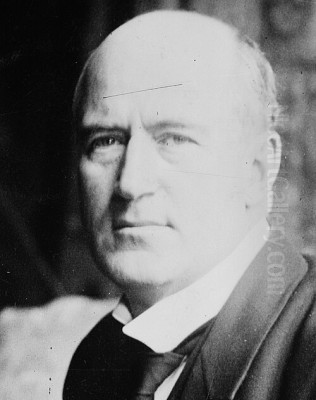

Charles Dana Gibson stands as a towering figure in the history of American illustration, an artist whose pen and ink drawings not only captured the zeitgeist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries but also actively shaped its social and aesthetic ideals. Born on September 14, 1867, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and passing away on December 23, 1944, in New York City, Gibson's legacy is inextricably linked with his most famous creation, the "Gibson Girl." This iconic image of the modern American woman became a cultural phenomenon, influencing fashion, social mores, and the very perception of femininity for a generation. His work, characterized by its elegant line work, subtle wit, and keen observation of society, established him as a master of graphic art and a significant commentator on American life.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Charles Dana Gibson's artistic inclinations were apparent from a young age. Growing up in a cultured New England family, he was encouraged to pursue his talents. His formal artistic training began at the prestigious Art Students League in New York City, a crucible for many aspiring American artists. Here, he honed his skills under the tutelage of established figures, absorbing the academic traditions while developing his unique graphic style. Instructors like Thomas Eakins, though perhaps not directly teaching Gibson, had a profound impact on the League's ethos, emphasizing anatomical accuracy and direct observation, principles that would subtly inform Gibson's later work.

To further broaden his artistic horizons, Gibson, like many ambitious American artists of his time, traveled to Paris. The French capital was then the undisputed center of the art world, and studying there, even briefly, was a rite of passage. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, exposing himself to European artistic currents and refining his draughtsmanship. This period abroad, though not resulting in a wholesale adoption of European avant-garde styles, undoubtedly enriched his visual vocabulary and technical proficiency, preparing him for the demanding world of professional illustration back in the United States. He was a contemporary of artists like John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, American expatriates who found fame in Europe, though Gibson's path would lead him to define American popular visual culture from within.

The Ascent in Illustration and Life Magazine

Upon returning to the United States, Gibson embarked on his professional career. The late 19th century was a burgeoning period for illustrated magazines, and artists found ample opportunities to showcase their work. Gibson began submitting his drawings to various publications. His breakthrough came with his association with Life, a humor and general interest magazine founded in 1883 (not to be confused with the later pictorial magazine of the same name). His illustrations quickly became a staple of the magazine, their sophistication and charm resonating with a wide audience.

Gibson's early work for Life and other periodicals like Harper's Weekly, Scribner's Magazine, and The Century Magazine demonstrated his evolving style. He moved away from the more detailed, cross-hatched techniques common among earlier illustrators towards a bolder, more fluid line. His compositions were elegant, his figures imbued with personality, and his social satire, though gentle, was pointed. He was part of a "Golden Age of American Illustration," a period that also saw the rise of talents such as Howard Pyle, known for his historical and adventure illustrations, and his many successful students like N.C. Wyeth and Maxfield Parrish. Gibson's distinct approach, however, carved out a unique niche for him.

The Birth of the Gibson Girl

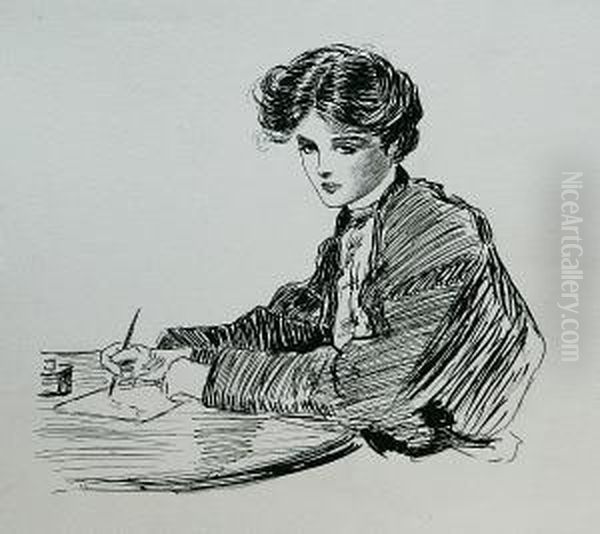

It was in the pages of Life and other magazines in the 1890s that the "Gibson Girl" began to emerge. This idealized image of the young American woman was an amalgam of observations, but it is widely acknowledged that Gibson's primary muse was his wife, Irene Langhorne, whom he married in 1895. Irene, one of the famously beautiful Langhorne sisters of Virginia (another of whom, Nancy, would become Lady Astor, the first woman to sit as a Member of Parliament in the British House of Commons), embodied the grace, independence, and spirit that characterized the Gibson Girl. Her sisters also served as models, contributing to the composite ideal.

The Gibson Girl was not merely a pretty face; she was a cultural statement. Tall and slender, with an S-shaped corseted figure, a cascade of upswept hair (often in a pompadour or chignon), and a confident, intelligent gaze, she represented a new type of woman. She was athletic, often depicted cycling, playing golf, or engaging in other outdoor activities. She was educated, poised, and capable of witty repartee, often shown outmaneuvering her male admirers. The Gibson Girl was independent but not radical, fashionable but not frivolous. She was the personification of an American ideal, a counterpart to the burgeoning nation's sense of optimism and self-assurance. Her image was a stark contrast to the more demure Victorian ideals of womanhood that preceded her.

Characteristics and Artistic Style of the Gibson Girl

Gibson's artistic rendering of this iconic figure was masterful. He primarily worked in pen and ink, creating striking black and white images. His line was confident and expressive, capable of conveying both delicate beauty and strong character with remarkable economy. He had an exceptional ability to suggest form and texture through line weight and placement, often utilizing negative space to great effect. The Gibson Girl's elaborate hairstyles, fashionable attire (shirtwaists, long skirts, feathered hats), and graceful postures were all meticulously rendered, yet never appeared stiff or overworked.

His compositions were often dynamic, capturing moments of social interaction, quiet contemplation, or playful activity. While the Gibson Girl was undoubtedly idealized, Gibson imbued her with a sense of personality and intelligence. He often placed her in narrative situations, creating visual short stories that commented on courtship, marriage, and societal expectations. His work displayed a keen understanding of human psychology and social dynamics, often with a touch of gentle satire. This narrative quality, combined with the aesthetic appeal of the Gibson Girl, made his drawings immensely popular. His style influenced a generation of illustrators, including James Montgomery Flagg, who, while famous for his "I Want YOU" Uncle Sam poster, also created his own popular female archetypes.

The Cultural Impact of the Gibson Girl

The Gibson Girl transcended the pages of magazines to become a true cultural phenomenon. Her image was ubiquitous. She adorned not only magazine covers and illustrations but also a vast array of commercial products, from wallpaper and pillowcases to teacups and souvenir spoons. Women across America emulated her hairstyle, her fashion, and her confident demeanor. The "Gibson Girl look" became the aspirational standard of beauty and style for nearly two decades, from the 1890s through the First World War.

Her influence extended beyond mere aesthetics. The Gibson Girl represented a step towards female emancipation. While not a suffragette in the overt political sense, her independence, her engagement in sports, and her implied intelligence challenged traditional gender roles. She was seen as an equal to men, capable of engaging with them on her own terms. This portrayal contributed to a broader societal shift in perceptions of women's capabilities and their place in society. She was, in many ways, the visual embodiment of the "New Woman" emerging at the turn of the century. Artists like Elizabeth Shippen Green and Violet Oakley, successful female illustrators and part of Howard Pyle's circle, were real-life examples of the capable, professional women that the Gibson Girl archetype seemed to champion.

Gibson's Broader Oeuvre and Social Commentary

While the Gibson Girl was his most famous creation, Charles Dana Gibson's artistic output was diverse. He produced numerous series of drawings that offered witty and insightful commentary on American society, particularly its upper echelons. Series like "The Education of Mr. Pipp," which chronicled the humorous European adventures of a self-made American millionaire and his socially ambitious family, and "A Widow and Her Friends," which explored the social life of an attractive and eligible widow, were immensely popular.

These works showcased Gibson's talent for character development and social satire. He gently poked fun at the pretensions of the nouveau riche, the complexities of courtship, the dynamics of marriage, and the foibles of human nature. His humor was rarely biting, more often observational and sympathetic. He captured the nuances of social etiquette, the unspoken rules of high society, and the changing landscape of American life. His drawings provide a valuable visual record of the manners, fashions, and preoccupations of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. In this, his work shares a certain observational acuity with contemporary writers like Edith Wharton or Henry James, who explored similar social milieus in their novels. His ability to capture social types was akin to that of British illustrators like George du Maurier, whose work for Punch also satirized society, and whom Gibson admired.

Technical Mastery and Influence on Illustration

Gibson's technical skill was widely admired. His mastery of pen and ink was unparalleled. He could create a sense of volume and depth with seemingly effortless strokes. His understanding of anatomy and drapery was evident in the graceful rendering of his figures. The clarity and elegance of his line work made his drawings highly reproducible, a crucial factor in the age of mass-circulation magazines. He was a master of composition, arranging figures and elements within the frame to create visually engaging and narratively compelling images.

His style had a profound impact on other illustrators. Many artists attempted to emulate his clean lines and sophisticated portrayals of modern life. The "Gibson look" became a desirable aesthetic, and his influence can be seen in the work of contemporaries and successors. Artists like J.C. Leyendecker, famous for his Arrow Collar Man and Saturday Evening Post covers, while possessing his own distinct and powerful style, operated within a similar realm of idealized American archetypes and sophisticated graphic design. Gibson's success elevated the status of illustration as an art form, demonstrating its power to shape popular culture and reflect national identity. He was also a contemporary of artists working in different veins, such as Frederic Remington, who captured the American West, or Winslow Homer, whose earlier work included powerful Civil War illustrations and later, evocative watercolors.

Gibson as Editor and Owner of Life Magazine

In 1905, Gibson took a hiatus from illustration to pursue oil painting, a medium often considered more "serious" by the art establishment of the time. He spent several years in Europe focusing on painting, but while his paintings were competent, they never achieved the acclaim or cultural impact of his illustrations. He eventually returned to his true métier.

A significant development in his later career was his acquisition of Life magazine. In 1920, following the death of its co-founder John Ames Mitchell, Gibson bought the magazine. He took over as editor and publisher, aiming to revitalize the publication that had been so instrumental in his own success. He brought his artistic sensibilities and understanding of popular taste to the magazine's management, featuring his own work and that of other talented illustrators. Under his stewardship, Life continued to be a prominent voice in American popular culture, though it faced increasing competition from new media and changing tastes. He eventually sold the magazine in 1932, a few years before it was re-launched by Henry Luce as a photojournalism-centric publication. His tenure at Life demonstrated his business acumen and his commitment to the field of illustration.

Wartime Contributions

During World War I, Charles Dana Gibson, like many artists, dedicated his talents to the war effort. He was appointed head of the Division of Pictorial Publicity, part of President Woodrow Wilson's Committee on Public Information. In this role, Gibson mobilized artists across the country to create posters and illustrations that would support the war, encourage enlistment, promote the sale of Liberty Bonds, and foster patriotic sentiment.

His own wartime posters were powerful and evocative, often employing allegorical figures and patriotic themes. He understood the persuasive power of images and used his considerable skill to create compelling visual messages. This work, while different in tone and purpose from his society illustrations, demonstrated his versatility and his commitment to national service. His leadership in organizing the artistic community for propaganda purposes was a significant contribution to the American war effort, paralleling the work of artists in other Allied nations. He worked alongside artists like Howard Chandler Christy, known for his "Christy Girl" and patriotic posters.

Later Years and Legacy

After the First World War, the cultural landscape began to change. The Roaring Twenties brought new fashions, new social norms, and new artistic styles. The flapper, with her bobbed hair and shorter skirts, supplanted the Gibson Girl as the dominant female ideal. While Gibson continued to work, his style, so perfectly attuned to the pre-war era, seemed less in step with the frenetic energy of the Jazz Age. Norman Rockwell, for instance, was rising to prominence with a different, more homespun and nostalgic vision of America for The Saturday Evening Post.

Gibson increasingly turned his attention to oil painting in his later years, though he never fully abandoned illustration. He was elected to the National Academy of Design and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, recognition of his significant contributions to American art. He retired from active illustration in the 1930s.

Charles Dana Gibson passed away in 1944 at the age of 77. He was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His legacy, however, endures. The Gibson Girl remains an instantly recognizable icon, a symbol of a bygone era's aspirations and ideals. His drawings are prized by collectors and museums, valued not only for their artistic merit but also as historical documents that offer a window into American society at the turn of the 20th century. His influence on the art of illustration was profound, setting a standard for elegance, wit, and technical skill. Artists like Al Parker and Coby Whitmore, who became prominent illustrators in the mid-20th century, inherited a field that Gibson had helped to define and elevate.

Enduring Appeal and Art Historical Significance

The enduring appeal of Charles Dana Gibson's work lies in its combination of aesthetic beauty, technical brilliance, and insightful social commentary. He was more than just a creator of pretty pictures; he was a visual storyteller, a satirist, and a shaper of cultural ideals. His depiction of the "New Woman" in the form of the Gibson Girl was a landmark in the representation of women in popular culture, reflecting and influencing changing societal roles.

Art historians recognize Gibson as a key figure in the Golden Age of American Illustration. His ability to capture the nuances of social interaction, his elegant line, and his creation of a national icon place him in the pantheon of great American graphic artists. His work provides a rich tapestry of American life during a period of significant transformation, from the Gilded Age through the Progressive Era and World War I. He navigated the worlds of popular culture and fine art, leaving an indelible mark on both. His influence can even be seen as a precursor to the way modern advertising and media create and disseminate aspirational images. The legacy of artists like Charles Keene and Phil May, British illustrators known for their social observation in publications like Punch, can be seen as an antecedent to Gibson's own keen eye for societal detail, which he then translated into a uniquely American idiom.

In conclusion, Charles Dana Gibson was a pivotal artist whose work defined an era. Through the iconic Gibson Girl and his broader body of illustrations, he not only reflected the American scene but also helped to shape its ideals of beauty, independence, and social grace. His mastery of pen and ink, his witty observations, and his profound cultural impact ensure his lasting importance in the annals of American art history.