Ercole Gigante (1815-1860) stands as a notable figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century Italian art, particularly within the vibrant Neapolitan School of Posillipo. A dedicated landscape painter, his relatively short life was marked by a profound connection to the natural beauty of Southern Italy, a keen observational eye, and a distinctive artistic style that blended realism with a free, expressive touch. His work, though perhaps less internationally renowned than some of his contemporaries, offers a valuable insight into the artistic currents of his time and the enduring allure of the Italian landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Naples

Born in Naples in 1815, Ercole Gigante was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest years. He hailed from a family deeply rooted in the visual arts; his father, Gaetano Gigante, was himself a painter, specializing in decorative works and landscapes. This familial background undoubtedly provided Ercole with initial exposure and encouragement in his artistic pursuits. The Gigante household was a hub of creative activity, with Ercole’s brothers, Achille Gigante and Giacomo Gigante, also embarking on careers as painters. Giacomo, like Ercole, would become known for his landscape art.

Perhaps the most significant familial artistic influence on Ercole was his elder brother, Giacinto Gigante (1806-1876). Giacinto was a leading figure in the School of Posillipo and one of the most celebrated Neapolitan painters of his generation. His innovative approach to landscape, characterized by its atmospheric depth, lyrical quality, and masterful use of watercolor and oil, set a high standard and provided a powerful model for Ercole. The shared artistic passion within the Gigante family fostered an environment of mutual learning and inspiration.

Ercole's formal artistic training began under his father's tutelage. He further honed his skills through practical experience, including technical drawing at the esteemed Reale Ufficio Topografico (Royal Topographical Office) in Naples. This engagement provided him with a solid grounding in draughtsmanship and the precise rendering of form, skills that would underpin his later, more expressive landscape work. It was here he likely familiarized himself with techniques such as etching and lithography, which were crucial for cartographic and illustrative purposes.

A pivotal step in his early development was his association with the German painter Jacob Wilhelm Huber. Around 1820, Ercole, alongside his close friend Achille Vianelli, began studying with Huber, who was proficient in watercolor techniques and the use of the camera lucida. The camera lucida, an optical device, aided artists in achieving accurate perspective and outlines, a tool that many landscape painters of the era found invaluable for capturing the complexities of nature swiftly. Huber's guidance would have been instrumental in refining Ercole's watercolor skills and his approach to direct observation.

The School of Posillipo: A Crucible of Talent

To understand Ercole Gigante's artistic trajectory, one must appreciate the significance of the School of Posillipo (Scuola di Posillipo). This was not a formal academy but rather a loose collective of artists, both Italian and foreign, who were drawn to the picturesque landscapes around Naples, particularly the coastal area of Posillipo. The school flourished from the 1820s to the 1850s and represented a significant shift away from the rigid Neoclassicism that had dominated academic art.

The spiritual father of the Posillipo School was the Dutch painter Anton Sminck van Pitloo (1790-1837). Pitloo settled in Naples in 1815 and, in 1824, was appointed professor of landscape painting at the Neapolitan Academy of Fine Arts. He encouraged his students and followers to paint en plein air (outdoors), directly observing nature and capturing its fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. This approach fostered a more intimate, lyrical, and realistic depiction of the local scenery, moving away from idealized or mythological landscapes.

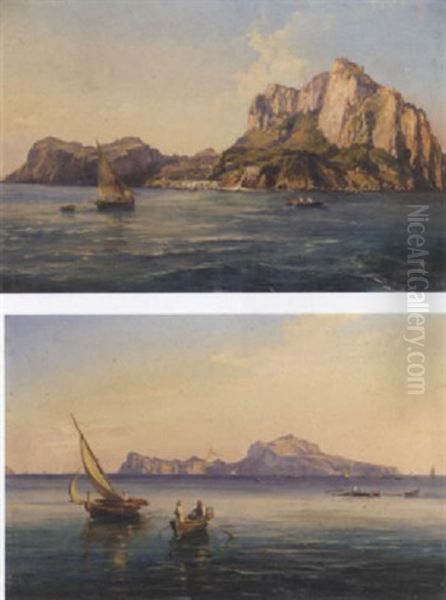

The Posillipo artists specialized in small-scale oil paintings, watercolors, and gouaches, often intended for the burgeoning tourist market. Wealthy visitors on the Grand Tour were eager to acquire mementos of their travels, and the views of Vesuvius, the Bay of Naples, Capri, Ischia, and the Amalfi Coast were highly sought after. This demand provided a livelihood for many artists and encouraged a prolific output.

Key figures associated with the School of Posillipo, besides Pitloo and the Gigante brothers (Giacinto and Ercole), included Achille Vianelli, Teodoro Duclère, Salvatore Fergola, Gabriele Carelli, Consalvo Carelli, Raffaele Carelli (the Carelli family forming another artistic dynasty), Gabriele Smargiassi, and many others. Each artist, while sharing common thematic interests and a general approach, developed individual stylistic nuances. The influence of earlier landscape traditions, such as that of the 17th-century Dutch Italianates and later masters like Jacob Philipp Hackert (who had been a court painter in Naples), was absorbed and reinterpreted through a 19th-century sensibility.

Ercole's Emergence within the Posillipo Circle

Ercole Gigante's artistic career began to gain momentum as he absorbed the lessons of his mentors and the prevailing spirit of the Posillipo School. His deep study of realism, combined with the Posillipo emphasis on direct observation, shaped his artistic vision. He made his public debut at the Bourbon Biennial exhibition in 1826, showcasing several landscape paintings, an early indication of his chosen specialization.

A significant turning point in the Posillipo School, and consequently for artists like Ercole, was the premature death of Anton Sminck van Pitloo in 1837 due to a cholera epidemic. Pitloo's passing left a void but also created opportunities for the next generation of artists to step forward. Ercole Gigante, by this time a maturing artist, became an increasingly important figure within the school. It is noted that in the same year, he moved into Pitloo's former home, a symbolic gesture perhaps, or a practical arrangement that placed him at the very heart of the Posillipo artistic community.

His style, while rooted in the Posillipo tradition, began to exhibit its own distinct characteristics. He was known for a unique color palette and a technique that balanced freedom of execution with a commitment to capturing the truth of the landscape. His brushwork could be lively and his colors vivid, conveying the bright Mediterranean light and the lushness of the Neapolitan environs.

The Pivotal Friendship and Collaboration with Achille Vianelli

One of the most defining aspects of Ercole Gigante's personal and artistic life was his profound friendship with Achille Vianelli (1803-1894). Vianelli, also a Neapolitan and a prominent member of the Posillipo School, shared many artistic sensibilities with Ercole. Their bond was not merely one of collegial respect but a deep, personal connection that fueled mutual artistic exploration.

Together, Ercole and Achille embarked on numerous sketching and painting expeditions, venturing beyond Naples to explore the diverse landscapes of Southern Italy. Their travels took them to regions such as Puglia, Lucania (modern Basilicata), and even as far as Urbino in the Marche region. These journeys were crucial for both artists, providing fresh subject matter and allowing them to refine their skills in capturing the varied topography, architecture, and local color of these areas. They would have filled sketchbooks with impressions, studies of light and shadow, and details of rural life, which would later inform their studio paintings.

Their collaborative spirit extended to professional projects. Between 1829 and 1834, Ercole Gigante and Achille Vianelli worked together on the illustrations for the "Viaggio pittorico nel regno delle due Sicilie" (Pictorial Journey in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies). This ambitious publication aimed to document the scenic beauty and historical sites of the kingdom, and the contributions of Gigante and Vianelli would have been invaluable in bringing these visions to a wider audience through prints.

The shared experiences and artistic dialogue between Gigante and Vianelli undoubtedly influenced their respective styles. Their works from this period often exhibit a similar approach to composition and a shared interest in capturing the atmospheric qualities of the landscape. Their friendship, a cornerstone of Ercole's life, tragically ended with Ercole's early death in 1860.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

Ercole Gigante's artistic style was a nuanced blend of the prevailing trends of his time and his personal vision. He was deeply committed to realism, seeking to represent the natural world with fidelity. However, his realism was not a dry, photographic transcription but was imbued with a sense of immediacy and painterly freedom. His works often display a remarkable speed of execution, with energetic brushstrokes that convey the vitality of the scene.

His color palette was a distinctive feature, often described as unique. He skillfully captured the brilliant light of Southern Italy, the azure blues of the sea and sky, the warm ochres and terracottas of the architecture, and the verdant greens of the countryside. His use of "loose colors" suggests a technique where colors might be applied with a certain fluidity, perhaps allowing for subtle blending on the canvas or paper, or juxtaposing strokes of pure color to create vibrancy.

Ercole was proficient in various media. While oil painting was a primary medium for finished works, his training with Jacob Wilhelm Huber ensured a strong command of watercolor. Watercolor, with its transparency and portability, was ideal for en plein air sketching and for capturing the ephemeral effects of light and weather. His involvement with the Reale Ufficio Topografico also indicates familiarity with printmaking techniques like etching and lithography, which, while perhaps not his primary artistic output, would have informed his understanding of line, tone, and composition.

Several key influences shaped Ercole Gigante's art. The foundational influence was, of course, his family, particularly his father Gaetano and his brother Giacinto. Giacinto Gigante's mastery of atmospheric effects and his poetic interpretation of landscape were particularly impactful. The teachings of Anton Sminck van Pitloo, the guiding spirit of the Posillipo School, provided the broader framework for his landscape approach, emphasizing direct observation and a departure from academic formalism.

The legacy of earlier landscape painters active in Naples, such as the German artist Jacob Philipp Hackert, also formed part of the artistic backdrop. Hackert, who worked for the Bourbon court in the late 18th century, produced highly detailed and classically composed landscapes that set a precedent for topographical accuracy and picturesque views, elements that the Posillipo painters, including Ercole, adapted to their more romantic and immediate style. Furthermore, the presence of other talented contemporaries within the Posillipo circle, such as Teodoro Duclère, Salvatore Fergola, and the various members of the Carelli family (Gabriele, Consalvo, Raffaele), created a stimulating environment of shared ideas and friendly rivalry. One might also consider the broader European context, where artists like J.M.W. Turner and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot were revolutionizing landscape painting; their visits to Italy and the dissemination of their work could have indirectly influenced the Neapolitan scene.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

While a comprehensive catalogue of Ercole Gigante's oeuvre might be challenging to assemble due to the nature of Posillipo School production (many works were unsigned or sold directly to tourists), several pieces and general themes are associated with him.

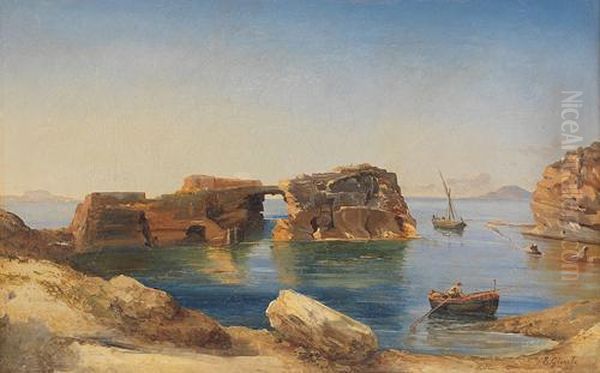

One of his specifically mentioned representative works is "Marina" (Seascape), an oil painting dated 1860, the year of his death. Measuring 25.8 x 41 cm, this work, signed and dated in the lower left, would encapsulate his mature style. A "Marina" by a Posillipo painter would typically depict a coastal scene, perhaps featuring fishing boats, a bustling quayside, or a tranquil view across the Bay of Naples, possibly with Vesuvius in the background. One can imagine Ercole's "Marina" to be characterized by his lively brushwork, his keen sense of light reflecting on the water, and a composition that balances topographical accuracy with artistic expression. The reported valuation of such a piece (€18,000-€22,000) indicates the esteem in which his work is held by collectors.

Another cited work is "Corpo di Cava." This title likely refers to views of Cava de' Tirreni, a town near Salerno, famous for its Benedictine abbey, La Trinità della Cava. This area, with its dramatic mountain scenery, lush valleys, and historic architecture, was a popular subject for landscape painters. Ercole's depiction would have focused on capturing the unique character of this location, perhaps highlighting the interplay of natural landscape and human presence.

Beyond specific titles, Ercole Gigante's thematic concerns were typical of the Posillipo School. He painted the iconic views of Naples and its surroundings: the sweeping Bay, the imposing silhouette of Vesuvius (both dormant and erupting), the charming coastal towns like Sorrento and Amalfi, and the idyllic islands of Capri and Ischia. His travels with Vianelli would have expanded his repertoire to include scenes from Puglia, with its distinctive trulli and sun-drenched plains, and the rugged landscapes of Lucania. These works collectively celebrate the natural beauty and cultural richness of Southern Italy.

His paintings were not just topographical records; they aimed to evoke a mood, a sense of place, and the particular quality of Mediterranean light. The "truthfulness of landscape" and "capturing the moment" were paramount, suggesting an interest in the transient effects of weather and time of day, hallmarks of en plein air painting.

Later Years, Educational Aspirations, and Untimely Death

In his later years, Ercole Gigante reportedly shifted some of his focus towards education within the Posillipo School. Having benefited from the guidance of others and having established himself as a respected artist, he may have felt a desire to nurture the next generation of painters. The Posillipo School, being an informal collective, would have relied on such mentorship from its senior members.

His commitment to teaching, however, was tragically cut short. Ercole Gigante died in 1860 at the relatively young age of 45. His premature death meant that his full potential as an artist and as an educator may not have been realized. The information suggests he had plans to make significant contributions to the Posillipo School's educational aspect, aspirations that remained unfulfilled.

His death also marked the end of his close and artistically fruitful friendship with Achille Vianelli. The loss would have been felt keenly within the Neapolitan artistic community, which was already witnessing a gradual evolution as new artistic movements began to emerge in Italy.

Legacy and Significance

Ercole Gigante's legacy lies in his contribution to the School of Posillipo and, more broadly, to 19th-century Neapolitan landscape painting. While perhaps overshadowed by his more famous brother Giacinto, or by the founding figure of Pitloo, Ercole carved out his own niche with his distinctive style, characterized by its vibrant color, energetic execution, and sincere engagement with nature.

His works, like those of his Posillipo colleagues, played a crucial role in popularizing the landscapes of Southern Italy, both domestically and internationally. They catered to the romantic sensibilities of the era and the desires of Grand Tour travelers, helping to shape the visual identity of Naples and its environs in the popular imagination. These paintings, often intimate in scale, offered a more personal and accessible vision of Italy than the grand historical or mythological canvases favored by academic tradition.

The emphasis of the Posillipo School on direct observation and en plein air painting was a significant step towards modernism in Italian art. Artists like Ercole Gigante, by prioritizing the empirical study of nature and the subjective response of the artist, contributed to a broader shift away from idealized, studio-bound conventions. This approach laid some of the groundwork for later movements, such as the Macchiaioli in Tuscany, who also championed painting from life and a revolutionary use of color and form.

Today, Ercole Gigante's paintings are found in private collections and public institutions, particularly in Italy. They are valued for their artistic merit, their historical importance as documents of the Posillipo School, and their evocative portrayal of a beloved region. Art historians and connoisseurs recognize his skill in capturing the unique atmosphere of Naples, his adept handling of oil and watercolor, and his role within a family that contributed significantly to the artistic heritage of the city.

Conclusion

Ercole Gigante was a dedicated and talented artist whose life and work were inextricably linked to the city of Naples and the picturesque landscapes of Southern Italy. As a key member of the School of Posillipo, he embraced the ethos of direct observation and expressive freedom, creating paintings that are both topographically informative and aesthetically pleasing. His collaborations, particularly with Achille Vianelli, and his place within the artistic Gigante family, highlight the interconnectedness of the Neapolitan art world in the 19th century.

Though his career was cut short by his untimely death, Ercole Gigante left behind a body of work that continues to charm and engage viewers. His landscapes serve as a vibrant testament to his skill, his love for his native region, and his contribution to a significant chapter in the history of Italian art. He remains an important figure for understanding the evolution of landscape painting in Naples and the enduring appeal of capturing the "spirit of place" on canvas.