Charles Le Brun stands as a colossus in the landscape of 17th-century French art. More than just a painter, he was an administrator, theorist, designer, and the principal orchestrator of the visual culture that defined the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King. His influence permeated nearly every aspect of artistic production, from monumental paintings and grand decorative schemes to tapestries and furniture. As the dominant figure in the French artistic establishment for decades, Le Brun shaped the very definition of French classicism and the opulent Baroque style that became synonymous with the power and prestige of the French monarchy during the Grand Siècle (Great Century). His life and career offer a fascinating insight into the intersection of art, power, and national identity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris on February 24, 1619, Charles Le Brun's artistic inclinations were perhaps nurtured by his family environment. His father, Nicolas Le Brun, was a sculptor, suggesting an early exposure to the visual arts. His mother, Julienne Le Blé, came from a family with connections to the nobility, which may have facilitated his entry into influential circles later in life. Recognizing his prodigious talent at a young age, Le Brun was fortunate to attract powerful patronage early on.

By the age of eleven, he was placed under the protection of Pierre Séguier, Chancellor of France, a pivotal figure who would remain a significant supporter. This patronage opened doors for the young artist. Around the age of thirteen, Le Brun entered the studio of François Perrier, a painter who had spent time in Italy and could offer insights into the Italian masters. However, his most significant early training came under Simon Vouet, who had returned from Italy in 1627 and rapidly became the leading painter in Paris.

Vouet's studio was the premier training ground for aspiring artists in France at the time. Under Vouet, Le Brun absorbed the lessons of the Italian Baroque, characterized by dynamic compositions, rich color, and dramatic intensity, which Vouet had adapted to French tastes. Even in his youth, Le Brun demonstrated remarkable skill. A testament to his early abilities is the painting Hercules and the Horses of Diomedes, believed to have been created when he was only around fifteen years old. This surviving early work already hints at the energy and compositional confidence that would mark his mature style.

The Crucial Roman Sojourn

The trajectory of Le Brun's career took a decisive turn in 1642 when, thanks to the continued support of Chancellor Séguier, he traveled to Rome. Italy, particularly Rome, was considered the essential finishing school for any ambitious European artist. It was here that artists could study firsthand the masterpieces of antiquity and the High Renaissance, as well as the works of contemporary Italian Baroque masters. For Le Brun, however, the most significant aspect of his Roman stay was his encounter and subsequent study with Nicolas Poussin.

Poussin, a fellow Frenchman who had made Rome his home, was already revered as a master of classicism. His work emphasized order, clarity, intellectual rigor, and drawing (disegno) over color (colore). He drew inspiration from classical sculpture and the paintings of Raphael, creating compositions marked by balance, restraint, and profound historical or mythological themes. Le Brun spent approximately four years in Rome, from 1642 to 1646, working closely with Poussin.

While Le Brun never fully abandoned the dynamism inherent in the Baroque style he learned from Vouet, his time with Poussin instilled in him a deep appreciation for classical principles, narrative clarity, and the importance of historical accuracy and decorum in painting. Poussin's influence is evident in Le Brun's increased emphasis on structured composition and the careful articulation of human figures and emotions. Works created during or shortly after his Roman period, such as the Sacrifice of Polyxena, demonstrate this developing synthesis of Baroque energy and classical discipline. Poussin's guidance and recommendations also helped Le Brun gain access to important patrons and collections in Rome, further enriching his artistic education.

Return to Paris and Rise to Prominence

Le Brun returned to Paris in 1646, equipped with the invaluable experience of Rome and the intellectual framework provided by Poussin. He arrived at an opportune moment. The artistic landscape was evolving, and his talent, ambition, and connections quickly propelled him forward. He found favor with influential figures, including Cardinal Richelieu, the powerful chief minister of France, for whom he undertook commissions.

His reputation grew steadily through various projects, including religious paintings and decorative schemes for private patrons. A key step in his ascent was his involvement, alongside Eustache Le Sueur and others, in the decoration of the Hôtel Lambert, a magnificent private mansion in Paris. His work there showcased his ability to handle large-scale decorative cycles, blending painting and stucco work in the Italian tradition.

However, Le Brun's ambition extended beyond individual commissions. He recognized the importance of institutional structures in shaping the art world. In 1648, alongside a group of artists seeking to elevate their status above that of mere craftsmen associated with traditional guilds, Le Brun played a crucial role in the founding of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). This institution, established under royal charter, aimed to provide structured training, establish artistic standards, and enhance the social standing of artists. Le Brun would become its driving force and eventual director, using it as a platform to promote his artistic ideals.

The Patronage of Fouquet: Vaux-le-Vicomte

Before becoming the undisputed artistic director for Louis XIV, Le Brun undertook a massive commission that significantly boosted his reputation but also became entangled in political drama. Nicolas Fouquet, the immensely wealthy and ambitious Superintendent of Finances, commissioned Le Brun in the late 1650s to oversee the decoration of his magnificent château, Vaux-le-Vicomte. This project was a collaboration between three masters who would later define the arts under Louis XIV: the architect Louis Le Vau, the landscape architect André Le Nôtre, and Le Brun himself as the painter-decorator.

At Vaux-le-Vicomte, Le Brun was given free rein to create a lavish interior that would rival royal palaces. He designed intricate ceiling paintings, stucco work, and decorative panels, notably in the King's Chamber and the Salon des Muses. His work at Vaux demonstrated his mastery of large-scale illusionistic decoration and his ability to integrate painting, sculpture, and architecture into a unified whole. He also designed tapestries for the château, showcasing his versatility.

The splendor of Vaux-le-Vicomte, however, proved to be Fouquet's undoing. When Louis XIV visited the château in 1661 for a famously extravagant fête, he was reportedly enraged by the display of wealth and power that seemed to challenge his own. Shortly thereafter, Fouquet was arrested, charged with embezzlement, and imprisoned for life. While disastrous for Fouquet, the episode inadvertently benefited Le Brun. Louis XIV, determined to surpass Vaux-le-Vicomte's magnificence at his own palaces, recognized the talent responsible for its decoration. He effectively co-opted the team of Le Vau, Le Nôtre, and Le Brun for his own grand projects, particularly the expansion and embellishment of Versailles.

Premier Peintre du Roi: Dominance under Louis XIV

The fall of Fouquet marked the beginning of Le Brun's unparalleled dominance in the French art world, facilitated by the patronage of Louis XIV and his powerful minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Colbert, who succeeded Fouquet and oversaw the arts as Superintendent of Buildings, Arts, and Manufactures, saw the arts as a crucial tool for promoting the glory of the King and the state. He found in Le Brun the perfect artist to implement this vision.

In 1664, Le Brun was officially appointed Premier Peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King). This prestigious title was more than honorary; it placed him at the apex of the artistic hierarchy, giving him precedence over all other painters working for the crown. He received a substantial pension and lodgings at the Louvre. His influence extended far beyond his personal artistic output.

Under Colbert's direction, Le Brun effectively became the artistic dictator of France. His authority was consolidated through his key positions: he was the driving force behind the Royal Academy, becoming its Chancellor in 1663 and later Director for life, shaping its curriculum and aesthetic doctrine. In 1663, he was also appointed director of the Manufacture des Gobelins.

The Royal Academy and Artistic Doctrine

Le Brun's leadership transformed the Royal Academy into the central institution governing artistic taste and training in France. He delivered lectures, established a strict hierarchy of genres (with history painting at the top), and promoted a specific doctrine based heavily on the principles of Poussin and classical art, albeit infused with a Baroque sense of grandeur suitable for the monarchy.

The Academy emphasized the primacy of drawing (disegno) over color (colore), intellectual conception over spontaneous execution, and the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters like Raphael. Le Brun's teachings stressed decorum, narrative clarity, and the accurate depiction of emotions, which he later codified in his famous lecture on the passions. This academic system aimed to produce artists capable of executing the large-scale historical and allegorical works required by the crown. While it provided rigorous training, it also tended to stifle artistic diversity, leading to later debates, such as the famous quarrel between the Poussinistes (followers of Poussin and Le Brun's emphasis on line) and the Rubénistes (advocates of color, inspired by Peter Paul Rubens, led by figures like Roger de Piles).

The Gobelins Manufactory: A Unified Royal Style

Le Brun's directorship of the Gobelins manufactory was another pillar of his power and a key instrument in creating the unified "Louis XIV style." Originally a tapestry workshop, Colbert expanded its scope under Le Brun's direction to produce virtually all the furnishings and decorative objects required for the royal palaces – not just tapestries, but also furniture, silverwork, and marquetry.

Le Brun provided designs for countless items, ensuring stylistic consistency across different media. He oversaw teams of skilled artisans, weavers, cabinetmakers, and metalsmiths. Famous tapestry series produced under his direction include The History of the King, celebrating Louis XIV's reign; The Elements; The Seasons; and the Royal Residences. These monumental works, woven with rich materials like wool, silk, and gold thread, adorned the walls of Versailles and other palaces, serving as powerful visual propaganda. The Gobelins became a model for state-sponsored craft production and played a crucial role in establishing France as the leader in luxury goods and decorative arts in Europe.

Masterpieces of Propaganda: The History of Alexander

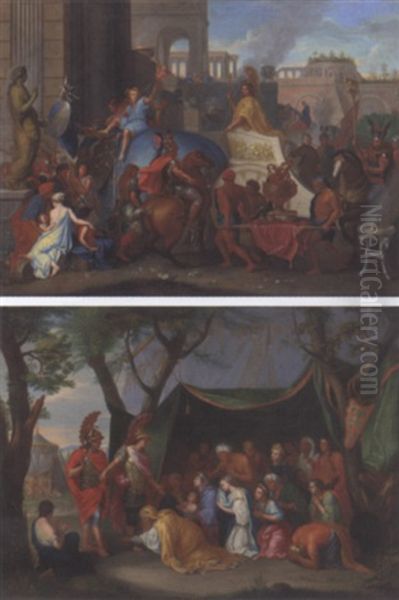

Among Le Brun's most celebrated easel paintings is the series depicting the History of Alexander the Great. Commissioned in the early 1660s, these large canvases were intended to draw parallels between the ancient Macedonian conqueror and the young Louis XIV, flattering the King by associating him with one of history's greatest military leaders.

The series includes dramatic scenes such as The Entry of Alexander into Babylon, The Battle of the Granicus, The Queens of Persia at the Feet of Alexander (also known as The Tent of Darius), and Alexander and Porus. These works exemplify Le Brun's mature style: grand compositions filled with numerous figures, dynamic action, rich detail, and expressive gestures, all rendered with classical clarity and anatomical precision. The paintings were immensely successful, widely reproduced through engravings, and cemented Le Brun's reputation as the foremost history painter of his time. They perfectly fulfilled the requirement for art that was both visually impressive and ideologically potent, glorifying heroism and magnanimous leadership, implicitly reflecting onto Louis XIV.

Versailles: The Apotheosis of Royal Glory

Le Brun's most extensive and arguably most important contribution was his work at the Palace of Versailles. As Louis XIV transformed his father's hunting lodge into the magnificent seat of the French court and government, Le Brun was entrusted with overseeing the vast decorative programs for the state apartments and grand public spaces. Working in collaboration with architects like Louis Le Vau and later Jules Hardouin-Mansart, and overseeing teams of painters and sculptors, Le Brun created some of the most iconic interiors of the Baroque era.

His earliest work at Versailles included decorations in the Queen's Apartments and the original state apartments of the King. A major, though now lost, creation was the Ambassadors' Staircase (Escalier des Ambassadeurs), the ceremonial entrance to the King's Grand Apartment. Completed in the 1670s, this monumental staircase featured elaborate illusionistic frescoes depicting figures from different nations looking down from balconies, set within a complex architectural framework combining marble, bronze, and painting. It was designed to impress visiting dignitaries with the power and global reach of the French monarchy.

Le Brun's crowning achievement at Versailles is the decoration of the Hall of Mirrors (Galerie des Glaces) and the adjoining Salons of War (Salon de la Guerre) and Peace (Salon de la Paix). Designed by Hardouin-Mansart, the Hall of Mirrors is a vast gallery lined with mirrors on one side and windows overlooking the gardens on the other. Le Brun designed the intricate vaulted ceiling, covering it with a series of large paintings set into ornate stucco frames. These paintings celebrate the first eighteen years of Louis XIV's personal rule, focusing on his military victories (particularly against the Dutch), governmental reforms, and patronage of the arts and sciences. The iconography is complex, blending historical events with allegorical figures in a triumphant assertion of the King's glory and divine right.

The Salon de la Guerre features a large oval stucco relief by Antoine Coysevox depicting Louis XIV on horseback trampling his enemies, surrounded by Le Brun's painted allegories of defeated nations. The Salon de la Paix mirrors this, with paintings by Le Brun depicting the benefits France bestows upon Europe through peace. Together, these spaces form an unparalleled ensemble of Baroque decoration, designed to overwhelm the viewer with the power, wealth, and cultural sophistication of the French monarchy under Louis XIV. Le Brun directed numerous other artists in these projects, including sculptors like François Girardon and Coysevox, ensuring adherence to his overall vision.

Le Brun the Theorist: Codifying the Passions

Beyond his prolific artistic output and administrative roles, Le Brun made significant contributions as an art theorist. His most famous theoretical work stems from a lecture delivered to the Academy in 1668, titled Conférence sur l'expression générale et particulière (Lecture on General and Specific Expression), though it was only published posthumously in 1698 as Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions (Method for Learning to Draw the Passions).

In this work, Le Brun attempted to create a systematic visual vocabulary for depicting human emotions. Drawing on Cartesian philosophy and physiognomic theories, he argued that each passion (emotion) had a specific physical manifestation, particularly in facial expressions. He provided detailed descriptions and illustrations showing how emotions like joy, sadness, anger, fear, and surprise affected the eyebrows, eyes, mouth, and overall facial musculature. He even extended his analysis to animal expressions, suggesting parallels between human and animal physiognomy.

Le Brun's theory of the passions became highly influential, serving as a standard textbook for academic art training in France and across Europe for over a century. It provided artists with a seemingly rational and teachable method for conveying complex psychological states, essential for the narrative clarity demanded by history painting. While later criticized for being overly schematic and rigid, it represents a significant attempt to apply scientific principles to artistic practice and underscores Le Brun's commitment to the intellectual foundations of art.

Artistic Style: The French Grand Manner

Charles Le Brun's style is often described as the epitome of the French "Grand Manner" or the "Louis XIV style." It represents a synthesis of Italian Baroque grandeur and French classical restraint. From the Baroque, he took the love of drama, dynamic movement, rich color, large scale, and the integration of painting, sculpture, and architecture (Gesamtkunstwerk). From Poussin and classicism, he adopted principles of order, balance, clarity, idealized forms, noble subject matter drawn from history, mythology, or religion, and an emphasis on drawing and composition.

His works are characterized by meticulous planning, complex multi-figure compositions, careful anatomical rendering, and expressive, often theatrical, gestures and facial expressions informed by his theories on the passions. While capable of rich color effects, his palette is often controlled, and line remains fundamental to his definition of form. His art consistently served the purpose of glorifying the King and the state, conveying messages of power, order, and cultural supremacy. Key contemporaries working within or reacting to this milieu included painters like Philippe de Champaigne, known for his austere portraits and religious works, and Pierre Mignard, Le Brun's chief rival.

Rivals, Followers, and Later Years

Despite his dominance, Le Brun faced rivalry, most notably from Pierre Mignard. Mignard, who had also spent considerable time in Rome, cultivated his own network of patrons and represented a slightly softer, more colorist alternative to Le Brun's disciplined style. While Le Brun held sway under Colbert's protection, Mignard gained favor after Colbert's death in 1683. The new Superintendent of Buildings, the Marquis de Louvois, was less supportive of Le Brun, and Mignard eventually succeeded Le Brun as First Painter and Director of the Academy upon Le Brun's death.

Le Brun trained or influenced numerous artists through the Academy and the Gobelins. Figures like Jean Berain the Elder, who became a leading designer in the later Baroque and early Rococo periods, absorbed elements of his style. However, the generation following Le Brun, including artists like Antoine Coypel, Charles de La Fosse, and Jean Jouvenet, began to move towards a lighter, more color-oriented style, influenced by Rubens and Venetian painting, signaling a shift away from Le Brun's strict classicism. This trend would eventually lead to the Rococo style under artists like François Lemoyne and Jean-François de Troy in the early 18th century.

In his later years, with his influence at court waning after Colbert's death, Le Brun increasingly turned to religious painting, producing works characterized by sincere piety and emotional depth. He fell ill in early 1690 and died in Paris on February 12, 1690, at his residence in the Gobelins manufactory.

Legacy and Conclusion

Charles Le Brun's legacy is immense and multifaceted. For nearly three decades, he was the central figure in French art, defining the visual identity of the era of Louis XIV. Through his roles as First Painter, Director of the Academy, and Director of the Gobelins, he exerted unparalleled control over artistic production and education. He masterminded the decorative schemes for the most important royal projects, most notably Versailles, creating enduring symbols of absolute monarchy.

His codification of the passions and his promotion of a classically inspired, yet grandly Baroque, style established the foundations of French academic art for generations. While his reputation suffered somewhat during the French Revolution, which reacted against symbols of the monarchy, and later with the rise of Romanticism and Modernism, the 20th century saw a renewed appreciation for his artistic skill, administrative genius, and historical importance. Artists like Hyacinthe Rigaud and Nicolas de Largillière, famed portraitists of the next generation, built upon the foundations laid during Le Brun's era.

Charles Le Brun remains a pivotal figure, not just as a painter but as the architect of a comprehensive artistic system designed to project the power and glory of the French state. His work at Versailles, the History of Alexander, and his theoretical writings stand as testaments to his ambition, talent, and profound impact on the course of Western art. He truly embodied the spirit of the Grand Siècle, an era when art and power were inextricably intertwined.