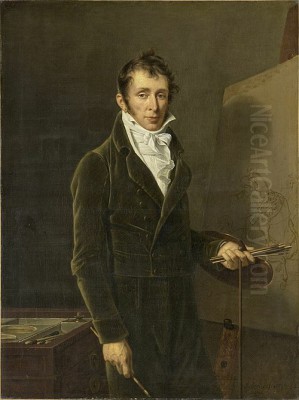

Antoine Charles Horace Vernet, universally known in the art world as Carle Vernet (1758-1836), stands as a pivotal figure in French art, bridging the transition from the structured elegance of Neoclassicism to the dynamic energy of Romanticism. Born into an artistic dynasty and living through one of France's most tumultuous and transformative periods, Vernet became renowned for his masterful depictions of horses, thrilling battle scenes, and insightful glimpses into contemporary life. His work not only captured the spirit of his age, from the final years of the Ancien Régime through the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Empire, and the subsequent monarchies, but also significantly influenced the trajectory of French painting, particularly through his celebrated son, Horace Vernet.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Carle Vernet was born in Bordeaux on August 14, 1758. Artistry was deeply ingrained in his lineage; he was the youngest son of the acclaimed marine and landscape painter Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714-1789), whose dramatic seascapes and tranquil landscapes had earned him international fame and royal patronage. Growing up in the shadow of such a prominent father provided Carle with an immersive artistic environment from his earliest years. He received his initial training within his father's studio, absorbing the fundamentals of drawing and composition.

Recognizing his son's burgeoning talent, Claude-Joseph entrusted Carle's formal education to Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié (1735-1784) around the age of eleven. Lépicié, a respected painter known for his historical subjects and genre scenes, provided Carle with rigorous academic training. Under Lépicié's tutelage, Vernet honed his skills, demonstrating a particular aptitude for drawing and a keen eye for detail, especially in rendering the animal form.

Vernet's ambition led him to compete for the prestigious Prix de Rome, the ultimate prize for aspiring French artists, which offered a funded period of study at the French Academy in Rome. After an earlier attempt, he finally secured the Grand Prix for painting in 1782. This victory enabled him to travel to Rome, the epicenter of classical antiquity and Renaissance mastery, a journey considered essential for any serious history painter at the time.

The Roman Experience and Shifting Focus

In Rome, Vernet immersed himself in the study of classical sculptures and the works of Renaissance giants like Raphael and Michelangelo, as well as Mannerist artists such as Giulio Romano. This exposure was intended to solidify his grounding in the Neoclassical tradition, emphasizing historical and mythological subjects rendered with clarity, order, and idealized forms. However, Vernet's time in Italy also ignited other passions.

He developed an intense fascination with horses and horsemanship, spending considerable time observing and sketching them. The vibrant life of the Roman streets and countryside, along with the popular horse races (Corso dei Barberi), captivated him perhaps more than the ancient ruins. This period marked a subtle but significant shift in his artistic inclinations. While respecting classical ideals, Vernet felt increasingly drawn towards a more naturalistic representation of the world around him, particularly the dynamic energy of animals and contemporary life.

His stay in Rome was not without personal turmoil. Vernet reportedly experienced a period of intense religious fervor, possibly bordering on a nervous breakdown, which concerned his father enough to recall him to Paris earlier than planned, around 1783. This episode, however, did not derail his artistic development; instead, it perhaps contributed to the emotional depth that would later infuse his more Romantic works.

Rise to Prominence: Revolution and New Directions

Upon returning to Paris, Carle Vernet sought to establish his reputation within the official art establishment, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. He worked diligently on his reception piece, the painting required for full membership. In 1788, he was officially accepted (agréé) and in 1789 presented his monumental work, The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus, depicting the Roman general's victory parade after conquering Macedon. This large-scale history painting, executed in the prevailing Neoclassical style, showcased his mastery of composition, anatomy, and historical detail, earning him acclaim at the Salon of 1789.

The outbreak of the French Revolution in the same year dramatically altered the social and artistic landscape. The old systems of patronage began to crumble, and artists had to navigate a dangerous and unpredictable political climate. The Reign of Terror brought personal tragedy to the Vernet family when Carle's sister, Marguerite Émilie Vernet (wife of the architect Jean-François Chalgrin, designer of the Arc de Triomphe), was guillotined in 1794. This devastating event profoundly affected Carle, reportedly causing him to temporarily abandon his art.

Despite the turmoil and personal loss, Vernet gradually resumed painting. The changing times also opened up new subject matter. While grand history painting continued, there was a growing market for scenes depicting contemporary events, military life, and the everyday pursuits of the citizenry. Vernet, with his innate talent for capturing movement and his love for horses, found fertile ground in depicting hunts, races, and elegant Parisians on horseback, subjects that resonated with both the remaining aristocracy and the emerging bourgeoisie.

Painter of the Empire: Documenting Napoleon's Era

Carle Vernet's career reached new heights during the Napoleonic era. His skill in depicting horses and military subjects perfectly aligned with the needs of a regime eager to glorify its leader and military triumphs. Napoleon Bonaparte himself admired Vernet's work, recognizing its potential for propaganda and historical documentation. Vernet received numerous commissions from the Emperor and the imperial administration.

He became one of the foremost visual chroniclers of Napoleon's campaigns. His most famous works from this period include the Battle of Marengo (c. 1801-1804) and the Morning of Austerlitz (1808). These paintings, while adhering to certain Neoclassical compositional principles in their scale and clarity, pulsed with a new energy and realism. Vernet meticulously researched uniforms and equipment, striving for accuracy, and excelled at conveying the chaos, drama, and equine power inherent in cavalry charges and battlefield maneuvers. He often depicted Napoleon himself, mounted on horseback, directing his troops with characteristic resolve.

In this role, Vernet worked alongside other prominent artists of the Empire, such as the leading Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), whose style was more severe and politically charged, and Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), another favored painter of Napoleon known for his more overtly Romantic and dramatic battle scenes. Vernet's contribution was distinct, marked by his unparalleled understanding of equine anatomy and movement, bringing a unique dynamism to the military genre. He also painted numerous studies of specific military units, like the Mamelukes of the Imperial Guard, exotic cavalrymen whose colourful attire and Arabian steeds fascinated Parisian society.

Master of the Horse

Above all else, Carle Vernet was celebrated as the preeminent painter of horses in France. His passion for equestrianism permeated his life and art. He was an accomplished rider himself, and this firsthand experience informed his depictions. Vernet possessed an almost scientific understanding of equine anatomy, musculature, and gait, which lent an extraordinary realism and vitality to his animals.

He portrayed horses in every conceivable context: charging into battle, galloping in races, leaping fences during hunts, parading elegantly in the Bois de Boulogne, or simply standing at rest. Unlike the somewhat idealized or stylized horses often seen in earlier art, Vernet's animals were individuals, captured with specific characteristics and palpable energy. His ability to render the sheen of a coat, the strain of a muscle, or the flick of a tail was unparalleled among his French contemporaries.

His dedication to equine accuracy invites comparison with the great English horse painter George Stubbs (1724-1806), though Vernet's style was generally more fluid and dynamic, less focused on the purely anatomical study that characterized much of Stubbs's work. Vernet's influence in this domain was profound, particularly on the younger generation of Romantic artists. Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), himself a passionate equestrian and admirer of Vernet, studied his work closely and pushed the depiction of equine power and drama even further in masterpieces like The Raft of the Medusa and his numerous horse studies.

Beyond the Battlefield: Genre, Caricature, and Printmaking

While renowned for military and equestrian scenes, Carle Vernet's artistic output was remarkably diverse. He possessed a keen sense of observation and a witty eye for social manners, which he applied to genre scenes depicting the fashionable life of Paris. He captured the elegance of high society, the bustling atmosphere of the city's streets, and the leisure activities of the well-to-do.

Vernet was also a gifted and prolific caricaturist. During the Directory period, he produced satirical prints mocking the exaggerated fashions of the Incroyables et Merveilleuses, the flamboyant dandies and socialites of the post-Terror era. Later, his series The English in Paris gently poked fun at the influx of British tourists visiting the French capital after the Napoleonic Wars, highlighting cultural differences and stereotypes with humour and sharp observation. These works reveal a lighter, more satirical side to his artistic personality.

Furthermore, Vernet embraced the burgeoning technique of lithography. Introduced in France in the early 19th century, lithography allowed for greater freedom of drawing directly onto the stone and facilitated the wider distribution of prints. Vernet was among the first major French artists to explore its potential, collaborating with pioneering printers like Godefroy Engelmann (1788-1839) and publishers such as François-Séraphin Delphée. He produced numerous lithographs covering his favourite themes – military types, horses, hunts, and scenes of daily life – making his art accessible to a broader audience and contributing significantly to the popularity of the medium.

Later Career and Legacy

Carle Vernet's career continued successfully through the Bourbon Restoration (1814-1830) and into the July Monarchy (1830-1848). Though the political winds shifted, his reputation as a master painter, particularly of horses, remained secure. He adapted to the changing tastes and patrons, receiving honours such as the Legion of Honour (1808) and membership in the Institut de France.

During the Restoration, he continued to paint equestrian portraits, hunting scenes, and historical subjects that appealed to the restored monarchy and aristocracy. After the July Revolution of 1830, he depicted King Louis-Philippe I in works such as The Duke of Orléans proceeding to the Hôtel de Ville, July 31, 1830, capturing a key moment of the new regime's establishment.

Perhaps Vernet's most significant legacy, beyond his own impressive body of work, was his influence on his son, Horace Vernet (1789-1863). Carle provided Horace with his initial training and instilled in him a similar passion for military subjects, horses, and contemporary history. Horace would go on to achieve even greater fame than his father, becoming one of the most celebrated and prolific painters of the 19th century, particularly known for his vast battle canvases and Orientalist scenes. The Vernet dynasty, begun by Claude-Joseph, thus continued its prominence in French art through Carle and Horace.

Carle Vernet passed away in Paris on November 27, 1836, leaving behind a rich and varied oeuvre that captured the essence of a dynamic era.

Artistic Style Revisited

Carle Vernet's style is characterized by its unique synthesis of Neoclassical principles and emerging Romantic sensibilities. From Neoclassicism, he retained a commitment to clear composition, anatomical accuracy, and often, grand historical or military themes. His drawing was precise, his lines clean and descriptive.

However, Vernet infused these structures with Romantic dynamism, energy, and a focus on contemporary reality. His work is notable for its sense of movement, particularly in the depiction of horses and battle scenes. He excelled at capturing fleeting moments and conveying atmosphere, whether the tension before a race, the chaos of combat, or the elegance of a social gathering. His use of colour became increasingly vibrant over his career, and his brushwork, while often detailed, could also be fluid and expressive. His keen observation extended to social satire in his caricatures, showcasing versatility beyond academic painting.

Conclusion

Carle Vernet occupies a crucial place in the history of French art. As the son of Claude-Joseph Vernet and the father of Horace Vernet, he was the central link in an extraordinary artistic dynasty. Living and working through decades of profound change, he adapted his art to reflect the shifting political and social currents, from the elegance of the late monarchy to the epic grandeur of the Napoleonic Empire and the bourgeois society that followed.

He remains best remembered as a supreme master of equine art, whose depictions of horses set a standard for anatomical accuracy and dynamic vitality. His battle paintings provide invaluable visual records of the Napoleonic Wars, rendered with both precision and dramatic flair. Through his genre scenes and caricatures, he offered witty commentary on contemporary life and manners. As an early adopter of lithography, he also played a role in democratizing art distribution. Bridging Neoclassicism and Romanticism, influencing figures like Géricault, and paving the way for later Romantics such as Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Carle Vernet's legacy is that of a versatile, skilled, and historically significant artist who vividly chronicled the spirit and spectacle of his age.