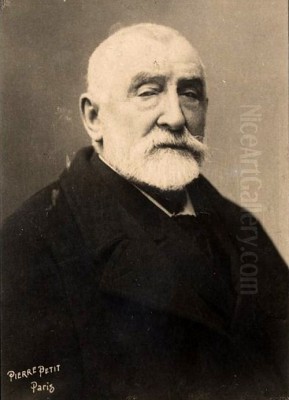

Henri-Joseph Harpignies stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of 19th and early 20th-century French art. Spanning a remarkably long life from 1819 to 1916, he dedicated his career almost exclusively to landscape painting, becoming renowned for his sensitive depictions of the French countryside, his mastery of both oil and watercolor, and his deep connection to the principles of the Barbizon School, even while forging his own distinct path. His work, characterized by structural solidity, careful observation of nature, and a profound understanding of light, earned him considerable acclaim during his lifetime and secured his place in the annals of art history.

Early Life and a Late Artistic Calling

Born on July 28, 1819, in Valenciennes, a town in northern France with a notable artistic heritage (being the birthplace of Antoine Watteau), Henri-Joseph Harpignies came from a background of relative comfort. His family was involved in business, often cited as sugar refining or manufacturing, and it was initially expected that young Henri would follow a commercial path. His early years involved some travel related to business pursuits, but the pull towards art proved irresistible, albeit manifesting later than for many artists.

Unlike prodigies who show talent from childhood, Harpignies did not commit to a formal artistic career until he was twenty-seven years old. This relatively late start, however, did not hinder his eventual success. Around 1846, he made the decisive move to Paris to pursue painting seriously. His first significant teacher was Jean-Alexis Achard, a landscape painter from Grenoble. Under Achard's guidance, Harpignies began to hone his skills in drawing and painting, focusing on the direct study of nature, a principle that would remain central to his art throughout his long career. He traveled with Achard, absorbing lessons not just in technique but also in the patient observation required for landscape art.

The Formative Influence of Italy

Like many artists before and after him, Harpignies felt the magnetic pull of Italy. He undertook his first major trip south around 1849, staying until perhaps 1852. This journey was profoundly formative. He immersed himself in the Italian landscape, captivated by its classical ruins, umbrella pines, luminous skies, and the unique quality of Mediterranean light. He studied the works of Old Masters, likely paying close attention to the foundational landscape traditions established by artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose idealized yet structured visions of nature had shaped European landscape painting for centuries.

This initial Italian sojourn helped Harpignies develop a stronger sense of composition and a greater appreciation for atmospheric effects. He returned to France with a refined eye and a growing technical assurance. However, Italy's influence was not a one-time event. He would return later, most notably between 1863 and 1865. This second extended stay proved even more crucial, particularly because it was during this time in Rome that he solidified his friendship with Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, one of the most revered landscape painters of the era.

Corot and the Barbizon Connection

The relationship with Corot was pivotal for Harpignies. Although nearly twenty-five years older, Corot became a mentor figure and a close friend. Harpignies deeply admired Corot's ability to combine poetic sensitivity with structural rigor in his landscapes. While Harpignies never fully adopted Corot's often feathery brushwork or hazy atmospheres, he absorbed lessons about tonal harmony, balanced composition, and the importance of capturing the underlying mood or 'sentiment' of a place.

Through Corot and his own inclinations, Harpignies became closely associated with the Barbizon School. This group of painters, active from the 1830s onwards, rejected academic conventions and instead championed realism and painting directly from nature, often working in the Forest of Fontainebleau near the village of Barbizon. Key figures included Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Jules Dupré, Constant Troyon, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña. Harpignies shared their commitment to truthful representation and their love for the unadorned French countryside.

While sometimes considered a later exponent or fellow traveler rather than a core member of the original group, Harpignies embodied the Barbizon spirit. He spent considerable time painting outdoors, creating sketches and studies that would inform his larger studio canvases. His work, like that of the Barbizon painters, celebrated the beauty of rural France – its forests, rivers, fields, and villages – with sincerity and a lack of overt romanticization. He particularly admired Daubigny's river scenes and shared his interest in capturing the effects of light on water.

A Distinctive Landscape Style: Structure and Light

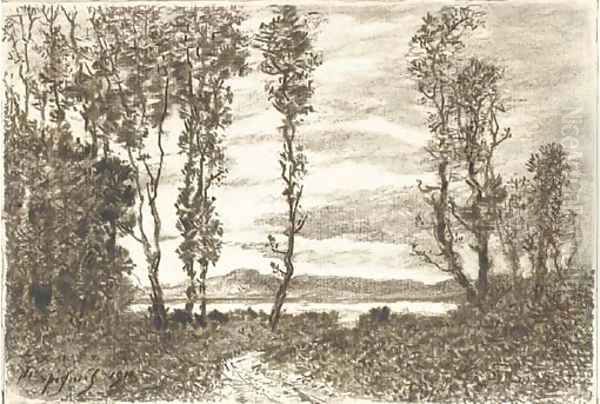

Despite his connections to Achard, Corot, and the Barbizon group, Harpignies developed a highly personal and recognizable style. His paintings are often characterized by strong, clear drawing and a sense of structural solidity. This is particularly evident in his treatment of trees, which he rendered with such anatomical accuracy and individual character that he earned the admiring nickname "The Michelangelo of Trees." He understood the underlying form of a tree – its trunk, branches, and foliage – and depicted it with convincing weight and volume.

His compositions are typically well-ordered and balanced, often featuring a strong diagonal element, such as a receding road or riverbank, to lead the viewer's eye into the landscape. He favored clear, natural light, often depicting scenes under the bright skies of midday or the gentle illumination of morning or late afternoon. While capable of capturing subtle atmospheric effects, his work generally possesses a clarity and definition that distinguishes it from the softer, more diffused light often found in Corot's later works or the atmospheric explorations of the Impressionists.

Harpignies painted various regions of France, including the Île-de-France, Picardy, the Nivernais, the Bourbonnais, and the Auvergne, as well as scenes from his travels in Italy. River landscapes were a recurring theme, with works depicting the Seine, Loire, Allier, and Rhône rivers. He was adept at capturing the reflections in water and the interplay of light between sky, land, and river. Works like View of the Seine or The Banks of the Allier exemplify his skill in rendering these tranquil, well-structured waterscapes.

Master of Watercolor

Alongside his achievements in oil painting, Harpignies was a consummate master of watercolor. He approached this medium with the same seriousness and dedication as oil, recognizing its unique potential for capturing spontaneity and luminosity. His watercolors are noted for their freshness, transparency, and confident draftsmanship. He often used watercolor for preparatory studies outdoors, but he also created highly finished exhibition pieces in the medium.

His technique was fluid yet controlled, often combining transparent washes with precise linear details applied with the brush. He understood how to preserve the white of the paper to represent highlights and create a sense of airiness. His mastery contributed significantly to the growing appreciation of watercolor as an independent art form in France during the latter half of the 19th century. He was, in fact, a founding member of the Société d'aquarellistes français (Society of French Watercolourists), further cementing his role as a champion of the medium. Many critics and collectors admired his watercolors as much, if not more, than his oils for their immediacy and brilliance.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Throughout his long career, certain themes and subjects recurred in Harpignies' work. Trees, as mentioned, were a constant fascination, depicted individually as majestic specimens or grouped in forests and groves. Water, in the form of rivers, ponds, and coastal views, was another favorite subject, allowing him to explore reflections and light. Rural architecture, such as farmhouses, mills, and village churches, often features in his landscapes, providing points of human interest and anchoring the compositions.

Among his many notable works, several stand out as representative of his style and concerns:

The Lofty Trees (Les Chênes du Château-Renard): Exhibited at the Salon, this work showcases his powerful depiction of trees, emphasizing their structure and grandeur.

Moonrise (Lever de lune) (1885, Musée d'Orsay): A poetic landscape capturing the subtle light and tranquil atmosphere of twilight, demonstrating his ability to handle different lighting conditions.

Solitude (1897, Musée d'Orsay): A later work showing his continued engagement with serene, contemplative landscapes, often featuring a solitary, majestic tree.

The Painter's Garden at Saint-Privé: Depicting the garden of his final home, this work shows a more intimate side of his landscape art.

The Olive Trees at Menton: Reflecting his time on the Mediterranean coast, capturing the distinctive forms of olive trees under southern light.

View of the Seine and The Pont Neuf: Several paintings depict Paris and its river, showing his ability to handle urban landscapes with the same structural clarity as his rural scenes. These works also serve as valuable historical documents of the city.

A View of Moulins: Representing his connection to the Allier region, likely depicting the town or its surroundings with characteristic attention to place.

Banks of the Allier: A subject he returned to, capturing the peaceful river landscape that he knew well from his time in Hérisson.

View of Capri: Stemming from his Italian travels, showcasing the dramatic coastal scenery and brilliant light of the island.

These works, and many others, demonstrate his consistent vision, technical skill, and deep affection for the landscapes he painted.

Recognition, Honors, and Teaching

Harpignies achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon in 1853 (though some sources cite 1861 for his first major notice). His talent was soon acknowledged with medals in 1866, 1868, and 1869. His reputation grew steadily, and he became a respected figure in the French art world.

He was awarded the prestigious Legion of Honour, starting as a Chevalier (Knight) in 1875, progressing to Officier (Officer) in 1883, Commandeur (Commander) in 1901, and finally Grand Officier (Grand Officer) in 1911 – a testament to his esteemed position. He received the Medal of Honor at the Salon of 1897 for his overall contributions, and a Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1900. Despite these accolades, Harpignies reportedly maintained a degree of independence; one anecdote claims he declined membership in the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, although highly qualified.

Harpignies also played a role as a mentor to younger artists. He spent many summers in the village of Hérisson in the Allier department, where he attracted a circle of followers, sometimes referred to informally as the "Hérisson School." He was known to be encouraging and friendly towards aspiring painters. Among those considered his pupils or strongly influenced by him were artists like Émile Appay and Léon-Victor Dupré (brother of the more famous Barbizon painter Jules Dupré). His approach was likely one of guidance and shared practice rather than formal academic instruction.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Harpignies' career unfolded during a period of immense change and dynamism in French art. He worked alongside the Realist movement, led by figures like Gustave Courbet, who also emphasized direct observation but often with a more socially conscious or provocative edge. More significantly, Harpignies witnessed the rise of Impressionism in the 1870s and Post-Impressionism thereafter.

While he shared the Impressionists' interest in light and landscape, Harpignies remained fundamentally committed to a more structured, naturalist approach rooted in the Barbizon tradition. He did not dissolve form into light and color as artists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro did. He maintained strong outlines and a sense of solid form throughout his career. Nevertheless, some of his later works, particularly watercolors, show a greater freedom and boldness in handling that might reflect a subtle awareness of contemporary trends, even as he adhered to his own vision.

His contemporaries included not only the Barbizon painters and Impressionists but also other landscape artists pursuing different paths. He worked alongside Paul Flandrin for a time near Compiègne. He knew figures like Auguste Ravier and Hector Allemand, who were also active landscape painters. His long life meant he saw the emergence of Fauvism and Cubism, styles radically different from his own steadfast dedication to representational landscape art.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Harpignies remained remarkably active and productive well into his old age. His eyesight reportedly remained sharp, and he continued to paint with vigor even in his nineties. He eventually purchased a house, La Trémellerie, in Saint-Privé in the Yonne department, and divided his time between Paris, Saint-Privé, and travels, often to the south of France during winter. He continued to exhibit and enjoyed a status as a venerable patriarch of French landscape painting.

He died on August 28, 1916, at Saint-Privé, having reached the advanced age of 97. His life had spanned monarchies, republics, revolutions, and the dawn of modernism. Through it all, he remained dedicated to his chosen genre, creating a vast body of work characterized by its consistency, technical excellence, and sincere love of nature.

Today, Henri-Joseph Harpignies is remembered as a leading landscape painter of the second half of the 19th century. He serves as an important link between the Barbizon School and later landscape traditions. While perhaps not as revolutionary as the Impressionists, his work possesses an enduring appeal due to its clarity, structural integrity, and tranquil beauty. His paintings and watercolors are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and many other institutions across Europe and North America.

Conclusion

Henri-Joseph Harpignies carved out a unique and respected place in French art history. Starting his artistic journey relatively late, he quickly developed a distinctive style grounded in the careful observation of nature, influenced by his teacher Achard, his travels in Italy, and his close association with Corot and the Barbizon School. Renowned for his masterful drawing, particularly of trees, and his exceptional skill in both oil and watercolor, he created a legacy of landscapes that celebrate the beauty and structure of the French countryside. His long, productive life and the consistent quality of his output earned him numerous honors and a lasting reputation as a steadfast master of landscape painting, whose works continue to offer viewers a sense of peace, order, and connection to the natural world.