Cecil Charles Windsor Aldin stands as one of the most beloved British artists and illustrators of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Flourishing during the "Golden Age of Illustration," Aldin carved a unique niche for himself with his vibrant, humorous, and affectionate depictions of animals, sporting pursuits, and the enduring charm of the English countryside. His work, characterized by bold lines, expressive characterization, and a deep understanding of his subjects, continues to resonate with audiences today, offering a nostalgic yet lively glimpse into a bygone era.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Slough, Buckinghamshire (now Berkshire), on April 28, 1870, Cecil Aldin was the son of Charles Aldin, a builder, and Sarah Aldin (née Windsor). His artistic inclinations emerged early, nurtured in part by his father, who was himself a keen amateur artist. The young Cecil was reportedly drawing from the age of six, already showing a fascination with the world around him, particularly animals. This early passion would become the defining feature of his long and successful career. His childhood environment, likely filled with the sights and sounds of both town and nearby countryside, provided ample inspiration for his developing eye.

His formal education took place at Eastbourne College and later Solihull Grammar School. These institutions provided a standard Victorian education, but it was clear that Aldin's true calling lay in the arts. His innate talent demanded more specialized training, leading him towards the established art schools of the time. The decision to pursue art professionally was likely supported by his family, recognizing the strength of his burgeoning abilities and the potential for a career in the burgeoning field of illustration, fueled by the era's explosion in printed media.

Formative Education and Influences

Aldin's journey into formal art education began with a period at Albert College. He then sought more focused training in London. He initially enrolled to study anatomy and animal painting under Albert Joseph Moore, a prominent figure associated with the Aesthetic Movement. However, Aldin reportedly found Moore's teaching methods less suited to his temperament and practical goals. He sought a more direct approach to capturing the life and movement of animals, which were rapidly becoming his primary interest.

This led him to the National Art Training School in South Kensington (later renamed the Royal College of Art). Here, he found a more conducive environment. Crucially, he also studied animal painting under William Frank Calderon, a renowned painter and teacher specializing in animal subjects and the founder of his own School of Animal Painting. Calderon's instruction likely provided Aldin with a stronger foundation in animal anatomy and movement, disciplines essential for the convincing portrayal of dogs, horses, and other creatures that would populate his work.

During these formative years, Aldin absorbed the influence of earlier masters of British illustration and caricature. He particularly admired the work of Randolph Caldecott, whose lively line, gentle humor, and charming depictions of rural life set a high standard. John Leech, the great Punch cartoonist known for his sporting scenes and social commentary, was another significant influence, evident in Aldin's later handling of hunting subjects and character types. These artists provided models for combining skillful draughtsmanship with narrative flair and popular appeal.

Launching a Career in Illustration

By the age of 22, Aldin felt ready to establish himself professionally. He moved to the artistic hub of Chelsea in London, taking a studio and beginning the often-precarious life of a freelance artist. The 1890s were a fertile time for illustrators, with numerous magazines and newspapers commissioning artwork to accompany stories, articles, and advertisements. Aldin quickly began to find outlets for his talent.

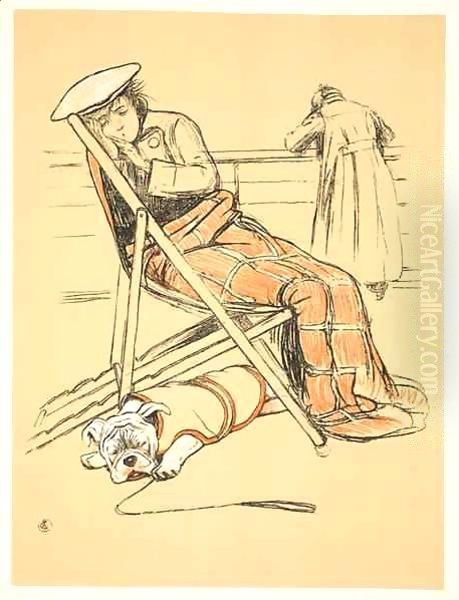

His work started appearing in prominent publications like The Illustrated London News, The Sketch, The Graphic, and the humorous magazine Punch. These commissions provided not only income but also invaluable exposure, bringing his distinctive style to a wide audience. His ability to capture character, movement, and humor made his illustrations stand out. He depicted scenes of London life, social events, and, increasingly, the animal subjects that would become his trademark. This period was crucial for honing his craft, meeting deadlines, and building relationships with editors and publishers.

His early success was built on versatility and a strong work ethic. He tackled diverse subjects, demonstrating his adaptability. However, his affinity for animals, particularly dogs and horses, soon became apparent to commissioners and the public alike. This specialization, combined with his accessible and engaging style, laid the groundwork for his enduring popularity and the major commissions that would follow.

The Illustrator's Craft: Books and Periodicals

Cecil Aldin's reputation grew significantly through his extensive work as a book illustrator. He brought his characteristic energy and charm to numerous classic and contemporary texts. One of his most notable early commissions was illustrating Rudyard Kipling's The Second Jungle Book, specifically contributing powerful images for stories like "Letting in the Jungle" and "Red Dog." While not illustrating the first Jungle Book, his work for Kipling demonstrated his ability to handle dramatic animal narratives.

He produced memorable illustrations for editions of Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, capturing the novel's episodic nature and eccentric characters with gusto. His affinity for animals shone through in his illustrations for Anna Sewell's beloved classic Black Beauty, where he conveyed the equine protagonist's experiences with empathy and anatomical accuracy. He also illustrated Maurice Maeterlinck's My Dog, showcasing his talent for portraying canine personality.

Beyond these highlights, Aldin illustrated dozens of other books, ranging from children's stories and sporting tales to guides and his own authored works. His illustrations were not mere decorations; they actively interpreted the text, adding layers of humor, character, and atmosphere. His work for periodicals continued throughout his career, maintaining his public profile. His long association with The Illustrated London News was particularly significant, providing a regular platform for his art.

Master of Animals: Dogs and Horses

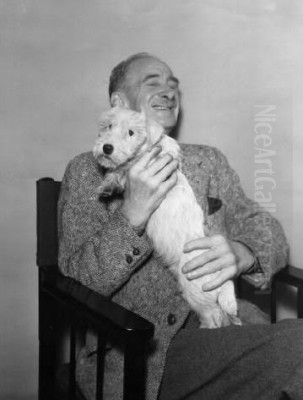

While a versatile artist, Cecil Aldin is arguably best remembered for his depictions of animals, especially dogs and horses. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture not just their physical likeness but also their individual personalities, moods, and characteristic movements. This stemmed from a deep affection for animals and close observation, honed through years of study and living alongside them.

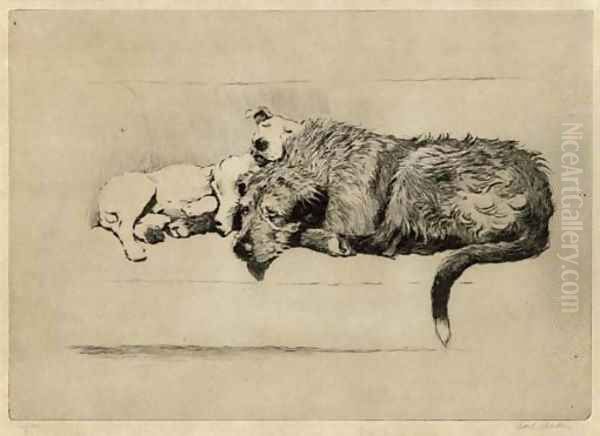

Dogs were a particular passion. Aldin owned many throughout his life, and they frequently served as his models. His most famous canine companions included Cracker, a bull terrier with a mischievous glint in his eye, and Micky, a dignified Irish wolfhound. These dogs, along with various terriers, hounds, and spaniels, appeared repeatedly in his prints, illustrations, and paintings. Works like Sleeping Partners, depicting two slumbering terriers, or the portfolio A Dozen Dogs or So, showcase his intimate understanding of canine behaviour and his humorous take on their antics. He avoided overly sentimentalizing his subjects, instead focusing on their inherent character and vitality.

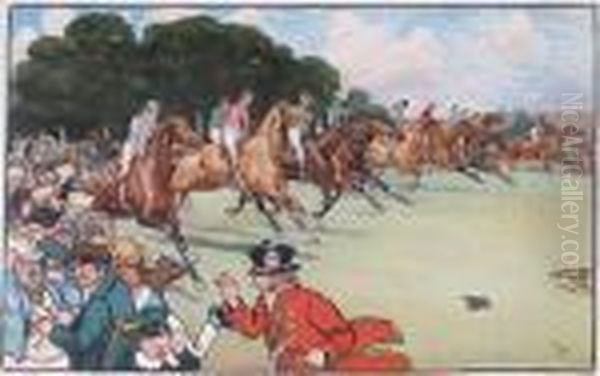

Horses were equally central to his art, particularly in the context of hunting and racing. He depicted them with anatomical correctness but also with a sense of energy and spirit. Whether showing hunters clearing fences, racehorses thundering down the track, or sturdy coaching horses pulling their load, Aldin conveyed their power and grace. His understanding of equine movement was exceptional, likely enhanced by his own experiences as a rider. Compared to contemporaries like the more detailed Lionel Edwards or the impressionistic 'Snaffles' (Charles Johnson Payne), Aldin's horses often possess a robust, slightly stylized quality that emphasizes their strength and character within the narrative of the scene.

The Sporting Life: Hunting and Racing

Cecil Aldin was not merely an observer of the sporting world; he was an active participant. He was a passionate sportsman, particularly devoted to foxhunting. For many years, he served as the Master of the South Berkshire Hunt, a prestigious position that placed him at the heart of the hunting community. This firsthand experience infused his sporting art with authenticity and understanding.

His hunting scenes are among his most iconic works. Series like The Fallowfield Hunt prints capture the excitement, camaraderie, and occasional mishaps of a day's hunting with characteristic humor and dynamism. He depicted the full panorama of the hunt: the gathering at the meet, the hounds working a scent, the thrill of the chase across country, and the weary return home. His portrayals often included recognizable character types – the seasoned Master, the eager novice, the sturdy farmer – adding a layer of social observation. These prints were immensely popular, decorating the walls of country houses and sporting clubs throughout Britain.

Aldin also turned his attention to the world of horse racing, capturing the colour and spectacle of events like the Grand National. Prints such as The Bluemarket Races convey the bustling energy of a country race meeting. While perhaps less prolific in racing scenes compared to hunting, his work in this genre still demonstrates his skill in depicting equine speed and the vibrant atmosphere of the turf. His sporting art provides a valuable visual record of these traditional aspects of British rural life during the Edwardian era and beyond.

A Painter of Inns and Rural Charm

Beyond the dynamic world of sport and animals, Cecil Aldin possessed a deep appreciation for the quieter charms of the English countryside and its vernacular architecture. He produced numerous works depicting picturesque villages, thatched cottages, and, most notably, historic coaching inns. These subjects allowed him to explore themes of history, tradition, and the enduring beauty of rural England.

His series of prints and illustrations featuring old inns became particularly well-known. Titles like The Bell Inn at Stilton or The George Inn, Dorchester capture the unique character and inviting atmosphere of these historic establishments. He often depicted them with coaches arriving or departing, hinting at the bustling life they once supported in the pre-railway era. Aldin rendered the textures of old timber, weathered brick, and stone with affection, emphasizing the buildings' picturesque qualities and their integration into the surrounding landscape.

These works reveal a more contemplative side of Aldin's art. While still employing his characteristic bold lines and often incorporating figures and animals, the focus shifts towards atmosphere and architectural character. They evoke a sense of nostalgia for a slower pace of life and celebrate the architectural heritage of the English countryside. This aspect of his work further broadened his appeal, attracting those charmed by rural scenery and historic buildings as well as animal and sporting enthusiasts.

Style and Technique

Cecil Aldin developed a highly recognizable artistic style marked by its energy, clarity, and humor. His primary medium was often watercolour, frequently combined with a strong, fluid ink line or charcoal/pastel outlines. This technique allowed for both precise definition of form and expressive rendering of colour and texture. He favoured clear, often bright colours, applied in broad washes, which contributed to the vibrancy and immediacy of his work.

A key characteristic of his style is the bold, confident line work. Whether defining the contours of a dog, the musculature of a horse, or the timbers of an old inn, his lines are economical yet highly descriptive. They convey movement and character with remarkable efficiency. He often simplified backgrounds, focusing attention on the main subjects and action, which enhanced the narrative impact of his illustrations and prints.

Aldin was also proficient in printmaking techniques, including etching and lithography. His etchings, particularly of hunting scenes, demonstrate a finer, more detailed approach while retaining his characteristic liveliness. His lithographs, often used for posters and larger prints, allowed for bold compositions and flat areas of colour, reflecting the influence of contemporary poster artists like the Beggarstaff Brothers (William Nicholson and James Pryde) and Dudley Hardy. Across all media, his work is unified by its accessibility, its focus on character and narrative, and its underlying warmth and good humor. He avoided the intricate detail of contemporaries like Arthur Rackham or the ethereal fantasy of Edmund Dulac, favouring instead a robust, down-to-earth style perfectly suited to his chosen subjects.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Cecil Aldin was an active figure in the London art scene and maintained friendships and professional relationships with many fellow artists. He was a key figure in the formation of the London Sketch Club in 1898, a social and working group for illustrators and designers. Fellow founding members included prominent artists like Phil May, John Hassall, Lance Thackeray, Tom Browne, and Dudley Hardy. The club provided a venue for camaraderie, mutual support, and collaborative sketching sessions, fostering a vibrant creative environment.

His influences, as mentioned, included Randolph Caldecott and John Leech. He worked alongside contemporaries who specialized in similar fields, such as the sporting artists Lionel Edwards and 'Snaffles' (Charles Johnson Payne). While potentially competitors in the market for sporting prints, there was often mutual respect among artists working within the same genre. His book illustration work placed him within the broader context of the Golden Age of Illustration, alongside figures like Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, and Beatrix Potter, though his style remained distinct from theirs.

He also collaborated indirectly with writers like Rudyard Kipling and Charles Dickens by illustrating their works. His professional life involved interactions with publishers, printers, and gallerists. He even referenced works by other artists, such as Anna Lea Merritt, indicating an awareness of the wider art world. His engagement with contemporaries, through clubs, collaborations, and the general artistic milieu of London, enriched his career and situated him firmly within the artistic currents of his time.

Personal Life and Passions

In 1895, Cecil Aldin married Margaret Dorothy Morris, the daughter of a local furrier. The couple had two children, a daughter, Gwendoline, and a son, Dudley. Aldin was devoted to his family and enjoyed a life that balanced his professional commitments with his love for the countryside and outdoor pursuits. The family lived in various locations, often choosing homes that allowed Aldin easy access to hunting and riding.

His passion for animals extended beyond his art. He was a genuine dog lover, and his home was rarely without several canine companions. His enthusiasm for hunting was equally sincere, forming a major part of his social life and providing endless subject matter for his work. He embraced the role of Master of the South Berkshire Hunt with dedication.

The First World War brought profound personal tragedy. His son, Dudley, was killed in action in 1917 while serving with the Royal Artillery. This loss deeply affected Aldin. He himself served during the war, initially as a Remount Purchasing Officer, responsible for acquiring horses for the army – a role that utilized his extensive equine knowledge. Later in life, Aldin developed severe arthritis, which tragically curtailed his ability to ride and hunt. This, combined with the lingering grief over his son's death and perhaps a desire for a warmer climate, led him and his wife to move to Majorca, Spain, in the early 1930s. Despite these challenges, he continued to draw and paint. He also demonstrated a commitment to animal welfare, supporting organizations like the Blue Cross.

Recognition and Legacy

Cecil Aldin achieved considerable fame and success during his lifetime. His prints and illustrations were immensely popular, adorning homes, pubs, and clubs across Britain and beyond. He was elected a member of the prestigious Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) in 1908, a formal recognition of his standing in the art world. His work was widely exhibited, and he authored and illustrated several books himself, including his autobiography, Time I Was Dead (1934).

His legacy endures primarily through his distinctive and appealing artwork. He captured a specific vision of English life – energetic, humorous, and deeply connected to animals and the countryside – that continues to hold nostalgic appeal. His illustrations are considered prime examples of the Golden Age of British Illustration, noted for their technical skill and narrative power. His depictions of dogs, in particular, remain iconic, capturing the essence of various breeds with unmatched charm and insight.

Today, Aldin's original works, prints, and illustrated books are highly sought after by collectors. His art is held in numerous public and private collections, including the Yale Center for British Art. He influenced subsequent generations of animal artists and illustrators. More broadly, his work serves as a vivid social document, reflecting the pastimes, aesthetics, and social nuances of the Edwardian era and the interwar years. He remains celebrated for his ability to bring joy, humor, and a sense of vibrant life to his art. Cecil Aldin passed away in London on January 6, 1935, leaving behind a rich body of work that continues to delight and engage.

Conclusion

Cecil Aldin's contribution to British art lies in his unique ability to blend skilled draughtsmanship with infectious humor and a profound empathy for his subjects. Whether depicting the thrill of the chase, the quirky personality of a terrier, or the timeless appeal of a country inn, his work is infused with vitality and warmth. He captured the spirit of English country life in a way that was both authentic and highly engaging, earning him a lasting place in the hearts of the public and the annals of illustration history. His legacy is not just in the images he created, but in the enduring affection they inspire, reminding us of the simple pleasures found in the company of animals and the beauty of the natural world.