Cornelis Schut I (1597-1655) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the vibrant tapestry of 17th-century Flemish Baroque art. Born in Antwerp, the bustling artistic hub of Northern Europe, Schut carved out a distinguished career as a painter, etcher, and designer of tapestries. His oeuvre, rich with religious and mythological scenes, reflects both the profound influence of his contemporaries, most notably Peter Paul Rubens, and a distinct artistic personality that evolved through his experiences in Flanders and Italy. While often working in the shadow of giants like Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Jacob Jordaens, Schut's contributions to the visual culture of his time were substantial, leaving behind a legacy of dynamic compositions, expressive figures, and a mastery across various artistic media.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Cornelis Schut was baptized in Antwerp on May 13, 1597. The city was then a crucible of artistic innovation, still basking in the afterglow of its Golden Age and fiercely reasserting its Catholic identity in the wake of the Counter-Reformation. This religious fervor provided ample commissions for artists, particularly for large-scale altarpieces and decorative schemes for churches and monastic orders. It was in this environment that Schut began his artistic training.

While no definitive apprenticeship records link him directly as a registered pupil in Peter Paul Rubens's workshop, the stylistic affinities between Schut's work and that of the older master are undeniable. Rubens's studio was the most dominant artistic force in Antwerp, and its influence permeated the city's artistic production. Schut’s robust figures, dynamic compositions, and rich, warm palette often echo Rubens's powerful style. It is highly probable that Schut spent time in Rubens's circle, absorbing his techniques and artistic vision, even if not formally enrolled. Some scholars suggest he may have been one of Rubens's most talented pupils, adept at emulating the master's energetic brushwork and dramatic flair.

Beyond Rubens, the artistic milieu of Antwerp would have exposed Schut to other influential figures. The legacy of earlier masters like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and the contemporary work of artists such as Jan Brueghel the Elder, known for his detailed landscapes and flower paintings, and the figure painter Hendrick van Balen, would have contributed to the rich visual vocabulary available to a young, aspiring artist. In 1618, Schut achieved a significant milestone by becoming a master in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke, the city's venerable institution for painters, sculptors, and other craftsmen. This membership officially recognized his status as an independent artist, capable of taking on his own commissions and pupils.

The Italian Sojourn: Rome and the Bentvueghels

Like many Northern European artists of his generation, Cornelis Schut was drawn to Italy, the wellspring of classical antiquity and Renaissance art, and the contemporary powerhouse of the Baroque. Between 1624 and 1627, he resided in Rome, a city teeming with artistic ferment. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to the works of Italian masters and fostering a more nuanced understanding of Baroque aesthetics.

In Rome, Schut became a founding member of the "Bentvueghels" (Dutch for "birds of a feather"), a society of predominantly Dutch and Flemish artists working in the city. This confraternity was known for its bohemian lifestyle, its members adopting whimsical nicknames (Schut's was reportedly "Broodzak," meaning bread bag) and engaging in Bacchic initiation rituals. Beyond the revelry, the Bentvueghels provided a support network for expatriate artists, facilitating the exchange of ideas and professional opportunities. Notable contemporaries in Rome whose work Schut would have encountered included the revolutionary Caravaggio (though deceased by then, his influence was pervasive), the classicizing Annibale Carracci, and the burgeoning genius of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

During his Italian stay, Schut absorbed the influences of contemporary Italian Baroque painters. He was particularly receptive to the classicism of artists like Guido Reni and Domenichino, and the more dynamic, High Baroque style of Pietro da Cortona. These influences tempered the overt Rubenesque qualities of his earlier work, leading to compositions that often balanced Flemish exuberance with Italianate grace and a more controlled sense of drama. One significant commission from this period was the design of tapestries for the Arazzeria Medici, the tapestry workshop of Cosimo II de' Medici in Florence, indicating his growing reputation.

However, his time in Italy was not without turmoil. In 1627, Schut was implicated in the death of a fellow artist named Giusto. He was arrested but eventually released, reportedly through the intervention of the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's prestigious academy of arts. This incident, though resolved, cast a shadow and may have precipitated his return to Antwerp later that year or in early 1628.

Return to Antwerp and Mature Career

Upon his return to Antwerp, Cornelis Schut re-established himself as a prominent artist. His Italian experiences had enriched his style, adding a layer of sophistication and a broader palette of compositional strategies. He quickly found favor, receiving numerous commissions for altarpieces, private devotional paintings, and large-scale decorative projects. The Counter-Reformation continued to fuel demand for religious art, and Schut's ability to create compelling and emotionally resonant scenes made him a sought-after painter.

He produced significant works for various churches and religious institutions in Antwerp and beyond. Among his most ambitious undertakings was the monumental dome painting of the Assumption of the Virgin for Antwerp Cathedral, a vast canvas soaring 43 meters high, executed between 1645 and 1647. This commission, in such a prominent location, speaks volumes about his standing in the city. He also painted the Martyrdom of Saint George as an altarpiece for the high altar of the Church of St. George in Antwerp, a work that showcases his skill in depicting dramatic, multi-figure compositions.

Schut was also involved in creating ephemeral decorations for important civic events. In 1635, he collaborated with other leading Antwerp artists, under the general direction of Rubens, on the lavish decorations for the Triumphal Entry of Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria into Antwerp. Such projects required rapid execution and a flair for grand, allegorical statements, skills Schut possessed in abundance. His collaborations extended to working with other painters, such as the figure painter Gerard Seghers and the prolific Gaspar de Crayer, who, like Schut, was a prominent creator of altarpieces.

Throughout his mature career, Schut maintained a busy workshop, likely employing assistants to help with large commissions, a common practice at the time. He continued to paint a wide range of subjects, from grand religious narratives to smaller, more intimate mythological scenes and allegories, demonstrating his versatility and adaptability to different scales and patronal demands.

Mastery Across Media: Paintings, Etchings, and Designs

Cornelis Schut's artistic output was not confined to oil painting; he was also a gifted etcher and a capable designer for other media, most notably tapestries. This versatility was characteristic of many successful Baroque artists who often moved fluidly between different forms of artistic expression.

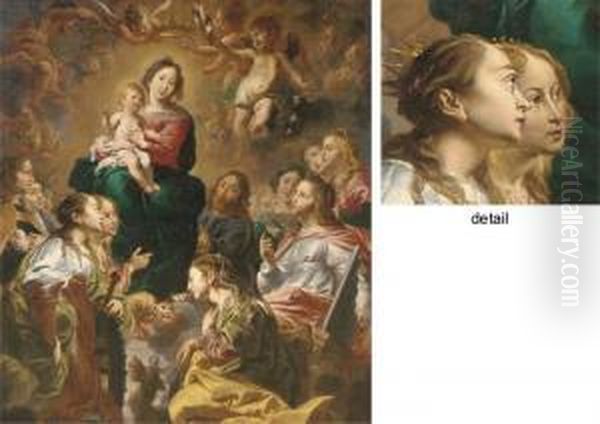

Oil Paintings

The core of Schut's reputation rests on his oil paintings. His religious works were particularly significant, aligning with the spiritual and didactic aims of the Counter-Reformation. Works like the Inmaculada Concepción (Immaculate Conception), now in the Granada Seminary in Spain, exemplify his ability to convey profound theological concepts with visual eloquence. The painting depicts the Virgin Mary, serene and majestic, surrounded by angels, embodying the doctrine of her sinless conception. His Adoration of the Magi (circa 1626) is another example of a popular biblical theme rendered with characteristic Baroque dynamism and rich coloration.

Mythological subjects also featured prominently in his painted oeuvre. These scenes, often drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses or other classical sources, allowed for a display of erudition and an exploration of human emotion and drama, often with a sensuous depiction of the nude or semi-nude figure. His style in these works, as in his religious paintings, blended Flemish energy with Italianate forms, creating compositions that were both lively and harmoniously structured.

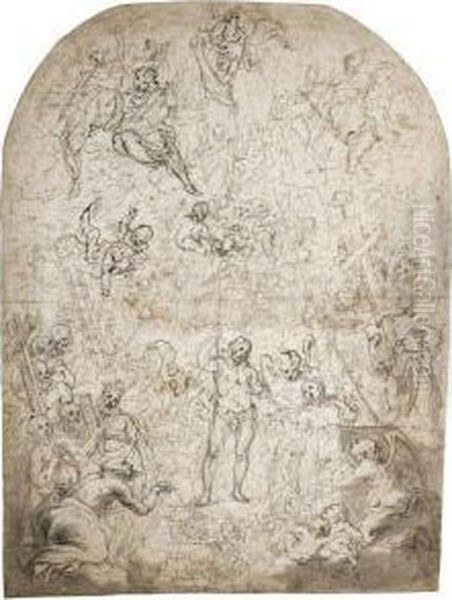

Etchings and Prints

Cornelis Schut was an accomplished etcher, and his prints played a crucial role in disseminating his compositions and style to a wider audience. His etchings are characterized by a free, almost spontaneous line, often described by the term "krabbelstijl" (scribbled style), which lent them a remarkable vivacity and immediacy. This technique, while appearing effortless, required considerable skill to control.

Among his notable etchings are The Madonna and Child, a tender depiction of a classic theme, and Four Naked Children on a Swing (circa 1640), a charming and playful scene that showcases his ability to capture movement and youthful energy. Another powerful etching is Judith and Holofernes, illustrating the dramatic biblical story with intensity. His prints often explored the same religious and mythological themes as his paintings, but the medium of etching allowed for a different kind of expressive freedom. He sometimes collaborated with other printmakers, such as the renowned Bohemian etcher Wenceslaus Hollar, who engraved some of Schut's designs, further extending their reach.

Tapestry Designs

Schut's involvement in tapestry design, evidenced by his work for the Medici in Florence, continued after his return to Antwerp. Tapestries were among the most luxurious and prestigious art forms of the Baroque era, adorning the palaces of royalty and the wealthy elite. Designing for tapestry required a specific set of skills, including the ability to create clear, legible compositions that could be translated into woven form, often on a monumental scale. Schut's experience with large-scale painted decorations served him well in this demanding field. His tapestry designs, like his paintings, would have featured complex figural arrangements and rich narrative content, suitable for the opulent tastes of the time.

Artistic Style and Characteristics

Cornelis Schut's artistic style is a fascinating synthesis of various influences, primarily the robust dynamism of the Flemish tradition, epitomized by Rubens, and the more classical or High Baroque tendencies he absorbed during his time in Italy. This fusion resulted in a personal style that, while clearly indebted to Rubens, possessed its own distinct characteristics.

A hallmark of Schut's work is its compositional energy. His figures are often arranged in dynamic, swirling patterns, creating a sense of movement and excitement. This is particularly evident in his large-scale altarpieces and ceiling paintings, where he masterfully handled complex groups of figures in dramatic interaction. He had a strong sense of theatricality, often choosing moments of peak action or emotional intensity for his depictions.

His use of color was rich and varied, often employing a warm palette reminiscent of Rubens, but sometimes incorporating the clearer, brighter tones favored by some Italian painters. He was skilled in the use of chiaroscuro, employing contrasts of light and shadow to model forms, create depth, and enhance the dramatic impact of his scenes. This sensitivity to light effects was likely sharpened by his exposure to the work of Caravaggio and his followers in Rome.

In terms of figural types, Schut developed certain recognizable characteristics. His figures often have rounded faces, small chins, and somewhat pouting mouths. His depictions of putti (cherubic infants) are particularly distinctive and appear frequently in his religious and mythological works, adding a touch of charm or divine presence. The gestures and poses of his figures are typically expressive, conveying a range of emotions from pious devotion to dramatic anguish or playful abandon.

While capable of grand, heroic statements, Schut could also achieve a degree of tenderness and intimacy, especially in his smaller devotional paintings or scenes involving the Virgin and Child. His etchings, with their free and spirited lines, reveal another facet of his artistic personality, showcasing a more spontaneous and perhaps personal mode of expression.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Cornelis Schut operated within a highly competitive and extraordinarily talented artistic environment in Antwerp. His relationship with Peter Paul Rubens was undoubtedly formative. Whether as a direct pupil or a close follower, Schut absorbed much from Rubens's artistic innovations. However, this association also meant that, like many other talented artists of his generation, he often found himself compared to, and sometimes overshadowed by, the towering figure of Rubens.

Other major Antwerp contemporaries included Anthony van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens. Van Dyck, after an early career in Rubens's studio, achieved international fame as a portraitist, though he also produced significant religious and mythological works. Jordaens, known for his robust, earthy style and large-scale genre scenes and mythological paintings, was another dominant force in Antwerp art. Schut's work can be situated alongside these masters, contributing to the rich diversity of the Antwerp school. While perhaps not achieving the same level of international renown as Rubens or Van Dyck, Schut was a respected and successful artist within this vibrant milieu.

His collaborations with artists like Gerard Seghers and Gaspar de Crayer highlight the interconnectedness of the Antwerp art world. Such collaborations were common, allowing artists to combine their strengths on large projects or to meet the demands of a busy market. His association with the Bentvueghels in Rome also placed him within a network of Northern European artists who were actively engaging with and responding to Italian art, a crucial aspect of Baroque artistic exchange. The influence of Italian artists like Guido Reni, Pietro da Cortona, and even the earlier generation of Carracci and Caravaggio, is discernible in the evolution of his style, demonstrating his ability to assimilate and synthesize diverse artistic currents.

Challenges and Reputation

Despite his considerable talents and prolific output, Cornelis Schut's historical reputation has, at times, been somewhat muted, particularly when measured against the colossal fame of Rubens or the international celebrity of Van Dyck. The sheer dominance of Rubens in Antwerp meant that many artists, Schut included, were often perceived primarily in relation to him, either as pupils, followers, or imitators. This, to some extent, could obscure a full appreciation of their individual contributions and stylistic nuances.

The incident in Rome involving the death of the artist Giusto, though Schut was ultimately exonerated, may have caused some contemporary scandal or at least complicated his early career. Furthermore, historical records indicate that his work was not universally praised. For instance, an art dealer named André de Saintes is recorded as having criticized the quality and value of some of Schut's paintings, a reminder that artistic reputations are often subject to the vagaries of contemporary taste and market forces.

In the broader sweep of art history, figures like Johannes Vermeer, with his intimate genre scenes, or later, Vincent van Gogh, with his revolutionary post-impressionism, have captured the popular imagination in ways that many competent and successful Baroque masters like Schut have not. However, this does not diminish Schut's importance within his own historical and artistic context. He was a key player in the Antwerp Baroque, fulfilling major commissions and contributing significantly to the visual culture of the Counter-Reformation.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Cornelis Schut's immediate legacy can be seen in the numerous altarpieces and decorative paintings that adorned churches and private collections in Flanders and beyond. His prints also played a vital role in disseminating his compositions and style, potentially influencing artists who may not have had direct access to his painted works. While he is not known to have had a large school of prominent pupils who carried on a distinct "Schut style," his work undoubtedly formed part of the broader artistic current that shaped the later stages of Flemish Baroque art.

In more recent times, art historical scholarship has increasingly sought to re-evaluate artists who may have been overshadowed by their more famous contemporaries. Exhibitions and focused research have shed new light on figures like Cornelis Schut, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of their achievements and their specific contributions to the art of their time. Such re-evaluations often reveal artists of considerable skill and originality whose work enriches our understanding of the period.

Today, Cornelis Schut I is recognized as a talented and versatile artist who made significant contributions to Flemish Baroque art. His ability to synthesize Flemish dynamism with Italianate elegance, his mastery across different media, and his prolific output of religious, mythological, and allegorical works secure him an important place in the history of 17th-century European art. His paintings and etchings can be found in major museums and collections around the world, testament to his enduring artistic merit.

Conclusion

Cornelis Schut I was an artist of considerable talent and ambition who navigated the dynamic art world of 17th-century Antwerp and Rome with skill and adaptability. Deeply influenced by the towering genius of Rubens, he nevertheless forged a distinctive artistic identity, characterized by energetic compositions, expressive figures, and a rich visual vocabulary. His contributions to religious art during the Counter-Reformation were substantial, and his mastery extended to mythological scenes, tapestry design, and the art of etching.

While the brilliance of some of his contemporaries may have cast long shadows, a closer examination of Schut's career reveals an artist who was highly respected in his own time, capable of undertaking major commissions and producing works of significant aesthetic quality. As art history continues to explore the complexities of the Baroque era, Cornelis Schut I emerges as a key figure in the Flemish tradition, an artist whose work merits continued attention and appreciation for its vitality, craftsmanship, and its eloquent expression of the cultural and spiritual currents of his age.