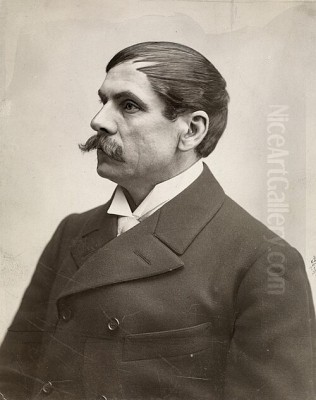

Christian Eriksen Skredsvig stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Norwegian art history. A painter and writer whose life spanned from March 12, 1854, to January 19, 1924, Skredsvig navigated the transition from Realism to Neo-Romanticism, leaving an indelible mark through his evocative landscapes and sensitive portrayals of Norwegian life. His journey took him from the rural settings of Norway to the bustling art centers of Europe and back again, shaping a unique artistic vision that captured the spirit of his homeland while engaging with broader international currents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in the municipality of Modum in Buskerud, Norway, Skredsvig showed artistic promise from a young age. His formal training began at fifteen when he enrolled in Johan Fredrik Eckersberg's painting school in Kristiania (now Oslo). Eckersberg, a notable landscape painter himself, provided a foundation grounded in the observation of nature, steering away from the more formulaic approaches prevalent earlier. This initial schooling was crucial in setting Skredsvig on a path dedicated to artistic pursuit.

Seeking further development, Skredsvig moved to Copenhagen. There, he studied under the guidance of the respected landscape painter Vilhelm Kyhn between 1870 and 1874. Kyhn, known for his atmospheric depictions of the Danish countryside, recognized Skredsvig's talent and played a pivotal role in securing him a free place at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. This period in Copenhagen exposed Skredsvig to the Danish Golden Age traditions and further honed his skills in landscape representation, emphasizing careful study and a connection to the natural world.

Parisian Influence and International Recognition

Like many ambitious Scandinavian artists of his generation, Skredsvig was drawn to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the latter half of the 19th century. He arrived in the French capital seeking exposure to new ideas and techniques. In Paris, he continued his studies under prominent academic painters, including Léon Bonnat, known for his portraiture and historical paintings, and the German animal painter Heinrich von Zügel, who was based in Munich but influential. This diverse training broadened Skredsvig's technical repertoire.

His time in Paris was not confined to the studio. Skredsvig absorbed the influences swirling around him, particularly the impact of French Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, who focused on depicting everyday life and the rural peasantry without idealization. While Skredsvig's work retained a distinct lyrical quality, the emphasis on truthful observation found in Realism resonated with his own inclinations.

Skredsvig's talent quickly gained recognition. He began exhibiting his work, making his debut at an industrial exhibition in 1873. A major breakthrough occurred in 1881 when his painting Une ferme à Venoix (A Farm at Venoix) was awarded a gold medal (first prize) at the prestigious Paris Salon. This large-scale work, depicting a realistic scene of a French farm courtyard bathed in clear light, demonstrated his mastery of naturalist detail and composition. The award brought him significant acclaim and established his reputation on the international stage. During these years, he also traveled extensively, visiting Italy, Spain, and Corsica, further enriching his visual experiences.

Return to Norway: The Fleskum Summer

Despite his success abroad, Skredsvig felt a strong pull back to his native Norway. He returned in 1885, eventually settling at the Fleskum farm near Lake Dælivannet in Bærum, close to Kristiania. The summer of 1886 at Fleskum became legendary in Norwegian art history. Skredsvig, along with a group of fellow artists who had also studied abroad, gathered there, forming an informal artists' colony. This group, often referred to as the "Fleskum Painters," included prominent figures like Erik Werenskiold, Eilif Peterssen, Gerhard Munthe, Harriet Backer, and Kitty Kielland.

The "Fleskum Summer" marked a significant moment in the development of Norwegian Neo-Romanticism and stemningsmaleri (mood painting). These artists sought to move beyond the objective documentation of Naturalism to capture the specific, evocative atmosphere of the Norwegian landscape, particularly the ethereal light of the Nordic summer evenings. They aimed to create art that was distinctly Norwegian, imbued with lyrical feeling and a deep connection to nature and national identity. Skredsvig was a central figure in this movement, contributing significantly to its aesthetic direction.

Artistic Style: From Naturalism to Neo-Romanticism

Skredsvig's artistic style evolved throughout his career, reflecting both his training and his personal artistic temperament. His early works, influenced by his studies in Copenhagen and Paris, are characterized by a detailed Naturalism. Une ferme à Venoix is a prime example of this phase, showcasing meticulous rendering and a clear, objective light. He demonstrated a strong ability to capture textures, forms, and the specificities of a scene with accuracy.

Following his return to Norway and the Fleskum period, his style shifted. While retaining a foundation in careful observation, his work became increasingly infused with subjective feeling and atmosphere. He became a master of depicting the subtle nuances of light, particularly the blue tones of twilight and the soft glow of summer nights. This transition marks his move towards Neo-Romanticism, a style that emphasized emotion, symbolism, and a mystical connection to nature, often drawing inspiration from folklore and national heritage.

Skredsvig is considered a pioneer of plein air (open-air) painting in Norway, taking his easel outdoors to capture the immediate effects of light and atmosphere directly from nature. However, unlike many French Impressionists who focused on fleeting moments and broken brushwork, Skredsvig's plein air studies often served as a basis for more composed studio paintings where mood and lyrical quality were paramount. His "mood paintings" sought to convey a specific emotional response to the landscape, often tinged with melancholy or poetic sensibility.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as defining examples of Christian Skredsvig's artistry and his contribution to Norwegian art:

Une ferme à Venoix (A Farm at Venoix, 1881): This Salon-winning painting cemented his early reputation. Its detailed naturalism, depicting everyday life on a French farm, showcases his technical skill and observational powers honed during his time abroad. It represents the culmination of his engagement with French Realism and Naturalism.

Seljefløyten (The Willow Flute, 1889): Perhaps his most iconic work, Seljefløyten epitomizes the Fleskum mood painting style. It depicts a young boy sitting by the water's edge in the blue twilight, playing a traditional willow flute. The painting is imbued with a quiet, lyrical melancholy and a deep sense of connection between the figure and the Nordic landscape. It captures the essence of the Norwegian summer night atmosphere that the Fleskum artists sought to express.

Menneskens Søn (The Son of Man, 1891): This painting marks a significant development, incorporating religious themes into a contemporary Norwegian setting. It depicts Jesus walking in a recognizable landscape from Skredsvig's home region of Modum. By placing a biblical figure in an everyday Norwegian environment, Skredsvig challenged traditional religious iconography and infused the scene with a personal, national resonance. It reflects the Neo-Romantic interest in symbolism and spiritual dimensions within the familiar world.

Oktobermorgen ved Grez (October Morning near Grez): Reflecting his time spent in the artists' colony at Grez-sur-Loing in France (popular with Scandinavian artists like Carl Larsson and Karl Nordström), this work likely captures the specific light and atmosphere of the French countryside, albeit through his developing personal lens.

Vinteraften ved Sjøen (Winter Evening by the Sea): Skredsvig also captured the stark beauty of the Norwegian winter landscape, exploring different moods and light conditions associated with the colder seasons.

Munken Vendte (The Monk Returned, 1905): This later work, noted for being in its "Skredsvig original frame," suggests his continued exploration of narrative or symbolic themes, possibly drawing on historical or literary sources, within his characteristic landscape style.

These works illustrate the breadth of Skredsvig's subjects and the evolution of his style, from detailed Naturalism to evocative Neo-Romantic mood painting, often blending landscape with figure and narrative elements.

Connections and Friendships: Edvard Munch

Christian Skredsvig moved within a vibrant circle of artists, both in Norway and abroad. His friendship with Edvard Munch (1863-1944), one of the pioneers of Expressionism, is particularly noteworthy. Their paths crossed significantly during a period spent in Nice, France, around 1891-1892. Munch, younger and struggling with intense emotional turmoil and artistic direction, stayed with Skredsvig and his first wife, Maggie Plathe, in a rented villa.

Accounts from this time suggest Skredsvig played a supportive role for Munch. One anecdote relates Skredsvig encouraging Munch to paint a particularly intense, blood-red sunset, even when Munch felt frustrated by the limitations of paint to capture the raw emotion of the scene. Skredsvig, already an established artist, offered encouragement and perhaps a sounding board for Munch's burgeoning ideas about expressing inner psychological states – what Munch would later term "soul painting."

While their artistic paths ultimately diverged significantly – Skredsvig embracing a lyrical Neo-Romanticism and Munch forging the path of Expressionism – their interaction highlights the collegial and sometimes influential relationships within the Norwegian art scene. Skredsvig's relative stability and established position may have provided a valuable, albeit temporary, anchor for the more volatile Munch during a critical phase of his development. Their friendship underscores the interconnectedness of artists striving to define modern art in Norway.

Later Life in Eggedal: Hagan

In 1894, after separating from his first wife, Skredsvig sought refuge and a new beginning. He moved to the remote valley of Eggedal in Sigdal municipality, Buskerud. There, in 1896, he married Beret Berg, a young woman from the area, with whom he had four children. He found deep inspiration in the landscapes and rural life of Eggedal and decided to build a permanent home there.

He designed and constructed his house, Hagan, which was completed around 1899. Hagan became his sanctuary, studio, and family home for the rest of his life. Situated with magnificent views of the valley and Lake Soneren, it provided the perfect environment for his art and writing. Today, Hagan is preserved as a museum dedicated to Skredsvig's life and work, offering visitors a unique insight into his world.

During his years in Eggedal, Skredsvig continued to paint, often depicting the local scenery and people. He also dedicated significant time to writing, publishing several autobiographical books, novels, and short stories, including Dage og Nætter (Days and Nights) and Romaner og Fortællinger (Novels and Stories). His writing often mirrored the themes found in his paintings – a deep love for nature, reflections on life in rural Norway, and a lyrical, sometimes nostalgic tone.

Skredsvig in Context: Norwegian and European Art

Christian Skredsvig occupies a crucial position in the narrative of late 19th and early 20th-century Norwegian art. He belonged to a generation that sought to establish a distinctly national form of expression, moving away from the dominance of foreign academies, particularly the Düsseldorf School represented by earlier figures like Hans Gude and Adolph Tidemand.

His engagement with French Naturalism, alongside contemporaries like Erik Werenskiold and Fritz Thaulow, brought a new level of realism and plein air practice to Norway. His subsequent embrace of Neo-Romanticism and mood painting during the Fleskum period placed him at the forefront of a movement that defined Norwegian art in the 1890s, alongside Gerhard Munthe, Harriet Backer, and Eilif Peterssen. This movement paralleled similar developments in other Nordic countries, seen in the work of artists like Akseli Gallen-Kallela in Finland and Prince Eugen in Sweden, who also sought to capture the unique spirit and atmosphere of their national landscapes.

Compared to the French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Skredsvig's focus was less on the optical effects of light and more on its emotive power. His Naturalism had affinities with painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage, who combined detailed realism with a degree of sentiment. His later work, with its emphasis on mood and symbolism, connects to the broader European Symbolist movement, though always filtered through a distinctly Norwegian sensibility.

While perhaps overshadowed internationally by his friend Edvard Munch, Skredsvig's contribution was vital within Norway. He helped modernize Norwegian painting, championed landscape as a primary subject imbued with national feeling, and fostered a sense of community among artists. His ability to synthesize international trends with local character made him a key transitional figure, bridging the gap between 19th-century Realism and the more subjective approaches of the early 20th century. His influence can be seen in later Norwegian landscape painters, such as Harald Sohlberg, known for his own evocative depictions of Norwegian nature.

Legacy

Christian Skredsvig passed away at his beloved home, Hagan, in 1924. He left behind a rich legacy as both a painter and a writer. His artworks are held in major Norwegian collections, including the National Museum in Oslo, and his home in Eggedal remains a testament to his life and artistic vision.

His importance lies in his mastery of landscape painting, his pioneering role in Norwegian mood painting and Neo-Romanticism, and his ability to capture the subtle beauty and specific atmosphere of the Norwegian natural world. He successfully navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, absorbing international influences while forging a style that was deeply personal and rooted in his homeland. Through works like Seljefløyten and Menneskens Søn, he created enduring images that continue to resonate with audiences, offering a poetic and deeply felt vision of Norway. Christian Skredsvig remains a cherished and essential figure in the story of Norwegian art.