Eduard von Gebhardt stands as a significant figure in 19th and early 20th-century German art, particularly renowned for his historical and religious paintings. Born Franz Karl Eduard von Gebhardt on June 13, 1838, in Järva-Jaani (St. Johannis), Estonia, then part of the Russian Empire, he emerged from a Baltic German heritage that would subtly inform his artistic perspective. His father's role as a Protestant pastor undoubtedly played a part in shaping Gebhardt's lifelong engagement with religious themes, which he approached with a distinctive blend of realism and historical consciousness. His career, primarily centered in Düsseldorf, saw him become an influential professor and a key proponent of a style that looked to the masters of the German and Netherlandish Renaissance and Baroque periods for inspiration, moving away from the prevailing academic romanticism of his earlier contemporaries.

Early Life and Formative Artistic Education

Eduard von Gebhardt's artistic journey began in earnest at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, where he studied from 1855 to 1858. This initial training provided him with a foundational understanding of academic principles. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation, Gebhardt sought broader exposure and further refinement of his skills. His travels led him to Vienna, a vibrant artistic hub, and then to Karlsruhe. In Karlsruhe, he likely encountered the influence of artists associated with its academy, possibly studying under figures like Hans Fredrik Gude, known for his landscape painting, though Gebhardt's own path would lead him more towards figure and historical compositions. These early experiences were crucial in shaping his technical abilities and exposing him to different artistic currents circulating in Europe.

The pivotal moment in his early career came in 1860 when he arrived in Düsseldorf. This city was home to the renowned Düsseldorf Academy of Arts, a leading art school in Europe, famous for the Düsseldorf School of painting. Here, Gebhardt became a student of Wilhelm Sohn, a respected professor at the Academy known for his genre and historical paintings. Sohn's tutelage would have reinforced Gebhardt's inclination towards narrative and historical subjects, providing him with the rigorous training in drawing and composition that was a hallmark of the Düsseldorf tradition.

The Düsseldorf School and Gebhardt's Emergence

The Düsseldorf School of Painting, flourishing since the 1820s under figures like Peter von Cornelius and later, more significantly, Wilhelm von Schadow, had established an international reputation. It was known for its detailed realism, often applied to historical, mythological, genre, and landscape scenes. Artists like Andreas Achenbach and Oswald Achenbach (landscape), Karl Friedrich Lessing (history and landscape), and Ludwig Knaus (genre) were prominent figures associated with the school, creating a rich artistic environment. Gebhardt entered this milieu at a time when the initial romantic impulses of the school were evolving.

Gebhardt quickly absorbed the technical proficiency emphasized at Düsseldorf but began to carve out his own distinct artistic identity. He did not merely replicate the established styles but sought a more profound and historically grounded approach, particularly in his religious art. His decision to settle permanently in Düsseldorf after his studies underscored the city's importance to his development and career. The supportive, if sometimes competitive, environment of the Düsseldorf art scene provided both a platform and a challenge for the young artist.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Realism and Historical Consciousness

Eduard von Gebhardt's mature artistic style is characterized by a profound engagement with realism, yet it is a realism deeply informed by historical study and a desire to convey psychological depth. He became a leading innovator in German religious art, consciously breaking away from the idealized and often sentimental approach of the Nazarene movement, which had been influential earlier in the 19th century. Artists like Friedrich Overbeck and Franz Pforr, key figures of the Nazarenes, had sought a revival of Christian art based on early Italian Renaissance models. Gebhardt, however, found his primary inspiration in the robust and characterful art of 16th and 17th-century German and Dutch masters.

His study of artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and particularly Rembrandt van Rijn, was transformative. From these masters, he absorbed a commitment to verisimilitude, a focus on individual character, and a dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), especially evident in his Rembrandtesque influences. Gebhardt sought to imbue his religious figures with a sense of tangible reality and emotional sincerity, often clothing them in historically accurate 16th-century German attire, thereby connecting the biblical past with a specifically German cultural heritage, particularly that of the Reformation era. This approach lent his sacred scenes an immediacy and relatability that was novel for its time. His realism extended to the depiction of peasants and everyday life, reflecting a broader 19th-century interest in genre scenes, but always with a dignified and often solemn tone.

Key Thematic Concerns: Reinterpreting Religious Narratives

Religious subjects formed the core of Gebhardt's oeuvre. Influenced by his Protestant upbringing and the humanistic currents of his time, he approached biblical narratives not merely as illustrations of dogma but as profound human dramas. He aimed to strip away layers of later idealization and present these stories with a stark, often austere, honesty. His figures are not ethereal saints but recognizable human types, grappling with faith, doubt, and suffering. This approach was particularly evident in his depictions of Christ and the Apostles, whom he often portrayed with a rugged, peasant-like quality, emphasizing their humble origins and the earthy reality of their mission.

His commitment to historical accuracy in costume and setting was not merely an academic exercise; it was a means of making the sacred past resonate with contemporary audiences, particularly within a German Protestant context. By situating biblical events within a visual framework reminiscent of the German Renaissance and Reformation, he tapped into a deep cultural memory. This was a significant departure from the Italianate or classical idealizations that had long dominated religious art. His work often explored themes of piety, contemplation, and the human condition in the face of divine mystery.

Major Works: Milestones in a Distinguished Career

Eduard von Gebhardt's extensive body of work includes numerous paintings that garnered critical acclaim and cemented his reputation.

One of his early significant works, Christ Entering Jerusalem (c. 1863-1870), showcased his emerging style, blending historical detail with a solemn, narrative power. The figures are individualized, and the composition is carefully structured to convey the gravity of the event.

Around 1870, he painted The Last Supper, a work often cited as a turning point, clearly demonstrating his preference for Old German costume and a more realistic, less idealized portrayal of the apostles. This work, along with others from this period, established him as a distinct voice in religious painting.

The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896) is another powerful example of his ability to convey intense emotion and spiritual drama through realistic depiction. The expressions of the onlookers and the central figures capture the awe and wonder of the miracle.

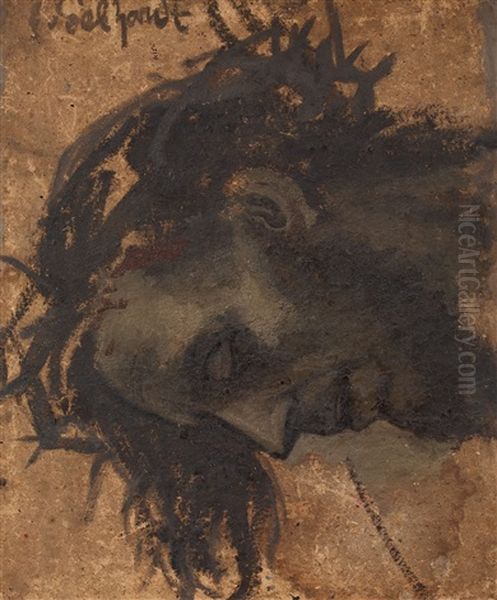

His Sermon on the Mount (c. 1902) and Ecce Homo (c. 1889) further exemplify his mature style, characterized by strong characterization, a subdued but rich palette, and a focus on the psychological and spiritual import of the scenes.

Beyond easel paintings, Gebhardt also undertook significant mural projects. His work in the Loccum Abbey, a former Cistercian monastery in Lower Saxony, involved creating large-scale biblical scenes, demonstrating his ability to adapt his style to monumental formats. He also painted murals for the Friedenskirche (Church of Peace) and the Petrikirche (St. Peter's Church) in Düsseldorf, contributing to the city's public and sacred art.

While religious themes dominated, Gebhardt also engaged with contemporary historical events. The Wounded of Gravelotte, inspired by the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), shows his capacity for depicting the human cost of conflict with empathy and realism. This painting was notably acquired by Kaiser Wilhelm I. He was also a skilled portraitist, capturing the likeness and character of his sitters, and even designed bookplates (ex-libris), showcasing his versatility. Works like Evening Prayer and Mother and Child highlight his ability to find dignity and spiritual resonance in simpler, more intimate scenes of peasant life and domestic piety.

A Professor of Renown: Shaping a Generation at the Düsseldorf Academy

In 1873, Eduard von Gebhardt's contributions to art were formally recognized with his appointment as a professor at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts. This marked the beginning of a long and influential teaching career that spanned 38 years, until his retirement in 1914. As a professor, Gebhardt exerted considerable influence on a generation of artists. His teaching methods were known to be rigorous and demanding. He emphasized the importance of drawing from life, meticulous study of the human form, and a deep understanding of historical styles.

Reports suggest he was a strict instructor, sometimes employing direct, even physical, intervention to correct a student's work, a practice not uncommon in art academies of the period but indicative of his passionate commitment to artistic standards. He encouraged his students to develop their own voices while grounding them in solid technical skills. Among his students was the Brazilian-German painter Wilhelm Techmeier, who would have carried Gebhardt's influence into his own artistic practice.

His role as a professor was not in isolation. He worked alongside other distinguished faculty at the Düsseldorf Academy, such as the landscape painter Eugen Dücker. Together, they contributed to maintaining the Academy's reputation as a leading center for art education, even as new artistic movements like Impressionism began to challenge academic traditions elsewhere in Europe. Gebhardt's dedication to teaching ensured that his artistic principles and his unique approach to historical and religious painting were passed on, influencing the trajectory of German art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Broader Artistic Landscape and Gebhardt's Position

Eduard von Gebhardt's career unfolded during a period of significant artistic change in Europe. While he remained rooted in the traditions of realism and historical painting, he was not oblivious to the shifts occurring around him. The rise of Impressionism, championed by artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro in France, and later by German artists such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt, introduced new ways of seeing and representing the world, emphasizing light, color, and fleeting moments.

In Germany itself, artists like Wilhelm Leibl, a contemporary, were also pursuing a powerful form of realism, often focusing on peasant life with an unvarnished truthfulness. Within the realm of religious art, Fritz von Uhde, another contemporary, was also innovating by depicting biblical scenes in contemporary settings with modern dress, creating a different kind of immediacy than Gebhardt's historical approach.

Gebhardt's position within this evolving landscape was that of a respected master who upheld the value of narrative, historical consciousness, and technical skill, while also innovating within the genre of religious painting. He offered an alternative to both the lingering sentimentality of late Romanticism and the more radical departures of the avant-garde. His commitment to a German-Netherlandish lineage, rather than a purely classical or Italianate one, also distinguished his work and resonated with a sense of national artistic identity. His influence can be seen as a counterpoint to the more internationalist trends, providing a strong, regionally rooted artistic vision.

Anecdotes and Personal Dimensions

While detailed personal anecdotes about Eduard von Gebhardt are not extensively documented in the readily available sources, certain aspects of his professional life offer glimpses into his character. His reported strictness as a teacher, including the occasional physical correction of student work, paints a picture of an artist deeply serious about his craft and committed to high standards. This intensity was likely balanced by a profound dedication to his students' development.

His repeated returns to his Estonian homeland for study suggest a deep connection to his roots and a desire to incorporate authentic local character into his depictions of peasant life, even if his primary subjects were often biblical. This practice aligns with the 19th-century realist impulse to ground art in observed reality. The fact that he designed bookplates indicates a broader artistic sensibility, extending beyond large-scale canvases to more intimate forms of graphic art. His long and stable career in Düsseldorf, a major artistic center, points to a life dedicated to the steady pursuit of his artistic vision and the education of others.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Eduard von Gebhardt continued to paint and teach into the early 20th century, retiring from his professorship at the Düsseldorf Academy in 1914, on the cusp of the First World War, a conflict that would irrevocably change the European cultural landscape. He passed away on February 3, 1925, in Düsseldorf, the city that had been his artistic home for over six decades.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he revitalized religious art in Germany by infusing it with a new realism and historical depth, drawing inspiration from Northern European masters. He successfully created a visual language for Protestant religious themes that was both dignified and accessible. His works are found in major German museums and collections, attesting to his contemporary significance and enduring appeal.

As a teacher, his impact was profound. For nearly four decades, he shaped the artistic development of countless students at one of Europe's leading art academies. His emphasis on technical skill, historical understanding, and sincere expression left an indelible mark on the Düsseldorf School and on German art more broadly. While artistic styles continued to evolve rapidly after his death, Gebhardt's contribution as a master of historical and religious painting, and as a dedicated educator, remains a significant chapter in the history of 19th and early 20th-century art. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of narrative art grounded in human experience and historical consciousness.

Conclusion

Eduard von Gebhardt was more than just a skilled painter; he was a thoughtful interpreter of history and faith, a bridge between the rich traditions of Northern European art and the evolving sensibilities of his own time. His decision to eschew the prevailing Nazarene idealism in favor of a robust, character-driven realism inspired by masters like Rembrandt and Dürer marked a significant shift in German religious art. By situating biblical narratives within a recognizably German historical context, he made these ancient stories resonate with a new immediacy and cultural relevance. His long tenure as a professor at the Düsseldorf Academy ensured that his artistic principles and rigorous approach to craftsmanship were transmitted to a new generation, solidifying his influence. In an era of burgeoning modernism, Gebhardt steadfastly upheld the values of narrative clarity, psychological depth, and historical integrity, leaving behind a body of work that continues to command respect for its artistic power and spiritual sincerity.