Henry Thomas Alken (1785-1851) stands as one of the most prolific and influential figures in British sporting art during the late Georgian and early Victorian periods. An accomplished painter, etcher, and illustrator, Alken captured the vigour, drama, and often the humour of British country life and sporting pursuits with unparalleled energy and detail. His work provides an invaluable visual record of the era's pastimes, from the thrill of the fox hunt and the racetrack to the quieter moments of angling and shooting. Born into an artistic dynasty, he carved out a unique niche, blending keen observation with a lively, sometimes satirical, style that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to engage audiences today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Henry Thomas Alken was born in Soho, Westminster, London, on October 12, 1785. He was the third son of Samuel Alken, himself a respected sporting artist and etcher, ensuring Henry was immersed in the world of art from a very young age. The Alken family had established a reputation for sporting subjects, and Henry's early training naturally occurred under his father's guidance. This foundational education instilled in him the technical skills and thematic interests that would define his career.

Seeking broader instruction, the young Alken also studied with the miniature painter John Thomas Barber Beaumont (1774-1841). Beaumont, also known as John Barber, was a versatile figure involved in art and social reform. Studying miniature painting likely honed Alken's attention to detail and precision, qualities evident even in his more dynamic and loosely handled sporting scenes. Further formal training was undertaken at the Royal Academy Schools, which he entered in 1796, indicating an early ambition within the established art world.

Despite this formal training, Alken's initial foray into exhibiting was modest. He showed two miniature portraits at the Royal Academy exhibitions early in his career (around 1798 or shortly after). However, portraiture did not prove to be his calling, and these early works did not bring him significant recognition. His true passion and talent lay elsewhere, in the depiction of action, animals, and the British landscape.

In 1809, Alken married Maria Gordon in Ipswich, Suffolk. It is suggested that he may have resided in Ipswich for a period following his marriage, possibly working as an equestrian drawing master. This connection to Suffolk, a county known for its horse racing and rural pursuits, likely further cemented his interest in sporting subjects and provided ample first-hand observation opportunities.

Emergence as a Sporting Artist

Alken's career took a decisive turn towards sporting art around the early 1810s. Initially, he published some of his earliest sporting prints under the pseudonym "Ben Tally Ho," starting around 1812. This playful name, evoking the cries of the hunting field, perfectly suited the energetic and often humorous nature of his early works. This period saw him developing his characteristic style, focusing on capturing the movement and excitement inherent in sports.

By 1816, Alken began publishing works under his own name, signalling a growing confidence and reputation. This marked the beginning of his most productive and defining period. He abandoned any lingering aspirations in miniature painting and dedicated himself almost entirely to the creation of sporting scenes through various media, including oil painting, watercolour, etching, and soft-ground etching, often enhanced with hand-colouring (aquatint).

His output during this time was prodigious. He not only created standalone paintings and prints but also became a highly sought-after illustrator for books and periodicals focused on sport and country life. His ability to convey narrative, character, and atmosphere made his illustrations incredibly popular. He captured the essence of Regency and early Victorian Britain's obsession with outdoor activities and the social rituals surrounding them.

Alken's deep understanding of animal anatomy, particularly horses, was central to his success. He depicted horses not merely as static subjects but as dynamic creatures full of power and grace, whether racing at full gallop, leaping fences, or pulling coaches. This anatomical accuracy, combined with his flair for capturing fleeting moments of action, set his work apart from many contemporaries.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Henry Alken's style is characterized by its dynamism, detail, and often, its infusion of humour. He possessed a remarkable ability to convey speed and movement, making his depictions of hunts and races particularly compelling. His line work, especially in his etchings, is fluid and expressive, capturing the energy of the moment. While capable of detailed rendering, he often prioritized capturing the overall spirit and action of a scene over meticulous finish, particularly in his prints.

He worked proficiently across several mediums. His oil paintings often display a richer palette and more finished appearance, suitable for gallery display. However, it was perhaps in watercolour and printmaking that his unique talents shone brightest. His watercolours possess a lightness and immediacy, effectively capturing changing light and atmospheric conditions.

Alken was a master of etching and aquatint. Many of his most famous works were published as sets of hand-coloured prints. The aquatint process allowed for tonal variations, giving depth and richness to the images, while the hand-colouring added vibrancy. This combination was perfectly suited to the lively subject matter. His skill in composition allowed him to handle complex multi-figure scenes, such as a crowded race meeting or a chaotic moment in the hunting field, with clarity and narrative force.

A distinctive feature of Alken's work is its blend of realism and caricature. While his anatomical understanding of horses and dogs was profound, he often exaggerated postures or facial expressions in both animals and humans to heighten the drama or inject humour. Falls, mishaps, and moments of absurdity were common themes, reflecting a keen observation of the sometimes-comical realities of sporting life. This sets him apart from more purely documentary sporting artists like John Frederick Herring Sr. or the earlier, more classical George Stubbs.

His use of colour was typically bright and clear, enhancing the visual appeal of his prints. The greens of the landscape, the reds of hunting coats, and the varied colours of racing silks are rendered with a vibrancy that brings the scenes to life. Even in potentially chaotic scenes, his compositions remain legible, guiding the viewer's eye through the action.

Major Works and Publications

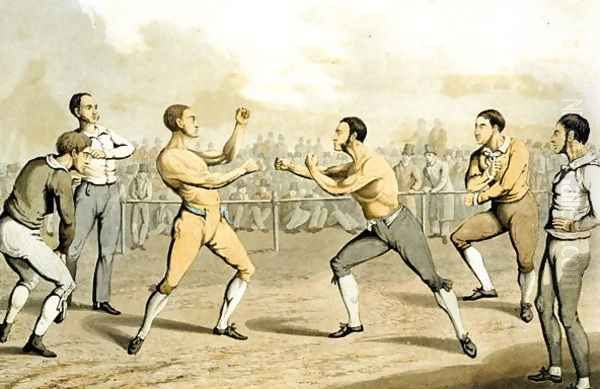

Throughout his prolific career, Henry Alken produced numerous works that became iconic representations of British sporting life. Among his most celebrated achievements is The National Sports of Great Britain, first published in 1821 by Thomas McLean of Haymarket, London. This landmark publication featured fifty hand-coloured aquatint plates illustrating a wide array of sports, including fox-hunting, horse racing, shooting, fishing, boxing, and cockfighting. It remains a seminal work, offering a comprehensive and visually stunning survey of the nation's pastimes during the Regency era. The detailed depictions and lively compositions made it immensely popular and highly collectible.

Another significant publication was A Collection of Sporting and Humorous Designs, which showcased his versatility in capturing both the serious and comical aspects of sport. Similar humorous series included Symptoms of Being Amused (1827) and Humorous Specimens of Popular Songs (published earlier, around 1821-1825), where he illustrated scenes inspired by popular song lyrics, often with a satirical edge. These works highlighted his skill as a social commentator and caricaturist, akin in spirit, if not always in target, to contemporaries like Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank.

Alken's expertise in equine subjects was demonstrated in works like The Beauties and Defects in the Figure of a Horse (1824). This publication, featuring illustrative plates, showcased his deep anatomical knowledge and understanding of horse conformation, valuable information for breeders, owners, and artists alike. It solidified his reputation as an authority on the subject.

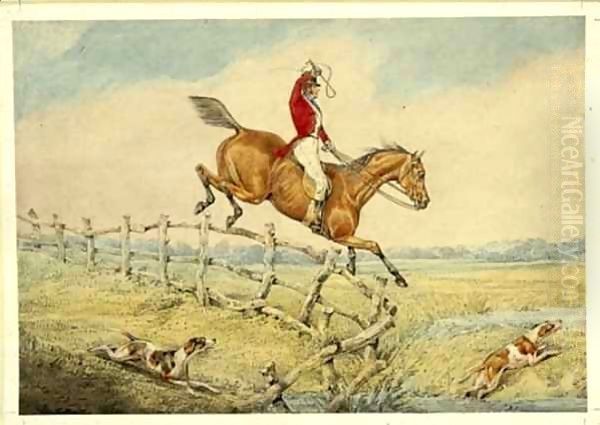

Individual paintings and prints also garnered significant attention. Taking a Fence (versions exist, including one dated 1816 and another 1845) exemplifies his ability to capture the peak moment of action in steeplechasing or hunting, conveying the power of the horse and the skill (or precariousness) of the rider. His series The Night Riders of Nacton (first published March 1, 1839) depicted a famous nocturnal steeplechase and became one of the most successful sporting print series of the time, widely copied and admired for its atmospheric drama.

His satirical inclinations were evident in works like Fashion and Folly. Or the Buck's Pilgrimage, which lampooned the excesses of fashionable society. He also tackled political themes, as seen in prints like Napoleon's Ambition, demonstrating a willingness to engage with broader contemporary issues through his art, often employing caricature to make his point, much like the celebrated political satirist James Gillray.

Alken frequently collaborated with prominent London publishers, most notably Thomas McLean and Rudolph Ackermann. These publishers played a crucial role in disseminating his work through high-quality prints and illustrated books, ensuring his art reached a wide audience across Britain and beyond. His shop in Haymarket, associated with McLean, was a hub for his prolific output during the 1820s.

Themes and Subjects

The core of Henry Alken's oeuvre revolves around British field sports. Fox hunting was a recurring and central theme, depicted in all its stages: the meet, drawing the covert, the chase across country, the checks, the falls, and the kill. He captured the speed, danger, and social dynamics of the hunt with unmatched expertise. His hunting scenes are populated with vividly characterized riders, straining hounds, and powerful horses navigating the challenging terrain of the British countryside.

Horse racing, particularly steeplechasing, was another favourite subject. Alken conveyed the thunderous energy of horses at full stretch, the brightly coloured silks of the jockeys, the crowds of spectators, and the inherent risks of racing over obstacles. Works like The Night Riders of Nacton showcase his ability to create dramatic narratives within these racing scenes.

Beyond hunting and racing, Alken depicted a broad spectrum of outdoor activities. Shooting (game birds like pheasant and grouse), fishing (angling in rivers and streams), coaching (the colourful mail coaches and private carriages that traversed the country's roads), boxing, and even less genteel sports like cockfighting and bull-baiting (reflecting the period's tastes) found their way into his portfolio. The National Sports of Great Britain provides the most comprehensive overview of this thematic range.

While action was paramount, Alken also excelled at capturing the social milieu surrounding these sports. The gatherings at the hunt meet, the crowds at the racecourse, the camaraderie among sportsmen, and the interactions between different social classes are all observed and recorded. His work often contains elements of social commentary, sometimes gently humorous, sometimes more pointedly satirical, regarding the manners, fashions, and follies of the sporting gentry and their associates.

Humour and mishap were constant threads. Alken seemed to delight in depicting the spills and tumbles inevitable in fast-paced sports. Riders falling from horses, anglers getting tangled in their lines, or shooters experiencing embarrassing mishaps add a layer of relatable humanity and amusement to his work. This focus on the less glamorous or more chaotic aspects of sport distinguishes him from artists who presented a more idealized view.

Context and Contemporaries

Henry Thomas Alken operated within a rich tradition of British sporting and animal art. He inherited a legacy from earlier masters like George Stubbs (1724-1806), renowned for his anatomical precision and classical compositions, and Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807), known for his romantic depictions of horses. However, Alken's style was distinctly more dynamic and less formal than these predecessors.

Among his contemporaries specializing in sporting art, several figures stand out. Ben Marshall (1768-1835) was a leading painter of racehorses and sporting portraits, known for a robust, painterly style. John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865) became hugely popular for his detailed and somewhat sentimental depictions of racehorses, farm animals, and coaching scenes. James Pollard (1792-1867) specialized particularly in coaching and racing scenes, capturing the bustling life of the road and track with great accuracy.

The father-and-son duo Dean Wolstenholme Sr. (1757-1837) and Dean Wolstenholme Jr. (1798-1883) were also prominent hunting painters, often working in a detailed narrative style. Alken's own family contributed significantly to the genre, with his father Samuel Alken (c.1756-1815) being an established artist, and two of his sons, Henry Gordon Alken (1810-1894) and Sefferien Alken (1821-1873), following in his footsteps as sporting artists, sometimes leading to confusion in attributions.

In the realm of caricature and social satire, Alken's work shares affinities with giants like Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), James Gillray (1756-1815), and George Cruikshank (1792-1878). While Alken's focus was narrower, primarily on the sporting world, his use of exaggeration and humour to comment on human behaviour places him within this broader graphic satire tradition. His teacher, John Thomas Barber Beaumont, though primarily a miniaturist, was also involved in social commentary through other avenues.

Alken's influence can be seen in the work of later artists and illustrators. Notably, John Leech (1817-1864), the famous Punch cartoonist, admired Alken and was clearly influenced by his style of depicting humorous sporting incidents and equine subjects. Alken's collaborations with publishers like Thomas McLean and Rudolph Ackermann placed him at the heart of the thriving London print market, interacting with a network of engravers, colourists, and fellow artists. Figures like John Crawford might also have been part of his professional circle through these publishing connections.

Later Life and Legacy

Henry Thomas Alken remained remarkably productive throughout the 1820s, 1830s, and into the 1840s. His prints and illustrations continued to be popular, capturing the changing face of British sport and society as the Victorian era dawned. He adapted his style subtly over time but remained true to the energetic and observational approach that had brought him success. His later works, such as the 1845 version of Taking a Hedge, show a continued mastery of dynamic composition and equine form.

Despite the apparent popularity of his work and his prolific output, Alken's later years were marked by financial difficulty. The market for sporting prints, while strong, was competitive, and artists often did not reap the full financial rewards of their creations, with publishers taking a significant share. It is a sad irony that an artist who depicted the leisured pursuits of the wealthy should himself struggle with poverty.

Henry Thomas Alken died in poverty on April 7, 1851, at the age of 66. He left behind an enormous body of work that constitutes one of the most comprehensive visual records of British sporting life in the early nineteenth century. His legacy extends beyond the sheer volume of his output; he defined a particular way of seeing and representing sport – energetic, detailed, often humorous, and deeply engaged with the subject matter.

His influence persisted through his sons, Henry Gordon and Sefferien, who continued the Alken name in sporting art, and through artists like John Leech who adapted his style for humorous illustration. Alken's work captured the spirit of an age, documenting not just the activities themselves but also the associated social customs, dress, and landscapes.

Exhibitions and Collections

Today, Henry Thomas Alken's works are held in numerous prestigious public and private collections worldwide, testament to his enduring importance and appeal. Major institutions housing his paintings, watercolours, and prints include the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which hold significant collections of British prints and drawings.

In the United States, the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, possesses a substantial collection of British sporting art, including important works by Alken such as Hunting Scene (1840) and the 1845 version of Taking a Hedge. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) also includes works by Alken in its collections, occasionally featuring them in exhibitions exploring British art of the period. The Hillstrom Museum of Art at Gustavus Adolphus College, Minnesota, has also exhibited his work, including Taking a Hedge.

His prints, particularly sets like The National Sports of Great Britain, remain highly sought after by collectors of sporting art and rare books. Auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's regularly feature works by Henry Alken, indicating a continued market appreciation for his art. While specific large-scale retrospective exhibitions dedicated solely to Alken may be infrequent, his work is consistently included in broader surveys of British art, sporting art, and printmaking history. These collections and ongoing market interest ensure that Alken's contribution to British art history remains visible and accessible for study and enjoyment.

Conclusion

Henry Thomas Alken was more than just a painter of horses and hounds; he was a vivid chronicler of British life and leisure during a period of significant social change. His vast output, characterized by dynamic energy, meticulous observation, anatomical accuracy, and a frequent dash of humour, captured the essence of sporting pursuits like no other artist of his generation. From the exhilarating chaos of the fox hunt to the technicalities of horse conformation, Alken's work offers a window into the passions and pastimes of Regency and early Victorian Britain. Despite facing financial hardship later in life, his artistic legacy is rich and enduring. As a master of sporting art and a keen observer of the social scene, Henry Thomas Alken holds a unique and important place in the history of British art.