Victor Coleman Anderson, an American artist whose career spanned a significant period of change and development in the world of illustration, left behind a body of work that captures the spirit and sentiment of his time. Born on June 28, 1897, and passing on February 11, 1973, Anderson's life as an artist coincided with the latter part of the "Golden Age of American Illustration" and its evolution into the mid-20th century. His contributions, though perhaps not as widely celebrated today as some of his contemporaries, offer a valuable window into the visual culture and narrative traditions of American art.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

While specific details of Victor Coleman Anderson's earliest years and formal artistic training are not always extensively documented in readily accessible sources, it is typical for artists of his generation to have shown an early proclivity for drawing and visual storytelling. The late 19th and early 20th centuries in America saw a burgeoning appreciation for illustration, fueled by advancements in printing technology and the rise of popular magazines and illustrated books. This environment would have provided a fertile ground for a young individual with artistic talent to consider a career in the visual arts.

Many aspiring illustrators of that era sought training at established art institutions such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Art Students League of New York, or through apprenticeships with established artists. The influence of seminal figures like Howard Pyle, who taught many of the leading illustrators of the Golden Age, was pervasive. While Anderson's direct tutelage under such figures isn't explicitly detailed in the provided information, the stylistic currents and professional standards of the time would have undoubtedly shaped his development.

The Craft of an Illustrator in a Changing World

Anderson practiced his art during a period when illustration was a dominant force in visual communication. Illustrators were the image-makers for a vast public, creating the visuals for stories in magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, and Harper's Monthly, as well as for books, advertisements, and calendars. Their work was not merely decorative; it was integral to the narrative, helping to convey emotion, character, and setting, often becoming as memorable as the text itself.

The role demanded versatility. An illustrator needed to be adept at figure drawing, composition, and understanding historical or contemporary details to create convincing scenes. They worked in various media, including oil, watercolor, gouache, and pen and ink, adapting their techniques to the requirements of reproduction. Anderson's career would have navigated these professional demands, producing work that met the expectations of publishers and resonated with the public.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

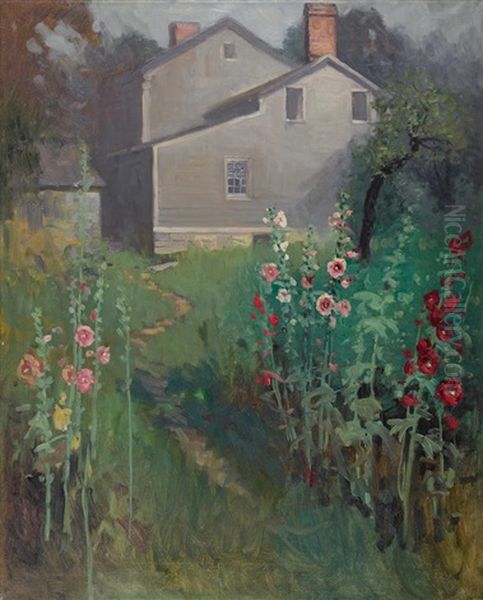

Based on the mention of his oil painting "Hollyhock Time," one can infer that Anderson's style likely leaned towards a form of narrative realism, imbued with a certain warmth and accessibility. "Hollyhock Time" suggests an interest in genre scenes, perhaps depicting everyday life, pastoral settings, or moments of quiet charm, which were popular themes in American illustration. Such subjects often aimed to evoke nostalgia, celebrate simple virtues, or tell a relatable human story.

The quality of light, the rendering of textures, and the ability to capture expressive figures would have been key components of his style. Like many illustrators of his time, Anderson's work would have aimed for clarity and immediate impact, ensuring that the image effectively communicated its intended message or story beat. The emotional content was often paramount, seeking to engage the viewer's empathy and imagination. His approach would have balanced artistic integrity with the practical needs of commercial reproduction.

"Hollyhock Time": A Glimpse into His Oeuvre

While a comprehensive list of Victor Coleman Anderson's representative works is not fully provided, "Hollyhock Time" stands out as a specifically mentioned piece. This oil painting likely exemplifies his thematic concerns and stylistic approach. One can imagine a scene bathed in the soft light of a summer's day, with hollyhocks—tall, stately flowers often associated with cottage gardens and a sense of rustic charm—forming a vibrant backdrop or a central motif.

The painting might depict children at play, a quiet domestic scene, or a moment of reflection in a garden setting. The choice of oil as a medium suggests a work of some substance, perhaps intended for exhibition or as a significant illustration. The title itself evokes a sense of seasonality and the passage of time, themes that resonate with a broad audience. Without viewing the image, we can surmise it aimed to capture a feeling of warmth, beauty, and perhaps a touch of sentimentality, characteristic of much illustrative work from that period.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Victor Coleman Anderson worked within a rich and competitive artistic landscape. The field of American illustration during his active years was populated by numerous talented individuals, each contributing to the visual tapestry of the nation. Understanding his work benefits from considering it alongside that of his contemporaries.

Artists like N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945) were giants of the era, known for their dramatic and evocative illustrations for classic adventure stories. Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) captivated audiences with his luminous colors and fantastical imagery, particularly his signature "Parrish blue." The sophisticated and stylish work of J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), especially his iconic covers for The Saturday Evening Post and Arrow Collar advertisements, defined an era of American elegance.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), perhaps the most famous American illustrator, was a direct contemporary whose career overlapped significantly with Anderson's. Rockwell's detailed and heartwarming depictions of American life set a high bar for narrative illustration. Female illustrators also made significant contributions, with artists like Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954), and Violet Oakley (1874-1961)—all students of Howard Pyle—carving out successful careers with their distinctive styles, often focusing on themes of childhood and domesticity.

In the realm of Western art, which sometimes intersected with mainstream illustration, figures like Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) had earlier established powerful visual narratives of the American West, influencing subsequent generations. The mention of Anderson's work potentially being exhibited at the "Masters of the American West Exhibition and Sale" at the Autry National Center suggests an affinity for or contribution to this genre, placing him in a lineage that includes these masters and later artists who continued to explore Western themes.

The information also notes a collaboration with Paul Collins (born 1936), a contemporary artist known for his portraiture and depictions of the human condition, particularly within African American and Native American communities. If this collaboration occurred later in Anderson's life or if there's another Paul Collins from an earlier period, it would indicate Anderson's continued engagement with the art world and potentially an evolution or broadening of his artistic interactions. Given the birth year of the more widely known Paul Collins, such a collaboration would likely have been in Anderson's later years. Other notable illustrators from the period whose work formed the backdrop to Anderson's career include Dean Cornwell (1892-1960), known as the "Dean of Illustrators," and Harvey Dunn (1884-1952), another influential student of Pyle who also became a respected teacher.

Exhibitions and Recognition

The public display of an artist's work is crucial for recognition and engagement. The mention that Anderson's painting "Hollyhock Time" was exhibited indicates that his work was seen beyond its published form. Furthermore, the possibility of his inclusion in the "Masters of the American West Exhibition and Sale" at the Autry National Center in Los Angeles is significant. This annual event is a prestigious showcase for Western American art, featuring works by leading contemporary artists and often paying homage to historical figures in the genre. If Anderson's work was featured there, it would underscore his connection to Western themes or a recognition of his skill in a manner that aligned with the exhibition's standards.

Such exhibitions provide artists with a platform to reach collectors, critics, and the broader public, contributing to their reputation and the market for their work. For an illustrator, whose primary audience was often reached through mass media, gallery or museum exhibitions offered a different kind of validation and an opportunity for the original artworks to be appreciated for their intrinsic qualities.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

As the 20th century progressed, the field of illustration underwent significant changes. The rise of photography began to challenge the dominance of hand-drawn illustrations in magazines and advertising. Artistic styles also evolved, with modernism and abstraction gaining prominence in the fine art world, which sometimes created a critical distance from the more narrative and representational styles common in illustration.

Artists like Anderson would have had to adapt to these shifting tides, perhaps by focusing on specific niches, such as book illustration or genre painting, or by evolving their style. His career extended into the 1970s, a period by which illustration had diversified into many forms, from graphic design to comic art and conceptual illustration.

Victor Coleman Anderson's legacy lies in his contribution to the rich tradition of American illustration. His works, like "Hollyhock Time," serve as visual documents of their era, reflecting its tastes, values, and stories. While he may not have achieved the household-name status of a Rockwell or a Wyeth, his dedication to his craft and his ability to connect with an audience through his art are characteristic of the many talented illustrators who shaped America's visual culture. The artists of his generation collectively created a vast and influential body of work that continues to inform our understanding of American history and identity.

The collection and preservation of works by illustrators like Anderson are vital. Institutions that house collections of American illustration, such as the Norman Rockwell Museum, the Delaware Art Museum (with its strong holdings of Howard Pyle and his students), and various university archives and specialized collections, play a crucial role in ensuring that these contributions are not forgotten. Each piece, whether a preliminary sketch, a finished painting for reproduction, or an independent work, adds a piece to the puzzle of American art history.

Conclusion: Appreciating a Narrative Artist

Victor Coleman Anderson, active from 1897 to 1973, was an American illustrator who participated in a vibrant and essential field of artistic production. His work, characterized by a narrative and likely realistic style, contributed to the visual storytelling that was so central to American popular culture during his lifetime. Through pieces like "Hollyhock Time" and his engagement with the broader artistic community, including potential collaborations and exhibitions, Anderson carved out his place in the annals of American illustration.

By studying his art alongside that of his renowned contemporaries—such as Norman Rockwell, N.C. Wyeth, J.C. Leyendecker, and Maxfield Parrish—we gain a fuller appreciation for the depth and diversity of this field. His dedication to the craft, his ability to evoke emotion and tell stories through images, and his participation in the cultural life of his time make Victor Coleman Anderson a figure worthy of remembrance and further study within the history of American art. His paintings and illustrations offer windows into the past, rendered with the skill and sensitivity of a dedicated professional.