Jacob Jordaens stands as one of the towering figures of 17th-century Flemish Baroque painting, a contemporary and artistic peer of the celebrated Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. Born in the bustling port city of Antwerp on May 20, 1593, and dying there on October 18, 1678, Jordaens forged a distinct and enduring artistic identity characterized by vibrant energy, earthy realism, and a profound connection to the life and traditions of his homeland. Unlike many ambitious artists of his time, including Rubens and Van Dyck, Jordaens never undertook the customary journey to Italy to study classical antiquity and the Italian masters firsthand. Instead, he absorbed these influences through prints and the works of artists who had made the trip, developing a style that remained deeply rooted in Flemish sensibilities throughout his long and prolific career.

Jordaens's output was remarkably diverse, encompassing grand religious narratives, dynamic mythological scenes, insightful portraits, historical compositions, and, perhaps most famously, exuberant depictions of peasant life and Flemish proverbs. He was not only a master painter in oils but also a highly sought-after designer of tapestries and a capable printmaker. His work resonated with a wide audience, from wealthy merchants and civic institutions in Antwerp to aristocratic and royal patrons across Europe. Even after the deaths of Rubens and Van Dyck, Jordaens maintained his position as the leading painter in Antwerp, running a large and successful workshop that fulfilled numerous prestigious commissions. His art offers a unique window into the culture, spirit, and visual language of the Southern Netherlands during its Golden Age.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Jacob Jordaens was born into a prosperous family in Antwerp. His father, also named Jacob Jordaens, was a successful linen merchant, and his mother was Barbara van Wolschaten. Belonging to the upper echelons of Antwerp society, the young Jordaens received a good education, evident in his clear handwriting and command of French, which set him apart from many contemporary artists. This background likely provided him with a degree of financial security and social standing from an early age. His upbringing in Antwerp, a major European center for art, trade, and finance, exposed him to a rich cultural environment.

At the age of fourteen, around 1607, Jordaens began his formal artistic training as an apprentice to Adam van Noort. Van Noort was a respected painter and a significant figure in the Antwerp art scene, notable also for having been one of the teachers of Peter Paul Rubens. This connection placed Jordaens within a lineage of influential Flemish masters. Van Noort's own style, while less flamboyant than Rubens's, possessed a certain robustness that may have influenced Jordaens's early development. Jordaens remained in Van Noort's studio for a considerable period, developing his technical skills.

In 1615, Jordaens was enrolled as a master painter in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke, the official body governing artists and artisans in the city. Significantly, he was registered as a "waterschilder," a painter in watercolors or gouache on canvas or paper. This medium was often used for temporary decorations, but more importantly, it was the standard medium for creating tapestry cartoons – the full-scale designs weavers used as guides. This early specialization hints at the importance tapestry design would hold throughout his career. Soon after becoming a master, in 1616, Jordaens married his former master's eldest daughter, Anna Catharina van Noort, further solidifying his ties within the Antwerp artistic community. The couple would go on to purchase a substantial house in the Hoogstraat (High Street) in 1618, which Jordaens later expanded, reflecting his growing success and status.

The Artistic Milieu of Antwerp

To fully appreciate Jordaens's career, it is essential to understand the context of Antwerp in the early 17th century. Despite the political and economic challenges following the Dutch Revolt and the Scheldt River blockade, Antwerp remained a vibrant artistic capital, largely fueled by the patronage of the Catholic Church (as part of the Counter-Reformation), the Habsburg governors, the local aristocracy, and a wealthy merchant class. The city was dominated by the towering figure of Peter Paul Rubens, whose dynamic, Italianate Baroque style set the standard for ambitious history painting.

The Guild of Saint Luke played a crucial role in regulating the art market, maintaining standards of craftsmanship, and fostering a sense of community among artists. Membership was essential for practicing professionally. Jordaens's rapid ascent within the Guild, culminating in his election as its dean (head) in 1621, demonstrates his early recognition and respect among his peers. This position involved administrative responsibilities and further enhanced his professional standing.

While Rubens was the undisputed leader, Antwerp boasted numerous other talented artists. Anthony van Dyck, initially Rubens's most gifted assistant, quickly developed his own elegant style, particularly in portraiture, before pursuing an international career. Other notable figures included Frans Snyders, a specialist in animals and still life who frequently collaborated with Rubens and Jordaens; Jan Brueghel the Elder, famed for his detailed flower paintings and landscapes; Cornelis de Vos, a respected portrait painter; and Abraham Janssens, another significant history painter whose style offered a slightly more classical alternative to Rubens's dynamism. Jordaens navigated this competitive yet collaborative environment, learning from his contemporaries while carving out his unique niche.

Development of a Distinct Style: Influence and Independence

Jordaens's artistic development shows a clear absorption of prevailing trends, particularly the influence of Rubens, yet he consistently maintained a distinct artistic personality. Unlike Rubens and Van Dyck, he did not travel to Italy. His understanding of Italian art, particularly the High Renaissance masters like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, and the revolutionary realism of Caravaggio, came primarily through prints and through the works of Rubens himself, who had spent years in Italy. This indirect absorption perhaps allowed Jordaens to integrate these influences more seamlessly into his native Flemish tradition.

His early works, from the late 1610s and 1620s, already display many of his characteristic traits. They often feature strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), reminiscent of Caravaggio's followers (the Caravaggisti), though Jordaens's light is generally warmer and less starkly dramatic. His figures are typically robust, fleshy, and full of life, rendered with a vigorous brushwork. Compositions tend to be crowded, filled with figures, animals, and objects, creating a sense of bustling energy and abundance. Examples like The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1616-1618) showcase his early mastery of warm colors, dynamic grouping, and a tangible, almost rustic, portrayal of sacred figures.

While clearly indebted to Rubens's compositional energy and rich color palette, Jordaens's figures often feel more grounded and less idealized. There is an earthiness and a directness in his portrayal of human emotion and physicality that distinguishes him. He frequently employed members of his own family and household as models, contributing to the sense of immediacy and realism in his paintings. His humor, often bordering on the boisterous or even coarse, also set him apart from the more courtly elegance of Van Dyck or the heroic grandeur often found in Rubens.

Collaboration and Major Commissions

Jordaens's talent did not go unnoticed by Rubens. During the 1620s and 1630s, Jordaens frequently collaborated with Rubens's workshop, assisting the master on large-scale commissions. This involved translating Rubens's preliminary oil sketches (bozzetti) into larger formats or painting specific sections of monumental works under Rubens's supervision. This experience was invaluable, exposing Jordaens to the management of large projects and further refining his technique in the dominant Baroque style.

A particularly significant collaboration occurred in 1637-1638 for the decoration of Philip IV of Spain's hunting lodge, the Torre de la Parada, near Madrid. Rubens oversaw the project, providing numerous sketches based on Ovid's Metamorphoses, which were then executed as large paintings by various Antwerp artists. Jordaens was entrusted with a substantial number of these canvases, demonstrating Rubens's confidence in his abilities. Other artists involved included Cornelis de Vos and Gaspar de Crayer. This project cemented Jordaens's reputation on an international level.

Following Rubens's death in 1640 and Van Dyck's death in London in 1641, Jacob Jordaens became, arguably, the most important and sought-after painter remaining in Antwerp. He inherited many of the types of commissions previously dominated by Rubens, including large altarpieces for churches throughout the Southern Netherlands and beyond, as well as decorative cycles for civic buildings and private residences. His workshop expanded to meet the demand, employing numerous assistants and pupils to help execute the often vast canvases.

Signature Themes and Masterworks

Jordaens excelled across a range of subjects, but he is perhaps best known for his lively interpretations of mythological scenes, religious narratives, and, especially, genre subjects often illustrating Flemish proverbs or celebrating peasant festivities.

Genre Scenes and Proverbs: Jordaens repeatedly painted scenes illustrating Flemish proverbs and folk traditions, often set during boisterous gatherings. The King Drinks (also known as The Bean King), a subject he painted multiple times, depicts the Twelfth Night feast where the person who finds a bean in their cake is crowned 'king' for the night. These paintings are typically crowded, noisy affairs, filled with ruddy-faced figures eating, drinking, singing, and making merry with uninhibited gusto. Another favorite theme was As the Old Sing, So Pipe the Young, illustrating the idea that children imitate their elders' behavior, often depicted with multiple generations of a family singing and playing music around a table laden with food. These works celebrate Flemish life but often carry a moralizing undertone about moderation or the consequences of bad examples. His skill in rendering textures – food, fabrics, flesh – and capturing expressions of revelry is exceptional. These works stand in contrast to the more refined genre scenes of Dutch contemporaries like Jan Steen, possessing a uniquely Flemish robustness.

Mythological Subjects: Jordaens brought a similar earthiness to his mythological paintings. In The Satyr and the Peasant, based on Aesop's fable, he depicts the satyr's astonishment at the peasant blowing on his soup to cool it and on his hands to warm them, highlighting the contrast between rustic pragmatism and mythical nature. His depictions of The Triumph of Bacchus are riotous processions celebrating wine and revelry, filled with corpulent figures and putti. Even in more dramatic scenes like Prometheus Bound, where the Titan suffers eternal torment, Jordaens emphasizes the physical reality of the suffering, the muscular strain, and the palpable presence of the eagle. Compared to Rubens's often more heroic or idealized mythological figures, Jordaens's gods and heroes seem closer to the common folk of Flanders.

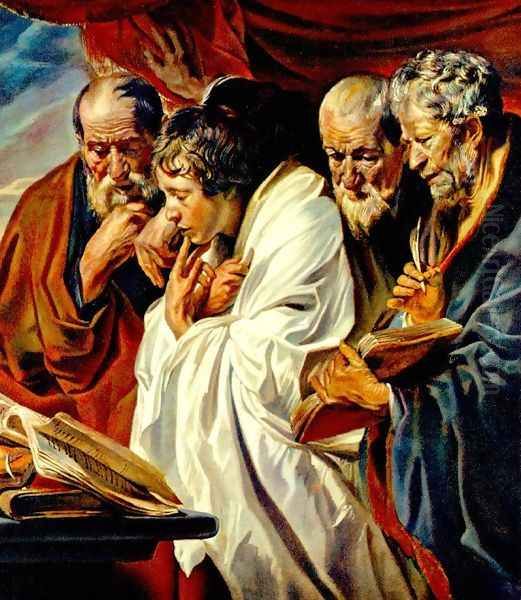

Religious Paintings: Jordaens was a prolific painter of religious subjects, creating numerous altarpieces and devotional works. While adhering to Counter-Reformation requirements for clarity and emotional impact, his religious scenes often retain his characteristic vitality and realism. Works like The Four Evangelists portray the saints as sturdy, thoughtful men engaged in their writing, grounded in a tangible reality. Moses Striking the Rock becomes an opportunity to depict a crowd of thirsty figures eagerly anticipating water, showcasing a range of human reactions. While capable of deep piety, his religious art often emphasizes the human aspects of sacred stories, making them accessible and relatable to the viewer. He continued to receive commissions from Catholic churches even after his later conversion to Protestantism.

Portraits: Although less famous as a portraitist than Van Dyck, Jordaens produced compelling portraits throughout his career. His Self-Portrait with his Wife Catharina van Noort, their Daughter Elizabeth, and a Servant (c. 1621-1622) shows his ability to capture individual likenesses and convey familial relationships within a complex composition. His portraits generally lack the aristocratic refinement of Van Dyck's, often presenting sitters with a more direct, unvarnished presence, consistent with his overall realistic approach. He painted portraits of fellow artists, merchants, and members of his own extensive family.

The Workshop and Production Methods

Like Rubens, Jordaens operated a large and highly organized workshop to cope with the volume of commissions he received, especially after 1640. This was standard practice for successful Baroque artists handling large-scale projects. The workshop likely included apprentices learning the trade, journeyman assistants executing specific parts of paintings under supervision, and potentially specialists in areas like still life or animals, although Jordaens himself was highly proficient in these areas. Frans Snyders, the preeminent animal painter, is known to have collaborated on some works.

The production process for large commissions typically involved Jordaens creating preliminary sketches (modelli) to show the patron and guide his assistants. Once approved, the composition would be transferred to the large canvas, often with assistants blocking in major areas of color or painting background elements, drapery, or architectural settings. Jordaens would then personally execute the most important parts, such as the faces and hands of key figures, and provide the finishing touches to ensure overall quality and coherence. This collaborative method allowed for efficient production without necessarily compromising the artistic vision, as the master's hand and style remained dominant. The sheer number of surviving works attributed to Jordaens and his workshop attests to its productivity.

Jordaens as a Tapestry Designer

From his initial registration as a "waterschilder," tapestry design remained a significant and lucrative part of Jordaens's career. In the 17th century, monumental tapestries were among the most prestigious and expensive forms of decoration, adorning the walls of palaces, churches, and wealthy homes across Europe. Brussels and Antwerp were major centers of tapestry production. Jordaens became one of the leading designers of tapestry cartoons in the Southern Netherlands, rivaling Rubens in this field.

He designed numerous series based on various themes:

Mythology: Such as the Story of Odysseus or the Story of Cupid and Psyche.

History: Including the Story of Alexander the Great and the Life of Charlemagne.

Genre and Proverbs: Series like Scenes from Country Life and illustrations of Flemish proverbs, translating his popular painting themes into the tapestry medium.

Allegory: Allegorical representations of virtues, vices, or concepts like The Riding School.

His cartoons, painted in watercolor or gouache on large sheets of paper or canvas, were known for their clarity, strong compositions, and vibrant colors, which translated well into the woven medium. His robust figures and detailed settings were well-suited to the grand scale of tapestry. Many sets woven after his designs survive in collections across Europe, including the Spanish royal collections, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and numerous other museums, testifying to the widespread demand for his work in this prestigious medium. His success as a tapestry designer significantly contributed to his wealth and fame.

Later Life, Religious Beliefs, and Stylistic Evolution

Jordaens enjoyed a long life and career, remaining active into his eighties. His later works, from the 1650s onwards, sometimes show a subtle shift in style. While retaining his characteristic energy, the color palette occasionally becomes cooler, with greater use of blues, grays, and more subdued tones compared to the warm, golden hues of his earlier periods. Some later works also seem to place a stronger emphasis on moral or didactic themes, although his fundamental approach remains rooted in vigorous realism.

A significant event in his later life was his conversion to Protestantism (specifically, Calvinism) around 1650. This was a risky decision in the staunchly Catholic Spanish Netherlands, where Protestantism was officially suppressed. While Antwerp had a degree of tolerance compared to other regions, open adherence to Calvinism could still lead to persecution. Jordaens appears to have practiced his faith privately for some time. Eventually, his conversion became known, and records indicate he was fined for "scandalous" (heretical) writings or activities.

Despite this, his artistic reputation seems to have remained largely intact. Remarkably, he continued to receive commissions for altarpieces and other works from Catholic patrons and institutions even after his conversion was known. This suggests his artistic skill and established position perhaps outweighed religious objections, or that patrons were willing to overlook his personal beliefs. He also received commissions from Protestant patrons in the Northern Netherlands (Dutch Republic).

His personal life saw tragedy with the early deaths of two of his three sons. His wife, Catharina van Noort, died in 1659. Jordaens himself lived on for nearly two more decades, dying at the advanced age of 85 during an outbreak of a mysterious illness (possibly the 'Antwerp disease' or 'sweating sickness') in Antwerp in 1678. His unmarried daughter Elizabeth, who had lived with him, succumbed to the same illness on the same day. They were buried together under a stone in the Protestant cemetery at Putte, a village just across the border in the Dutch Republic, as burial within Antwerp's consecrated ground was not permitted for Calvinists. Some sources mention limited social engagements in his later years, suggesting perhaps a more withdrawn existence, possibly related to his religious status or simply old age.

Legacy and Influence

Jacob Jordaens stands firmly alongside Rubens and Van Dyck as one of the three most important painters of the Flemish Baroque. While Rubens represented the heroic and dynamic, and Van Dyck the elegant and courtly, Jordaens embodied the vital, earthy, and often humorous spirit of Flanders. His commitment to realism, his focus on genre scenes drawn from everyday life and folklore, and his robust, energetic style created a powerful and distinct artistic voice.

His influence on his immediate contemporaries and pupils in Antwerp was significant, particularly after he became the city's leading master. His popular genre themes were taken up by other artists, including David Teniers the Younger, although Teniers developed a more refined and smaller-scale approach. Jordaens's impact extended beyond Flanders, as his paintings and tapestry designs were known and collected throughout Europe. His work offered a Northern counterpoint to the prevailing Italianate styles.

While his fame perhaps waned somewhat immediately after his death compared to the enduring international renown of Rubens and Van Dyck, his work was rediscovered and appreciated anew in the 18th century. Artists associated with Neoclassicism and early Romanticism found inspiration in his realism and his depiction of strong human emotions. Figures like Jean-Baptiste Greuze in France, known for his moralizing genre scenes, show an affinity with Jordaens's approach. His vigorous brushwork and rich portrayal of everyday life also anticipated aspects of 19th-century Realism.

Today, Jordaens is recognized for his unique contribution to Baroque art. His paintings are celebrated for their sheer vitality, their masterful handling of paint, light, and color, and their insightful, often humorous, portrayal of the human condition. He successfully synthesized influences from Italy (via Rubens and prints) with his native Flemish traditions, creating an art that was both grandly Baroque and deeply personal. His works remain highlights in major museums worldwide, offering a powerful and engaging vision of 17th-century Flemish life and art. His ability to imbue religious and mythological subjects with tangible reality, and to elevate scenes of everyday life to monumental status, secures his place as a truly original master.