Introduction: A Painter of Refinement

The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands. Amidst giants like Rembrandt and Vermeer, numerous highly skilled painters carved out their own niches, contributing to the rich tapestry of Dutch art. Among these was Caspar Netscher (1639–1684), a painter celebrated for his exquisite portraits and intimate genre scenes. Though perhaps less universally known today than some contemporaries, Netscher achieved considerable fame during his lifetime, admired for his elegant compositions, meticulous technique, and unparalleled ability to render the textures of luxurious fabrics like satin, silk, and oriental carpets. His work provides a fascinating window into the tastes and lives of the Dutch elite in the latter half of the 17th century.

Born into a tumultuous era, Netscher's life and career trajectory reflect both personal resilience and astute adaptation to the evolving art market. Initially trained in the tradition of detailed genre painting, he later became one of the most sought-after portraitists in The Hague, the administrative and diplomatic heart of the Dutch Republic. His style, heavily influenced by his master Gerard ter Borch, evolved towards a refined, almost French-influenced elegance that perfectly captured the aspirations of his clientele. Studying Netscher offers insight not only into his individual talent but also into the broader cultural currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Caspar Netscher's precise birthplace remains uncertain, with historical sources suggesting either Heidelberg, in present-day Germany, or possibly Prague, around the year 1639. His father was Johann Netscher, reportedly a sculptor from Stuttgart. His mother, Elizabeth Vetter, was the daughter of a mayor in Heidelberg, indicating a family of some standing. However, Caspar's early years were marked by the upheaval and tragedy of the Thirty Years' War. It is believed his father died while serving the Polish army, or perhaps during the conflict around Heidelberg.

His widowed mother fled the ravages of war, seeking refuge in the Netherlands. The journey was perilous, and according to early biographers like Arnold Houbraken, Netscher lost two older brothers along the way. The family eventually found safety in Arnhem. Here, the young Caspar was taken under the wing of a wealthy physician and patron of the arts, Dr. Arnold Tulleken (or Artur Nördlein, as mentioned in some sources). Though initially intended for a medical career, Netscher's evident talent and passion for drawing led his guardian to support his artistic inclinations.

His first formal instruction in painting likely came from Hendrik Coster, a local painter primarily known for landscapes and portraits, though relatively obscure today. This initial training provided a foundation, but the most formative period of Netscher's artistic education began when he moved to Deventer around 1654. There, he entered the studio of Gerard ter Borch the Younger, one of the most sophisticated and successful Dutch painters of the era.

The Influence of Gerard ter Borch

Studying with Gerard ter Borch (c. 1617–1681) was a pivotal experience for Netscher. Ter Borch was renowned for his refined genre scenes depicting the quiet, domestic lives of the Dutch upper class, and for his sensitive portraits. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture the subtle textures of materials, particularly the sheen of satin, a skill he passed on to his talented pupil. Netscher worked not just as a student but likely as a valued assistant in Ter Borch's busy studio until about 1658.

Many of Netscher's early works clearly show the imprint of his master's style: small-scale figures, intimate interior settings, meticulous attention to detail, and a particular fondness for rendering luxurious fabrics. Ter Borch's influence is evident in the choice of subject matter – quiet domestic scenes, music lessons, ladies reading letters – as well as in the delicate brushwork and sophisticated colour harmonies. Netscher absorbed these lessons thoroughly, developing a technical prowess that would become a hallmark of his own career. He learned to convey not just the appearance of wealth and refinement, but also a sense of decorum and quiet introspection characteristic of Ter Borch's best work.

Travels, Marriage, and Settling in The Hague

Around 1658 or 1659, Netscher embarked on a journey with the intention of travelling to Italy to further his artistic education, a common ambition for Northern European artists seeking exposure to classical and Renaissance masterpieces. However, his Italian sojourn never materialized. He travelled south, but his journey halted in Bordeaux, France. The reasons for stopping are unclear, but it was here that he met Margaretha Godijn, the daughter of a mathematician and fountain engineer from Liège. They married in Bordeaux in November 1659.

The need to support his new family likely prompted Netscher to focus on painting professionally in Bordeaux for a time. He produced portraits and small genre scenes that found a local market. However, the allure of his homeland, and perhaps the greater opportunities available there, led him to return to the Netherlands. By 1662, Caspar Netscher, along with his wife, settled in The Hague. This move proved decisive for his career. The Hague, as the seat of the government and the residence of the Stadtholder's court, offered significant opportunities for patronage, particularly in the lucrative field of portraiture. That same year, he became a member of the Confrerie Pictura, the city's guild of painters, signalling his establishment as a professional artist in this important centre.

Mastery of Genre Painting

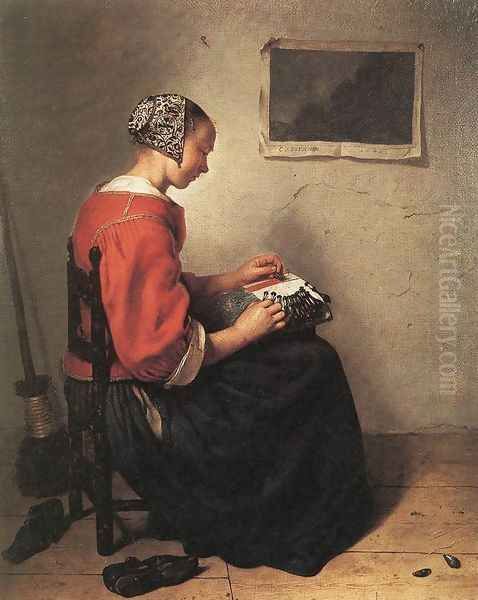

In his early years in The Hague, Netscher continued to produce genre scenes, building upon the foundations laid during his apprenticeship with Ter Borch. These works often depict intimate, dimly lit interiors where well-dressed figures engage in quiet activities: making music, reading or writing letters, tending to children, or engaging in domestic crafts like lacemaking. His style in this period is closely related to the Leiden 'fijnschilders' (fine painters), such as Gerard Dou (1613–1675) and Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635–1681), who were known for their highly detailed, small-scale paintings on panel, often featuring smooth, enamel-like surfaces.

Netscher's genre works stand out for their elegance and psychological nuance. Unlike the often boisterous scenes of Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679), Netscher focused on moments of quiet contemplation or refined social interaction. His figures are typically graceful and poised, inhabiting well-appointed rooms filled with carefully rendered objects – musical instruments, rich draperies, Turkish carpets, and silver vessels. The meticulous depiction of textures, especially the shimmering satin dresses worn by his female figures, became one of his most admired skills, rivaling even that of his master, Ter Borch.

A prime example from this period is The Lace Maker (c. 1662, Wallace Collection, London). This small painting depicts a woman absorbed in her intricate work, seated near a window that provides subtle illumination. The scene exudes tranquility and domestic virtue. Netscher masterfully renders the textures of her clothing, the delicate threads of the lace, and the objects surrounding her, creating a jewel-like composition that invites close inspection. Works like this appealed to the tastes of wealthy Dutch burghers who appreciated depictions of orderly, prosperous domestic life combined with virtuosic technique. Other notable genre painters exploring similar themes of refined interiors included Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667) and Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684), though each had their distinct approach to composition and light.

The Rise as a Fashionable Portraitist

While Netscher continued to paint genre scenes throughout his career, his move to The Hague increasingly steered him towards portraiture. The city's concentration of courtiers, diplomats, and wealthy officials created a strong demand for portraits, and Netscher's refined style was perfectly suited to the task. He quickly gained a reputation as a skilled portrait painter, capable of capturing not only a likeness but also the sitter's status and elegance. His ability to render luxurious clothing and accessories in exquisite detail was particularly valued by his clientele.

His portraits are characterized by their elegance, smooth finish, and often flattering depictions. He typically portrayed his sitters in graceful poses, set against simple dark backgrounds or within subtly suggested interiors or landscapes. The emphasis was often on the richness of their attire – the sheen of silk, the intricate patterns of lace, the soft folds of velvet. This focus on costume and refinement reflected the growing influence of French courtly fashion on Dutch high society in the latter half of the 17th century. Netscher became a leading exponent of this more aristocratic, international style of portraiture in the Netherlands.

His success attracted high-profile commissions. He painted members of prominent Dutch families and figures associated with the court of William III, Prince of Orange, who later became King of England. While perhaps not officially appointed as a court painter, his services were certainly in demand among the circles surrounding the Stadtholder. This patronage cemented his reputation and financial success. His style contrasted with the more psychologically penetrating, often rugged, portraiture of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) from an earlier generation, aligning more closely with the polished elegance favoured by contemporaries like Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) in his later career, or the refined genre-portraits of Jacob Ochtervelt (1634–1682).

Signature Works and Artistic Style

Several works exemplify Netscher's mature style and artistic concerns. The Music Lesson (c. 1665, National Gallery, London) is a superb example of his genre painting, blending technical skill with subtle narrative. It depicts a richly dressed woman playing a cittern while a man listens attentively beside her. The opulent interior, detailed rendering of fabrics (especially the woman's shimmering yellow satin dress), and the theme of music – often associated with harmony and courtship in Dutch painting – are characteristic of Netscher. The composition is balanced, the lighting soft, and the mood intimate.

His portraiture is well represented by numerous examples found in museums worldwide. Works like the Portrait of a Lady with an Orange (c. 1675-1680, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) showcase his ability to combine a sensitive portrayal of the sitter with a dazzling depiction of costume. The lady's silk gown, lace trim, and pearl jewellery are rendered with meticulous care, emphasizing her wealth and social standing. The inclusion of an orange might allude to the House of Orange, suggesting loyalty or connection to the ruling family.

Another charming and popular work is A Boy Blowing Bubbles (c. 1670, National Gallery, London). While seemingly a simple genre scene depicting childhood innocence, bubble-blowing often carried vanitas connotations in Dutch art, reminding viewers of the transience of life and earthly pleasures. Netscher handles the theme with delicacy, capturing the boy's concentration and the ephemeral beauty of the bubble itself. The painting demonstrates his versatility beyond formal portraiture and complex interiors.

Throughout his oeuvre, Netscher maintained a high level of technical finish. His brushwork is typically smooth and controlled, allowing for precise detail without visible strokes. He employed a rich palette, often favouring warm tones and demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of colour harmony. His mastery of light, while perhaps less dramatic than Rembrandt's or as luminously clear as Johannes Vermeer's (1632–1675), effectively models forms and highlights the textures that were central to his art's appeal.

International Recognition and Later Career

By the 1670s, Caspar Netscher was one of the most celebrated and financially successful painters in the Dutch Republic. His reputation extended beyond the Netherlands. According to Houbraken, his fame reached England, and King Charles II invited him to work at the English court. Netscher reportedly declined the invitation, preferring to remain in The Hague where he had a thriving practice and a large family. Whether this invitation actually occurred or is an embellishment to emphasize his status, it reflects the high esteem in which he was held.

His later works continued in the elegant vein he had established, sometimes becoming slightly more formalized, perhaps reflecting the demands of his busy studio and the prevailing international taste for courtly portraiture. He likely employed assistants to help meet the demand for replicas and studio versions of his popular compositions, a common practice at the time. His style influenced younger painters in The Hague and contributed to the shift in Dutch art towards a more decorative, French-influenced aesthetic that would become dominant in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Painters like Godfried Schalcken (1643–1706), another highly polished painter known for candlelight scenes, were contemporaries working within related traditions of fine painting.

Family and Legacy

Caspar Netscher and Margaretha Godijn had a large family, reportedly twelve children, though perhaps only nine survived infancy. Significantly, two of his sons, Constantijn Netscher (1668–1723) and Theodorus Netscher (1661–1728), followed in his footsteps and became accomplished painters themselves. They largely continued their father's style, particularly in portraiture, ensuring the Netscher name remained prominent in Dutch art into the early 18th century. Constantijn worked primarily in The Hague, while Theodorus spent considerable time working successfully in Paris and London. This continuation of an artistic dynasty was relatively uncommon but speaks to the strong foundation Caspar had built.

Caspar Netscher's successful career was cut short by illness. He suffered from gout, a painful condition common at the time, particularly among those who could afford a rich diet. Despite his affliction, he reportedly continued to work diligently until the end. He died in The Hague on January 15, 1684, at the relatively young age of about 45.

His legacy lies in his mastery of elegant representation. He perfectly captured the refined tastes of the Dutch elite in the latter half of the Golden Age. While his work may lack the profound depth of Rembrandt or the enigmatic stillness of Vermeer, Netscher excelled in creating images of sophisticated charm and exquisite detail. His skill in rendering textures, particularly satin, remains remarkable. He successfully bridged the detailed tradition of the Leiden 'fijnschilders' with the growing demand for aristocratic portraiture influenced by international court styles, making him a key figure in the transition of Dutch art towards the aesthetics of the 18th century.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

Caspar Netscher stands as a significant figure in the rich panorama of Dutch Golden Age painting. His journey from a child refugee to one of the most sought-after painters in The Hague is a testament to his talent and adaptability. Through his meticulous genre scenes and elegant portraits, he provided a polished reflection of the world inhabited by the Dutch upper classes. His unparalleled ability to depict the lustre of silk, the softness of velvet, and the intricate patterns of lace and carpets captivated his contemporaries and continues to impress viewers today.

Though sometimes overshadowed by the towering figures of Rembrandt and Vermeer, Netscher's contribution was distinct and highly valued in his time. He represented a particular facet of Dutch art – one characterized by refinement, technical brilliance, and an embrace of worldly elegance. His influence extended through his sons and contributed to the direction of Dutch portraiture after the Golden Age. Caspar Netscher's paintings remain enduringly appealing, offering a glimpse into a world of quiet luxury and sophisticated taste, rendered with consummate skill.