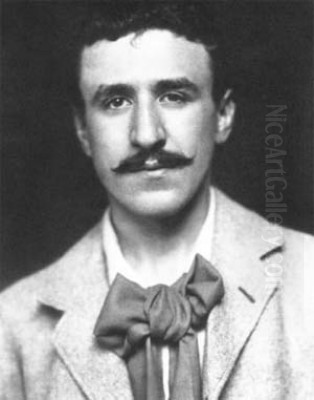

Charles Rennie Mackintosh stands as a colossus in the annals of art and architectural history, a figure whose innovative spirit and distinctive aesthetic bridged the 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement with the burgeoning ideals of 20th-century Modernism. Born in Glasgow on June 7, 1868, and passing away in London on December 10, 1928, Mackintosh was not merely an architect but a consummate designer, painter, and artist. His work, deeply rooted in his Scottish heritage yet profoundly international in its outlook and influence, continues to inspire and captivate audiences worldwide. His holistic approach to design, where every element of a building, from its structure to its furnishings and decorative details, was conceived as part of a unified whole, marked him as a pioneer.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Charles Rennie McIntosh (he would later alter the spelling of his surname) was the fourth of eleven children born to William McIntosh, a police superintendent, and Margaret Rennie. His early years in Glasgow, a city at the zenith of its industrial power, undoubtedly shaped his understanding of materials and construction. However, it was also a city grappling with the social and aesthetic consequences of rapid industrialization, a context that fueled many artistic reform movements of the era.

From a young age, Mackintosh displayed a keen interest in drawing and nature. Anecdotal evidence suggests he suffered from a limp due to a contracted tendon in one foot and had issues with his eyesight, including a droop in his right eyelid. Some biographers speculate these physical challenges might have contributed to his introspective nature and intense focus on his artistic pursuits. His early education included time at Reid's Public School and Allan Glen's High School.

His formal artistic training began in 1883 when he enrolled as an evening student at the Glasgow School of Art, a pivotal institution in his life and career. Concurrently, in 1884, he was apprenticed to a local architect, John Hutchison. This dual engagement provided him with both theoretical artistic grounding and practical architectural experience. At the Glasgow School of Art, he thrived under the progressive leadership of its director, Francis Newbery, who championed new ideas and encouraged students to develop individual styles. Newbery was a significant mentor and lifelong supporter of Mackintosh.

The Honeyman and Keppie Years and Early Recognition

In 1889, Mackintosh joined the architectural practice of Honeyman and Keppie as a draughtsman. John Honeyman was an established architect, and John Keppie, a younger partner, had also attended the Glasgow School of Art. It was within this firm that Mackintosh would develop his architectural skills and begin to make his mark. His talent was quickly recognized, and he won several student prizes, including the prestigious Alexander Thomson Travelling Studentship in 1890 for the "Public Hall."

The £60 prize from the Alexander Thomson scholarship enabled him to embark on an architectural tour of Italy in 1891. This journey exposed him to the masterpieces of classical and Renaissance architecture, but rather than merely emulating these historical styles, Mackintosh absorbed lessons in form, massing, and the use of light, which he would later synthesize into his own unique vocabulary. His Italian sketchbooks are filled with meticulous drawings not only of buildings but also of natural forms, particularly plants, revealing his enduring fascination with the organic world.

Upon his return, he resumed his work at Honeyman and Keppie and continued his studies at the Glasgow School of Art. It was during this period, in the early 1890s, that he began to develop his distinctive linear style, characterized by elongated forms, subtle curves, and a restrained use of ornament, often inspired by botanical motifs.

The Glasgow Four: A Creative Alliance

A crucial development in Mackintosh's artistic journey was his association with a group of like-minded artists at the Glasgow School of Art. He, along with his friend and fellow apprentice at Honeyman and Keppie, James Herbert MacNair, and two sisters, Margaret Macdonald and Frances Macdonald, formed an informal alliance that came to be known as "The Four," or sometimes "The Spook School" due to the ethereal, often unsettling, nature of their early symbolist works.

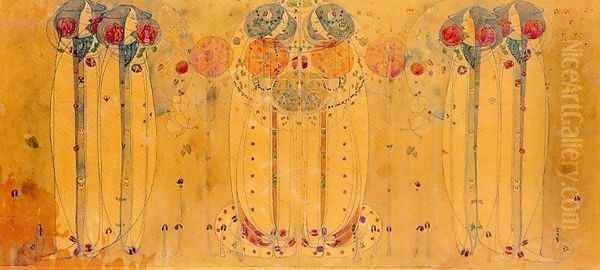

Margaret Macdonald, whom Mackintosh would marry in 1900, became his most important collaborator and a significant artistic influence. Her own work, characterized by flowing lines, mystical figures, and decorative gesso panels, complemented and enriched Mackintosh's more architectural designs. Frances Macdonald, who later married MacNair, also contributed significantly to the group's output. Together, "The Four" developed a distinctive visual language that blended Celtic revivalism, Japanese aesthetics, Symbolism, and the emerging principles of Art Nouveau.

Their collaborative efforts extended beyond painting and graphic design to include furniture, metalwork, and textiles. They exhibited their work in Glasgow, London, and importantly, on the continent, where their innovative style garnered considerable attention and acclaim, often more so than in their native Scotland initially. Their distinctive approach became a cornerstone of what was internationally recognized as the "Glasgow Style," a unique Scottish variant of Art Nouveau.

Architectural Masterpieces: Defining a New Language

Mackintosh's architectural career, though relatively short and largely confined to Glasgow and its environs, produced a series of buildings that are now considered landmarks of early modern architecture. He became a partner in Honeyman and Keppie in 1901, the firm eventually becoming Honeyman, Keppie & Mackintosh in 1904.

The Glasgow School of Art

Undoubtedly his magnum opus, the Glasgow School of Art building (designed 1896-1899, built in two phases 1897-1899 and 1907-1909) is a testament to Mackintosh's genius. The commission was won in competition, and its design was revolutionary for its time. The building masterfully combines traditional Scottish baronial forms with a modern sensibility. The north facade, with its massive studio windows, is a powerful statement of functionalism, while the later west wing, featuring the iconic library with its soaring vertical timbers and intricate play of light and shadow, is a tour de force of spatial design. The building suffered two devastating fires, in 2014 and 2018, tragically damaging much of his original vision, though efforts for its faithful restoration continue.

Queen's Cross Church

Designed in 1896 and completed in 1899, Queen's Cross Church in Maryhill, Glasgow, is Mackintosh's only completed church. It showcases his ability to create a spiritually uplifting space through simple forms, subtle detailing, and a masterful control of light. The design features a wide nave, a distinctive tower, and stylised floral motifs carved in stone and wood, including his famous "Mackintosh Rose." The influence of Gothic architecture is discernible, but reinterpreted through his unique lens.

Scotland Street School

Commissioned by the Glasgow School Board in 1903 and completed in 1906, Scotland Street School (often referred to in initial documentation as Martyrs' Public School or connected to the Ruchill Street Church Halls project in terms of timeline and client type) demonstrates Mackintosh's approach to a utilitarian building type. He elevated the school's design beyond mere functionality, incorporating striking twin cylindrical towers with conical roofs for the stairwells, large windows for ample light, and thoughtful interior detailing. The building reflects his concern for the well-being and inspiration of the children who would use it.

The Hill House, Helensburgh

Designed between 1902 and 1904 for the publisher Walter Blackie, The Hill House in Helensburgh is one of Mackintosh's most important domestic commissions. It is a prime example of his "total design" philosophy. Mackintosh, along with Margaret Macdonald, designed not only the building itself but also its interiors, furniture, textiles, and even garden layout. The exterior is a striking composition of asymmetrical masses, rendered in traditional Scottish harling, while the interiors are a harmonious blend of light and dark spaces, with carefully chosen colours and exquisite, often symbolic, decorative details. The house is a deeply personal and artistic statement, reflecting the personalities of both the clients and the architect.

Willow Tea Rooms

Between 1896 and 1917, Mackintosh undertook several commissions for Catherine Cranston, a Glasgow businesswoman who was a key patron of modern design. The Willow Tea Rooms on Sauchiehall Street (1903) are the most famous of these. Mackintosh was given a free hand to design the entire building, from the facade to the interiors of various tea rooms, including the elegant "Room de Luxe." Here, his collaboration with Margaret Macdonald was particularly fruitful, with her gesso panels and decorative schemes contributing significantly to the ethereal and sophisticated atmosphere. The high-backed chairs, geometric patterns, and use of coloured glass are iconic elements of this project.

Interior and Furniture Design: The Total Work of Art

Mackintosh's belief in the "Gesamtkunstwerk," or total work of art, meant that his architectural vision extended seamlessly into the design of interiors and their contents. His furniture is highly distinctive, characterized by attenuated proportions, strong vertical lines, and a restrained palette, often ebonized wood contrasted with light upholstery or inlaid with mother-of-pearl, metal, or coloured glass.

His high-backed chairs, such as those designed for the Argyle Street Tea Rooms or the Hill House, are perhaps his most recognizable furniture pieces. These were not merely functional objects but sculptural elements that defined and articulated space. Other notable furniture designs include his ladder-back chairs, writing desks, cabinets, and light fittings. Each piece was carefully considered in relation to its specific setting.

The decorative motifs he employed – the stylized rose, the "tree of life," abstract geometric patterns, and elongated female figures (often designed by Margaret) – were consistently applied across different media, creating a unified aesthetic. His interiors often featured a subtle interplay of light and dark, with carefully controlled colour schemes that ranged from stark white rooms to more richly coloured and textured spaces.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Mackintosh's style is a complex synthesis of diverse influences, masterfully integrated into a highly personal and original idiom. Key elements include:

Scottish Vernacular: He drew inspiration from traditional Scottish architecture, such as tower houses and castles, evident in the massing and robust forms of his buildings.

Arts and Crafts Movement: He shared the Arts and Crafts emphasis on craftsmanship, honesty of materials, and the integration of art into everyday life. Figures like William Morris and C.F.A. Voysey were important precursors, though Mackintosh's style was generally more austere and less overtly historicist than many Arts and Crafts practitioners.

Japanese Art (Japonisme): Like many artists of his generation, including James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Edgar Degas, Mackintosh was fascinated by Japanese art. The influence of Ukiyo-e prints by artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige can be seen in his use of asymmetry, flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and the sophisticated interplay of pattern and void.

Art Nouveau: While often categorized as an Art Nouveau architect, Mackintosh's version was distinct from the more flamboyant curvilinear styles found in Brussels (Victor Horta) or Paris (Hector Guimard). His lines were often more geometric and controlled, though the organic inspiration and decorative impulse connect him to the broader movement.

Symbolism: The work of "The Four" was deeply imbued with Symbolist tendencies, exploring themes of spirituality, nature, and the inner world. This is particularly evident in their graphic work and Margaret Macdonald's gesso panels. Artists like Jan Toorop and Aubrey Beardsley were exploring similar visual territory.

Emerging Modernism: Mackintosh's emphasis on functionalism, geometric abstraction, and the rejection of excessive historical ornament prefigured many aspects of Modernism. His work can be seen as a bridge between the decorative richness of the late 19th century and the cleaner lines of the 20th.

International Recognition and The Vienna Secession

While Mackintosh's work sometimes met with a mixed or even hostile reception in Britain, it was highly acclaimed on the continent, particularly in Austria and Germany. In 1900, "The Four" were invited to exhibit at the Eighth Vienna Secession exhibition, an influential showcase for avant-garde art and design. Their room was a sensation and had a profound impact on Viennese artists and designers, including Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, and Koloman Moser, who were key figures in the Wiener Werkstätte.

Hoffmann, in particular, acknowledged Mackintosh's influence, and there are clear parallels between Mackintosh's geometric style and the later work of the Wiener Werkstätte. Mackintosh also exhibited in Turin (1902) and Moscow (1902), further cementing his international reputation. German art journals, such as Dekorative Kunst, frequently featured his work, introducing it to a wider European audience. His designs were seen as a refreshing alternative to the more florid Art Nouveau styles prevalent elsewhere.

Later Years, Watercolours, and Personal Anecdotes

Despite his international acclaim, Mackintosh's architectural career began to wane after 1910. Commissions became scarce, partly due to changing tastes and the economic uncertainties leading up to World War I. His uncompromising artistic vision and sometimes difficult personality may also have played a role. In 1914, he and Margaret left Glasgow for Walberswick in Suffolk, England. Here, Mackintosh focused increasingly on watercolour painting, producing a series of exquisite botanical studies and, later, landscapes.

One peculiar anecdote from his life is the change in his surname's spelling. Around 1893, he began signing his name "Mackintosh" instead of "McIntosh." The exact reasons remain unclear, though it has been suggested it was to align with his mother's maiden name, Rennie, or perhaps to distinguish himself or adopt a more "Scottish" sounding name.

During World War I, his foreign-sounding name and habit of sketching the coastline led to him being briefly suspected of being a German spy in Suffolk, a rather absurd accusation for such a patriotic Scot. In 1915, they moved to Chelsea, London, where Mackintosh attempted to re-establish his architectural practice but with little success. He did undertake some textile designs for manufacturers like Foxton's and Selfton's during this period, which show a move towards brighter colours and more abstract, almost Art Deco, patterns.

In 1923, due to ill health and a desire for a more affordable lifestyle, the Mackintoshes moved to the south of France, settling in Port Vendres in the Roussillon region. Here, Mackintosh dedicated himself entirely to watercolour painting, producing a remarkable series of landscapes. These late watercolours are characterized by a strong sense of structure, bold compositions, and a vibrant palette, capturing the unique light and geology of the Mediterranean landscape. They represent a significant body of work in their own right, distinct from his earlier, more Symbolist watercolours.

His health, however, continued to decline. In 1927, he was diagnosed with tongue cancer. He returned to London for treatment but passed away on December 10, 1928, at the age of 60. Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, his devoted wife and collaborator, outlived him by five years, dedicating herself to preserving his legacy.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

During his lifetime, particularly in his later years, Mackintosh's work fell out of fashion in Britain. However, a gradual reassessment began in the 1930s, spearheaded by architectural historians like Nikolaus Pevsner, who recognized his importance as a pioneer of modern design. Pevsner's writings helped to place Mackintosh within the broader context of European Modernism, highlighting his influence on figures like Josef Hoffmann and the Bauhaus movement, even if the latter's connections were more through shared principles than direct lineage with figures like Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe.

The true revival of interest in Mackintosh's work gained momentum in the post-World War II era, accelerating from the 1960s onwards. Exhibitions, publications, and the efforts of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society (founded in 1973) have brought his achievements to a global audience. Today, his buildings are cherished landmarks, and his furniture designs are highly sought after, with original pieces commanding high prices and reproductions widely available.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent generations of architects and designers who have admired his holistic approach, his innovative use of space and light, and his ability to create designs that are both functional and profoundly poetic. He demonstrated that modern design did not have to be cold or impersonal but could be imbued with warmth, symbolism, and a deep connection to place and culture.

Influence on Contemporaries and Successors

Mackintosh's impact was most immediately felt among his contemporaries in Vienna. The stark geometry and refined elegance of his work provided a new direction for artists like Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, who were seeking to move beyond the more ornamental aspects of Jugendstil. The clean lines and functional clarity of his designs resonated with the emerging modernist ethos across Europe.

While his direct influence on British architecture was perhaps less pronounced during his lifetime, his principles of integrated design and his reinterpretation of vernacular traditions found echoes in the work of later architects. His emphasis on craftsmanship and the artistic quality of everyday objects also aligned with the ongoing ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, even as his aesthetic diverged.

In a broader sense, Mackintosh's legacy lies in his demonstration of how an architect could be a "universal designer," shaping every aspect of the built environment. This holistic vision, also pursued by contemporaries like Frank Lloyd Wright in America, was a crucial precursor to the interdisciplinary approach of later design movements. His ability to synthesize diverse influences – Scottish tradition, Japanese art, natural forms – into a coherent and original style remains a powerful example for designers today. His work reminds us that innovation can be deeply rooted in tradition and that beauty and utility can coexist harmoniously.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was a visionary artist whose contributions transcended the boundaries of architecture, design, and painting. His unique style, born from a rich tapestry of influences and a deeply personal artistic sensibility, left an indelible mark on the early 20th century. From the iconic structure of the Glasgow School of Art to the intimate elegance of The Hill House and the vibrant patterns of his late watercolours, Mackintosh's work is characterized by its integrity, innovation, and profound beauty. Though his career was marked by periods of intense creativity and frustrating neglect, his posthumous recognition has firmly established him as one of the most important and original figures in the history of modern design, a Scottish master whose influence continues to resonate globally. His legacy is not just in the buildings and objects he created, but in the enduring power of his holistic and deeply human approach to design.