Charles-Louis Clérisseau stands as a pivotal figure in the transition of European art and architecture towards Neoclassicism in the 18th century. Born in Paris on August 28, 1721, and living to the remarkable age of 98, passing away in the Parisian suburb of Auteuil on January 9, 1820, Clérisseau's career spanned a period of profound artistic and intellectual transformation. He was not merely an architect but also an accomplished painter, particularly in watercolor, a meticulous draughtsman, and an influential antiquarian. His profound engagement with the ruins of antiquity, especially those of Rome, provided a crucial visual and intellectual foundation for the Neoclassical movement, influencing patrons and fellow artists across Europe and even in the nascent United States.

Early Life and Academic Foundations in Paris

Clérisseau's artistic journey began in his native Paris, the vibrant heart of European culture. He received his formal architectural training under the esteemed Germain Boffrand (1667-1754), a prominent architect whose work, while rooted in the French Classical tradition, also showed elements of the Rococo style that was then fashionable. Boffrand's tutelage would have provided Clérisseau with a strong grounding in architectural principles, design, and draughtsmanship.

The young Clérisseau's talent was undeniable. In 1746, he achieved a significant milestone by winning the prestigious Grand Prix de Rome for architecture, awarded by the Académie Royale d'Architecture. This coveted prize was a gateway for promising French artists and architects, granting them a funded period of study at the French Academy in Rome. This opportunity was transformative, not just for Clérisseau, but for generations of artists who absorbed the lessons of classical antiquity firsthand.

The Roman Sojourn: A Crucible of Influence

Clérisseau's arrival in Rome in the late 1740s placed him at the epicenter of a burgeoning fascination with classical antiquity. The city was a living museum, its ancient ruins serving as powerful reminders of a glorious past. It was here that Clérisseau's artistic identity truly began to form, shaped by the environment and the remarkable individuals he encountered.

Mentorship and Artistic Development in Rome

In Rome, Clérisseau further honed his skills, particularly in painting. He studied under Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), one of the foremost painters of vedute (view paintings) and architectural capriccios. Panini was renowned for his depictions of Roman ruins and contemporary Roman festivals, often imbued with a sense of grandeur and picturesque decay. Under Panini's guidance, Clérisseau mastered the art of watercolor, a medium perfectly suited for capturing the subtle light and atmospheric effects of the Roman landscape and its ancient structures. He developed a distinctive style characterized by precise rendering, delicate coloration, and an ability to evoke both the archaeological accuracy and the romantic allure of the ruins.

His dedication to depicting ancient Roman architectural remains was intense. He produced numerous highly finished drawings and watercolors, not only of famous monuments but also of lesser-known fragments, interiors, and decorative details. These works were more than mere topographical records; they were artistic interpretations that conveyed a deep understanding and appreciation of classical forms.

Forging Key Relationships

Rome in the mid-18th century was a cosmopolitan hub, attracting artists, architects, scholars, and Grand Tourists from across Europe. Clérisseau thrived in this environment, establishing connections that would prove crucial to his career and the dissemination of his ideas.

Among his most significant acquaintances was Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), the Venetian architect and printmaker whose dramatic and often fantastical etchings of Roman antiquities, such as his "Vedute di Roma" and "Carceri d'Invenzione" (Imaginary Prisons), had a profound impact on the European imagination. While Piranesi's vision was often more grandiose and sublime, Clérisseau shared his passion for Roman archaeology and his desire to document and interpret its remains. They were part of a circle of artists who were redefining the way antiquity was perceived, moving beyond a purely academic interest to a more emotional and aesthetic engagement.

Clérisseau also formed a close association with the French landscape painter Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714-1789). Vernet, known for his seascapes and landscapes often incorporating classical elements, was another prominent figure in the Roman art scene. Together with Piranesi and Vernet, Clérisseau undertook sketching expeditions, notably to Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli in 1752, a site rich in architectural inspiration. These collaborations and shared explorations undoubtedly enriched his understanding and artistic vocabulary.

Another pivotal relationship was with the Scottish architect Robert Adam (1728-1792). Adam arrived in Rome in 1755 and quickly recognized Clérisseau's expertise. Clérisseau became Adam's mentor and drawing master, accompanying him on tours of ancient sites and instructing him in the art of archaeological drawing. This partnership would lead to one of Clérisseau's most significant contributions to architectural history.

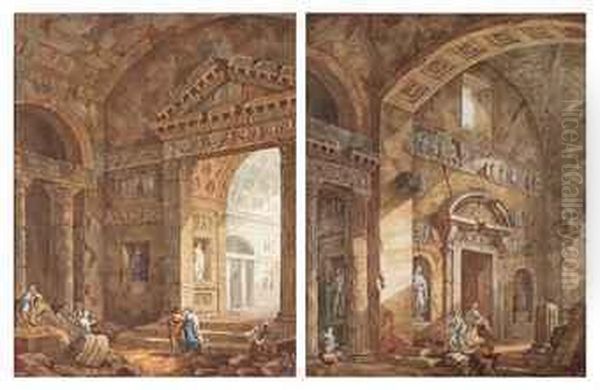

Hubert Robert (1733-1808), often dubbed "Robert des Ruines," was another French painter with whom Clérisseau shared a profound interest in the picturesque qualities of ancient ruins. Though Robert arrived in Rome slightly later, their paths and artistic concerns frequently intersected, both contributing to the romantic vision of antiquity that captivated their contemporaries.

The Archaeological Eye: Documenting Ancient Rome

Clérisseau's work in Rome was characterized by a meticulous attention to detail combined with an artistic sensibility. He was not simply a copyist; he was an interpreter. His drawings and watercolors of Roman ruins, such as the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and various temples and baths, were prized for their accuracy and their aesthetic appeal. He often populated his scenes with small figures, adding a sense of scale and life, a technique also employed by Panini and Hubert Robert.

His focus was not limited to the grand, well-known monuments. He delved into the specifics of classical ornamentation, studying friezes, capitals, and stucco work. This deep knowledge of ancient decorative motifs would become a hallmark of his own designs and a valuable resource for other architects seeking to emulate classical styles. His works served as a visual encyclopedia for those who could not visit Rome themselves, playing a crucial role in the dissemination of Neoclassical taste. The precision of his renderings was particularly valued in an era that was increasingly interested in archaeological authenticity, spurred by discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii.

Collaboration with Robert Adam: Spreading Neoclassical Ideals

The collaboration between Clérisseau and Robert Adam culminated in the landmark publication, Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia (1764). Clérisseau accompanied Adam on his expedition to Spalato (modern-day Split, Croatia) in 1757 to survey and draw the remains of Diocletian's Palace. Clérisseau's skill in producing accurate and evocative drawings was indispensable to the project.

The resulting folio, largely illustrated with engravings made from Clérisseau's drawings, was a triumph. It provided architects with a detailed record of a major Roman imperial palace, showcasing a range of architectural forms and decorative elements that were less familiar than those in Rome itself. The publication was highly influential, contributing significantly to the Adam brothers' reputation and providing a rich source of inspiration for Neoclassical architects across Britain and beyond. It demonstrated a rigorous approach to archaeological documentation combined with high artistic quality, setting a new standard for such publications. This project solidified Clérisseau's reputation as a leading authority on ancient architecture.

Clérisseau's Artistic Style: Precision and Imagination

Clérisseau's artistic style is firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, yet it possesses a unique blend of archaeological precision and romantic imagination. His training under Panini is evident in his mastery of perspective and his ability to create convincing architectural spaces. However, Clérisseau's work often displays a more delicate touch and a softer palette than Panini's more robust oils.

His preferred medium for depicting ruins was watercolor and gouache over pen and ink. This allowed him to capture the texture of weathered stone, the play of light and shadow, and the subtle colors of ancient frescoes and marbles. His compositions are carefully balanced, often highlighting the grandeur of the ancient structures by contrasting them with the small scale of human figures.

While accuracy was paramount in his archaeological studies, Clérisseau also produced capricci – imaginary architectural scenes that combined real and invented elements. These works allowed him greater freedom of expression, showcasing his inventive powers and his deep immersion in the visual language of antiquity. This blend of the real and the ideal, the documented and the imagined, was characteristic of the more romantic strain of Neoclassicism, a sensibility he shared with artists like Piranesi and Hubert Robert. His influence can be seen in the work of later painters of architectural views, such as Louis-François Cassas (1756-1827).

Patronage and Major Commissions

Clérisseau's expertise and artistic talent attracted a distinguished clientele, including royalty, aristocracy, and influential intellectuals. His ability to translate the spirit of antiquity into contemporary designs made him a sought-after figure.

Imperial Aspirations: Catherine the Great

One of Clérisseau's most notable patrons was Empress Catherine the Great of Russia (1729-1796). An enthusiastic proponent of Neoclassicism, Catherine commissioned Clérisseau in the 1770s to design a triumphal arch and a vast, antique-style palace for her near Moscow. Although the palace was never built, Clérisseau produced an extensive series of drawings for the project, which are now housed in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. These designs, characterized by their grandeur and their sophisticated use of classical motifs, demonstrate his ambitious vision.

Catherine also acquired a significant collection of Clérisseau's drawings of ancient ruins and decorative schemes. His influence extended to the architects working for Catherine in Russia, such as Charles Cameron (c.1745-1812) and Giacomo Quarenghi (1744-1817), who were instrumental in shaping the Neoclassical appearance of St. Petersburg. Clérisseau's role as an artistic advisor and a source of authentic classical models was highly valued by the Empress.

A Transatlantic Legacy: Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia State Capitol

Perhaps Clérisseau's most enduring architectural legacy lies in the United States, through his association with Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). While serving as the American minister to France in the 1780s, Jefferson, an accomplished amateur architect himself, sought Clérisseau's assistance in designing the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond.

Jefferson envisioned a building that would embody the classical ideals of the new republic. He and Clérisseau based their design on the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, an exceptionally well-preserved Roman temple. Clérisseau produced drawings and a plaster model of the proposed building, adapting the ancient temple form to the needs of a modern governmental structure. The Virginia State Capitol, completed in 1788, became a seminal work of American Neoclassicism, influencing the design of countless public buildings in the United States. This collaboration highlights Clérisseau's international reach and his ability to adapt classical principles to new contexts. Jefferson's choice, guided by Clérisseau, signaled a deliberate adoption of Roman republican architectural language for the new American democracy, a preference also seen in the work of sculptors like Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), who famously sculpted Washington.

The Hall of Ruins and Other Decorative Schemes

Clérisseau was also renowned for his interior designs, particularly his "ruin rooms." One of the most famous was the painted room he created in the 1760s for the monastery of Santa Trinità dei Monti in Rome for Father Le Sueur. This room was decorated with frescoes depicting crumbling ancient structures, creating an immersive, illusionistic environment that transported the viewer into a romanticized classical past. This concept of the ruin room became fashionable, and Clérisseau executed similar schemes for other patrons.

Upon his return to Paris, he designed the Neoclassical interiors for the Hôtel Grimod de La Reynière, a prominent Parisian townhouse. These interiors, with their elegant use of classical motifs, arabesques, and grotesques inspired by ancient Roman decoration (such as those found in Nero's Domus Aurea), were highly influential and showcased his mastery of the Neoclassical decorative vocabulary. His work in this area paralleled the efforts of designers like Robert Adam in Britain, who were also creating integrated Neoclassical interiors.

Return to Paris and Later Years

Clérisseau returned to Paris permanently around 1767 or 1768. He was admitted to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1769 as a painter of architectural subjects. He continued to work as an architect, designer, and painter, though perhaps with less prominence in major building projects than some of his contemporaries like Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713-1780), architect of the Panthéon in Paris, or visionary architects like Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799) and Claude Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806), whose Neoclassical designs were often more monumental or radical.

His long life meant he witnessed the entirety of the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the Bourbon Restoration. While the political upheavals undoubtedly affected artistic patronage, Clérisseau's reputation as a master of classical design and a venerable link to the great tradition of Roman study likely ensured him continued respect. He was appointed Architect to the King and later, under Napoleon, he received the Legion of Honour in 1804. His works continued to be collected, and his influence persisted through his former pupils and the dissemination of his drawings.

The later part of his career saw him focus more on publishing his extensive collection of drawings and antiquarian research. His Antiquités de la France, Monumens de Nismes (1778, though only the first part was published then, with a fuller edition in 1804) was another significant contribution, documenting the Roman monuments of Nîmes, including the Maison Carrée that had so inspired Jefferson.

Clérisseau's Enduring Legacy in European Art History

Charles-Louis Clérisseau's position in European art history is that of a crucial catalyst and a defining practitioner of Neoclassicism. His primary contribution lay in his meticulous yet evocative depictions of ancient ruins, which provided an authentic visual vocabulary for the burgeoning Neoclassical movement. He was more than an antiquarian; he was an artist who could translate archaeological knowledge into compelling visual forms and architectural designs.

His influence was widespread. In France, he contributed to the shift away from the Rococo style towards a more sober and classically inspired aesthetic, a trend also championed by figures like the painter Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809), who was a teacher to Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), the leading Neoclassical painter. In Britain, his collaboration with Robert Adam was instrumental in shaping the Adam style. In Russia, his work for Catherine the Great helped to establish Neoclassicism as the imperial style. In the United States, his design for the Virginia State Capitol provided a powerful model for public architecture.

His drawings and watercolors are found in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Sir John Soane's Museum in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. These works continue to be studied for their artistic merit and their historical importance. Sir John Soane (1753-1837) himself, a prominent British Neoclassical architect, was an avid collector of architectural drawings, including those by Clérisseau and Piranesi, recognizing their inspirational value.

Influence on Contemporaries and Successors

Clérisseau's direct influence can be seen in the architects and designers he taught or collaborated with, most notably Robert Adam and Thomas Jefferson. Indirectly, his work resonated with a broad range of artists who shared his passion for antiquity. Painters like Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and Benjamin West (1738-1820), though primarily figure painters, operated within the Neoclassical milieu that Clérisseau helped to define, often incorporating classical settings and themes into their work. Sculptors like Antonio Canova (1757-1822) similarly drew inspiration from the renewed interest in classical forms that Clérisseau's generation championed.

The meticulousness of his archaeological drawings set a standard for architectural representation. His ability to combine this precision with a sense of the picturesque and the sublime ensured that his work appealed to both the scholarly and the aesthetic sensibilities of his time. He helped to create a visual language for Neoclassicism that was both authoritative, grounded in the study of ancient models, and flexible enough to be adapted to a variety of modern purposes, from imperial palaces to republican government buildings.

Conclusion

Charles-Louis Clérisseau was a remarkable figure whose long and productive career bridged the Rococo and Neoclassical eras. As an architect, draughtsman, painter, and antiquarian, he played an indispensable role in the study, interpretation, and dissemination of classical antiquity. His meticulous drawings of Roman ruins, his influential publications, and his architectural designs left an indelible mark on the art and architecture of the 18th and early 19th centuries. From the palaces of Russia to the public buildings of the newly formed United States, Clérisseau's vision of antiquity helped to shape the physical and intellectual landscape of the Western world, securing his place as a key architect of the Neoclassical age. His legacy endures not only in the buildings he designed but also in the countless drawings that continue to inspire awe for the grandeur of the past and admiration for his artistic skill.