Cornelis Pietersz. Bega stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure within the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age art. Active during the mid-seventeenth century primarily in the vibrant artistic center of Haarlem, Bega carved a niche for himself as a painter and etcher of genre scenes. His work, deeply influenced by his master Adriaen van Ostade, focused on the lives of ordinary people – peasants, artisans, and tavern-goers – depicted with a keen eye for detail, psychological depth, and atmospheric nuance. Though his career was tragically cut short, Bega left behind a body of work that continues to fascinate scholars and art lovers, offering intimate glimpses into the social fabric of his time. His journey from a promising student to a recognized master, his travels, his technical proficiency, and the eventual recognition of his artistic contributions paint a picture of a dedicated artist navigating the dynamic world of seventeenth-century Dutch art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Haarlem

Cornelis Pietersz. Bega was born into an environment steeped in art and craft in Haarlem around 1631 or 1632. His family background provided both financial stability and artistic lineage, factors that undoubtedly shaped his path. His father, Pieter Jansz. Begijn, was a respected goldsmith and sculptor, indicating a household familiar with skilled craftsmanship and aesthetic principles. More significantly, his mother, Maria, was the daughter of the highly esteemed Haarlem Mannerist painter Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, one of the leading artists of the previous generation. This connection placed the young Bega within a prominent artistic dynasty, likely exposing him to art discussions, collections, and the general milieu of Haarlem's thriving artistic community from an early age.

Haarlem itself was a crucible of artistic innovation during the Dutch Golden Age, particularly renowned for its landscape and genre painters. It was in this stimulating environment that Bega sought formal training. He became a pupil of Adriaen van Ostade, a leading master of peasant genre scenes. Ostade's studio was a hub for learning the popular style of depicting low-life interiors, tavern brawls, and rustic family life. Under Ostade's tutelage, Bega would have learned the fundamentals of composition, figure drawing, the handling of paint, and, crucially, the empathetic yet often humorous observation of common folk that characterized his master's work. This apprenticeship laid the essential groundwork for Bega's own artistic preoccupations and stylistic development.

Travels and Professional Milestones

Like many ambitious artists of his time, Bega sought to broaden his horizons beyond his native city. Between 1653 and 1654, he embarked on a significant journey through parts of Germany, Switzerland, and possibly France. This "Grand Tour," albeit perhaps more modest than those undertaken by aristocrats, was a crucial period of exposure and development. He traveled in the company of fellow artists, most notably Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne, who meticulously documented their journey in a diary. This diary provides valuable insights into their travels, observations, and the artistic camaraderie they shared. Other companions on this trip likely included artists such as Dirck Helmbreker. Such journeys exposed artists to different landscapes, cultures, artistic styles, and potential patrons, enriching their visual vocabulary and professional networks.

Upon his return to Haarlem, Bega took a decisive step in establishing his professional career. In 1654, he was admitted into the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. Membership in the guild was essential for any artist wishing to practice independently, take on pupils, or sell their work legally within the city. It signified professional recognition and adherence to the standards and regulations of the local artistic community. Records show Bega re-registered with the guild in 1662, indicating his continued active status as a professional artist in Haarlem throughout his relatively brief career. This formal integration into the city's artistic infrastructure marked his transition from student to recognized master.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Cornelis Bega's artistic output is firmly rooted in the genre tradition, focusing predominantly on scenes of everyday life, particularly among the lower and middle classes. His subjects often include peasants relaxing or carousing in rustic interiors, drinkers gathered in dimly lit taverns, women engaged in domestic tasks, artisans at work, and occasionally more enigmatic figures like alchemists or scholars in their studies. While clearly indebted to his teacher Adriaen van Ostade, Bega developed a distinct artistic personality. His early works sometimes exhibit a rougher handling, but his mature style is characterized by greater refinement, smoother brushwork, and often a more monumental approach to his figures compared to Ostade's typically smaller-scale compositions.

Bega possessed a remarkable ability to capture the atmosphere of interior spaces, often employing a subtle chiaroscuro effect where light filters in from a window or door, illuminating parts of the scene while leaving others in deep shadow. This use of light and shadow not only creates visual interest but also enhances the mood and psychological intimacy of his scenes. He excelled in rendering textures – the rough wool of a peasant's coat, the gleam of a pewter jug, the worn wood of a table. His figures, while often types, are imbued with a sense of individual presence and emotion. He captured gestures, expressions, and interactions with sensitivity, revealing the quiet dramas and simple pleasures of daily existence. His palette often favors warm, earthy tones – browns, ochres, and reds – contributing to the cozy or sometimes somber ambiance of his interiors.

While many of his scenes depict moments of leisure or sociability, Bega did not shy away from the less savory aspects of life. His depictions of taverns sometimes hint at dissolution, and his portrayals of figures like alchemists tap into a contemporary fascination with science, pseudo-science, and the pursuit of hidden knowledge. Through his careful observation and nuanced portrayal, Bega's work offers a valuable window into the social realities and cultural preoccupations of the Dutch Republic in the mid-seventeenth century. He moved beyond mere anecdote to explore the character and condition of his subjects with considerable empathy.

Representative Works: Paintings and Prints

Several works stand out as representative of Bega's artistic achievements. Among his paintings, Tavern Scene (various versions exist) exemplifies his skill in depicting lively group interactions within atmospheric interiors. These works often feature multiple figures engaged in drinking, smoking, conversation, or music-making. Bega masterfully orchestrates these complex compositions, using light to highlight key figures and expressions, creating a palpable sense of conviviality or sometimes tension. The detailed rendering of objects and textures adds to the realism and richness of the scene.

Another significant theme explored by Bega is that of the scholar or alchemist. The Alchemist (again, multiple versions exist) typically shows a solitary figure engrossed in his work amidst the clutter of his laboratory – furnaces, alembics, books, and mortars. These paintings capture the intense concentration of the practitioner and the mysterious allure of the alchemical pursuit, often using dramatic lighting to enhance the secretive atmosphere. These works reflect a broader seventeenth-century interest in scientific inquiry and the blurred lines between empirical investigation and esoteric practices.

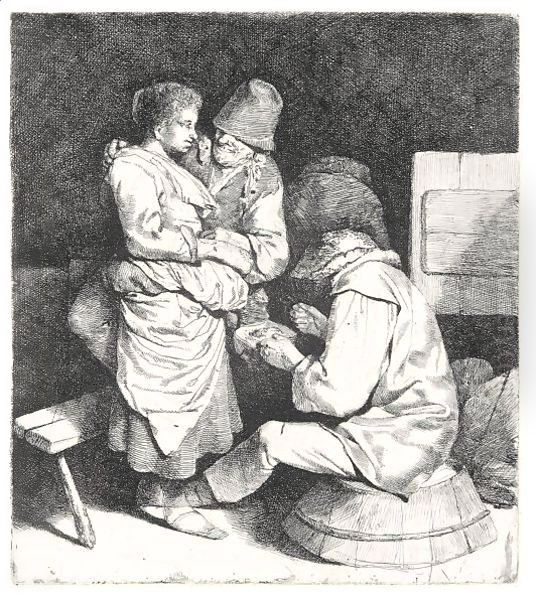

Bega was also a highly accomplished printmaker, primarily working in etching. His prints often explore similar themes to his paintings but demonstrate a distinct graphic sensibility. Three Peasants by the Chimney is a fine example of his etched work, showcasing his ability to create a sense of warmth and intimacy through line and tone. He employed techniques like dense cross-hatching and possibly re-biting the plate to achieve rich darks and varied textures, lending his prints a painterly quality. Other notable prints include The Inn and The Assembly at the Inn, which further demonstrate his mastery of group composition and atmospheric effects within the constraints of the etching medium. His graphic work was influential and highly regarded both during his lifetime and after.

Prowess in Printmaking

The Dutch Golden Age witnessed an explosion in printmaking, with etching becoming a particularly favored medium for artists seeking wider dissemination of their work and exploring graphic possibilities. Cornelis Bega was a significant contributor to this field, producing around thirty-eight etchings during his career. His prints are notable for their technical skill, atmospheric depth, and thematic consistency with his paintings. He demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the etching process, manipulating line width, density, and biting times to achieve a wide range of tonal values and textures.

His use of cross-hatching is particularly adept, allowing him to model forms convincingly and create deep, velvety shadows that contribute significantly to the mood of his scenes. Works like The Young Hostess or Man Caressing the Young Hostess showcase his ability to handle intimate two-figure compositions within the print medium, capturing subtle interactions and expressions. Some scholars have also noted his potential interest in experimental techniques, possibly including early forms of monochrome woodcut or unique combinations of print processes, although etching remained his primary graphic medium.

Bega's prints were popular and circulated among collectors. They helped to solidify his reputation and spread his artistic vision beyond the circle of those who could afford his paintings. His graphic oeuvre stands alongside his paintings as a testament to his versatility and his mastery of conveying the nuances of light, texture, and human emotion through both brush and burin. The quality and sensitivity of his etchings place him among the more accomplished Dutch printmakers of his generation, following in the footsteps of masters like Rembrandt van Rijn, though focusing on his characteristic genre subjects.

Contemporaries, Connections, and Influence

Cornelis Bega operated within the dynamic and interconnected art world of Haarlem and the broader Dutch Republic. His most formative connection was undoubtedly with his teacher, Adriaen van Ostade. He absorbed much from Ostade but also forged his own path. Adriaen's brother, Isaac van Ostade, was also a prominent genre painter in Haarlem, and Bega would certainly have been familiar with his work, which often focused on outdoor scenes and landscapes with figures.

His travel companions, Vincent van der Vinne and Dirck Helmbreker, were fellow Haarlem artists with whom he shared experiences and likely exchanged ideas. Within Haarlem, he would have known and interacted with numerous other painters. The Guild of St. Luke provided a formal structure for these interactions. Artists potentially sharing models or studio spaces, or simply moving in the same professional circles, included figures like the cityscape painter Gerrit Berckheyde, the portrait and genre painter Leendert van der Cooghen, and the skilled engraver Cornelis Visscher. The mention of "Salomon" might refer to Salomon de Bray, a versatile Haarlem artist, or perhaps Salomon Koninck, active in nearby Amsterdam.

Bega's work also shows awareness of, and perhaps dialogue with, other leading genre painters of the time. His interest in slightly more complex narratives and psychological interactions brings him closer in spirit to Jan Steen, another major figure active partly in Haarlem. Indeed, some sources suggest that Steen, known for his lively and often moralizing scenes, imitated aspects of Bega's style, particularly his dramatic characterizations. Other contemporaries in Haarlem whose work Bega would have known include Cornelis Dusart (also an Ostade pupil), Jan de Groot, and Evert Oudendijck. Even the great Frans Hals was still active in Haarlem during Bega's early years. This network of teachers, peers, potential collaborators, and competitors formed the rich context in which Bega developed his art. His influence extended beyond his death, with his compositions and figure types being emulated by later artists.

Later Life and Untimely Death

Despite his evident talent and growing reputation, Cornelis Bega's career was tragically brief. He died in Haarlem on August 27, 1664, at the young age of only about 32 or 33. Contemporary sources, including the diary of his travel companion Vincent van der Vinne, indicate that his death was likely caused by the plague (pest), which periodically ravaged European cities during this period. Haarlem suffered outbreaks, and Bega appears to have been one of its victims.

His premature death cut short a promising artistic trajectory. At the time of his passing, he was a fully established master, a member of the guild, and producing mature works that demonstrated considerable skill and sensitivity. One can only speculate on how his style might have further evolved had he lived longer. He was buried in the graveyard of the St. Bavokerk (Grote Kerk) in Haarlem, reportedly in a plot associated with the Guild of St. Luke or possibly his grandparents, a final connection to the city and the artistic community that had shaped his life and career.

Legacy and Art Historical Reception

The assessment of Cornelis Bega's importance in art history has evolved over time. While recognized in his own era, subsequent centuries sometimes relegated him to the status of a minor follower of Adriaen van Ostade. Some early accounts or interpretations may have been colored by anecdotal information regarding his mother's background, which some sources describe as "disgraceful," potentially casting a shadow over his social standing and, consequently, his historical reputation. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his unique contributions and artistic merits.

His technical proficiency, both in painting and etching, is now widely acknowledged. His ability to infuse genre scenes with psychological depth and atmospheric subtlety distinguishes his work. While influenced by Ostade, his tendency towards larger figures, more focused compositions, and a slightly more serious or contemplative mood in many works sets him apart. His paintings and prints became desirable collectors' items. For instance, records show works being acquired by notable collectors like Sir George Donaldson in the early 20th century, and auction results, such as a reported $170,000 sale for a Village Square scene, indicate sustained market interest and appreciation for his art.

Furthermore, his influence on other artists, particularly Jan Steen, highlights his significance within the Dutch Golden Age network. Exhibitions dedicated to or including his work, such as those held in institutions like the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum, have helped to re-evaluate his position and showcase the quality of his output to a wider audience. Today, Cornelis Bega is regarded not merely as a follower, but as an independent master who made a distinct and valuable contribution to Dutch genre painting and printmaking. He is appreciated for his sensitive portrayal of everyday life, his technical finesse, and his ability to capture the quiet dignity and complex humanity of his subjects.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Seventeenth-Century Life

Cornelis Pietersz. Bega remains a compelling figure in the study of Dutch Golden Age art. Emerging from an artistic family in the vibrant center of Haarlem, he honed his skills under a leading master, Adriaen van Ostade, yet developed a distinctive voice. His travels broadened his perspective, and his membership in the Guild of St. Luke solidified his professional standing. Through his paintings and etchings, Bega offered intimate, empathetic, and technically accomplished views into the lives of ordinary Dutch people – in their homes, workshops, and taverns. He masterfully employed light, texture, and composition to create atmospheric and psychologically resonant scenes.

Though his life was cut short by plague, his legacy endured. He influenced contemporaries like Jan Steen and left behind a body of work that continues to be valued by collectors and studied by art historians. The evolution of his critical reception, moving from the shadow of his master and potential social prejudice to recognition as a significant artist in his own right, underscores the enduring quality of his vision. Cornelis Bega's art provides invaluable insight into the social fabric and artistic currents of the seventeenth-century Netherlands, capturing moments of labor, leisure, and contemplation with a quiet intensity that still speaks to viewers today. He stands as a testament to the depth and diversity of talent that flourished during the Dutch Golden Age.