Cornelis de Wael stands as a significant figure in the vibrant tapestry of 17th-century European art. Born in the bustling artistic hub of Antwerp in 1592, he navigated the complex cultural currents of his time, ultimately becoming a pivotal link between the Flemish and Italian art worlds. His life and career, primarily centered in Genoa, Italy, reflect a fascinating blend of artistic creation, entrepreneurial spirit, and cultural exchange. De Wael was not only a prolific painter known for his diverse subject matter but also an influential teacher, collaborator, and art dealer, leaving an indelible mark on the Baroque era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Cornelis de Wael was born into an environment steeped in artistic tradition. His father, Jan de Wael I (1558-1633), was a respected painter in Antwerp, ensuring that Cornelis and his elder brother, Lucas de Wael (1591-1661), who also became a painter, were exposed to the craft from a young age. Their mother, Gertrude de Jode, hailed from the de Jode family, renowned engravers and print publishers, further embedding the brothers within Antwerp's artistic milieu. This familial background provided a solid foundation for Cornelis's artistic education, likely beginning under his father's tutelage.

Antwerp, during Cornelis's youth, was a major European center for art production and trade, still resonating with the influence of masters like Peter Paul Rubens. Growing up in this dynamic atmosphere, de Wael would have absorbed the prevailing trends of Flemish Baroque art, characterized by rich colors, dynamic compositions, and a penchant for realism, even within historical or allegorical subjects. While specific details of his early training beyond his father's workshop are scarce, his later work demonstrates a thorough grounding in Flemish techniques and aesthetics.

The Move to Italy and the Genoese Period

In 1619, seeking broader horizons and opportunities, Cornelis de Wael, accompanied by his brother Lucas, embarked on a journey to Italy, a common destination for ambitious Northern European artists. They initially traveled, perhaps passing through Rome, but ultimately settled in Genoa. This prosperous port city, the capital of the Republic of Genoa, offered a welcoming environment with wealthy patrons eager for art, particularly works by Flemish artists whose reputation for skill and detail was highly regarded.

The de Wael brothers established a successful workshop in Genoa, which quickly became a central point for the Netherlandish artistic community in the city. Cornelis would spend the vast majority of his adult life and career in Genoa, nearly four decades, deeply integrating himself into its social and artistic fabric. His long residency allowed him to build extensive networks among the local aristocracy, fellow artists, and collectors, solidifying his position not just as a painter but as a key figure in the city's cultural life.

The Genoese period was marked by immense productivity and influence. The de Wael studio served as a home away from home, a place of work, and a trading post for visiting artists from the Low Countries. This created a vibrant micro-community, fostering collaboration and facilitating the adaptation of Flemish styles to Italian tastes, and vice versa. Cornelis's presence provided stability and support for many compatriots navigating the Italian art scene.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Cornelis de Wael's art is characterized by its versatility and keen observation. While rooted in Flemish traditions, his style evolved through his long exposure to the Italian environment. He maintained a Northern European attention to detail, meticulous rendering of textures, and lively depiction of figures, but often incorporated the dramatic lighting and dynamic compositions associated with the Italian Baroque. His palette could range from earthy tones in rustic scenes to vibrant hues in more elaborate compositions.

His thematic range was notably broad. De Wael excelled in depicting battle scenes, both on land and at sea. These works are often filled with numerous small figures engaged in chaotic action, rendered with remarkable clarity and energy. He captured the drama and brutality of conflict, a popular genre during the turbulent 17th century. These scenes often showcased his skill in organizing complex compositions and differentiating myriad figures and actions within a single frame.

Beyond warfare, de Wael frequently painted genre scenes, capturing aspects of everyday life. These could range from bustling port scenes and peasant gatherings to more refined depictions of elegant companies enjoying leisure activities. He also produced religious paintings, notably a series depicting the Seven Works of Mercy, where biblical or moral themes were illustrated through contemporary settings and figures, making them relatable and impactful for his audience. Landscape painting, often featuring coastal views or idealized pastoral settings, also formed part of his oeuvre, sometimes created in collaboration with his brother Lucas.

Masterpieces and Representative Works

Several works stand out in Cornelis de Wael's extensive output, showcasing his skill across different genres. His series illustrating the Seven Works of Mercy (e.g., Visiting the Prisoners, Feeding the Hungry) are significant examples of his religious and genre painting. These works combine moral instruction with vivid depictions of contemporary Genoese life, populated by realistically portrayed figures from various social strata. The detailed settings and expressive interactions between characters are hallmarks of his style.

Battle scenes, such as his numerous depictions of cavalry skirmishes or naval engagements like Naval Battle between Christians and Turks, were highly sought after. These paintings demonstrate his ability to manage complex, multi-figure compositions, capturing the dynamism and chaos of combat with meticulous detail in armor, weaponry, and the struggling forms of men and horses. The accuracy in depicting ships and naval action also points to his careful observation, fitting for an artist based in a major maritime republic.

Works like An Elegant Company Making Music represent another facet of his art, depicting the refined pastimes of the upper classes. These paintings often feature richly dressed figures in sophisticated interiors or garden settings, engaged in conversation, music, or games. They highlight de Wael's skill in rendering luxurious fabrics, intricate details of decor, and the subtle social interactions of his subjects, offering a glimpse into the lifestyle of his patrons. His ability to capture atmosphere, whether the gritty reality of a battlefield or the polished ambiance of an aristocratic gathering, was a key strength.

Collaborations and Workshop Practices

Collaboration was a common practice in the 17th century, particularly in large artistic centers like Antwerp and Genoa, and Cornelis de Wael actively engaged in it. His most consistent collaborator was undoubtedly his brother, Lucas de Wael, with whom he shared a studio for many years. While distinguishing their individual hands can sometimes be challenging, Lucas is often credited with specializing more in landscapes, which may have formed the settings for figures painted by Cornelis.

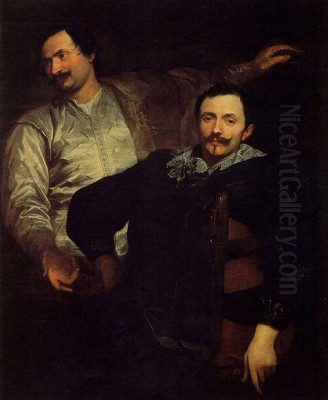

Perhaps the most famous artist associated with the de Wael brothers in Genoa was Anthony van Dyck. During Van Dyck's extended stay in Genoa (1621-1627), he developed a close relationship with Cornelis and Lucas. Van Dyck even resided with them for a period. This association likely led to artistic exchange, and Van Dyck famously painted a striking double portrait of the brothers, immortalizing their partnership and presence in the city. While direct collaboration on single canvases might be difficult to prove definitively, their interaction within Genoa's close-knit art world was significant.

Cornelis also collaborated with other specialists. It is recorded that he worked with the renowned Flemish animal and still life painter Frans Snyders, and possibly Snyders' brother Paul. These artists might have added elements like fruit, game, or animals to de Wael's compositions, a practice that leveraged the specific skills of different masters to create richer, more complex works. Similarly, collaborations with landscape specialists like Jan Wildens, another Flemish painter who spent time in Italy, are documented, with Wildens providing background settings for de Wael's figures.

Furthermore, the de Wael workshop in Genoa functioned as a training ground. Cornelis took on pupils, the most notable being his nephew, Jan Baptist de Wael (son of Lucas), ensuring the continuation of the family's artistic legacy. The workshop was a hub of activity, producing original works, copies, and potentially employing assistants to meet demand, reflecting the operational structure of successful Baroque studios.

The Role of Art Dealer and Cultural Mediator

Cornelis de Wael's significance extends beyond his own artistic production. He played a crucial role as an art dealer and cultural mediator in Genoa. Leveraging his extensive network and his position within both the Flemish expatriate community and Genoese society, he facilitated the trade of artworks between the Low Countries and Italy. This involved importing paintings by Flemish masters and exporting Italian works northwards, contributing to the cross-pollination of styles and tastes.

His home and workshop became a vital contact point for Flemish artists arriving in Genoa. He provided lodging, support, introductions to patrons, and potentially commissions or employment within his own studio projects. This function was invaluable for artists navigating a foreign environment, helping them establish themselves in the competitive Italian art market. Figures like Van Dyck benefited from this network upon their arrival. De Wael essentially acted as a cultural anchor and facilitator for the Flemish artistic diaspora in Liguria.

This entrepreneurial aspect of his career was not unusual for artists of the period, but de Wael seems to have pursued it with particular success. His activities helped to shape Genoese collections, introducing works by prominent Flemish artists and potentially influencing local tastes. His dual role as creator and dealer placed him at the heart of the artistic economy of his adopted city, making him a central figure in the cultural exchange between Northern and Southern Europe during the Baroque era.

Printmaking Activities

In addition to his prolific output as a painter, Cornelis de Wael was also active as a printmaker, primarily working in etching. This medium allowed for wider dissemination of his compositions and themes. His prints often mirrored the subjects found in his paintings, including military scenes, genre depictions, and landscapes. Etching, with its capacity for fluid lines and tonal variation, suited his detailed and lively style.

His prints, like his paintings, often featured numerous small figures and intricate details. One notable example sometimes cited is a print titled Marine at the Gates of Byzantium, showcasing his interest in maritime subjects and exotic locales, blending topographical interest with imaginative composition. His series of etchings depicting the Works of Mercy also helped to popularize these compositions beyond the original painted versions.

The production of prints served multiple purposes. It allowed de Wael to reach a broader audience than paintings alone could, potentially increasing his fame and influence. Prints were more affordable than paintings, making his imagery accessible to a wider market. They could also serve as models for other artists or as records of his inventions. His activity in this medium underscores his versatility and his engagement with the various means of artistic production and distribution available in the 17th century.

Later Years and Legacy

After nearly four decades of continuous activity in Genoa, Cornelis de Wael's life took a final turn. Around 1656, he moved from Genoa to Rome, the ultimate center of the Italian art world. He was joined there by his nephew and pupil, Jan Baptist de Wael. The reasons for this late move are not entirely clear, but Rome offered prestigious patronage networks and was a magnet for artists throughout Europe. He spent the last years of his life in the Eternal City, continuing to work until his death in 1667.

Cornelis de Wael's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he left behind a substantial body of work characterized by its thematic diversity, lively execution, and blend of Flemish detail with Italianate dynamism. His depictions of battles and genre scenes were particularly influential and popular. His long presence in Genoa made him a cornerstone of the city's artistic life for much of the 17th century.

His role as a cultural mediator and supporter of fellow Flemish artists in Italy was equally significant. The de Wael workshop was more than just a place of production; it was a vital node in the network connecting Northern European artists with the Italian art scene. Through his activities as a dealer and host, he facilitated countless careers and contributed significantly to the rich artistic exchange that characterized the Baroque period. He helped to solidify the reputation of Flemish painting in Italy while also absorbing and transmitting Italian influences back through his connections.

Influence on Contemporaries and Later Artists

Cornelis de Wael's impact resonated both during his lifetime and afterwards. Within Genoa, his style and thematic choices influenced local painters. His genre scenes, particularly those depicting low-life subjects or the Works of Mercy, found echoes in the work of Genoese artists who explored similar themes. His dynamic battle paintings also contributed to the popularity of this genre in the region.

One of the most frequently cited artists influenced by de Wael is the later Genoese painter Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749), known for his highly individualistic, flickering brushwork and often dark, dramatic scenes. While Magnasco developed a unique style, some scholars suggest that de Wael's depictions of common life, soldiers, and scenes with a certain atmospheric, sometimes unsettling quality, may have provided an early point of reference, particularly in terms of subject matter and a focus on expressive figuration.

His influence extended to Flemish artists who passed through Genoa or were part of his circle, such as Pieter van Lint. The presence of his works in collections, facilitated by his dealing activities, also meant his compositions were known beyond his immediate circle. While perhaps not as stylistically groundbreaking as contemporaries like Rubens or Rembrandt, de Wael's consistent quality, thematic breadth, and central position in Genoese art life ensured his work was seen and appreciated.

Some art historians have also tentatively suggested connections or shared interests with slightly earlier Dutch painters like Joachim Wtewael or Abraham Bloemaert, particularly in the handling of multi-figure historical or genre scenes, though direct influence pathways are complex and debated. What is clear is that de Wael operated within a broad European network where artistic ideas circulated widely. Other Genoese contemporaries like Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione or Valerio Castello, while pursuing distinct artistic paths, would certainly have been aware of de Wael's prominent position and prolific output.

Historical Assessment and Reputation

Historically, Cornelis de Wael's reputation has perhaps been somewhat overshadowed by the towering figures of Flemish Baroque painting like Rubens and Van Dyck. Some assessments, particularly in earlier art historical writing, might have viewed his style as competent but less innovative compared to these giants. His focus on genre and battle scenes, while popular, sometimes led to him being categorized primarily as a specialist painter rather than a master of the grand manner.

However, modern scholarship increasingly recognizes the importance of figures like de Wael, who operated at the crucial intersections of different artistic cultures and markets. His role in Genoa, both as an artist and as a facilitator, is now better understood and appreciated. His paintings are valued for their skillful execution, their lively portrayal of 17th-century life and conflict, and their unique synthesis of Flemish and Italian elements.

His works are held today in numerous major museums across Europe and the world, including the Louvre in Paris, the Prado in Madrid, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, and the British Museum in London (particularly prints). The continued presence of his art in these prestigious collections attests to his enduring significance. Cornelis de Wael emerges not just as a talented painter, but as a key figure who actively shaped the artistic landscape of Baroque Italy, leaving a rich legacy through his art, his influence, and his role in fostering international artistic exchange.