Charles Branwhite (1817-1880) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. A native of Bristol, a city with its own burgeoning artistic identity during his formative years, Branwhite carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a painter of landscapes, with a particular and enduring fascination for the stark beauty and atmospheric subtleties of winter. Working proficiently in both watercolour and oils, he captured the essence of the British countryside, often under a mantle of snow or the crisp light of a frosty day. His journey from a sculptor's apprentice to a respected member of the prestigious Old Watercolour Society is a testament to his dedication and evolving artistic vision, deeply rooted in the observational traditions of his era yet touched by a personal sensitivity to the natural world.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Bristol

Born in Bristol in 1817, Charles Branwhite was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. His father, Nathan Cooper Branwhite (1775-1857), was himself an accomplished artist, known for his miniature portraits and watercolour paintings, as well as being a figure engraver. This familial connection to the arts undoubtedly provided an early stimulus for young Charles. Initially, however, his artistic inclinations were channelled towards three-dimensional forms. He received his foundational training in sculpture under his father's tutelage, a discipline that would have instilled in him a keen sense of form, structure, and the play of light on surfaces – skills that would later translate effectively into his two-dimensional work.

Bristol, during the early to mid-19th century, was a vibrant hub of artistic activity, fostering what became known as the Bristol School of artists. This loose collective, which included figures like Francis Danby, Samuel Jackson, and James Johnson, was characterized by a romantic and often poetic approach to landscape, often imbued with a unique atmospheric quality. Though Charles Branwhite's primary period of activity came slightly after the main flourishing of the early Bristol School, the city's artistic legacy and the presence of influential figures would have contributed to the environment in which he developed. His eventual shift from sculpture to painting, particularly to watercolour, marked a pivotal decision in his career, aligning him with a medium that was experiencing a golden age in Britain.

The Pivotal Influence of William James Müller

A crucial figure in Charles Branwhite's artistic development was William James Müller (1812-1845). Müller, also Bristol-born and a leading light of the later Bristol School, was a painter of prodigious talent, known for his vigorous brushwork, experimental use of colour, and his ability to capture dramatic atmospheric effects. Branwhite became a pupil of Müller, and the impact of this mentorship is evident in his subsequent work. Müller was an advocate of direct observation from nature, a practice that was gaining increasing importance, championed by thinkers like John Ruskin. He was also known for his bold, expressive style, which contrasted with some of the more meticulously detailed approaches of other contemporaries.

From Müller, Branwhite likely absorbed a more dynamic approach to composition and a greater confidence in handling paint, whether watercolour or oil. Müller's own travels, particularly to the Near East, brought an exotic and vibrant palette to British art, but his British landscapes also possessed a remarkable freshness and energy. This emphasis on capturing the immediate sensation of a scene, the transient effects of light and weather, would have resonated with Branwhite, particularly as he began to specialize in the challenging subject of winter landscapes, where such effects are paramount. The legacy of Müller, though his own life was tragically short, lived on through pupils like Branwhite, who adapted these lessons to their own artistic temperaments.

Artistic Style: Realism, Winter, and the Mastery of Watercolour

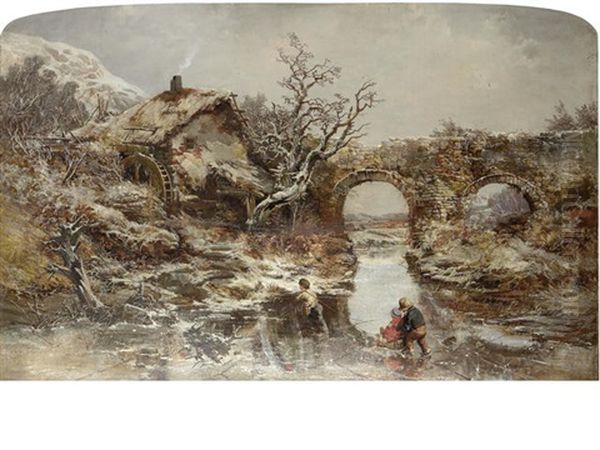

Charles Branwhite's mature artistic style is characterized by a strong vein of realism, particularly in his depiction of the natural world. He was not an artist given to overt romanticism in the vein of early J.M.W. Turner or the sublime drama of John Martin. Instead, his work focused on the tangible, observable aspects of the British countryside. His particular forte became the winter scene. These were not merely picturesque views but often evocative portrayals of the season's specific character: the crispness of frost, the reflective qualities of ice, the muted colours of a snow-laden landscape, and the long shadows cast by a low winter sun.

His paintings often feature figures, not as primary subjects in a narrative sense, but as integral parts of the landscape, perhaps engaged in rural labour or navigating the wintry conditions. This adds a human element and a sense of scale to his compositions. Works such as "A Frozen Stream," "Winter Landscape with Skaters," or "The Old Mill in Winter" (descriptive titles for typical subjects) exemplify his focus. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to render the textures of snow and ice, the bare branches of trees, and the often-subtle gradations of light and colour found in winter. His use of rich, yet controlled, colour allowed him to convey the coldness of the season without sacrificing visual interest, often finding warmth in the hues of a winter sunset or the earthy tones peeking through the snow.

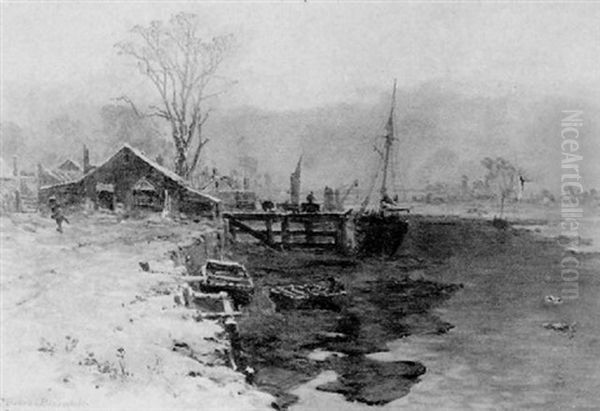

While proficient in oils, Branwhite gained particular recognition as a watercolourist. The 19th century saw watercolour painting elevate from a preparatory medium to a highly respected art form in its own right, thanks to artists like Thomas Girtin, J.M.W. Turner, David Cox, and Peter De Wint. Branwhite contributed to this tradition with his skilled handling of the medium. His watercolours show a fine balance between detailed observation and broad, atmospheric washes, capturing the delicate translucency of ice or the soft diffusion of light in a winter sky.

The Old Watercolour Society and Professional Acclaim

A significant milestone in Charles Branwhite's career was his association with the Society of Painters in Water Colours, often referred to as the Old Watercolour Society (OWS). Founded in 1804, the OWS was the premier institution for watercolour artists in Britain, and election to its ranks was a mark of considerable professional achievement. Its annual exhibitions were major events in the London art calendar, attracting critics and collectors alike. Artists such as Copley Fielding, David Cox, and later Myles Birket Foster and Helen Allingham were prominent members.

Branwhite was elected an Associate of the OWS in 1849 and became a full Member in the same year, a relatively swift progression that indicates the high regard in which his work was held by his peers. This membership provided him with a prestigious platform to exhibit his work regularly to a discerning audience. It also placed him firmly within the mainstream of British watercolour practice, contributing to the ongoing development and appreciation of the medium. His consistent contributions to the OWS exhibitions helped solidify his reputation as a leading painter of winter landscapes.

Exhibitions, Themes, and Artistic Reach

Throughout his career, Charles Branwhite was a regular exhibitor at various London institutions. Besides the Old Watercolour Society, his works were shown at the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists at Suffolk Street. His paintings, often depicting scenes from his native West Country but also from Wales and other parts of Britain, found favour with the Victorian public, who appreciated the familiar charm and skillful rendering of his landscapes.

His thematic range, while centered on landscapes, was not exclusively confined to winter. He also painted scenes of picturesque rivers, rural architecture such as windmills and cottages, and coastal views. These subjects were popular in the Victorian era, reflecting a nostalgia for the countryside and an appreciation for the picturesque. His works often included carefully observed details of rural life, with figures and animals integrated naturally into their settings.

There is some indication that Branwhite's artistic horizons extended beyond Britain, with mentions of him exhibiting in Switzerland and Italy, and even residing in Rome for a period. Such continental travel was common for British artists, offering new subjects and exposure to different artistic traditions. If he did spend time in Italy, it would have exposed him to a different quality of light and landscape, which could have subtly informed his work, even if his primary focus remained British scenery. The great J.M.W. Turner, for instance, found immense inspiration in Italian light and landscape, which transformed his palette.

The Context of the Bristol School and Contemporaries

Charles Branwhite's artistic journey is best understood within the context of the Bristol School and the broader trends in Victorian landscape painting. The Bristol School, in its initial phase (roughly 1810s-1830s), included artists like Francis Danby, Edward Villiers Rippingille, Samuel Jackson, and James Johnson. These artists were known for their poetic, often moonlit or twilight scenes, and a shared practice of sketching outdoors around Bristol's scenic environs, such as Leigh Woods and the Avon Gorge. Nathan Cooper Branwhite, Charles's father, was also associated with this group.

While Charles Branwhite's style was perhaps more grounded in direct realism than the sometimes visionary romanticism of the early Bristol School figures like Danby, he inherited their deep connection to the local landscape. William James Müller, his teacher, acted as a bridge figure, combining the atmospheric concerns of the Bristol School with a more robust, painterly technique influenced by 17th-century Dutch landscape painters and contemporary British artists like John Constable. Constable's emphasis on capturing the "chiaroscuro of nature" and his detailed studies of weather phenomena had a profound impact on British landscape painting.

Other contemporaries whose work provides a backdrop to Branwhite's include the aforementioned watercolour masters like David Cox and Peter De Wint, known for their broad, expressive handling of the medium. Samuel Palmer, with his intensely personal and spiritual visions of the Shoreham countryside, represented a more mystical strand of Romanticism. Later in Branwhite's career, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with their emphasis on truth to nature and meticulous detail (though in a different stylistic vein), also made a significant impact on the Victorian art world. Figures like John Brett, a Pre-Raphaelite associate, produced landscapes of incredible precision. While Branwhite did not adopt Pre-Raphaelite intensity, the general Victorian appreciation for detailed observation of nature would have supported his realistic approach.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Charles Branwhite's work might be elusive, several paintings and their typical characteristics can be highlighted. His winter scenes are, of course, paramount. Titles like "A Hard Frost," "Winter Sunset, with figures and felled timber," "Frozen Out," and "On the Avon, near Bristol, after a heavy snowstorm" are indicative of his preferred subjects.

In "A Hard Frost," one might expect to see the crisp, sharp light of a freezing day, with intricate renderings of hoarfrost on trees and grasses. The figures might be shown huddled against the cold or engaged in necessary winter tasks. "Winter Sunset" would likely showcase his skill in capturing the fleeting, often dramatic colours of the sky as the sun dips below the horizon, its light reflecting off snow and ice, creating a scene of both beauty and melancholy. The inclusion of "felled timber" points to his interest in depicting human interaction with the landscape, even in its harsher aspects.

"Frozen Out" suggests a narrative element, perhaps depicting animals or people struggling with the privations of a severe winter. Such scenes resonated with Victorian sensibilities, which often appreciated art that combined picturesque beauty with a touch of social observation or sentiment. His views "On the Avon, near Bristol" demonstrate his connection to his local scenery, capturing the familiar river under the transformative cloak of winter. These works would showcase his ability to handle complex reflections on icy water and the textures of snow-covered riverbanks. His paintings often featured a strong sense of atmosphere, whether the still, biting air of a frost or the soft, diffused light of a snowy day.

Later Career, Legacy, and Enduring Appeal

Charles Branwhite continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, remaining a respected figure in the British art world until his death in Bristol in 1880. He maintained his connection with the Old Watercolour Society and his commitment to landscape painting. His dedication to the theme of winter, in particular, set him apart. While many artists painted occasional winter scenes, Branwhite made it a recurring and central part of his oeuvre, exploring its myriad moods and effects with consistent skill and sensitivity.

The legacy of Charles Branwhite lies in his contribution to the tradition of British landscape painting, particularly in watercolour. He was an artist who, while not a radical innovator in the mould of Turner, excelled in his chosen field, producing works of quiet beauty and technical accomplishment. His paintings offer a valuable record of the Victorian perception of the British countryside and demonstrate the enduring appeal of winter as an artistic subject. His work would have been familiar to a generation of Victorian art lovers and would have influenced younger landscape painters who admired his technical skill and his ability to capture the specific character of a place and season.

Unfortunately, as mentioned in some accounts, a portion of his work may have been lost during the Second World War, possibly in the bombing raids that affected Bristol. This makes the surviving examples of his art all the more important for appreciating his contribution. Today, his paintings can be found in various public and private collections, and they continue to appear at auction, admired for their skillful execution and their evocative portrayal of a bygone era of the British landscape. He remains a testament to the depth of talent found within the regional art scenes of Victorian Britain and a fine exponent of the art of watercolour.

Conclusion: An Artist of Substance and Sensitivity

Charles Branwhite was an artist of considerable substance and sensitivity, whose career reflects the artistic currents of his time while also showcasing a distinct personal vision. From his early training in sculpture to his mastery of watercolour and oil in depicting the nuanced landscapes of Britain, particularly its winters, he demonstrated a consistent dedication to his craft. Influenced by his father, Nathan Cooper Branwhite, and significantly by his teacher, William James Müller, he absorbed the lessons of the Bristol School and the broader traditions of British landscape painting, forging a style marked by realism, atmospheric depth, and a keen eye for the effects of light and weather.

His membership in the Old Watercolour Society and his regular exhibitions at prestigious London venues attest to the respect he garnered among his peers and the public. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries like Turner or Constable, or later figures who captured the public imagination like Myles Birket Foster, Charles Branwhite's contribution is significant. He excelled in capturing the often-challenging beauty of winter, transforming snow, ice, and frost into subjects of compelling artistic interest. His work provides a lasting window onto the Victorian landscape and stands as a fine example of the skill and dedication that characterized the best of British 19th-century painting. His art continues to be appreciated for its technical proficiency, its honest portrayal of nature, and its quiet, enduring charm.