John Francis Murphy, born in 1853 and passing away in 1921, stands as a significant figure in the landscape of American art history. An American national, he rose from humble beginnings to become one of the most respected landscape painters of his era, particularly associated with the Tonalist movement. His career, marked by a dedication to self-education and a profound sensitivity to the nuances of nature, offers a compelling narrative of artistic development within the context of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century American painting. Murphy's work is celebrated for its poetic interpretation of the natural world, rendered with subtle color harmonies and a masterful handling of light and atmosphere.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Francis Murphy's journey into the art world began not in formal academies, but through keen observation and persistent practice. Born in Oswego, New York, his early life provided little indication of his future artistic prominence. At the age of fifteen, his family relocated to Chicago, a burgeoning city that would serve as the initial backdrop for his artistic endeavors. It was here that Murphy first engaged in commercial art, undertaking practical work painting advertising billboards and theatrical scenery. This early experience, though not fine art in the traditional sense, likely honed his skills in handling paint and understanding visual composition on a large scale.

Despite lacking formal art instruction, Murphy possessed an innate drive to capture the world around him. He was, in essence, entirely self-taught, learning his craft through diligent study of nature and the works of other artists he admired. This path of self-reliance shaped his individualistic approach and perhaps contributed to the unique sensitivity found in his later landscapes. His time in Chicago was formative, providing practical skills and likely exposing him to the developing art scene of the Midwest.

The year 1874 marked a pivotal moment. Murphy reportedly sold his artistic creations to finance an extended sketching trip to the scenic Adirondack Mountains in New York State. This immersion in the wilderness provided him with invaluable firsthand experience of the landscapes that would become central to his art. A year later, in 1875, seeking greater opportunities and immersion in the nation's primary art center, Murphy moved to New York City. He initially worked as an illustrator but soon established his own studio, signaling his full commitment to pursuing a career as a professional landscape painter.

The Emergence of a Tonalist Vision

Settling in New York, Murphy began to refine his artistic voice, increasingly aligning himself with the burgeoning Tonalist movement. Tonalism, which flourished in America roughly between 1880 and 1915, was less a formal school and more an aesthetic sensibility. It diverged from the detailed realism of the Hudson River School and the bright palettes of Impressionism, favoring instead intimate, evocative landscapes characterized by muted colors, soft edges, and a profound sense of mood and atmosphere. Tonalist painters sought to capture the subjective feeling of a place, often depicting scenes at twilight, dawn, or in hazy, misty conditions.

Murphy's style perfectly encapsulated these ideals. His work demonstrated a deep appreciation for the subtle beauties of the American landscape, often focusing on quiet, unassuming scenes rather than dramatic vistas. He was profoundly influenced by the French Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, whose poetic, atmospheric landscapes resonated with Murphy's own inclinations. Like Corot, Murphy excelled at simplifying forms and using a limited palette to achieve tonal harmony and emotional depth. His sensitive rendering of light and air led some contemporaries to refer to him as the "American Corot," a testament to his mastery of mood.

His paintings often feature delicate transitions between colors, creating a unified, harmonious effect. He masterfully captured the specific qualities of light during different times of day and seasons, particularly favoring the soft, diffused light of early morning, late afternoon, or overcast days. His brushwork, while controlled, often possessed a softness that contributed to the dreamlike, poetic quality of his work. Murphy wasn't merely recording nature; he was interpreting it, imbuing his landscapes with a sense of quiet contemplation, intimacy, and sometimes a gentle melancholy. His focus was on the "mist, shadow, and mystery" inherent in the natural world.

Influences and Artistic Circle

No artist develops in a vacuum, and John Francis Murphy was deeply connected to the artistic currents of his time, drawing inspiration from predecessors and engaging with contemporaries. His affinity for the French Barbizon painters, particularly Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jean-François Millet, is well-documented and evident in his stylistic choices – the emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and the poetic potential of humble rural scenes.

Within the American context, Murphy looked closely at the work of slightly older landscape painters who were also bridging the gap between the Hudson River School and more subjective approaches. George Inness, a towering figure in American landscape painting often associated with both the Barbizon influence and Tonalism, was particularly significant. Murphy admired Inness's spiritual and emotive approach to nature and learned much from his handling of light and color to evoke deep feeling. Alexander Helwig Wyant, another key figure whose later work embraced Tonalist sensibilities, was also an important influence, known for his subtle, intimate portrayals of the American landscape. Homer Dodge Martin, whose work evolved towards a more simplified, abstract, and moody style, also provided inspiration.

Murphy was part of a generation of American artists exploring similar aesthetic territory. He shared the Tonalist sensibility with contemporaries like Dwight William Tryon, known for his delicate, atmospheric landscapes, and Thomas Wilmer Dewing, who applied Tonalist principles primarily to figure painting but shared the emphasis on refined aesthetics and mood. Ralph Albert Blakelock, though possessing a highly individualistic and sometimes darker vision, also worked within a related vein, creating deeply textured and evocative landscapes.

Beyond direct stylistic influence, Murphy formed connections within the art community. During his early years, possibly in Chicago or later in New York, he established friendships with fellow artists such as Emil Carlsen, a Danish-American painter known for both still lifes and landscapes, often imbued with a Tonalist quietude, and Theodore Robinson, who, although primarily known as an American Impressionist, shared friendships within broader artistic circles. While Murphy's primary focus remained landscape, his career unfolded alongside major figures working in different styles, such as the great realist and marine painter Winslow Homer and the visionary symbolist Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose unique works also emphasized mood over literal description. He would also have been aware of the rising tide of American Impressionism, championed by artists like Childe Hassam and J. Alden Weir, even as he remained committed to his Tonalist path. These interactions, whether through direct influence, friendship, or simply shared exhibition spaces, placed Murphy firmly within the rich tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century American art.

Representative Works and Dominant Themes

John Francis Murphy's oeuvre is characterized by a consistent dedication to capturing the quiet poetry of the American landscape. While his subject matter might seem limited primarily to pastoral scenes, his strength lay in the infinite variations of mood, light, and atmosphere he could evoke from these familiar settings. His works often depict transitional moments in nature – the lingering light of autumn, the quiet blanket of winter snow, the hazy atmosphere of late summer, or the soft glow of twilight.

Among his notable works, Late Autumn (1897) exemplifies his mature Tonalist style. Such paintings typically feature sparse compositions, perhaps a few skeletal trees against a muted sky, rendered in a harmonious palette of browns, grays, and golds. The emphasis is not on topographical accuracy but on the melancholic beauty and quietude of the season's end. The subtle gradations of tone and soft brushwork create an enveloping atmosphere, inviting contemplation.

Clearing Snow (1912), likely depicting a winter scene after a snowfall, would showcase Murphy's ability to handle the challenging nuances of white and gray. Tonalist painters often found winter landscapes appealing for their inherent simplicity and opportunities to explore subtle value shifts. Murphy would have focused on the soft light on the snow, the delicate tracery of bare branches, and the overall hushed feeling of the landscape under its winter mantle.

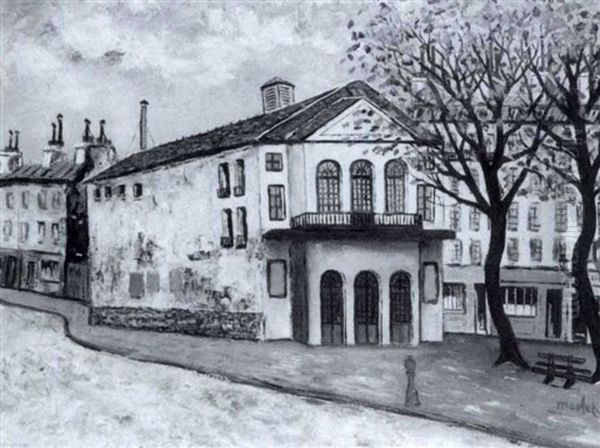

Works like Old Sawmill, Arkville point to his connection to specific locales. Arkville, located in the Catskill Mountains, was an area frequented by artists, including Murphy himself, who established a home and studio there later in his life, named "Arkville." This painting likely captures a rustic structure within its natural setting, imbued with the characteristic atmospheric haze and poetic sentiment that define his work. The sawmill itself would be secondary to the overall mood and the interplay of light and shadow on the building and surrounding landscape.

The Pond is another title suggestive of his typical subject matter. Ponds, streams, and marshes were frequent motifs for Tonalist painters, offering reflective surfaces that allowed for complex plays of light and subtle color harmonies. Murphy would likely have depicted such a scene with soft edges, perhaps shrouded in mist or bathed in the gentle light of dawn or dusk, emphasizing tranquility and the quiet mysteries of nature.

Throughout his career, Murphy repeatedly returned to these themes, exploring the landscape of the Northeast, particularly New York and New England. His works consistently avoid grandiosity, focusing instead on the intimate and the lyrical. He sought the universal truths embedded in simple scenes, rendered with a technical finesse and emotional resonance that secured his reputation.

Career Recognition and Achievements

John Francis Murphy's dedication and unique artistic vision did not go unnoticed by the art establishment of his time. His career was marked by consistent exhibition activity and the reception of numerous prestigious awards, affirming his position within the American art world. His relationship with the National Academy of Design (NAD) in New York was particularly significant. He first exhibited there in 1876, a crucial early step for an aspiring artist. His talent was recognized relatively quickly; he was elected an Associate member (ANA) in 1885 and achieved the status of full Academician (NA) just two years later, in 1887. Membership in the NAD was a major indicator of professional success and peer recognition.

His success at the NAD was further solidified by winning the Second Hallgarten Prize in 1885, an award given to promising young artists. In 1887, the same year he became a full Academician, his painting Tints of a Vanished Past won the prestigious Thomas B. Clarke Prize for figure composition (though primarily a landscape painter, this suggests the work may have included figures or the prize criteria were broader). More central to his landscape focus, he later received the coveted Inness Gold Medal from the NAD in 1910, an award named after the artist who had so profoundly influenced him.

Murphy also gained recognition from other important arts organizations. He was awarded the Webb Prize by the Society of American Artists (SAA) in 1887 and the Carnegie Prize from the same organization in 1902. He received the Evans Prize from the American Watercolor Society in 1894, indicating his proficiency in that medium as well. His work was selected for inclusion in major national and international expositions, where he also garnered accolades. He won a silver medal at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901 and a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. These awards not only brought prestige but also increased the visibility and marketability of his work.

Beyond awards, Murphy was an active member of the artistic community, holding memberships in organizations such as the Society of American Artists, the American Watercolor Society, and the Salmagundi Club, a prominent New York City art club. This consistent recognition through exhibitions, awards, and memberships underscores the high regard in which John Francis Murphy was held by critics, collectors, and fellow artists during his lifetime.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

In his later years, John Francis Murphy continued to paint prolifically, often working from his studio in Arkville, New York, nestled in the Catskill Mountains. This region, long beloved by American landscape painters, provided endless inspiration. His style remained largely consistent, dedicated to the Tonalist principles he had mastered, though some critics note subtle shifts or refinements over time. He maintained his reputation as a leading landscape painter, and his works continued to be sought after by collectors and museums.

His dedication to his craft remained unwavering until the end of his life. John Francis Murphy passed away from pneumonia in New York City in 1921, at the age of 68. His death was noted with sadness in the art press, with publications like the American Art News acknowledging the loss of a significant figure in American art.

In the decades following his death, Murphy's reputation, like that of many Tonalist painters, experienced a period of relative obscurity as modernist movements came to dominate the art world. However, renewed scholarly and curatorial interest in American Tonalism from the mid-20th century onwards has led to a reappraisal of his contributions. Today, John Francis Murphy is recognized as a key exponent of the Tonalist movement and an important figure in the broader history of American landscape painting.

His legacy rests on his ability to convey deep emotion and poetic feeling through subtle means. As a self-taught artist who achieved significant recognition, his career is also a testament to individual talent and perseverance. His paintings offer a quiet, introspective counterpoint to the more dramatic or objective styles of his contemporaries. They invite viewers to pause and appreciate the nuanced beauty of the natural world, rendered through a masterful control of tone, light, and atmosphere. His works are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, and many others, ensuring that his unique vision continues to be accessible to future generations.

Conclusion: An Enduring Poetic Voice

John Francis Murphy carved a distinct and enduring niche within American art history. Rising from a background devoid of formal artistic training, he cultivated a deeply personal and resonant style that placed him at the forefront of the Tonalist movement. His landscapes are not mere transcriptions of scenery but are imbued with mood, atmosphere, and a profound sense of poetry. Influenced by the French Barbizon tradition and American precursors like George Inness and Alexander Wyant, Murphy developed a signature approach characterized by harmonious, muted palettes, soft edges, and an exquisite sensitivity to the effects of light.

His consistent exhibition record, numerous awards, and election to the National Academy of Design attest to the high esteem in which he was held during his lifetime. While his focus on intimate, pastoral scenes might seem narrow to some, his ability to extract infinite variations of mood and feeling from these subjects reveals his depth as an artist. Works like Late Autumn and Clearing Snow continue to captivate viewers with their quiet beauty and technical mastery.

Though overshadowed for a time by subsequent art movements, John Francis Murphy's reputation has been firmly re-established. He is celebrated for his contribution to American Tonalism and for his unique ability to translate the subtle, often overlooked aspects of the natural world into paintings of enduring lyrical power. His work remains a testament to the expressive potential of landscape painting and secures his place as a significant and sensitive voice in the chorus of American art.