Carlo Labruzzi stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of late 18th and early 19th-century Italy. A painter, etcher, and draughtsman, Labruzzi carved a niche for himself primarily through his evocative landscapes and meticulous depictions of classical ruins, activities that placed him at the heart of the Grand Tour phenomenon. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents of his time, the patronage systems that supported artists, and the enduring allure of Italy's classical past.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Rome

Born in Rome in 1748, Carlo Labruzzi's origins were modest. His father was a weaver and velvet tailor, and his mother was Teresa Crettini. While not born into an established artistic dynasty, Rome itself was an unparalleled academy. The city teemed with ancient monuments, Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces, and a thriving contemporary art scene, providing an immersive education for any aspiring artist. It is likely that Labruzzi's initial artistic inclinations were nurtured by this environment, even before formal training commenced.

His younger brother, Pietro Labruzzi (c. 1739–1805), also pursued an artistic career, achieving notable success as a painter and eventually becoming a court painter to King Stanisław August Poniatowski of Poland. This familial connection to the arts may have provided Carlo with early encouragement and perhaps some initial guidance, though Carlo's path would predominantly be rooted in Rome and its environs.

Details of Carlo Labruzzi's earliest formal training are somewhat sparse, but it is known that he spent some time in Nuremberg. However, by around 1780, he had returned to Rome, the city that would become the primary stage for his artistic endeavors. Rome, at this time, was a magnet for artists from across Europe, drawn by its classical heritage and the opportunities for patronage, particularly from the influx of wealthy Grand Tourists.

The Roman Artistic Milieu and Academic Affiliations

Upon his return to Rome, Labruzzi began to integrate himself into the city's artistic institutions. He became a member of the prestigious Congregazione dei Virtuosi al Pantheon, an honorific society of artists and scholars. A more significant milestone was his admission to the Accademia di San Luca. He was first recorded as a member in 1786 and appears again in records for 1796. The Accademia was the preeminent artistic institution in Rome, and membership conferred considerable prestige and professional validation.

The artistic environment in Rome during Labruzzi's active years was rich and varied. Neoclassicism was gaining ascendancy, championed by figures like Anton Raphael Mengs and the archaeologist-theorist Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who urged artists to emulate the "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" of classical art. Alongside this, the tradition of veduta (view painting), popularized earlier in the century by artists like Giovanni Paolo Panini and later, with a more dramatic and archaeological focus, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, continued to flourish. Landscape painting, both idealized and topographical, was also in high demand.

Labruzzi navigated these currents, finding his primary expression in landscape and the depiction of antiquities. He is known to have sought guidance from, or at least shown his work to, established artists in Rome. Among these were Jakob Philipp Hackert, a German landscape painter highly favored by European courts and Grand Tourists for his meticulously detailed and serene Italian views, and Louis Ducros, a Swiss painter renowned for his large-scale, dramatic watercolors of Roman scenes and landscapes, often catering to the British market. Exposure to such successful contemporaries would have undoubtedly informed Labruzzi's own stylistic development and market awareness.

The Enduring Influence of Claude Lorrain

A defining characteristic of Carlo Labruzzi's landscape art was the profound influence of the 17th-century French master Claude Lorrain. Claude, who spent most of his career in Rome, had established a paradigm for idealized landscape painting, characterized by harmonious compositions, soft, atmospheric light (often depicting sunrise or sunset), and the integration of classical or biblical figures into pastoral settings. His work was immensely popular, particularly with British collectors, and his influence resonated through the 18th century and beyond.

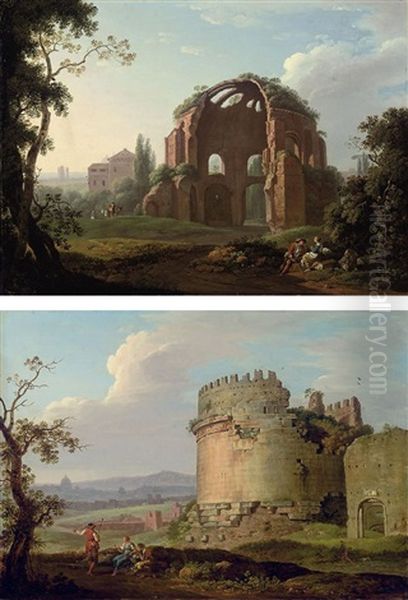

Labruzzi absorbed Claude's lessons, but his interpretation was distinct. While he adopted the Claudian emphasis on light and picturesque composition, Labruzzi's style is often described as lighter in touch and employing softer, more delicate color palettes. His landscapes, whether in oil or watercolor, often possess a fresh, airy quality. He frequently depicted the Roman Campagna, the Alban Hills, and other scenic locales around Rome, imbuing them with a sense of tranquil beauty and timelessness that appealed to the romantic sensibilities of his era. This connection to Claude also resonated strongly with British taste, as Claude Lorrain was a cornerstone of British aristocratic collections, and artists who could evoke his spirit were highly sought after.

The Grand Tour and British Patronage

The phenomenon of the Grand Tour was central to the careers of many artists in Italy during the 18th century, and Labruzzi was no exception. Wealthy young men, predominantly from Britain but also from other parts of Europe, undertook extended travels through Italy to complete their classical education and cultural refinement. Rome was an essential stop, and these travelers were avid consumers of art, commissioning portraits, purchasing views of ancient monuments, and acquiring landscapes as souvenirs and testaments to their sophisticated tastes.

Labruzzi's skill in depicting both the picturesque landscapes and the venerable ruins of Italy made him a popular choice for these patrons. His works served not only as mementos but also as visual records of the sites that had so captivated their imaginations. The British writer and connoisseur Horace Walpole, a key figure in the Gothic Revival and an arbiter of taste, is recorded as having praised Labruzzi's landscapes, noting their "feeling and sensitivity." Such endorsements from influential figures would have significantly boosted his reputation among potential British clients.

His interactions were not limited to patrons; he also engaged with fellow artists catering to the Grand Tour market, such as the British painter Mary Benwell (often cited as Mary Blueberry in some older Italian sources, likely a mistranscription), who was active in Rome. These networks of artists and patrons created a dynamic cultural exchange.

The Pivotal Journey: The Appian Way with Sir Richard Colt Hoare

One of the most significant episodes in Labruzzi's career, and the one for which he is perhaps best remembered, was his collaboration with the British antiquarian, archaeologist, and baronet, Sir Richard Colt Hoare. In 1789, Hoare, a passionate student of classical antiquity, invited Labruzzi to accompany him on an ambitious journey along the ancient Via Appia, the "Regina Viarum" (Queen of Roads), from Rome towards Benevento and ultimately Brindisi. The purpose was to meticulously document the surviving tombs, villas, and other ancient structures along this historic route.

Labruzzi's role was to create a visual record through sketches and watercolors. This undertaking was a quintessential Grand Tour project, combining scholarly antiquarian interest with the appreciation of picturesque scenery. The journey, however, proved arduous. They were beset by bad weather and Labruzzi himself suffered from bouts of illness, possibly malaria, which was prevalent in the marshy areas of the Campagna. These challenges eventually forced them to curtail their original plan, and they did not complete the entire route to Brindisi.

Despite these difficulties, Labruzzi produced a remarkable series of 226 sepia wash drawings. These works are characterized by their topographical accuracy, capturing the specific details of the ruins, yet they are also imbued with a romantic sensibility, often depicting the monuments in their overgrown, melancholic state. The drawings convey the grandeur of the ancient world and its gradual decay, themes that resonated deeply with the Neoclassical and burgeoning Romantic imagination.

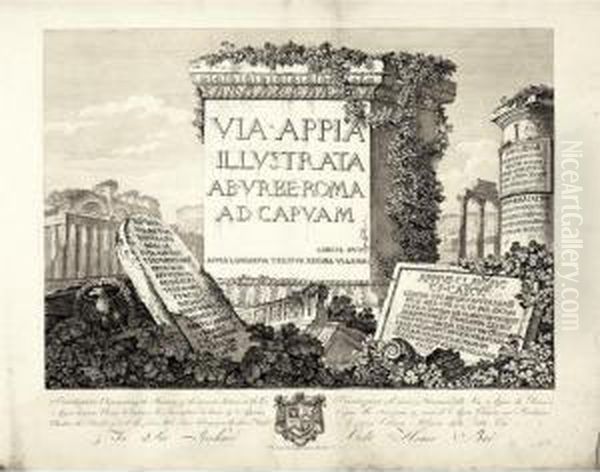

Sir Richard Colt Hoare later arranged for a selection of these drawings to be engraved and published. Twenty-four plates were issued in 1794 under the title Via Appia Illustrata ab Urbe Roma ad Capuam. A more extensive, though still incomplete, set of etchings by Labruzzi himself, based on these drawings, was also produced, with some sources indicating a series of 48 plates. The original drawings remained in Hoare's collection at Stourhead in Wiltshire and are now dispersed, with significant holdings in institutions like the British Museum and the Vatican Library. This project cemented Labruzzi's reputation as a skilled topographical artist and a chronicler of antiquity.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Versatility

Carlo Labruzzi was proficient in several media. His oil paintings, often landscapes, showcase his Claudian affinities with their balanced compositions and attention to atmospheric effects. However, he was particularly adept with watercolor and sepia wash, media well-suited to the demands of topographical work and the creation of luminous, delicate effects. His drawings and watercolors from the Appian Way series are prime examples of his skill in capturing both precise detail and evocative mood.

His landscape style, while influenced by Claude, also shows an awareness of other contemporary landscape painters. One might see parallels with the work of Richard Wilson, the Welsh painter who spent considerable time in Italy and was instrumental in developing the classical landscape tradition in Britain. Wilson, like Labruzzi, was adept at capturing the specific character of the Italian countryside while imbuing it with a sense of classical order.

Beyond landscapes and antiquities, Labruzzi demonstrated considerable versatility. He was a capable portrait painter, a genre much in demand by Grand Tourists wishing to have their likenesses captured against a Roman backdrop, a tradition famously dominated by artists like Pompeo Batoni. Labruzzi also undertook commissions for religious works and altarpieces. For instance, he painted an Apollo and Diana for Prince Borghese, a prominent Roman noble family, indicating his acceptance into high levels of patronage. He is also credited with altarpieces and other religious subjects for churches, demonstrating his ability to work within traditional iconographic frameworks.

His skill as an etcher was also significant. The etchings for the Via Appia Illustrata and other independent prints allowed his work to reach a wider audience. The print market was crucial for disseminating artistic ideas and images, and artists like Piranesi had demonstrated the power and profitability of architectural and antiquarian prints. Labruzzi's etchings, while perhaps not possessing the dramatic intensity of Piranesi's Carceri or his grand views of Rome, are valued for their clarity and fidelity to the subjects.

Academic Recognition and Later Career in Perugia

Labruzzi's artistic achievements and his standing within the Roman art world were recognized through various appointments. His membership in the Accademia di San Luca was a clear mark of distinction. Later in his career, his reputation extended beyond Rome. In 1814, he was appointed Director of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Perugia, a significant position that involved overseeing the artistic education and direction of the institution in this important Umbrian city. He held this post for three years, until his death.

This move to Perugia in his later years suggests a respected elder statesman status within the Italian art community. Perugia, with its own rich artistic heritage, would have provided a different, perhaps quieter, environment than the bustling international hub of Rome. His role as director would have involved teaching and administration, passing on his knowledge and experience to a new generation of artists.

Challenges and the Artist's Life

The anecdote of the challenging journey along the Appian Way with Sir Richard Colt Hoare highlights the practical difficulties faced by artists, particularly those engaged in fieldwork. Travel in the 18th century could be uncomfortable and dangerous. Illness was a constant threat, and weather could disrupt plans and damage materials. Labruzzi's perseverance in producing over two hundred drawings under such conditions speaks to his dedication and resilience.

Like many artists, Labruzzi would have navigated the complexities of patronage, seeking commissions, and managing his reputation. The art market in Rome was competitive, with numerous Italian and foreign artists vying for the attention of wealthy patrons. Success depended not only on talent but also on social skills, connections, and an understanding of prevailing tastes.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Carlo Labruzzi died in Perugia in 1817, at the age of 69. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be valued by collectors and institutions. His paintings, drawings, and prints are found in numerous public and private collections, including the Vatican Library, the British Museum, the National Gallery in London, and various Italian museums.

His most enduring legacy is perhaps his contribution to the visual record of Roman antiquity, particularly the Appian Way series. These works provide invaluable documentation of monuments, some of which may have since deteriorated or been altered. They capture a specific moment in the perception of the classical past, viewed through the lens of late 18th-century sensibility.

In the broader history of landscape painting, Labruzzi represents a continuation and adaptation of the Claudian tradition, infusing it with a freshness and delicacy that appealed to his contemporaries. His work, particularly through its dissemination in Britain via patrons like Hoare, contributed to the ongoing British love affair with Italian scenery and classical ruins. While he may not have achieved the towering fame of a Piranesi or a Canaletto (whose Venetian vedute set a standard for topographical painting), Labruzzi's art holds a distinct and honorable place.

His influence can be seen as part of the wider current that fed into 19th-century Romanticism and Naturalism. The detailed observation in his topographical work, combined with the evocative mood of his landscapes, prefigures aspects of later landscape painting. Artists like J.M.W. Turner, who himself was deeply influenced by Claude Lorrain and made extensive tours of Italy, would have been aware of the tradition of depicting Italian landscape and antiquities to which Labruzzi contributed. Even the more domestically focused landscapes of John Constable share a heritage in the careful observation of nature that was being honed by artists like Labruzzi in different contexts. The earlier, wilder landscapes of Salvator Rosa also formed part of the Italian landscape tradition that artists like Labruzzi would have been aware of, providing a contrasting, more untamed vision to Claude's serenity. Similarly, the work of French landscape artists active in Italy, such as Hubert Robert, known for his picturesque depictions of ruins, formed part of this international artistic dialogue in Rome.

Conclusion: A Dedicated Chronicler of Beauty and Time

Carlo Labruzzi was an artist deeply attuned to the beauty of the Italian landscape and the profound resonance of its ancient past. Working within the established traditions of his time, he nevertheless developed a personal style characterized by sensitivity, skill, and a keen observational eye. His collaboration with Sir Richard Colt Hoare on the Appian Way project remains a landmark in antiquarian documentation and picturesque travel. As a painter, etcher, and influential academician, Labruzzi contributed significantly to the artistic culture of Rome and Perugia. His works continue to offer delight to viewers and valuable insights for historians, ensuring his place as a respected master of his era, a dedicated chronicler of beauty, and a witness to the passage of time across the Roman Campagna.