; one version was stolen in 1989 and remains missing.

Another widely recognized masterpiece is The Bookworm (Der Bücherwurm), painted around 1850. This work shows an elderly scholar perched precariously atop a library ladder, completely absorbed in a book, holding others under his arm and between his knees. Bathed in the soft light filtering through an unseen window, he is the epitome of scholarly obsession, a figure both comical and endearing in his dedication. The detailed rendering of the towering bookshelves emphasizes the vastness of knowledge and the scholar's solitary immersion within it.

Other significant works include The Alchemist (c. 1860), showcasing Spitzweg's interest in scientific pursuits and cluttered interiors; The Serenade (Das Ständchen, c. 1850), a charming nocturnal scene capturing romantic Biedermeier sentiment; The Hypochondriac (Der Hypochonder, c. 1865), humorously depicting a man anxiously consulting medical texts; and numerous landscapes and townscapes that reveal his sensitivity to nature and architecture. Works like Threatening Passage (sketch, 1840s), Carpenter and the Balloon (c. 1850), and Washhouse (c. 1879) demonstrate his range in subject matter and his consistent eye for narrative detail and gentle humour.

Craftsmanship and Colour: Spitzweg's Artistic Technique

Despite being self-taught, Spitzweg developed a high degree of technical proficiency. His earlier works often display a meticulous, detailed finish reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch fine painters (Gerrit Dou might be another point of comparison). He paid close attention to the rendering of textures – wood grain, fabric folds, crumbling plaster, book bindings – which adds to the realism and charm of his interiors and townscapes. His compositions are carefully constructed, often using architectural elements like doorways, windows, and arches to frame the scene or lead the viewer's eye.

Spitzweg possessed a fine sense of colour. His palette often favoured warm, rich tones – deep reds, browns, ochres, and greens – creating a cozy and intimate atmosphere. He was particularly adept at depicting light, whether it be the soft, diffused light filtering into a scholar's study, the warm glow of lamplight in a nocturnal scene, or the bright sunshine illuminating a landscape. His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) contributes significantly to the mood and three-dimensionality of his paintings, perhaps reflecting his study of masters like Rembrandt van Rijn.

In his later works, influenced by his travels and exposure to artists like the Barbizon painters, his brushwork sometimes became looser and more fluid, particularly in his landscapes. He experimented with capturing fleeting atmospheric effects, moving towards a style that, while not Impressionistic, showed a greater interest in spontaneity and the optical effects of light and colour, prefiguring some aspects of later plein-air painting. He was also a proficient draftsman, producing numerous sketches and drawings, often as studies for his paintings.

Artistic Circles: Friendships and Collaborations

While often portrayed as a somewhat solitary figure absorbed in his work, Spitzweg did maintain connections within the Munich art scene. His most significant artistic friendship was with the Austrian-born painter Moritz von Schwind, who also settled in Munich. Schwind, known for his fairytale illustrations and romantic compositions often inspired by music and literature, shared Spitzweg's Biedermeier sensibility, though his style was generally more lyrical and less satirical. The two artists reportedly met frequently in Munich cafes from the 1840s onwards, engaging in discussions about art and music, reflecting the collegial atmosphere among some artists in the city.

Spitzweg also formed a close professional relationship and friendship with the landscape painter Eduard Schleich the Elder. Their skills complemented each other, leading to occasional collaborations. It is documented that Schleich sometimes painted the expansive skies in Spitzweg's landscapes, while Spitzweg would add the characteristic small figures (Staffage) to Schleich's landscape compositions. This partnership highlights the specialization and mutual respect that could exist among artists. Their joint trip to Paris and London in 1851 further cemented their bond and shared artistic exploration.

While perhaps not deeply involved in the formal structures of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, then dominated by figures associated with history painting and Neoclassicism like Peter von Cornelius or later Karl von Piloty, Spitzweg was certainly aware of the broader artistic currents. His work offers a distinct counterpoint to the grand academic style, focusing instead on the intimate and anecdotal, aligning him more closely with the Biedermeier spirit shared by artists like Schwind and, in the realm of landscape, Schleich. He also existed within the broader context of German Romanticism, which included profoundly different artists like the sublime landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich or the religiously inspired Nazarenes (Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr).

Journeys of Discovery: Spitzweg's European Travels

Travel played a vital role in shaping Carl Spitzweg's artistic perspective and technique. Freed by his inheritance, he undertook numerous journeys throughout Europe, seeking inspiration, studying art collections, and observing different landscapes and cultures. His travels took him beyond Bavaria to places like Prague, a city rich in history and picturesque architecture, and Venice, whose unique light and atmosphere captivated countless artists. He also visited Belgium, likely studying the Flemish masters he admired in their homeland.

The trip to Paris and London in 1851 with Eduard Schleich the Elder stands out as particularly influential. In Paris, exposure to the Barbizon school painters provided fresh impetus for his landscape painting, encouraging a more direct engagement with nature and a looser application of paint. In London, they visited the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations held in the Crystal Palace, a showcase of global technological and artistic achievement. They also likely took the opportunity to study the works of English landscape masters like John Constable and Richard Parkes Bonington, whose naturalism and atmospheric sensitivity resonated with their own artistic interests. These experiences abroad prevented Spitzweg's art from becoming overly provincial, infusing it with broader European currents while retaining its distinct German character.

Later Years and Enduring Fame

Carl Spitzweg continued to paint prolifically throughout his later life, remaining based in Munich. While his style evolved subtly, incorporating looser brushwork and a brighter palette in some later landscapes, he largely remained true to the themes and humorous spirit that had defined his earlier work. He enjoyed considerable popularity during his lifetime, with his paintings finding eager buyers among the middle class whose world he so affectionately depicted. His contributions to Fliegende Blätter also ensured his name was widely known.

He passed away in Munich on September 23, 1885, reportedly from a stroke, discovered peacefully in his apartment. While respected during his lifetime, his fame and critical appreciation arguably grew even stronger in the decades following his death. His works came to be seen as quintessential expressions of the Biedermeier era, capturing a specific moment in German cultural history with unparalleled charm and wit. Major museums, notably the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, began to acquire significant collections of his paintings, cementing his place in the canon of German art. His appeal transcended academic circles, making him one of Germany's most enduringly popular artists.

A Lasting Impression: Spitzweg's Legacy in Art and Culture

Carl Spitzweg's influence extends beyond the realm of painting. His unique blend of humour, charm, and gentle social observation has resonated through German culture. A notable example is the operetta or musical comedy Das kleine Hofkonzert ("The Little Court Concert"), composed by Edmund Nick with lyrics by Paul Verhoeven and Toni Impekoven, which premiered in 1935. The work was directly inspired by Spitzweg's paintings, aiming to capture their idyllic and humorous Biedermeier atmosphere. This demonstrates how his visual world provided fertile ground for other art forms.

While Spitzweg did not found a distinct school or have direct pupils who emulated his style in the way academic painters did, his impact lies in his validation of the everyday and the eccentric as worthy subjects for art. He showed that humour and charm could coexist with technical skill and insightful observation. His work provided an alternative to both the grandiosity of official academic art and the intense emotionalism found in other strands of Romanticism. In this sense, he helped broaden the scope of acceptable subject matter and tone in German art.

His paintings continue to be widely reproduced and admired, representing a comforting, albeit slightly idealized, vision of the past for many Germans. While later art movements, such as German Expressionism with artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, would react strongly against the perceived complacency of the Biedermeier world Spitzweg depicted, his work remains a vital part of Germany's artistic heritage, appreciated for its craftsmanship, humour, and unique window onto the 19th century.

Critical Perspectives: Evaluating Spitzweg's Place in Art History

Art historical assessment of Carl Spitzweg is generally positive, acknowledging him as a master of genre painting and a key figure of the Biedermeier era. Scholars praise his keen observational skills, his technical proficiency, his masterful use of colour and light, and, above all, his unique ability to infuse scenes of everyday life with humour and gentle satire. He is recognized for capturing the specific atmosphere and social nuances of his time with wit and affection. His portrayal of the eccentric individual finding solace or absorption in private pursuits is seen as a characteristic theme reflecting the Biedermeier retreat into the personal sphere.

However, his work has occasionally faced criticism or neglect within certain academic circles. Some critics have found his art overly anecdotal, charming but perhaps lacking the profound depth or dramatic intensity of other Romantic artists like Caspar David Friedrich or the socio-political engagement of Realists like Gustave Courbet in France. His focus on humour has sometimes led to his work being perceived as less "serious" than that of his contemporaries who tackled historical, mythological, or overtly emotional themes. The very popularity that makes him beloved by the public has sometimes made him suspect to critics wary of sentimentality or popular taste.

Despite these occasional reservations, the consensus recognizes Spitzweg's significant contribution. He is valued precisely for his unique perspective – his ability to find poetry and humour in the mundane, his gentle critique of bourgeois life, and his creation of a distinct and enduring visual world. His work is seen as an essential component of 19th-century German art, offering insights into the Biedermeier mentality and demonstrating a form of Romanticism focused on the intimate and the individual rather than the sublime or the heroic. His technical skill, particularly his handling of light and detail, is also widely acknowledged.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Carl Spitzweg

Carl Spitzweg remains one of Germany's most cherished artists, his work embodying the spirit of the Biedermeier era with unparalleled charm and wit. From his unconventional beginnings as a self-taught pharmacist-turned-painter, he developed a unique artistic voice, blending meticulous realism with romantic sensibility and a signature touch of gentle humour. His paintings offer a captivating glimpse into the world of 19th-century German middle-class life, populated by endearing eccentrics, diligent scholars, and quiet observers, all rendered with technical skill and affectionate irony.

Influenced by Dutch masters, contemporary European art movements like the Barbizon School, and the landscapes of his native Bavaria, Spitzweg forged a style that was both deeply personal and reflective of his time. His iconic works, such as The Poor Poet and The Bookworm, have transcended their era to become beloved images in German culture. While sometimes viewed as less "serious" than artists tackling grander themes, Spitzweg's focus on the intimate, the humorous, and the subtly satirical provides a valuable and enduring perspective on human nature and society. His art continues to delight viewers with its warmth, detail, and the gentle smile it seems to invite, securing Carl Spitzweg's lasting place in the history of art.