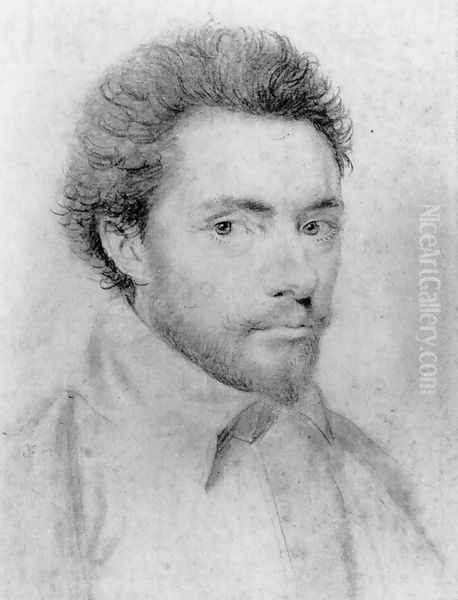

Daniel Dumonstier (1574-1646) stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of French art, particularly celebrated for his exquisite portraiture executed with remarkable finesse in colored chalks. Born into an era of artistic transition and flourishing in Paris, Dumonstier not only inherited a profound artistic legacy but also carved his own distinct niche, becoming one of the most sought-after portraitists of his time. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the cultural, political, and intellectual currents of 17th-century France, reflecting the tastes of a discerning clientele that included royalty, nobility, and prominent figures of the age.

An Artistic Dynasty: The Dumonstier Family Heritage

The name Dumonstier was already well-established in French artistic circles long before Daniel made his mark. The family was a veritable dynasty of artists, active from the 16th to the 18th centuries, producing painters, engravers, designers, goldsmiths, and sculptors. This rich familial environment undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping Daniel's artistic inclinations and providing him with foundational training.

His grandfather, Geoffroy Dumonstier (c. 1500/1510–1573), was a multifaceted artist, known as a painter, engraver, and illuminator, who served King Francis I and Henry II. He was involved in decorative projects at the Palace of Fontainebleau, a crucible of French Renaissance art. Daniel's father, Côme Dumonstier (c. 1545 – before 1605), was also a respected portrait painter, ensuring that the tradition of capturing likenesses was passed down directly. Furthermore, Daniel's uncles, Étienne Dumonstier I (c. 1540–1603) and Pierre Dumonstier I (c. 1545 – c. 1610), were highly regarded portraitists. Étienne, in particular, was a principal portrait painter to the French court, serving figures like Catherine de' Medici. This lineage provided Daniel not only with technical instruction but also with invaluable connections to the highest echelons of French society. His brother, Nicolas Dumonstier (c. 1570/75 - 1630/31), also pursued a career as a portrait painter, further cementing the family's artistic prominence.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris in 1574, Daniel Dumonstier was immersed in art from his earliest years. While specific details of his formal apprenticeship are scarce, it is almost certain that his primary training occurred within the family workshop, under the tutelage of his father Côme and perhaps his illustrious uncles. He would have learned the meticulous techniques of drawing and the nuanced application of colored chalks, a medium in which the Dumonstier family excelled.

The artistic environment of late 16th-century France was still heavily influenced by the legacy of the School of Fontainebleau and the refined portraiture style established by artists like Jean Clouet (c. 1480–1541) and his son François Clouet (c. 1510–1572). The Clouets had popularized the "crayon portrait" – detailed chalk drawings, often in black and red (deux crayons) or with additional colors (trois crayons) – which served both as preparatory studies and as finished works of art. Daniel Dumonstier would become a master of this tradition, elevating it to new heights of psychological penetration and technical brilliance in the early 17th century.

The Ascent of a Court Portraitist

Daniel Dumonstier's talent did not go unnoticed. He quickly gained favor at the French court, serving successive monarchs and their entourages. He was appointed Peintre et Valet de Chambre du Roi (Painter and Valet de Chambre to the King), a prestigious position that signified royal patronage and provided both status and a regular income. He served King Henry IV and later King Louis XIII.

His standing was further solidified in 1602 when he married Geneviève Balifre, the daughter of Claude Balifre, who was the director of the king's chamber music. This marriage connected him to another influential sphere within the court. A significant mark of his official recognition came in 1622 when Louis XIII granted him lodging in the Louvre Palace. This privilege was reserved for esteemed artists and craftsmen in royal service, placing him at the very heart of France's artistic and cultural life. His clientele expanded to include the highest nobility, influential ministers like Cardinal Richelieu, and other celebrated personalities of the era.

Master of the Crayon: Dumonstier's Signature Style

Dumonstier's reputation rests primarily on his mastery of the colored chalk portrait. He typically worked on unprimed paper, a demanding surface that required unerring precision, as mistakes were difficult to correct. His technique was characterized by its delicacy and its extraordinary ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also the sitter's personality and inner state.

He inherited the French classical style but infused it with a heightened sense of realism and psychological depth. While some critics of his time, or later, may have found his work to lack the bold linearity or idealized abstraction of other schools, Dumonstier's strength lay in his subtle modeling, his nuanced use of color, and his keen observation of individual features. He paid meticulous attention to the texture of skin, the gleam in an eye, the subtle curve of a lip, and the intricate details of contemporary costume and hairstyles. His portraits often convey a sense of immediacy and presence, as if the sitter might speak or turn their head at any moment.

His palette, while often based on the traditional black, red, and white chalks, could be expanded with a range of subtle flesh tones, blues, browns, and other colors to render fabrics and accessories with remarkable verisimilitude. The way he used light and shadow was particularly adept, creating a sense of volume and bringing forth the character of his subjects. This combination of realistic depiction and an inherent elegance defined his contribution to the evolution of French portraiture.

Notable Portraits and Subjects

Many of Daniel Dumonstier's works are preserved in prestigious collections, including the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Musée du Louvre in Paris, as well as the Musée Condé in Chantilly. While specific titles often vary or are descriptive (e.g., "Portrait of a Man," "Portrait of a Lady"), his sitters were the luminaries of his age.

He created memorable portraits of King Louis XIII and his wife, Anne of Austria. His depictions of powerful figures like Cardinal Richelieu would have been significant commissions, capturing the astute and commanding presence of the King's chief minister. Beyond royalty and high-ranking clergy, Dumonstier portrayed a wide array of courtiers, military leaders, intellectuals, and fashionable members of the aristocracy. These portraits serve as invaluable historical documents, offering insights into the appearance, attire, and social standing of the French elite during the first half of the 17th century.

One can imagine the sittings: the artist, with his array of chalks, observing his subject intently, engaging them in conversation perhaps, to capture not just their features but a spark of their spirit. The intimacy of the chalk medium, compared to the more formal and laborious process of oil painting, allowed for a more direct and often more revealing portrayal. His works stand as a testament to his skill in navigating the delicate balance between flattering his sitters and rendering a truthful likeness.

Beyond the Easel: A Man of Intellect and Curiosity

Daniel Dumonstier was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was a man of considerable intellect and diverse interests. He was known to be a collector, and his "cabinet of curiosities" (cabinet de curiosités) in Paris was reportedly famous, attracting many distinguished visitors. These collections, popular among the educated elite of the time, typically housed a wide array of objects: natural specimens, scientific instruments, antiquities, exotic artifacts, and works of art. Dumonstier's cabinet suggests a mind engaged with the burgeoning scientific inquiries and the expanding global awareness of the 17th century.

His interests extended to music, and he was known to be fond of musical instruments. This appreciation for music might have been fostered by his marriage into the Balifre family, who were deeply involved in the court's musical life.

More controversially, Dumonstier held strong, and at times non-orthodox, religious and political views. He is recorded as having preached at the Port-Royal church in 1625, and his ideas apparently caused some stir. He was associated with the parti dévot (devout party), a faction within French Catholicism that was often critical of what they perceived as overly pragmatic or insufficiently zealous religious policies, particularly those that might favor Protestant interests in Europe. His outspokenness or involvement in these circles eventually led to his imprisonment in the Château de Vincennes from 1638 until 1643, a significant interruption in his later career. This episode highlights the often-perilous intersection of art, religion, and politics in 17th-century France.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of 17th Century France

Daniel Dumonstier worked during a vibrant period in French art. While he specialized in crayon portraits, the broader artistic landscape was being shaped by various influences. The reigns of Henry IV and Louis XIII saw a concerted effort to re-establish Paris as a major European cultural center after the turmoil of the Wars of Religion.

Among his direct contemporaries in France was Martin Fréminet (1567–1619), who, after a long period in Italy, returned to work for Henry IV, notably on the Trinity Chapel at Fontainebleau, bringing a Mannerist-influenced style. Daniel Rabel (1578–1637), a versatile artist known for flower paintings, miniatures, and designs for ballets, was another figure active during this time, and some sources suggest collaborations or shared circles of influence, particularly under Henry IV.

The dominant force in French painting during the first half of the 17th century was arguably Simon Vouet (1590–1649). After a formative period in Italy, Vouet returned to Paris in 1627 and introduced a vibrant, Italianate Baroque style that transformed French painting, moving away from the lingering Mannerism of the Fontainebleau school. While Vouet worked primarily in large-scale oil paintings for religious and mythological subjects, his influence was pervasive.

Another towering figure in French portraiture was Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674). Of Flemish origin but active in Paris from 1621, Champaigne developed a sober, deeply insightful, and psychologically profound style of portraiture, often associated with the Jansenist movement centered at Port-Royal. His portraits, typically in oil, offer a fascinating contrast to Dumonstier's chalk works, though both artists aimed for a truthful and dignified representation of their sitters.

Other major French artists of the era, though working in different genres or largely abroad, contributed to the overall artistic climate. Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) and Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) were the leading exponents of French Classicism in landscape and historical painting, though they spent most of their careers in Rome. Their ideals of order, harmony, and intellectual rigor resonated within French artistic thought. Georges de La Tour (1593–1652), working in Lorraine, developed a unique Caravaggesque style characterized by dramatic chiaroscuro and quiet spiritual intensity.

While Dumonstier's primary medium differed, he operated within this dynamic environment. His focus on the intimate and personal nature of the crayon portrait provided a distinct counterpoint to the grander ambitions of history painters or the more formal oil portraits. His work can also be seen in the context of earlier masters like Jean Perréal (c. 1455-c. 1530), who also excelled in royal portraiture, and the aforementioned Clouets, who truly established the crayon portrait as a significant genre in France. The tradition of fine draughtsmanship he upheld would be continued by later artists, including the celebrated engraver and portraitist Robert Nanteuil (c. 1623–1678), who also produced remarkable pastel portraits.

Internationally, the towering figures of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) were revolutionizing portraiture in Northern Europe, with Van Dyck, in particular, establishing a model of aristocratic elegance that would influence court portraiture across the continent. While Dumonstier's style remained distinctly French, the broader European context underscores the importance and prestige attached to portraiture during this period.

Critical Reception and Legacy

During his lifetime, Daniel Dumonstier was highly esteemed, as evidenced by his court appointments, prestigious clientele, and the privilege of Louvre accommodation. His works were valued for their likeness, their refinement, and their psychological acuity. The very nature of crayon portraits – often more personal and less formal than large oil paintings – meant they were cherished by collectors and often kept in albums or private chambers.

While the grand narratives of Baroque oil painting sometimes overshadow the more intimate art of chalk portraiture in general art historical surveys, Dumonstier's contribution is undeniable. He represents the apogee of a specifically French tradition. His portraits are not merely faces; they are documents of an age, capturing the personalities, fashions, and social hierarchies of the courts of Henry IV and Louis XIII.

Some later assessments, as noted in the provided information, occasionally pointed to a perceived lack of "precision and clarity of line" when perhaps compared to more rigidly classical draughtsmen. However, this critique might overlook Dumonstier's intentional focus on achieving a subtle, blended realism and capturing the "living" quality of his sitters, rather than adhering to a more abstract or linear ideal. His emphasis was on the interplay of light, color, and texture to convey both physical presence and individual character.

The unfortunate loss of some works, such as those reportedly in the collection of Catherine de' Medici (though this might refer to works by his ancestors, given the timeline, or perhaps early works), is a common fate for art over centuries. However, the substantial body of his work that survives in major collections allows for a thorough appreciation of his skill and artistic vision.

Conclusion: Dumonstier's Enduring Place in Art History

Daniel Dumonstier was a master of his chosen medium and a key figure in the lineage of French portraiture. Emerging from a distinguished artistic family, he absorbed the traditions of the French Renaissance crayon portrait and infused them with a new level of psychological depth and refined realism suited to the sensibilities of the early 17th century. His delicate yet incisive chalk portraits captured the likenesses of kings, queens, ministers, and nobles, offering an intimate glimpse into the French court at a formative period in its history.

Beyond his artistic achievements, Dumonstier was a man of his time: intellectually curious, engaged with the cultural and religious debates of his era, and a respected member of the courtly world. His imprisonment for his views adds a layer of complexity to his biography, reminding us that artists were often deeply embedded in the socio-political fabric of their society.

Today, Daniel Dumonstier is recognized as one of the last great practitioners of the independent crayon portrait before the medium was somewhat subsumed by oil painting's dominance or transformed into preparatory studies. His works remain a testament to his exceptional skill, his keen observational powers, and his ability to convey the subtle nuances of human character, securing his place as an important and distinctive voice in the history of French art.