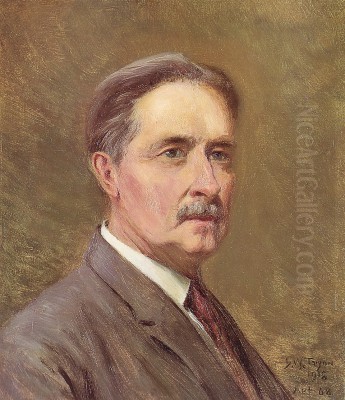

Dwight William Tryon stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly renowned for his contributions to the Tonalist movement that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His evocative landscapes, characterized by their subtle gradations of color, atmospheric depth, and poetic sensibility, captured the quiet beauty of the New England countryside and coastal scenes. Tryon's journey from a self-taught enthusiast to an influential artist and educator reflects a deep commitment to his craft and a unique artistic vision that left an indelible mark on American landscape painting.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Hartford

Dwight William Tryon was born on August 13, 1849, in Hartford, Connecticut. His early life was marked by hardship; his father, Anson Tryon, tragically died in a shooting accident when Dwight was merely two years old. Consequently, the young Tryon was raised by his mother and grandmother. This early loss and the responsibilities it entailed likely shaped his character, instilling in him a sense of diligence and perseverance.

To support his family, Tryon began working at a young age. By fourteen, he was employed at Colt's Firearms factory in Hartford, a prominent industrial enterprise of the era. Concurrently, he sought to improve his prospects by attending night classes at Hannum's Business School. These early experiences in the industrial and commercial world of Hartford provided a stark contrast to the artistic path he would eventually pursue.

Despite the lack of formal artistic training in his youth, Tryon developed a profound interest in drawing and painting. He was largely self-taught in his initial artistic endeavors, honing his skills through observation and practice. His passion for art grew steadily, and he began to envision a future where he could dedicate himself entirely to his creative pursuits. This burgeoning ambition was a testament to his innate talent and his determination to transcend the conventional career paths available to him.

The Decision for Art and Early Ventures

The allure of art proved irresistible for Tryon. By the age of 21, around 1870, he made a pivotal decision that would define the course of his life: he resolved to become a professional artist. This was a bold step, particularly for someone without formal academic art training at that point. He began by selling his paintings locally, and his early subjects often included landscapes and marine scenes, reflecting the natural beauty of the New England environment that surrounded him.

His entrepreneurial spirit, perhaps honed by his business school education, served him well. He initially worked in a bookstore, a position that likely provided him with access to art books and reproductions, further fueling his artistic education. He sold his first painting around this time, an encouraging sign that his work resonated with buyers. The proceeds from these early sales were crucial, as he used them to fund his ongoing self-education and, eventually, his more formal artistic studies.

In 1873, Tryon's work gained its first significant public exposure when he exhibited at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York. This was a notable achievement for a young, largely self-taught artist. He received further recognition from the Academy in 1874, which helped to solidify his reputation and encourage him to pursue more advanced training. These early successes were vital in confirming his artistic calling and providing the impetus for the next major phase of his development.

Formative Years in Europe: The Barbizon Influence

Recognizing the need for formal instruction and exposure to the great art traditions, Tryon, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, looked towards Europe. In 1876, he embarked on a journey to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. This was a period of intense artistic ferment in Paris, with Impressionism, championed by artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, challenging the established academic norms.

However, Tryon was not primarily drawn to the radical newness of Impressionism. Instead, he found a deeper connection with the artists of the Barbizon School. He enrolled in the atelier of Jacques-Édouard de la Chevreuse (often cited as Jacques de la Chevrance) and also received guidance from prominent figures associated with or influenced by the Barbizon tradition, including Charles-François Daubigny and Henri Jules Harpignies. He also studied with Antoine Guillemet. The Barbizon painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean-François Millet, were known for their intimate and lyrical depictions of rural landscapes, emphasizing mood, atmosphere, and the subtle effects of light.

Daubigny, in particular, was a significant influence with his gentle, poetic river scenes and his practice of painting directly from nature, often from a studio boat. Harpignies, known for his structured yet atmospheric landscapes, also imparted valuable lessons. Tryon absorbed their emphasis on capturing the emotional essence of a scene rather than a purely topographical rendering. He diligently studied their techniques, focusing on tonal harmony, a limited but expressive palette, and the creation of a unified, poetic mood.

During his time in Europe, which lasted until 1881, Tryon also traveled beyond France. He visited Holland, where he would have encountered the works of the Dutch Golden Age landscape painters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, whose atmospheric qualities prefigured some Barbizon concerns. He also journeyed to Italy and the Channel Islands , sketching and absorbing diverse landscapes. This period of study and travel was crucial in refining his technique and solidifying his artistic philosophy, steering him firmly towards the Tonalist aesthetic that would define his mature work.

Return to America: Establishing a Career and a Voice

In 1881, Dwight William Tryon returned to the United States, his artistic vision sharpened and his technical skills considerably advanced. He chose New York City as his base, opening a studio and immersing himself in the burgeoning American art scene. New York was rapidly becoming a major cultural center, and Tryon found a receptive environment for his work.

His European training, particularly his association with the Barbizon School, resonated with a growing American taste for more intimate and poetic landscapes, a departure from the grand, panoramic vistas of the earlier Hudson River School artists like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church. Tryon's paintings, with their subtle color harmonies and evocative moods, found favor with collectors and critics.

A significant turning point in his career came in 1885 when he was appointed Professor of Art at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. This marked the beginning of a long and distinguished academic career that would span nearly four decades. At Smith, he was not just a teacher but a formative influence on the institution's art program. He eventually became the head of the art department, a position he held until his retirement in 1923. His role at Smith College allowed him to shape the artistic education of generations of students and to advocate for the importance of art within a liberal arts curriculum.

Alongside his teaching responsibilities, Tryon continued to paint prolifically. He maintained his studio in New York but also spent considerable time in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, where he found inspiration in the coastal landscapes and rural scenery. His summers were often spent there, allowing him to immerse himself in the environments that he so sensitively depicted in his work.

The Essence of Tonalism: Tryon's Artistic Vision

Dwight William Tryon is best known as a leading exponent of American Tonalism. Tonalism, which flourished from roughly the 1880s to the 1910s, was less a formal school and more an artistic sensibility. It emphasized mood, atmosphere, and spirituality over detailed representation. Tonalist painters favored soft edges, muted palettes often dominated by grays, browns, blues, and greens, and simplified forms to evoke a sense of quiet contemplation and harmony with nature. Artists like George Inness, James McNeill Whistler, Thomas Wilmer Dewing (a close friend of Tryon), Ralph Albert Blakelock, and Alexander Helwig Wyant are also closely associated with this movement.

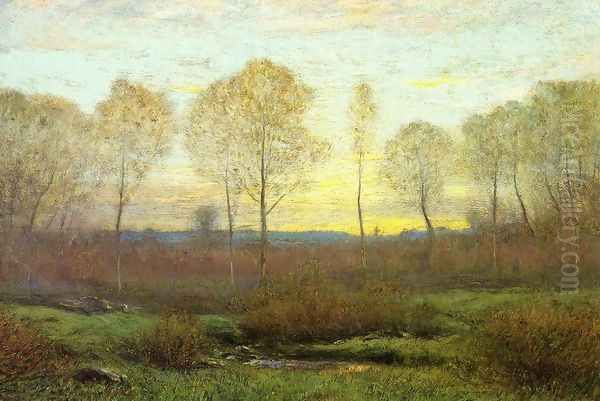

Tryon's Tonalism was deeply rooted in the Barbizon aesthetic he had absorbed in France. Like Corot and Daubigny, he sought to capture the subjective experience of nature, the feeling a landscape evoked, rather than its literal appearance. His paintings are often characterized by a soft, diffused light, typically depicting dawn, dusk, or overcast days, times when the light is gentle and forms are veiled in atmosphere. This creates a sense of intimacy and introspection.

A distinctive aspect of Tryon's approach was his preference for painting from memory. While he sketched outdoors, his finished canvases were typically created in the studio. This allowed him to distill the essential qualities of a scene, filtering it through his artistic sensibility to achieve an idealized and poetic interpretation. His landscapes are not specific locations meticulously recorded, but rather composite visions that convey a universal sense of peace and tranquility.

There is also evidence of Japanese art's influence on Tryon's work, a common thread among many Tonalist and Aesthetic Movement artists of the period, including Whistler and Dewing. This influence can be seen in his subtle color harmonies, his attention to delicate surface textures, and sometimes in his compositional arrangements, which could emphasize asymmetry and flattened space. The refined aesthetics of Japanese prints and paintings resonated with the Tonalist pursuit of beauty and suggestion.

Masterworks and Signature Style

Several paintings exemplify Dwight William Tryon's mature Tonalist style. Among his most celebrated works are Salt Marsh, December and The Sea: Evening. These titles themselves suggest the temporal and atmospheric qualities that were central to his art.

Salt Marsh, December (c. 1890s-1900s) likely depicts a coastal New England scene in the muted light of a winter's day. One can imagine the subtle browns, grays, and ochres of dormant marsh grasses under a soft, overcast sky. Tryon excelled at capturing the quiet desolation and subtle beauty of such scenes, finding poetry in the seemingly mundane. The emphasis would be on the horizontal expanse of the marsh, the delicate tracery of grasses, and the overall harmony of cool, subdued tones.

The Sea: Evening (various dates for sea pieces) would similarly focus on atmosphere and light. Evening seascapes allowed Tryon to explore the transition from day to night, the play of fading light on water, and the merging of sea and sky into a unified tonal field. These works often evoke a sense of calm, mystery, and the sublime power of nature experienced in a quiet, contemplative mode. The horizon line is often low, emphasizing the vastness of the sky, and the color palette would be restricted to capture the crepuscular light.

Other characteristic subjects included moonlit nights, misty mornings, and the changing seasons in the New England landscape. He often painted series of works depicting different times of day or year, allowing him to explore the nuanced effects of light and atmosphere on a familiar motif. His paintings of apple orchards in bloom or fields of grain under soft skies are imbued with a gentle lyricism. The human presence is usually absent or minimal in his landscapes, enhancing the sense of solitude and communion with nature.

His technique involved building up layers of thin glazes of paint to achieve luminous depth and subtle tonal transitions. His brushwork was often delicate and controlled, contributing to the refined and polished surface of his canvases. The overall effect is one of quiet elegance and profound emotional resonance.

A Respected Educator and Patronage

Tryon's nearly forty-year tenure at Smith College was highly influential. As a professor and later as the head of the art department, he played a crucial role in developing the college's art curriculum and its art collection. He believed in the importance of exposing students to original works of art and was instrumental in acquiring pieces for the college.

His teaching philosophy likely emphasized the principles he himself valued: keen observation, an understanding of tonal harmony, and the pursuit of poetic expression. He would have encouraged his students to look beyond mere imitation of nature and to develop their own artistic voice. His dedication to art education contributed significantly to the cultural enrichment of Smith College and its students.

One of Tryon's most important relationships was with the prominent art collector Charles Lang Freer. Freer, whose collection would form the basis of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (part of the Smithsonian Institution), was a major patron of American Tonalist painters, most notably James McNeill Whistler and Thomas Dewing. Freer also had a deep appreciation for Asian art, and he saw connections between the aesthetic principles of Eastern art and the work of artists like Tryon.

Freer acquired numerous paintings by Tryon, recognizing the refined beauty and spiritual depth of his landscapes. This patronage was not only financially important for Tryon but also provided him with a significant endorsement from one of the leading connoisseurs of the era. The inclusion of Tryon's work in Freer's collection, alongside masterpieces of Asian art and works by Whistler, placed him in an esteemed international context. The Freer Gallery of Art today holds a significant collection of Tryon's paintings, offering a testament to this important artist-patron relationship.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Dwight William Tryon worked during a dynamic period in American art. The late 19th century saw the decline of the Hudson River School's dominance and the rise of new artistic currents, many of them influenced by European developments. Tonalism emerged as a distinctly American response, blending Barbizon influences with a native sensibility and often a touch of Transcendentalist philosophy.

Tryon was a contemporary of other leading Tonalists. George Inness, an older figure, was a pioneer of the style, moving from a detailed Hudson River School approach to increasingly subjective and spiritual landscapes. James McNeill Whistler, though often associated with the Aesthetic Movement, was a key figure whose "Nocturnes" and subtle color harmonies profoundly influenced Tonalism. Thomas Wilmer Dewing, a close friend of Tryon, specialized in ethereal figure paintings set in misty, Tonalist landscapes, often collaborating with Stanford White on frame designs, as did Tryon.

Other notable Tonalists included Ralph Albert Blakelock, known for his richly impastoed, moonlit scenes, and Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose visionary and deeply personal paintings share Tonalism's emphasis on mood and imagination. J. Francis Murphy was another contemporary landscape painter whose work often shared the soft, poetic qualities of Tonalism.

While Tonalism was gaining prominence, American Impressionism was also taking root, with artists like Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and J. Alden Weir adapting French Impressionist techniques to American subjects. Twachtman, in particular, created works that sometimes bordered on Tonalism with their delicate palettes and atmospheric effects. Tryon's commitment to the more subdued, introspective qualities of Tonalism set his work apart from the brighter palette and broken brushwork of the Impressionists.

His career also spanned the rise of early modernism in America, with events like the Armory Show of 1913 introducing avant-garde European art to a wider American audience. While Tryon remained true to his Tonalist vision, the art world around him was undergoing rapid transformation. Artists like Marsden Hartley and John Marin were exploring new modes of expression that challenged traditional landscape painting.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Dwight William Tryon continued to paint and teach into the early 20th century. He maintained his studio in New York City, often working in the Harperley Hall apartments, and spent his summers and creative retreats in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, at his property in Padanaram. This coastal environment provided endless inspiration for his serene marine and landscape paintings.

His dedication to his art and his students remained steadfast. However, by the early 1920s, his health began to decline. In 1923, he retired from his long and distinguished service at Smith College. The following year, in 1924, his health issues forced him to stop painting altogether.

In recognition of his immense contributions to the college and to American art, Smith College established the Tryon Gallery of Art in 1924 (now the Smith College Museum of Art, which still features the Tryon Gallery). This was a fitting tribute, ensuring that his work and the art he helped acquire would continue to inspire future generations.

Dwight William Tryon passed away on July 1, 1925, in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts. He bequeathed a significant number of his paintings and his personal collection of art, which included works by his contemporaries and Japanese prints, to Smith College. This generous gift further enriched the college's museum and solidified his lasting legacy there.

Today, Tryon's paintings are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Freer Gallery of Art, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Detroit Institute of Arts, and, of course, the Smith College Museum of Art. His work continues to be appreciated for its quiet beauty, its technical mastery, and its profound connection to the American landscape.

Conclusion: The Quiet Poetry of Dwight William Tryon

Dwight William Tryon's art offers a tranquil refuge, a world of subtle beauty and contemplative calm. As a leading figure of American Tonalism, he masterfully captured the elusive moods and atmospheric effects of the New England landscape. His journey from a self-taught artist in Hartford to a revered painter and influential educator is a story of dedication and a singular artistic vision.

Influenced by the Barbizon School and the refined aesthetics of Japanese art, Tryon developed a distinctive style characterized by harmonious color, soft light, and an emphasis on poetic suggestion rather than literal depiction. His landscapes, often painted from memory, are not merely records of places but evocations of feeling, inviting viewers into a world of serene introspection. Through his long career as an artist and as a professor at Smith College, and through the enduring patronage of collectors like Charles Lang Freer, Tryon made a lasting contribution to American art. His paintings remain a testament to the enduring power of nature to inspire and to the artist's ability to translate that inspiration into works of quiet, enduring poetry.