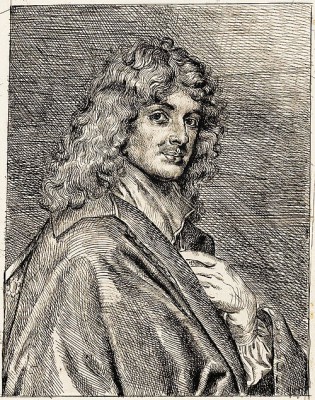

The 17th century in France, often referred to as the Grand Siècle or "Great Century," was a period of extraordinary artistic and cultural efflorescence, largely flourishing under the long and influential reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King. Within this vibrant milieu, portraiture achieved new heights of sophistication and psychological depth, serving not only to record likenesses but also to convey status, power, and character. Among the distinguished painters who specialized in this genre, Claude Lefebvre (1632-1675) carved out a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, niche. Though his career was relatively short, Lefebvre's keen eye for detail, his refined technique, and his ability to capture the essence of his sitters place him firmly within the important lineage of French classical portraiture.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Fontainebleau and Paris

Claude Lefebvre was born in Fontainebleau in 1632, a town renowned for its royal château and the artistic innovations of the School of Fontainebleau that had flourished there in the preceding century under artists like Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio. This artistic heritage likely provided an inspiring backdrop for the young Lefebvre. His initial artistic training came from his father, Jean Lefebvre, who was himself a painter. This familial introduction to the craft was a common path for many artists of the era. He further honed his skills under the tutelage of Claude Dhoey, another local artist in Fontainebleau.

The artistic environment of Fontainebleau, even in the 17th century, still resonated with the elegance and sophistication of its earlier artistic movements. While the Mannerist style of the first School of Fontainebleau had largely given way to newer trends, the emphasis on refined drawing and elegant composition would have been part of the local artistic consciousness. Lefebvre's early education in this setting would have provided him with a solid foundation in the fundamentals of painting.

Seeking broader opportunities and more advanced instruction, Lefebvre, like many aspiring artists, made his way to Paris. The capital was the undisputed center of artistic activity in France, particularly with the establishment of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1648. In Paris, Lefebvre frequented the studios of two prominent masters: Eustache Le Sueur and Charles Le Brun. Le Sueur (1616-1655) was one of the founders of the Académie and a leading figure of French Classicism, known for his serene and graceful religious and mythological compositions, often drawing inspiration from Raphael. His style emphasized clarity, harmony, and a restrained emotionality.

Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) was, arguably, the most powerful and influential artist in France during the reign of Louis XIV. As Premier Peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King) and director of the Gobelins Manufactory and the Académie, Le Brun effectively dictated artistic taste and production for a significant period. His grand, often allegorical, style, exemplified in his decorations for the Palace of Versailles, such as the Hall of Mirrors, defined the official art of the era. Lefebvre not only learned from Le Brun but also reportedly participated in the execution of figures in some of Le Brun's large-scale commissions. This experience would have been invaluable, exposing him to the demands of major state-sponsored art and the techniques required for grand manner painting.

The Parisian Art World and the Rise of a Portraitist

The Paris that Lefebvre entered was a city buzzing with artistic energy, driven by royal and aristocratic patronage. The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture played a crucial role in shaping artistic careers. Membership offered prestige, access to commissions, and the opportunity to exhibit at the Salons. The Académie promoted a hierarchical view of genres, with history painting (religious, mythological, or historical subjects) at the apex, followed by portraiture, genre scenes, landscape, and still life.

Charles Le Brun's dominance at the Académie and in royal circles meant that his classical, often heroic, style was the prevailing standard. Artists like Pierre Mignard (1612-1695), Le Brun's main rival, offered a slightly softer, more decorative alternative, particularly in portraiture, and also enjoyed considerable success. The artistic landscape also included figures like Philippe de Champaigne (1602-1674), a Flemish-born painter who became one of France's leading portraitists, known for his austere, psychologically penetrating depictions, often influenced by Jansenist piety. His nephew, Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne (1631-1681), a contemporary of Lefebvre, also became a respected painter and member of the Académie.

It was within this competitive and highly structured art world that Lefebvre began to forge his career. According to historical accounts, he initially explored religious painting, a genre highly esteemed by the Académie. However, he soon found his true calling in portraiture. This shift may have been pragmatic, as there was a consistent demand for portraits from the nobility, wealthy bourgeoisie, and prominent figures in the court and government. It may also have been a reflection of his particular talents for capturing individual likeness and character.

In developing his portrait style, Lefebvre is said to have first emulated the manner of Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne, whose work was characterized by a sober realism and a focus on the sitter's inner life, much like his more famous uncle. Subsequently, the influence of Charles Le Brun became more apparent in Lefebvre's work, particularly in the dignified presentation of his sitters and the incorporation of elements that conveyed their status and importance. Lefebvre successfully synthesized these influences, developing a style that was both truthful and elegant, capable of satisfying the era's demand for portraits that were both accurate representations and flattering statements of social standing.

Masterpiece: The Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Claude Lefebvre's reputation as a skilled portraitist is perhaps best exemplified by his magnificent Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, painted around 1662 and exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1666. Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) was one of the most powerful men in France, serving as Louis XIV's Minister of Finances and a key architect of French mercantilism and cultural policy. He was also instrumental in the organization of the royal academies, including the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. A portrait of such an influential figure was a significant commission, and Lefebvre rose to the occasion.

The painting, now housed in the Palace of Versailles, depicts Colbert seated, exuding an aura of calm authority and intellectual prowess. He is dressed in sober but rich black attire, his hand resting on a table laden with documents, symbolizing his administrative duties. Behind him, a glimpse of a library or study suggests his scholarly pursuits and the intellectual foundations of his policies. Lefebvre masterfully renders the textures of Colbert's garments, the sheen of his hair, and the thoughtful, discerning expression on his face.

The composition is carefully constructed to emphasize Colbert's status and intellect. The minister is shown three-quarter length, a common format for official portraits. The lighting focuses on his face and hands, drawing the viewer's attention to his intelligent gaze and the instruments of his power – the papers and books. Lefebvre avoids excessive ostentation, reflecting Colbert's own reputation for diligence and seriousness. Yet, the portrait is undeniably grand, conveying the sitter's importance through subtle means: the quality of the painting, the dignified pose, and the carefully chosen attributes. The work demonstrates Lefebvre's ability to combine meticulous detail with a broader sense of character and presence, a hallmark of successful 17th-century portraiture. This painting cemented Lefebvre's reputation and remains his most celebrated work.

Other Notable Works and Stylistic Characteristics

While the Colbert portrait is his most famous, Claude Lefebvre produced a significant body of work during his relatively brief career. He was sought after by prominent members of French society. Among his other known sitters were members of the royal family and high nobility, including a portrait of the Duchess of Orleans (Henrietta of England, first wife of Louis XIV's brother Philippe I, Duke of Orléans) and reportedly a portrait of Charles II of England, though the latter's current whereabouts or definitive attribution can be debated. He also painted a notable portrait of Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, Marquise de Sévigné, the famous letter-writer, around 1665, which is now in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. This work captures the intelligence and vivacity for which Madame de Sévigné was known.

Lefebvre's style is characterized by several key features. His draftsmanship was precise, allowing him to capture likenesses with accuracy. He paid considerable attention to the rendering of details, particularly in clothing, accessories, and the textures of fabrics like silk, velvet, and lace. This meticulousness, possibly influenced by the Netherlandish tradition which had a strong impact on French portraiture through artists like Philippe de Champaigne, added to the realism and richness of his paintings.

His brushwork, often described as delicate, allowed for smooth transitions and a polished finish, which was highly valued in the academic tradition. While adhering to the formal conventions of portraiture of the time – often depicting sitters in dignified poses with attributes related to their profession or status – Lefebvre managed to imbue his subjects with a sense of individuality and psychological presence. His portraits were not mere records of features but attempts to convey something of the sitter's personality or public persona.

The influence of Charles Le Brun can be seen in the often formal and stately compositions, designed to project an image of authority and importance. However, Lefebvre generally avoided the overt allegorical or mythological embellishments that characterized some of Le Brun's grander state portraits. His focus remained more directly on the individual, albeit an individual presented within the context of their social standing. His color palettes were typically rich but controlled, often favoring deep blacks, reds, and browns, which provided a sophisticated backdrop for the flesh tones and highlights on fabrics.

Contemporaries and the Broader Artistic Context

To fully appreciate Claude Lefebvre's contribution, it is essential to view him within the context of his contemporaries and the prevailing artistic currents. The French art scene of the mid-17th century was rich and varied, despite the centralizing influence of the Académie and Le Brun.

Philippe de Champaigne remained a towering figure in portraiture throughout much of Lefebvre's active period. His portraits, such as the iconic depiction of Cardinal Richelieu or his deeply personal Ex-Voto de 1662 (Musée du Louvre), set a standard for psychological depth and sober realism. While Lefebvre's style was perhaps less austere than Champaigne's, the older master's emphasis on capturing the inner character of the sitter was an influential precedent.

Pierre Mignard, Le Brun's great rival, offered a more overtly charming and decorative style of portraiture. Mignard's portraits, often of court ladies, were known for their elegance, flattering portrayals, and rich use of color. He enjoyed immense popularity and eventually succeeded Le Brun as Premier Peintre du Roi after Le Brun's death. Lefebvre's work generally occupied a space between the gravitas of Champaigne and the more overt charm of Mignard, balancing dignity with a refined aesthetic.

Other notable portraitists of the period included Sébastien Bourdon (1616-1671), a versatile artist who also painted religious and mythological scenes, and whose portraits were known for their sensitivity. Laurent de La Hyre (1606-1656), though dying relatively early in Lefebvre's career, was a key figure in Parisian classicism, producing elegant and refined works, including portraits.

The influence of Flemish portraiture, particularly the work of Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), was pervasive throughout Europe. Van Dyck's elegant and aristocratic style of court portraiture had set a new standard, and its echoes could be seen in the work of many French painters, including Lefebvre, in the sophisticated rendering of fabrics and the graceful posing of sitters.

Italian art also continued to be a major source of inspiration. The classical tradition, as revived by Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) and his followers, and the more severe classicism of Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) – a Frenchman who spent most of his career in Rome but whose influence on French art was profound – provided the theoretical and stylistic underpinnings for much of academic painting in France. Lefebvre's training and his association with Le Sueur and Le Brun would have steeped him in these classical principles.

Later in the century, artists like Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743) and Nicolas de Largillière (1656-1746) would take French Baroque portraiture to new heights of grandeur and dynamism, building upon the foundations laid by earlier generations, including painters like Lefebvre. Rigaud's famous state portrait of Louis XIV (1701, Musée du Louvre) is a quintessential example of this later development.

Lefebvre's specific niche was in creating portraits that were both formally accomplished and psychologically astute, appealing to a clientele that valued both accurate representation and dignified presentation. He navigated the expectations of the Académie and the demands of his patrons with considerable skill.

Artistic Legacy and Historical Significance

Claude Lefebvre died in Paris in 1675, at the relatively young age of 43. His career, though impactful, was thus cut short. Despite this, he left a discernible mark on French portraiture of the 17th century. His works are held in major collections, including the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the Palace of Versailles, attesting to his historical importance.

His primary legacy lies in his contribution to the tradition of French classical portraiture. He successfully blended the meticulous realism that had roots in Northern European art with the dignity and formal elegance favored by the French Academy. His ability to capture not just the physical likeness but also the social standing and, to a degree, the personality of his sitters, made him a sought-after artist in his time.

While he may not have achieved the overarching fame of a Le Brun or a Mignard, or the later iconic status of a Rigaud, Lefebvre was a highly competent and respected master within his specialization. He represents a crucial link in the development of French portraiture, demonstrating how artists absorbed and synthesized various influences – from their direct teachers to broader European trends – to create works that resonated with the tastes and values of their era.

Art historians recognize Lefebvre for his technical skill, particularly his refined brushwork and his attention to detail. His portrait of Colbert, in particular, is frequently cited as a prime example of 17th-century French official portraiture, effectively conveying the power and intellect of one of the era's most significant figures. His work provides valuable visual documentation of the personalities who shaped the Grand Siècle.

In the broader narrative of art history, Claude Lefebvre stands as a testament to the depth of talent present in 17th-century France. He was an artist who, within the established conventions of his time, produced works of lasting quality and historical interest. His portraits offer a window into the world of Louis XIV's France, reflecting its hierarchies, its personalities, and its refined aesthetic sensibilities. Though his life was short, his art endures as a significant contribution to the rich tapestry of the French Grand Siècle.