Edoardo Dalbono stands as a significant figure in the vibrant tapestry of 19th and early 20th-century Italian art. An accomplished painter hailing from Naples, his life (1841-1915) spanned a period of profound artistic transformation in Italy. Dalbono carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming renowned primarily for his evocative landscapes, particularly those capturing the unique light and atmosphere of his native region, alongside compelling historical and mythological scenes often steeped in local folklore. His work represents a fascinating blend of observational realism and poetic sensibility, securing his place as a key interpreter of the Neapolitan artistic spirit.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Naples

Born in Naples in 1841, Edoardo Dalbono entered a city pulsating with artistic energy and cultural heritage. His father, Carlo Tito Dalbono, was a respected literary scholar and art critic, suggesting an environment where culture and the arts were valued. This familial background likely provided early exposure and encouragement for the young Edoardo's artistic inclinations. His formal training began not in Naples, but in Rome, where he studied under the sculptor Augusto Marchetti. This initial grounding in three-dimensional form may have subtly influenced his later understanding of structure and volume in painting.

However, Naples, the undisputed center of Southern Italian art, soon called him back. He enrolled at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli (Naples Academy of Fine Arts), an institution that had nurtured generations of artists. Here, he came under the tutelage of influential figures who would shape his development. Giuseppe Mancinelli, known for his historical and portrait painting, provided a foundation in academic tradition.

Perhaps more significantly, Dalbono studied under Domenico Morelli, a towering figure in Neapolitan painting. Morelli was a leading force in moving Italian art away from staid Neoclassicism towards a more realistic, yet often dramatically charged, style, frequently exploring historical, religious, and literary themes with a rich palette and vigorous brushwork. Morelli's emphasis on emotional depth and painterly technique undoubtedly left a lasting impression on Dalbono. The source material also suggests an association or period of study with Nicola Palizzi, another important Neapolitan painter known for his realistic landscapes and animal studies, further grounding Dalbono in the observation of nature.

The Neapolitan Artistic Milieu: Posillipo and Realism

Dalbono's formative years unfolded against the backdrop of competing but overlapping artistic currents in Naples. The legacy of the Scuola di Posillipo (Posillipo School) was still palpable. Founded earlier in the century by the Dutch painter Anton Sminck van Pitloo and championed by artists like Giacinto Gigante, this school specialized in small-scale, atmospheric landscape paintings, often executed outdoors (en plein air). They focused on capturing the picturesque beauty, luminous light, and transient effects of weather around the Bay of Naples. Their work was characterized by freshness, immediacy, and a departure from purely topographical representation towards a more personal, lyrical interpretation of nature.

Simultaneously, the push towards Verismo (Realism) was gaining momentum, spearheaded by figures like Domenico Morelli and the Palizzi brothers (Filippo and the aforementioned Nicola). This movement emphasized truthfulness to nature and contemporary life, often employing a more robust technique and a broader range of subjects than the often idyllic Posillipo views. Dalbono absorbed elements from both traditions. He inherited the Posillipo School's sensitivity to light and atmosphere and its deep connection to the Neapolitan landscape, but combined it with the stronger forms, richer color, and sometimes broader thematic scope associated with Morelli and the Realists.

The Resina School Connection

Further enriching Dalbono's engagement with landscape realism was his association with the Scuola di Resina (Resina School), sometimes referred to as the Republic of Portici. This informal group of artists gathered in the vicinity of Resina (modern Ercolano, near Herculaneum) during the 1860s. They were united by a desire to paint directly from nature, focusing on capturing the effects of light and portraying scenes of everyday rural and coastal life with unvarnished truthfulness.

Key figures associated with this movement included Giuseppe De Nittis (who would become a close friend of Dalbono), Marco De Gregorio, Federico Rossano, and Adriano Cecioni (who acted more as a theorist and critic for the group). Painters like Raffaele Belliazzi and Antonio Leto were also part of this milieu. Dalbono's involvement with this circle reinforced his commitment to plein air painting and his interest in depicting the authentic character of the Neapolitan region and its inhabitants, moving beyond purely picturesque representation. This experience honed his skills in capturing fleeting moments and the specific quality of Southern Italian light.

Parisian Interlude and International Exposure

Seeking broader horizons and new opportunities, Dalbono moved to Paris around 1872. The French capital was then the undisputed center of the Western art world, a hub of innovation and commercial activity. His time there, which sources suggest lasted around four years, proved pivotal. Through his friend, the increasingly successful painter Giuseppe De Nittis, Dalbono was introduced to the influential art dealer Adolphe Goupil and his firm, Goupil & Cie.

Working with Goupil provided Dalbono with significant international exposure. The gallery was a major force in the global art market, promoting artists across Europe and America. For Goupil, Dalbono produced works that capitalized on the popular demand for charming and picturesque scenes of Italian life. These Neapolitan-themed paintings, imbued with Dalbono's characteristic sensitivity to light and local color, found audiences in Britain, France, Belgium, and the Americas. This period not only broadened his reputation but also exposed him to the latest artistic developments in Paris, although his core style remained rooted in his Neapolitan origins. He would have encountered the burgeoning Impressionist movement, though his own work maintained a more structured, realist foundation compared to painters like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

Return to Naples and Mature Style

Upon returning to Naples, Dalbono re-established himself as a leading figure in the city's art scene. His mature style represented a synthesis of his diverse experiences. The foundational realism learned at the Academy and reinforced by the Resina School remained, as did the Posillipo legacy of atmospheric landscape painting. His time in Paris likely added a degree of sophistication and perhaps a brighter palette at times. However, his work increasingly took on a distinctively lyrical and poetic quality.

He became particularly adept at capturing the unique interplay of light, water, and atmosphere in the Bay of Naples. His seascapes often convey a sense of mystery and transparency, using subtle gradations of color and fluid brushwork. While grounded in observation, his landscapes often transcend mere depiction, evoking mood and emotion. Alongside his pure landscapes, he continued to explore historical and mythological themes, but often approached them through the lens of landscape and atmosphere, integrating figures seamlessly into evocative natural settings.

Themes and Subject Matter: Landscape and Legend

Dalbono's oeuvre revolved around two primary poles: the Neapolitan landscape and narratives drawn from history and myth, often intertwined.

Neapolitan Landscapes: This was arguably the heart of his production. He painted the iconic vistas of the Bay of Naples, the bustling waterfront, quiet coastal villages, and the surrounding countryside under various conditions of light and weather. Works like Barca da pesca (Fishing Boat) exemplify his interest in scenes of everyday coastal life, rendered with an eye for authentic detail and atmospheric effect. Albero di Melograni (Pomegranate Tree) showcases his ability to find beauty in specific elements of the local flora, likely depicted with the same sensitivity to light and color that characterized his broader views. His landscapes are rarely just topographical records; they are imbued with a sense of place and a personal, often romantic, response to the environment.

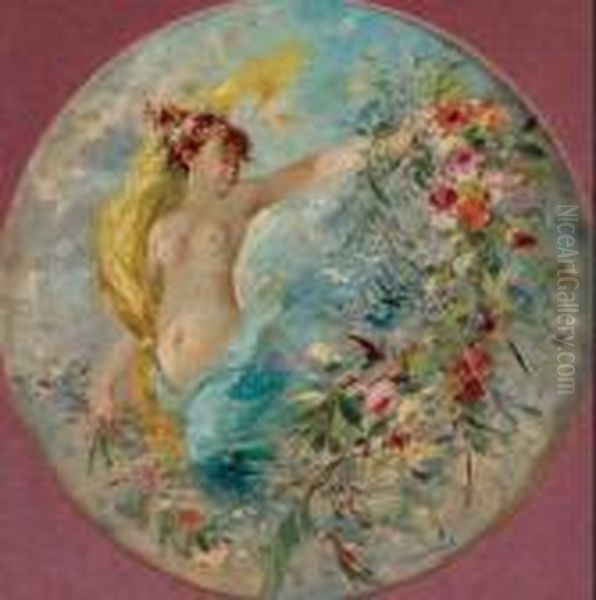

Historical and Mythological Scenes: Dalbono was drawn to the rich history and folklore of Southern Italy. He depicted historical episodes, such as La Scommessa di Re Manfredi (King Manfred's Wager), likely capturing a dramatic moment from the life of the 13th-century King of Sicily. More distinctively, he explored local myths and legends, most famously the theme of the Sirens. His painting La leggenda delle Sirene (The Legend of the Sirens), housed in the collection of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli, is a prime example. Rather than adopting a purely academic or neoclassical approach to mythology, Dalbono often set these scenes within realistic, atmospheric seascapes, blurring the lines between myth and the tangible reality of the Neapolitan coast. Works titled Gigante (Giant) or depicting Neptune (Nettuno) further point to this interest in classical and legendary figures associated with the sea, interpreted through his unique painterly vision. His Allegoria della primavera (Allegory of Spring) suggests a capacity for symbolic representation, likely combining figures with a lush, evocative landscape setting.

Academic Career and Institutional Role

Beyond his studio practice, Edoardo Dalbono played an important role in the institutional art life of Naples. His reputation and expertise led to his appointment as a Professor of Painting at the Naples Academy of Fine Arts (Regio Istituto di Belle Arti) starting in 1897. In this capacity, he influenced a new generation of Neapolitan artists, passing on his knowledge of technique and his deep understanding of the local landscape tradition. Among those who felt his influence were painters like Rubens Santoro, known for his detailed views of Venice and Naples, and Carlo Brancaccio, who inherited Dalbono's preference for landscape subjects and his approach to color.

Dalbono also held the prestigious position of Director of the Museo Artistico Industriale Filippo Palizzi in Naples, associated with the Academy (sometimes referred to as Director of the National Museum in sources, likely referring to this specific applied arts museum or a role within the broader museum context of Naples). His involvement in teaching and museum administration underscores his respected standing within the Neapolitan cultural establishment. Furthermore, some sources credit him with co-authoring a book on the Neapolitan School of the 19th century with his former mentor, Domenico Morelli, titled something akin to La Scuola di Posillipo nella pittura napoletana dell'Ottocento. While the exact details of this publication warrant careful verification, the association highlights his engagement with the art history of his own region. He was also a regular participant in exhibitions organized by the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti, a key venue for artists in Naples.

Later Years and Legacy

Edoardo Dalbono remained an active and respected painter into the early 20th century. He continued to exhibit his work and contribute to the artistic life of Naples until his death in the city in 1915, at the age of 74. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, its evocative portrayal of the Neapolitan region, and its unique blend of realism and poetic imagination.

His legacy lies primarily in his contribution to Neapolitan painting. He is considered one of the most significant interpreters of the later Posillipo tradition, adapting its focus on light and atmosphere to a more modern sensibility influenced by realism. He successfully navigated the transition from mid-19th-century styles towards the concerns of the late Ottocento, maintaining a connection to place while developing a personal and recognizable style. His depictions of the Bay of Naples, in particular, are celebrated for their atmospheric depth and lyrical beauty.

While perhaps not achieving the same level of international fame as his friend De Nittis or some of the French Impressionists he would have encountered in Paris, Dalbono holds a secure and important place in Italian art history. He stands alongside other key Neapolitan figures of his era, such as his teachers Mancinelli and Morelli, contemporaries like the Palizzi brothers (Filippo and Nicola), Gioacchino Toma, Vincenzo Gemito (the renowned sculptor), and those associated with the Resina School like Marco De Gregorio and Federico Rossano. His work influenced subsequent generations of Neapolitan painters, ensuring the continuation of a landscape tradition deeply rooted in the region's unique character.

Art Historical Significance and Evaluation

In evaluating Edoardo Dalbono's position in art history, he emerges as a pivotal figure within the specific context of Neapolitan art during a period of significant change. He was not a radical innovator in the mold of the Macchiaioli like Giovanni Fattori or Telemaco Signorini, nor did he fully embrace Impressionism. Instead, his strength lay in synthesis and refinement. He masterfully blended the atmospheric concerns of the Posillipo School with the robust realism promoted by Morelli and the Palizzi circle, adding his own distinct poetic sensibility.

His dedication to the Neapolitan landscape connects him to a long tradition, but his interpretation was personal and modern for its time. He captured not just the physical appearance of the Bay of Naples and its surroundings, but also its moods, its legends, and the quality of its light with remarkable sensitivity. His historical and mythological works are notable for their integration into these atmospheric landscapes, giving ancient stories a sense of immediacy and local grounding.

As a teacher and institutional figure, he played a vital role in shaping the next generation of artists in Naples. His influence, particularly on painters like Santoro and Brancaccio, demonstrates the respect he commanded and the relevance of his artistic vision. His works remain sought after by collectors and are held in important public collections, primarily in Italy, serving as enduring testaments to his talent and his deep connection to his native city. Edoardo Dalbono is rightly remembered as a master painter of light, atmosphere, and the enduring allure of Naples.