Ottavio Leoni (1578–1630) stands as one of the most significant and prolific portraitists of early seventeenth-century Rome. An accomplished painter, a meticulous draughtsman, and a skilled printmaker, Leoni captured the likenesses of popes, cardinals, nobles, artists, and intellectuals, creating an invaluable visual record of Roman society during a vibrant period of artistic and cultural transformation. His ability to convey not just the physical features but also the psychological presence of his sitters has cemented his reputation as a pivotal figure in the development of Baroque portraiture.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Rome

Born in Rome in 1578, Ottavio Leoni was immersed in the world of art from a young age. His father, Ludovico Leoni (c. 1542–1612), was himself a respected artist, known primarily as a medallist, coin-engraver, and sculptor in wax. Ludovico, who also hailed from Padua and was thus sometimes referred to as "Il Padovano" (a moniker Ottavio would also inherit), provided his son with his initial artistic training. It is believed that Ludovico encouraged Ottavio to specialize in portraiture, particularly in the "alla macchia" style, a technique emphasizing speed and spontaneity to capture a fresh, lifelike impression of the sitter, often in a single session.

This paternal guidance was crucial in shaping Ottavio's artistic trajectory. Growing up in Rome, a city teeming with artistic innovation and intense competition, Leoni would have been exposed to a rich tapestry of influences. The legacy of High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo was still palpable, while new artistic currents were beginning to emerge, challenging established conventions. His father's connections within the artistic and potentially curial circles of Rome would have also provided Ottavio with an initial network and understanding of the patronage system that was vital for an artist's success.

The Roman Artistic Milieu in the Early Seicento

The Rome in which Ottavio Leoni matured as an artist was a dynamic and complex city. It was the center of the Catholic Church, and the papacy, particularly under Popes Clement VIII, Paul V, and later Urban VIII, was a major patron of the arts, using it to project power, piety, and magnificence. The Counter-Reformation was in full swing, influencing religious art, but secular subjects, especially portraiture, also flourished as a means for the elite to assert their status and preserve their legacy.

This era saw the revolutionary naturalism of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio shake the foundations of Roman painting. Simultaneously, the classicizing reforms of Annibale Carracci and his academy offered a different path, emphasizing drawing, study from life, and a more idealized beauty. Artists from across Italy and Europe flocked to Rome, including Peter Paul Rubens, Simon Vouet, and Adam Elsheimer, contributing to a fertile environment of exchange and rivalry. Leoni navigated this world, developing a distinct niche for himself. He became a member of the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's prestigious artists' guild, eventually serving as its Principe (President) in 1614, a testament to his esteemed position among his peers.

Leoni's Signature Portrait Style: "Alla Macchia" and Psychological Depth

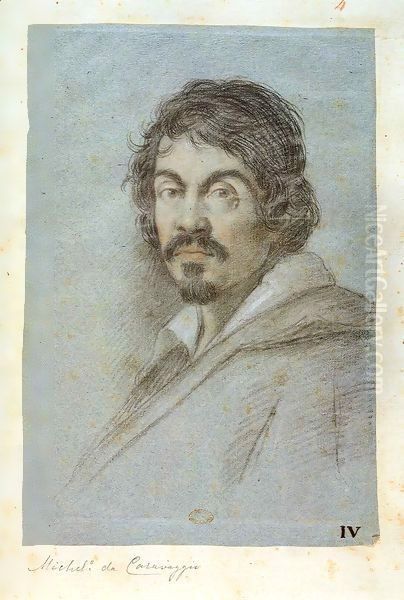

Ottavio Leoni is best known for his remarkable series of portrait drawings, typically executed in black, red, and white chalk (a technique known as aux trois crayons) on blue or toned paper. This medium allowed for both precision in capturing likeness and subtlety in modeling form and conveying texture. His preferred format was the bust-length or half-length portrait, focusing intently on the sitter's face and expression. The "alla macchia" approach, which his father advocated, was central to his practice. This involved drawing quickly from life, aiming to capture the essential character of the subject in a relatively short sitting.

The results were portraits of striking immediacy and psychological acuity. Leoni possessed an uncanny ability to render the subtle nuances of human expression, suggesting the sitter's personality, mood, and social standing. His subjects often gaze directly at the viewer, establishing a powerful connection. While adhering to conventions of decorum appropriate to the sitter's rank, Leoni's portraits rarely feel stiff or formulaic. Instead, they convey a sense of individuality and presence. He meticulously recorded details of costume and hairstyle, which not only add to the realism but also serve as important historical indicators of fashion and status. Many of these drawings bear inscriptions, often in Leoni's own hand, identifying the sitter and the date, further enhancing their documentary value.

Notable Sitters and Powerful Patrons

Leoni's clientele was extensive and diverse, reflecting his high standing in Roman society. He portrayed some of the most influential figures of his time. Popes, such as Paul V (Camillo Borghese), and cardinals, including Scipione Borghese, Maffeo Barberini (later Pope Urban VIII), and Ludovico Ludovisi, sat for him. These powerful churchmen were significant art patrons, and their commissions were crucial for any artist's career in Rome. Leoni's ability to secure their patronage speaks volumes about his skill and reputation.

Beyond the ecclesiastical hierarchy, Leoni depicted members of Rome's leading aristocratic families, such as the Borghese, Barberini, Colonna, Orsini, and Altemps. These families commissioned portraits to commemorate their lineage, celebrate important events like marriages, or simply to affirm their social prominence. His sitters also included prominent intellectuals, scientists, poets, and fellow artists. This breadth of clientele indicates that Leoni was not merely a court painter but an artist sought after by a wide spectrum of Rome's elite. His studio became a place where the "who's who" of Roman society convened to have their likenesses immortalized.

Representative Works: Capturing the Essence of an Era

While Leoni produced oil paintings, his drawings form the core of his celebrated oeuvre. Among his most famous works is the chalk portrait of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, dated around 1621 (though some scholars debate the date and even attribution, it is widely accepted). This drawing, now in the Biblioteca Marucelliana in Florence, is one of the few surviving contemporary likenesses of the notoriously volatile painter. Leoni captures Caravaggio's intense gaze and somewhat disheveled appearance, offering a glimpse into the personality of this revolutionary artist. The directness and lack of idealization are characteristic of Leoni's approach.

Another significant work is the Portrait of Galileo Galilei, which showcases Leoni's ability to portray men of science and intellect with dignity and insight. His series of portraits of artists, including Giovanni Baglione (a contemporary artist and biographer, and a rival of Caravaggio), Simon Vouet, and potentially a young Gian Lorenzo Bernini, are invaluable for art historians. These portraits often convey a sense of camaraderie or professional respect.

Leoni also created painted portraits, sometimes based on his drawings. An example is the Portrait of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a powerful patron of the arts. While his paintings might not always possess the same startling immediacy as his chalk drawings, they demonstrate his competence in the oil medium and his ability to adapt his style to the more formal demands of painted portraiture. He also produced some religious paintings and altarpieces, though these are less central to his fame than his portraits. The Procession of a Cardinal (1621) is an interesting example of a more complex composition, though its specific subject and symbolism remain somewhat debated among scholars.

Leoni as a Printmaker: Disseminating Images

Beyond his drawings and paintings, Ottavio Leoni was a highly accomplished printmaker, working primarily in etching and engraving. He produced a series of engraved portraits, often based on his own drawings, which were then disseminated more widely. This practice allowed his work to reach a broader audience and contributed to the growing market for portrait prints in the 17th century. These prints, like his drawings, are characterized by their fine detail and sensitive rendering of character.

His series of engraved portraits of artists, writers, and other notables, published from around 1621 onwards, formed a kind of visual pantheon of contemporary Roman figures. These prints were sometimes used as book illustrations or collected by connoisseurs. The technical skill evident in his engravings, with their delicate lines and subtle tonal gradations, places him among the accomplished printmakers of his era. This aspect of his work underscores his versatility and his engagement with different artistic media to achieve his aims. Artists like Claude Mellan, who later became a renowned portrait engraver in Paris, would have been aware of Leoni's contributions in this field.

Relationships, Influences, and Artistic Circle

Ottavio Leoni's artistic development was shaped by his father, Ludovico, and the broader Roman art scene. While he was not a direct pupil of any single major master other than his father, he absorbed influences from various sources. The Venetian tradition of portraiture, exemplified by Titian and Tintoretto, with its emphasis on color, texture, and psychological depth, likely informed his approach to painted portraits. The naturalism of Caravaggio was an undeniable force in Rome, and while Leoni's style was generally more restrained and less overtly dramatic, the commitment to depicting subjects with unvarnished realism can be seen as a shared concern.

Leoni was certainly acquainted with Caravaggio. Beyond portraying him, Leoni was peripherally involved in the infamous 1603 libel trial initiated by Giovanni Baglione against Caravaggio, Orazio Gentileschi, Onorio Longhi, and Filippo Trisegni. Leoni's testimony in such legal matters, or his mere presence in these circles, indicates his integration within the often-turbulent artistic community of Rome.

He also maintained connections with other prominent artists. He portrayed the Flemish master Anthony van Dyck during the latter's Italian sojourn, a testament to the mutual respect among leading portraitists. His association with the Accademia di San Luca brought him into contact with figures like Federico Zuccari, an older, established master, and younger contemporaries. The "aux-trois-crayons" technique he favored had precedents in French art (e.g., François Clouet) and was also practiced by some Italian artists, but Leoni made it distinctively his own. There's speculation that he might have been influenced by the Spanish theorist and painter Francisco Pacheco regarding certain drawing techniques, though this is less definitively established. His circle would have also included artists like Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) and the young Bernini, both of whom were rising stars in Rome.

Artistic Controversies and Scholarly Debates

Despite the clarity of many of his inscriptions, some aspects of Leoni's work remain subjects of scholarly discussion. Attribution can occasionally be a challenge, particularly with oil paintings that lack the distinctiveness of his chalk drawings. The precise dating of some works is also debated. For instance, the famous Caravaggio portrait's date has been discussed, with some suggesting it might be earlier than the commonly cited c. 1621, or even posthumous, though the latter is less widely accepted.

The interpretation of certain works, like the aforementioned Procession of a Cardinal, presents iconographic puzzles. The identities of some sitters in his less-documented portraits remain anonymous, leaving art historians to speculate based on costume, bearing, or resemblance to other known figures. The question of workshop participation is also relevant for a successful artist like Leoni; while his drawings often feel intensely personal, the extent to which assistants might have been involved in preparatory work or replicas of paintings is a standard art historical inquiry.

Furthermore, the consistency of his style versus its diversity has been noted. While his chalk portraits have a recognizable character, his painted works can vary. This might reflect his adaptation to different patronal demands, the influence of other artists, or simply the evolution of his own practice over several decades. These are not so much "controversies" in a dramatic sense but rather the ongoing scholarly investigations that enrich our understanding of any major artist's oeuvre.

Later Career, Legacy, and Enduring Impact

Ottavio Leoni remained active and highly regarded throughout his career until his death in Rome in September 1630. He was buried in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo, in the Leoni family chapel, a prestigious resting place. His extensive series of portrait drawings, many of which were kept together for a considerable time after his death, eventually found their way into important collections, notably the Biblioteca Marucelliana in Florence and the Fondazione Cini in Venice, as well as numerous other museums worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

His legacy is multifaceted. Firstly, he provided an unparalleled visual chronicle of Roman society in the early Baroque period. His portraits offer intimate glimpses of the individuals who shaped the political, religious, and cultural life of the city. Secondly, his mastery of chalk drawing, particularly his ability to capture character with economy and precision, set a high standard for portrait draughtsmanship. He influenced subsequent generations of portraitists, both in Italy and beyond. Artists like Carlo Maratta in the later Baroque period continued the tradition of refined portrait drawing.

Thirdly, his work as a printmaker contributed to the popularization of portraiture and the dissemination of images of notable individuals. He demonstrated how printmaking could be a powerful tool for an artist to extend their reach and reputation. His commitment to realism, combined with a subtle psychological insight, aligned with the broader Baroque interest in human emotion and individuality. While perhaps not as revolutionary as Caravaggio or as monumental as Bernini, Ottavio Leoni carved out a unique and enduring place in the history of art through his dedicated and insightful portrayal of the human face.

Conclusion: A Chronicler of an Age

Ottavio Leoni was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was a sensitive observer of humanity. In an age of grand religious narratives and dramatic historical paintings, Leoni focused his considerable talents on the individual. His portraits, whether in chalk, oil, or print, transcend mere likeness to offer profound insights into the character and spirit of his sitters. He captured the confidence of the powerful, the intellect of the scholar, the intensity of the fellow artist, and the quiet dignity of many others.

His work serves as a vital bridge between the more formal portraiture of the late Renaissance and the increasingly dynamic and psychologically charged portraits of the High Baroque. As an artist who was highly respected in his own time, a leader in the Accademia di San Luca, and a chronicler of popes, princes, and poets, Ottavio Leoni's contribution to art history is undeniable. His drawings, in particular, remain a source of fascination and admiration, offering a direct and intimate connection to the people who inhabited Rome during one of its most artistically fertile periods. His dedication to the art of portraiture has left us with a rich and enduring gallery of faces from a bygone era, each telling its own silent story.