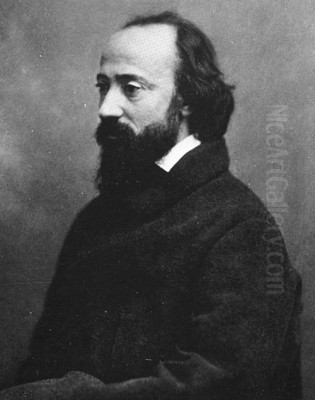

Charles-François Daubigny stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Born into a world where academic tradition still held considerable sway, he became a vital member of the Barbizon School and, more significantly, a crucial forerunner of the Impressionist movement. His dedication to painting directly from nature, his innovative use of a floating studio, and his evolving, light-filled style marked him as a transitional artist whose work bridged the gap between realism and the revolutionary art that would follow. His life and art tell a story of perseverance, a deep love for the French countryside, and a quiet but profound impact on the course of modern art.

An Artistic Heritage and Early Struggles

Charles-François Daubigny entered the world on February 15, 1817, in Paris, France. His path into art seemed almost predestined, as he was born into a family deeply immersed in creative pursuits. His father, Edme-François Daubigny, was himself a landscape painter, providing an immediate artistic environment for the young Charles-François. Adding to the family's artistic inclinations was his uncle, Pierre Daubigny, who worked as a miniature sculptor. This familial background undoubtedly nurtured his innate talents from an early age.

Despite this artistic lineage, the Daubigny family was not affluent. Financial constraints were a significant factor in his early life, preventing him from accessing the formal training offered by prestigious art academies. This lack of conventional schooling forced Daubigny to find alternative ways to support himself and hone his craft. His childhood was also marked by frail health, which led to him being sent away from Paris to be raised by a nurse in the village of Valmondois, near the Oise River. This period spent immersed in the countryside likely instilled in him a profound connection to nature that would define his artistic career.

To make ends meet during his formative years, Daubigny undertook practical work that kept him close to the art world, albeit on its periphery. He found employment creating illustrations for various publishers, a common way for aspiring artists to earn a living. Additionally, he worked as a picture restorer at the Louvre Museum. This role, while perhaps less glamorous than creating original art, provided invaluable, hands-on experience with the techniques and materials of the Old Masters, offering a unique form of education.

Finding His Path: Italy and Early Landscapes

Driven by a desire to further his artistic development, Daubigny saved enough money for a formative trip. Around 1835 or 1836, he embarked on a journey to Italy, a near-essential pilgrimage for aspiring artists of the era. Exposure to the Italian landscape, the classical ruins, and the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque periods broadened his horizons. While his later work would focus intensely on the French landscape, the Italian sojourn undoubtedly contributed to his understanding of light, composition, and artistic tradition.

Upon returning to Paris, Daubigny sought more structured, albeit brief, training. He entered the studio of Paul Delaroche, a prominent historical painter known for his polished, academic style. While Daubigny's mature work would diverge significantly from Delaroche's meticulous approach, this period likely provided him with foundational skills and exposure to the professional art scene in Paris.

Daubigny began seriously focusing on landscape painting around 1836, exploring the areas surrounding Paris. His official debut at the prestigious Paris Salon came in 1838 with a painting titled Notre Dame and Île Saint-Louis. He exhibited again at the Salon in 1840. However, these early works, likely still reflecting more traditional influences, did not immediately capture widespread attention or critical acclaim. The 1840s saw him continue to rely heavily on graphic work, producing numerous etchings and illustrations, further developing his skills in composition and line.

The Barbizon Connection: Nature as Teacher

Around 1843, Daubigny began spending significant time near the village of Barbizon, situated on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau. This area had become a magnet for a group of landscape painters seeking to escape the confines of studio practice and engage directly with nature. These artists, including figures like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, formed the core of what became known as the Barbizon School.

Daubigny became closely associated with this group, sharing their commitment to naturalism and direct observation. He formed a particularly strong and lasting friendship with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, one of the leading figures of the school, known for his poetic and light-sensitive landscapes. The two artists often traveled and painted together, sharing insights and mutual respect. Daubigny's studio in Auvers-sur-Oise, known as "Vallées des Gonesse," later became a gathering place for artists, fostering camaraderie and artistic exchange.

However, it's important to note that while Daubigny is firmly placed within the Barbizon orbit, he never actually resided permanently in the village itself. His primary subjects were often found not in the dense forest but along the rivers, particularly the Seine and his beloved Oise, near where he had spent part of his childhood. His approach, while rooted in the Barbizon ethos of truth to nature, developed its own distinct characteristics, focusing increasingly on water, atmosphere, and the transient effects of light.

"Le Botin": The Floating Studio

A defining moment in Daubigny's career, and a testament to his innovative spirit, came in 1857. He acquired a small ferry or barge, christened it "Le Botin" (The Little Box), and ingeniously converted it into a floating studio. This mobile atelier allowed him unprecedented freedom and intimacy with his chosen subjects: the rivers of France. He could navigate the Seine and the Oise, anchoring wherever a scene captured his interest, painting directly from the water's perspective at different times of day and under varying weather conditions.

This unique working method profoundly shaped his art. Painting from the boat enabled him to study the subtle interplay of light on water, the reflections of the sky and riverbanks, and the specific atmospheric conditions of the riverside environment. It allowed him to capture the fluidity and ever-changing nature of the river landscape with remarkable immediacy. "Le Botin" became synonymous with Daubigny, a symbol of his dedication to plein air (outdoor) painting and his departure from traditional studio methods.

His voyages on "Le Botin" were not always solitary. He sometimes invited fellow artists to join him, sharing his unique vantage point. Younger painters, including the future Impressionists Claude Monet and possibly Paul Cézanne, were among those who experienced Daubigny's floating studio, absorbing his methods and his deep connection to the riverine environment. This practice further cemented his role as a mentor and a bridge to the next generation.

Evolving Style: Towards Impressionism

Daubigny's artistic style underwent a noticeable evolution throughout his career, moving away from the tighter, more detailed approach of his early years towards a looser, more atmospheric, and light-focused manner that clearly anticipated Impressionism. His commitment to plein air painting was central to this transformation. Working outdoors, often rapidly to capture fleeting effects of light and weather, encouraged a more spontaneous and abbreviated brushstroke.

He became particularly adept at rendering specific times of day and atmospheric conditions. His canvases often depict the gentle light of dawn, the warm glow of dusk, or the silvery luminescence of moonlight reflecting on the water. He wasn't merely recording topography; he was capturing mood and sensation. Works like Moonlight on the Banks of the Oise or simply Moonlight (both potentially referring to similar works from around 1864) exemplify this fascination with nocturnal or crepuscular light.

His color palette softened, and his application of paint became freer. He explored techniques like painting wet-on-wet to achieve softer transitions and atmospheric effects. He was also open to using newly available synthetic pigments that offered brighter hues, helping him capture the vibrancy of natural light. Critics sometimes faulted his later works for their sketch-like "unfinished" appearance, finding his looser handling lacking the polish of academic painting. However, it was precisely this freedom and emphasis on capturing the immediate visual sensation that made his work so groundbreaking and influential for the Impressionists.

Key Themes and Masterworks

The rivers of France, especially the Seine and the Oise, were Daubigny's most consistent and beloved subjects. His paintings often feature tranquil stretches of water, tree-lined banks, small boats, and reflections playing on the surface. He depicted the quiet, everyday beauty of the French countryside – fields, orchards, and villages nestled along the waterways.

Among his most celebrated works is Spring (1857), now housed in the Louvre. Considered one of his most ambitious Salon paintings, it captures the fresh, burgeoning life of the season with characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere. Other significant works include variations on the theme of returning flocks or shepherds at dusk, such as The Return of the Flock (1858) or The Shepherd's Return (1864), which convey a sense of pastoral peace and the gentle melancholy of twilight.

His river scenes are numerous and iconic. The Banks of the Loing (1850) and Sunset on the Loing (1850) show his early mastery of riverine landscapes. Later works like On the Banks of the Seine at Nightfall (1864) and The Seine: Morning (1874) demonstrate his continued exploration of light effects on water at different times of day. His trip to Italy is recalled in Moonlight at Orvieto (1864). Even seemingly simple subjects, like Apple Blossoms (1873) or Boats at Etaples (1871), are rendered with a freshness and immediacy that highlights his observational skills and evolving technique. Cottages at Barbizon, Evening (1864) shows his continued connection to the area, captured with his signature atmospheric touch.

Interactions with Contemporaries and Mentorship

Daubigny was a sociable figure within the Parisian art world, maintaining relationships with a wide range of artists. His closest bond was arguably with Camille Corot, with whom he shared travels, artistic ideals, and a deep friendship. His studio in Auvers-sur-Oise served as a welcoming hub, attracting artists associated with the Barbizon school like Armand Leleux (though sources sometimes vary on specific names like Ludwig Piette or Edouard Béliard, who were perhaps more linked to Pissarro later). The great caricaturist and painter Honoré Daumier was also known to attend gatherings there.

His connection with the Realist painter Gustave Courbet was also significant. A notable encounter occurred in the summer of 1865 when Daubigny spent time in Trouville on the Normandy coast alongside Courbet, the marine painter Eugène Boudin, and the young Claude Monet. This period of shared work and discussion, particularly the exposure to Boudin's and Daubigny's plein air methods, proved highly influential for Monet's development.

Daubigny played a crucial role as a mentor and supporter of younger artists who would soon spearhead the Impressionist movement. He recognized the talent of Monet and Camille Pissarro early on. As a member of the Salon jury, he sometimes advocated for the inclusion of works by these and other innovative painters who faced rejection from more conservative members. There are accounts suggesting he actively supported Monet, perhaps even assisting with exhibition opportunities around 1868, demonstrating his generosity and foresight. His influence extended to artists like Johan Barthold Jongkind, another important precursor to Impressionism known for his atmospheric watercolors and marines, whom Daubigny knew and respected.

A Master Printmaker

Beyond his significant achievements in oil painting, Charles-François Daubigny was also a highly accomplished and prolific printmaker, particularly skilled in etching. His work in this medium paralleled his painted landscapes, often depicting similar river scenes, rural vistas, and atmospheric effects. He approached etching with the same sensitivity to light and texture that characterized his paintings.

His etchings were admired for their technical skill and artistic expression. He produced numerous plates throughout his career, sometimes issued in albums or series, such as the "Voyage en Bateau" (Boat Trip) series, which directly reflected his experiences on "Le Botin." His graphic work was not merely a sideline; it was an integral part of his artistic output, allowing him to explore compositional ideas and reach a wider audience. One account mentions him producing an impressive seventeen etchings in a single year, highlighting his dedication to the medium. His prints are valued for their delicate lines, rich tonal variations, and ability to convey the essence of the landscape.

Recognition and Honors

While some conservative critics remained skeptical of his increasingly loose style, Daubigny achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime, particularly from the 1850s onwards. His works were regularly accepted at the Salon, and he received several official accolades. His painting was praised, especially after the 1848 Salon, for its direct and honest portrayal of nature, free from overt poeticizing or subjective interpretation.

The French government acknowledged his contributions to the arts. He was awarded the Legion of Honour, first being made a Knight (Chevalier) in 1859 (some sources say 1869, clarification needed, but official recognition occurred) and later promoted to Officer in 1874. These honors signified his established position within the French art world, even as his style pushed boundaries. His paintings were acquired by the state and entered important public collections.

Legacy: The Bridge to Impressionism

Charles-François Daubigny passed away in Paris on February 19, 1878, at the age of 61. He left behind a substantial body of work and a significant legacy as a key transitional figure in French art. While firmly rooted in the naturalism of the Barbizon School, his innovations directly paved the way for Impressionism.

His unwavering commitment to plein air painting, epitomized by his studio boat, demonstrated a new way of engaging with the landscape, prioritizing direct observation and sensory experience over studio conventions. His focus on capturing the fleeting effects of light, water, and atmosphere, and his development of a looser, more suggestive brushstroke, provided a crucial precedent for Monet, Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and other Impressionists. They admired his ability to convey mood and immediacy.

Even artists beyond the core Impressionist group felt his influence. Vincent van Gogh, during his time in Auvers-sur-Oise (where Daubigny had lived and worked), deeply admired Daubigny's landscapes and painted several homages, including depictions of Daubigny's garden. This demonstrates the enduring respect Daubigny commanded among later generations.

Today, Daubigny is celebrated as a major landscape painter in his own right and as an indispensable link in the evolution of modern art. His works are held in the world's most prestigious museums, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Mesdag Museum in The Hague. His paintings continue to charm viewers with their tranquil beauty, their honest depiction of the French countryside, and their masterful rendering of light and water, securing his place as a gentle revolutionary of landscape painting.