The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands. Amidst the towering figures known for portraiture, history painting, and landscape, Adriaen Jansz. van Ostade carved a distinct and enduring niche for himself. Born in Haarlem on December 10, 1610, and passing away in the same city on May 2, 1685, Ostade became one of the most significant and prolific genre painters of his time, dedicating his long career to depicting the everyday lives of peasants, artisans, and the lower classes of Dutch society. His work offers an invaluable, often humorous, and increasingly empathetic window into a world far removed from the wealthy merchants often portrayed by his contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Adriaen van Ostade entered the world in Haarlem, a vibrant center for art and commerce. His father, Jan Hendricx van Ostade, hailed from the village of Ostade near Eindhoven, which provided the family surname adopted by both Adriaen and his younger brother Isack, who would also become a notable painter. Little is documented about Adriaen's earliest years, but his artistic path became clear by 1627 when he is recorded as a pupil of the renowned Haarlem portraitist Frans Hals.

Studying under Hals, a master known for his lively brushwork and ability to capture fleeting expressions, likely provided Ostade with a foundational understanding of depicting human figures with vitality. Although Ostade's subject matter and detailed finish would eventually diverge significantly from Hals's broader style, the early exposure to such a dynamic painter may have instilled in him an appreciation for capturing the energy of human interaction, a quality evident even in his small-scale genre scenes.

Influences and Artistic Milieu

While Frans Hals was his formal teacher, the Flemish painter Adriaen Brouwer arguably exerted a more profound influence on Ostade's early artistic direction. Brouwer, who also worked in Haarlem for a period around the time Ostade was developing his style, specialized in low-life scenes, often depicting peasants carousing, brawling, and gambling in dimly lit taverns. Ostade's early works, particularly those from the 1630s, clearly echo Brouwer's themes and compositions, often featuring coarse figures engaged in boisterous, sometimes crude, activities.

These early paintings frequently employ a somewhat monochromatic palette, emphasizing browns and grays, and utilize strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten the drama, another characteristic shared with Brouwer. However, even in these formative years, Ostade began to distinguish himself with a finer technique and a less biting, more observational tone than the often-harsh satire found in Brouwer's work.

Another towering figure whose influence can be discerned, perhaps more indirectly, is Rembrandt van Rijn. Although working primarily in Leiden and later Amsterdam, Rembrandt's mastery of light and shadow, his psychological penetration of subjects, and his interest in depicting ordinary people resonated throughout the Dutch art world. Ostade's sophisticated handling of light, particularly in his later works where it creates atmosphere and focuses attention within interiors, suggests an awareness and absorption of Rembrandtesque principles, adapted to his own distinct subject matter.

The Haarlem Guild and Professional Life

Adriaen van Ostade's professional integration into the Haarlem art scene was formalized in 1634 when he joined the city's Guild of Saint Luke. This membership was essential for artists wishing to practice independently, take on pupils, and sell their work legally. Ostade became an active and respected member of the Guild, serving as one of its directors, or hoofdmannen, in 1647 and again in 1662. These positions indicate his high standing among his peers and his involvement in the governance of the local artistic community.

Haarlem itself was a thriving artistic hub during this period. Besides Hals, the city was home to notable still life painters like Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz. Heda, landscape specialists such as Jacob van Ruisdael (though he also worked elsewhere), and other genre painters. This environment fostered both competition and collaboration, pushing artists to refine their skills and specialize. Ostade remained based in Haarlem for virtually his entire life, finding ample inspiration and a ready market for his chosen specialty.

Subject Matter: The World of the Dutch Peasant

Ostade's primary contribution to Dutch art lies in his detailed and extensive portrayal of peasant life. His oeuvre encompasses a wide range of scenes: smoky tavern interiors filled with drinkers, card players, and smokers; humble cottage rooms where families gather, women work, and children play; village schoolrooms bustling with unruly pupils; the workshops of artisans like weavers or cobblers; and outdoor scenes depicting village fairs, itinerant musicians, or figures relaxing outside their homes.

His figures are rarely idealized. He depicted peasants with honesty, showing their coarse clothing, simple furnishings, and unrefined manners. Yet, his portrayal evolved significantly over his career. Early works often emphasized the boisterous, chaotic, and sometimes crude aspects of peasant life, aligning with a common urban stereotype. Figures might be shown drunk, arguing, or engaging in rough-and-tumble activities, sometimes with a satirical or moralizing undertone.

However, from the 1640s onwards, Ostade's approach softened. His depictions became more tranquil, orderly, and sympathetic. He increasingly focused on quieter domestic scenes, the pleasures of family life, simple work, and peaceful leisure. The humor remained, but it became gentler, less about caricature and more about affectionate observation of human nature. This shift may reflect personal changes, including his later conversion to Catholicism, or perhaps a changing market preference towards more idyllic portrayals of rural life.

Evolution of Style: Light, Color, and Detail

Parallel to the thematic shift, Ostade's painterly style also underwent a noticeable evolution. His early works, influenced by Brouwer, often feature sharp contrasts, a limited, earthy palette, and somewhat looser brushwork. The figures can appear almost caricatured, emphasizing expressive, sometimes grotesque, features.

As his career progressed, his technique became more refined and his handling of light and color grew increasingly sophisticated. He developed a mastery of chiaroscuro, using light not just for dramatic effect but to create a palpable sense of atmosphere within his interiors. Light often streams in from a window or door, illuminating a central group of figures or highlighting specific details, while surrounding areas recede into warm, transparent shadow.

His color palette also expanded and grew warmer, incorporating richer reds, blues, and greens alongside the predominant earth tones. His brushwork became finer, allowing for meticulous attention to detail in rendering textures – rough-hewn wood, coarse fabrics, earthenware pottery, and cluttered domestic objects. Despite the small scale of many of his paintings, they are often packed with carefully observed details that enhance their realism and narrative richness. This detailed approach aligns him somewhat with the fijnschilders (fine painters) like Gerard Dou of Leiden, although Ostade's touch remained generally freer.

Mastery Across Mediums: Painting, Etching, and Drawing

Adriaen van Ostade was a remarkably versatile and prolific artist. While best known for his oil paintings, estimated to number around 800 (though attributions vary), he was also a highly accomplished etcher and draftsman. His output includes approximately 50 etchings, numerous watercolors, and a large body of preparatory drawings.

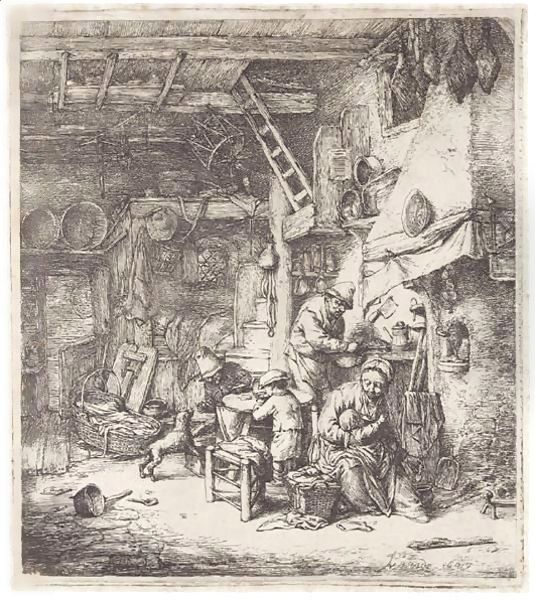

His etchings are particularly significant. He approached the medium with the same care and skill as his painting, translating his characteristic subjects and compositions into intricate linear work. His etchings display a remarkable control over tone and texture, achieved through dense networks of lines and careful biting of the copper plate. Works like The Family (1647) showcase his ability to render intimate domestic scenes with warmth and detail in the etched medium.

Ostade's etchings were highly popular and circulated widely, contributing significantly to his fame both within the Netherlands and abroad. They were often based on his own paintings or drawings, allowing his compositions to reach a broader audience. Many impressions of his plates exist, sometimes in different states as he reworked the plates, providing insight into his working process. His drawings, often executed in pen and ink with wash or chalk, served as preparatory studies but are also appreciated as artworks in their own right, showcasing his fluid draftsmanship and keen observational skills.

Representative Works

Several works stand out as representative of Ostade's style and thematic concerns:

Peasants in an Inn (c. 1662, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London): This painting exemplifies Ostade's mature style. It depicts a relatively orderly tavern interior, bathed in soft light entering from the left. Peasants are shown conversing, drinking, and smoking in a relaxed atmosphere. The figures are individualized, the details of the setting are carefully rendered, and the overall mood is one of convivial tranquility, far removed from the boisterousness of his earlier tavern scenes.

The Village Musicians (c. 1640s): Several versions of this theme exist. Typically, they show itinerant musicians, perhaps playing a fiddle or hurdy-gurdy, entertaining peasants outside an inn or cottage. These works capture the simple pleasures of rural life and Ostade's interest in everyday entertainment and social interaction.

Skaters (c. 1650s): While primarily known for interiors, Ostade also depicted outdoor scenes. His paintings of skaters on frozen canals or ponds capture a quintessential Dutch winter activity, often including numerous small figures engaged in various pursuits on the ice, showcasing his skill in composing lively multi-figure scenes.

The Alchemist (1661, National Gallery, London): This work represents a slightly different theme, depicting an alchemist in his cluttered laboratory. It combines Ostade's skill in rendering detailed interiors with an element of scholarly pursuit, though often treated with a degree of satire regarding the futility of the alchemist's quest.

The Painter in his Studio (c. 1663, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden): Offering a glimpse into the artist's world, this painting shows a painter (possibly a self-portrait or an idealized representation) at his easel in a rustic studio. It highlights Ostade's ability to create complex interior spaces filled with the tools and paraphernalia of the trade, bathed in his characteristic warm light.

The Family (Etching, 1647): This celebrated etching portrays a humble family – father, mother, baby, and another child – gathered near a hearth in a simple interior. It is a prime example of Ostade's later, more sympathetic portrayal of peasant domesticity and his mastery of the etching medium to convey warmth and intimacy.

Students and Workshop Practice

As a respected master in the Haarlem Guild, Adriaen van Ostade attracted several pupils to his studio. The most notable was his own younger brother, Isack van Ostade (1621-1649). Isack initially worked in Adriaen's style, focusing on similar interior scenes. However, Isack soon developed his own distinct specialty, becoming particularly known for his lively outdoor scenes, especially winter landscapes with figures, before his tragically early death.

Another significant pupil, albeit possibly for a shorter period, was the famous genre painter Jan Steen (c. 1626-1679). Steen, known for his boisterous and often moralizing depictions of chaotic households, likely absorbed aspects of Ostade's approach to genre painting, though Steen developed a much broader, more narrative, and overtly comical style.

Other documented pupils include Cornelis Pietersz. Bega (c. 1631-1664), whose work closely resembles Ostade's in subject and style, Michiel van Musscher (1645-1705), who later turned more towards portraiture, and Cornelis Dusart (1660-1704). Dusart was perhaps Ostade's closest follower, inheriting his master's drawings and copper plates and continuing to produce peasant genre scenes in a style very similar to Ostade's later work well into the late 17th century.

Connections with Contemporaries

Ostade's long career placed him at the heart of the Dutch Golden Age, interacting with and responding to the work of numerous contemporaries beyond his direct teachers and pupils. His relationship with Adriaen Brouwer was formative. His adaptation of Rembrandtesque light suggests an awareness of the Amsterdam master's innovations.

Comparisons can be drawn with other genre painters. While Gerard Dou in Leiden perfected the highly polished fijnschilder technique, Ostade maintained a slightly looser, more painterly approach. Unlike Pieter de Hooch or Johannes Vermeer, who often depicted serene domestic scenes in more affluent bourgeois settings, Ostade remained focused on the rural and lower-class milieu. Gabriel Metsu, another painter of genre scenes, shared Ostade's interest in detailed interiors but often depicted interactions with a greater sense of narrative or psychological subtlety. Ostade's work, alongside that of these and other artists, contributed to the rich tapestry of Dutch genre painting, which explored myriad facets of 17th-century life.

Personal Life

Details about Adriaen van Ostade's personal life are relatively scarce compared to the extensive record of his artistic output. It is known that he married Machteltje Pietersdr. in Haarlem in 1638, but she sadly passed away just a few years later, in 1642. He remained a widower for a considerable time before marrying Anna Ingels in 1657. Sources suggest this second marriage brought him considerable wealth. Together, they had a daughter, Johanna Maria, who was baptized in 1660.

Later in life, possibly around the time of his second marriage, Ostade converted to Catholicism. This was somewhat unusual in the predominantly Protestant Dutch Republic, although Haarlem had a significant Catholic minority. Some art historians speculate that this conversion may have influenced the shift towards more sympathetic and harmonious depictions in his later work, moving away from the sometimes harsh satire of his earlier period. He continued to live and work in Haarlem until his death in 1685, being buried in the Sint-Bavokerk (St. Bavo's Church).

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Adriaen van Ostade enjoyed considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His paintings and etchings were sought after by Dutch collectors and also found an early market abroad. His influence extended through his pupils, particularly Cornelis Dusart, who continued his style, and through the wide dissemination of his compositions via etchings.

His reputation endured after his death. Throughout the 18th century, his works remained highly prized, particularly in France and England. His depictions of rustic life resonated with Enlightenment ideals of nature and simplicity, and his technical skill was admired. His work may have indirectly influenced later genre painters, including figures like the English satirist William Hogarth, who also depicted scenes of everyday life, albeit with a much sharper critical edge.

Today, Adriaen van Ostade is firmly established as one of the leading genre painters of the Dutch Golden Age. His works are held in major museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the National Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. His paintings and etchings continue to be studied for their artistic merit, their technical brilliance, and the invaluable insight they provide into the social fabric of the 17th-century Netherlands. He remains celebrated for his ability to capture the essence of everyday life – its hardships, its simple pleasures, its humor, and its humanity – with enduring skill and evolving empathy. His vast oeuvre stands as a testament to a long life dedicated to observing and chronicling the world of the common man during a remarkable era in art history.