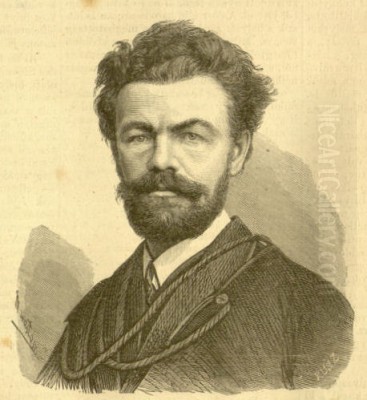

Mihaly Munkacsy stands as one of the most significant figures in Hungarian art history and a prominent exponent of 19th-century European Realism. Born Mihály Lieb on February 20, 1844, in Munkács, Kingdom of Hungary (now Mukachevo, Ukraine), his life journey took him from humble, challenging beginnings to the pinnacle of international artistic fame. Renowned for his powerful genre scenes, dramatic historical and religious canvases, and insightful portraits, Munkacsy captured the complexities of the human condition with profound empathy and technical brilliance. His work resonated deeply with contemporary audiences and continues to be celebrated for its emotional intensity and masterful execution. This exploration delves into the life, artistic development, key works, relationships, and enduring legacy of this remarkable painter.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Munkacsy's early life was marked by hardship. He came from a family of Bavarian origin, and tragedy struck early when he lost both his parents. Orphaned at a young age, he was raised by relatives and initially apprenticed to a carpenter. This practical, hands-on work might seem far removed from the world of fine art, but it perhaps instilled in him a sense of discipline and materiality. However, his artistic inclinations soon became apparent. Despite the lack of formal encouragement initially, his desire to draw and paint persisted.

His journey towards becoming an artist began in earnest when he managed to find opportunities for rudimentary training. He encountered the itinerant painter Elek Szamossy, who recognized his potential and provided him with his first formal lessons around 1863. This mentorship was crucial, offering Munkacsy foundational skills and encouragement to pursue art more seriously. Szamossy's guidance helped him navigate the initial steps away from provincial life towards the centers of artistic learning.

Seeking better opportunities, Munkacsy moved to Pest (now part of Budapest) around 1864. There, he sought to immerse himself in the city's nascent art scene. He met established artists like the landscape painter Antal Ligeti and potentially others like Károly Lotz, absorbing what he could from the environment. During this period, he likely supported himself through various means, possibly including portrait commissions or decorative work, while continuing to hone his skills. His determination was evident as he navigated the challenges of poverty and lack of connections.

Formal Training and Formative Influences

Recognizing the need for more structured education, Munkacsy sought admission to major European art academies. With the help of patrons who recognized his talent, he first traveled to Vienna in 1865 to study at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). Vienna exposed him to a wider range of historical and contemporary art, broadening his horizons beyond the Hungarian context. The academic training emphasized drawing from casts and live models, providing a rigorous foundation in anatomy and composition.

His quest for knowledge and stylistic development led him further afield. In 1866, he moved to Munich, a major center for historical painting and emerging realist trends in Germany. He studied at the Munich Academy, where influential figures like Karl von Piloty championed a form of historical realism characterized by dramatic staging and meticulous detail. While not directly Piloty's student for long, the prevailing atmosphere undoubtedly influenced his approach to narrative painting. He also encountered the works of German realists who focused on everyday life.

A pivotal move occurred in 1868 when Munkacsy relocated to Düsseldorf. There, he studied privately with Ludwig Knaus, a renowned genre painter known for his depictions of peasant life. This period was significant for Munkacsy's development towards genre painting with a strong narrative and psychological component. Düsseldorf, with its tradition of detailed, anecdotal painting, provided fertile ground for his burgeoning style. It was here that he began to synthesize academic discipline with a growing interest in portraying authentic human emotion and social realities. He also became acquainted with the darker, more tonal palette favored by some Düsseldorf artists, which would become a hallmark of his early masterpieces.

Breakthrough: The Last Day of a Condemned Man

The turning point in Munkacsy's career arrived dramatically in 1869-1870 with the creation of Siralomház (The Condemned Cell), better known internationally as The Last Day of a Condemned Man. Painted during his time in Düsseldorf, this large-scale canvas depicted a prisoner in his cell shortly before execution, surrounded by a few visitors and onlookers. The painting was a stark departure from sentimental genre scenes; it confronted viewers with raw human despair, psychological tension, and the grim reality of capital punishment.

The work's power lay in its unflinching realism and profound empathy. Munkacsy employed a dramatic chiaroscuro, focusing light on the condemned man's pale face and slumped figure, while shrouding much of the surrounding scene in deep shadow. The varied reactions of the other figures – grief, curiosity, official indifference – added layers of narrative complexity. The painting showcased his mastery of composition, anatomical accuracy, and, most importantly, his ability to convey intense emotion through gesture and expression.

Submitted to the prestigious Paris Salon of 1870, The Last Day of a Condemned Man caused a sensation. It was awarded the Gold Medal, instantly catapulting the young Hungarian painter to international fame. Critics lauded its power, originality, and technical skill. This success was transformative, opening doors to patronage, commissions, and recognition within the highest echelons of the European art world. The painting established Munkacsy as a major new voice in realist painting, one capable of tackling profound themes with dramatic force.

Consolidation of Style: Realism and Narrative Depth

Following the triumph of The Last Day of a Condemned Man, Munkacsy continued to explore themes of human struggle, labor, and social commentary, solidifying his distinctive realist style. His work during the early 1870s often featured dark, bituminous tones, dramatic lighting reminiscent of Rembrandt, and a focus on the psychological state of his subjects. He drew inspiration from earlier masters but also aligned himself with contemporary realist movements across Europe.

His approach was deeply influenced by the French Realists, particularly Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. Like Courbet, Munkacsy often chose subjects from ordinary life and depicted them with unvarnished honesty. From Millet, he absorbed a profound sympathy for the rural poor and working classes, often portraying their dignity amidst hardship. However, Munkacsy's realism possessed a unique theatricality and emotional intensity that set it apart.

Another significant work from this period is Making Lint (Tépéscsinálók, 1871), sometimes interpreted as Milton Dictating Paradise Lost to his Daughters. This painting depicts women diligently preparing lint for bandages, likely for wounded soldiers. While seemingly a simple genre scene, it carries undertones of quiet suffering, duty, and the unseen labor supporting larger historical events. The composition, lighting, and focus on the figures' expressions elevate the scene beyond mere documentation, imbuing it with pathos. Some interpretations link the central, perhaps blind, figure to the poet Milton, adding layers of meaning about creativity, loss, and resilience, possibly reflecting Munkacsy's own struggles and ambitions.

The Paris Years: Fame, Fortune, and Artistic Evolution

In 1872, Munkacsy moved to Paris, the undisputed capital of the 19th-century art world. His success at the Salon had paved the way, and he quickly established himself as a leading figure. In 1874, he married the wealthy widow Cécile Papier, Baroness de Marches. This marriage brought financial security and entry into high society. The couple maintained a lavishly furnished studio and home, which became a prominent social center, frequented by artists, writers, musicians, and collectors.

This period marked a shift in Munkacsy's life and, to some extent, his art. While he continued to produce powerful genre scenes and historical paintings, he also began painting elegant Parisian interiors, society portraits, and still lifes, catering to the tastes of his wealthy clientele. These works often featured brighter colors and a more polished finish compared to his earlier, darker canvases. Some critics lamented this perceived move towards more commercially appealing subjects, but Munkacsy never entirely abandoned the social and psychological themes that defined his early work.

Living in Paris placed him at the heart of artistic debates and developments. He witnessed the rise of Impressionism but remained largely committed to his realist principles, though his brushwork occasionally showed a looser, more painterly quality in his later works. His international reputation grew steadily, with exhibitions across Europe and America. He became one of the most famous and highly paid painters of his time, a remarkable achievement for someone from his background. Despite his fame and integration into Parisian life, he maintained strong ties to Hungary and never relinquished his Hungarian identity, reportedly refusing French citizenship.

Monumental Ambitions: The Christ Trilogy

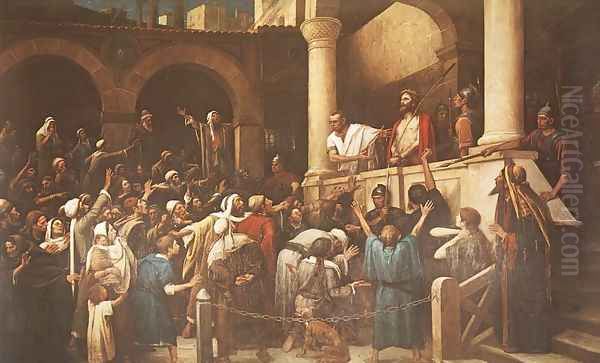

Perhaps the most ambitious undertaking of Munkacsy's career was his religious trilogy depicting key moments from the Passion of Christ. These monumental canvases cemented his international fame, particularly in the United States, and represented the culmination of his interest in historical drama and profound human emotion. The trilogy consists of Christ before Pilate (1881), Golgotha (also known as Christ on Calvary, 1884), and Ecce Homo (1896).

Christ before Pilate was the first of the series and achieved enormous success. Depicting the tense confrontation between a serene, resigned Christ and the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, surrounded by a tumultuous crowd, the painting masterfully orchestrates a complex scene with numerous figures. Munkacsy's skill in rendering individual reactions – skepticism, fury, piety, indifference – creates a powerful psychological drama. The painting toured Europe and America to great acclaim and was eventually purchased by the American department store magnate John Wanamaker.

Golgotha, completed three years later, portrays the Crucifixion itself. It is a harrowing depiction of suffering and grief, focusing on the central figure of Christ on the cross against a dark, stormy sky, with mourners gathered at the base. The raw emotion and dramatic intensity are characteristic of Munkacsy's style. Like its predecessor, Golgotha toured internationally and was also acquired by Wanamaker.

The final painting, Ecce Homo ("Behold the Man"), completed much later in 1896 when Munkacsy's health was already declining, shows Pilate presenting the scourged Christ to the hostile crowd. It revisits the themes of judgment, suffering, and mob mentality explored in the first painting, bringing the narrative cycle to a powerful conclusion. The entire trilogy, often exhibited together, captivated audiences with its scale, realism, and emotional impact, solidifying Munkacsy's reputation as a master of historical and religious painting.

Controversy and Context: The Trilogy and Tiszaeszlár

Munkacsy's Christ before Pilate became entangled, at least in critical interpretation, with a contemporary event in Hungary: the Tiszaeszlár affair of 1882-1883. This notorious case involved accusations of ritual murder against Jewish residents of the village of Tiszaeszlár, fueling a wave of anti-Semitism in Hungary and beyond. Although the accused were eventually acquitted, the affair left deep scars.

Some historians and art critics have suggested that the depiction of the crowd demanding Christ's crucifixion in Christ before Pilate might have resonated with, or even been influenced by, the anti-Semitic fervor surrounding the Tiszaeszlár case. The portrayal of the Jewish figures in the crowd has been scrutinized for potentially reinforcing negative stereotypes prevalent at the time. Whether Munkacsy intended such a connection is debated, but the painting's creation and reception occurred within this charged historical context, adding a layer of complexity and controversy to its interpretation. This highlights how major artworks can intersect with and reflect the social and political tensions of their era.

Versatility: Genre Scenes, Landscapes, and Portraits

While Munkacsy is best known for his large-scale dramatic works, his oeuvre demonstrates considerable versatility. He continued to paint genre scenes throughout his career, often depicting Hungarian peasant life with warmth and empathy. Works like Dusty Road or scenes of village interiors capture the textures and rhythms of rural existence. These paintings often display a lighter palette and looser brushwork compared to his major historical canvases.

He also produced striking portraits, capturing the likeness and personality of prominent figures as well as intimate studies of family and friends. His portraits often combine psychological insight with a sophisticated handling of light and texture, reflecting both his academic training and his realist sensibilities.

Landscape painting was another area of interest, particularly during his association with the Hungarian painter László Paál. Paál was deeply connected to the French Barbizon School, known for its realistic and atmospheric depictions of nature. Munkacsy and Paál were close friends, even sharing a studio for a time. Influenced by Paál and the Barbizon aesthetic, Munkacsy painted evocative landscapes, such as Sunset in the Forest, characterized by their moody atmosphere and sensitivity to light effects. These works reveal a more lyrical side of his artistic personality.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Munkacsy's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships, encompassing mentors, peers, influences, and those he influenced. His early guidance from Elek Szamossy and encounters with Pest artists like Antal Ligeti were formative. His studies in Vienna, Munich (under the influence of Piloty's school), and Düsseldorf (with Ludwig Knaus) connected him to major currents in German academic and realist art.

His move to Paris brought him into contact with the French art world. While maintaining his own style, he was undoubtedly aware of the Impressionists and other avant-garde movements. His relationship with French Realists like Courbet and Millet was one of influence and shared sensibility, focusing on themes of labor and social reality. His friendship with the landscape painter László Paál connected him to the Barbizon tradition.

Munkacsy's fame also attracted younger artists. The most notable example is the German painter Max Liebermann. As a student, Liebermann greatly admired Munkacsy's work, particularly The Last Day of a Condemned Man. In 1871, Liebermann traveled with his friend, the painter Theodor Hagen, to see Munkacsy's work exhibited in Regensburg, an event organized by Stanislaus von Kalckreuth, the director of the Weimar Art Academy. Liebermann later visited Munkacsy's studio in Düsseldorf. Munkacsy's dramatic realism and choice of subject matter significantly impacted Liebermann's early works, such as Women Plucking Geese (1872), which Liebermann himself acknowledged as a response to Munkacsy. While the exact nature of their relationship is debated (teacher-student or simply mutual respect), Munkacsy's influence on the early Liebermann is undeniable.

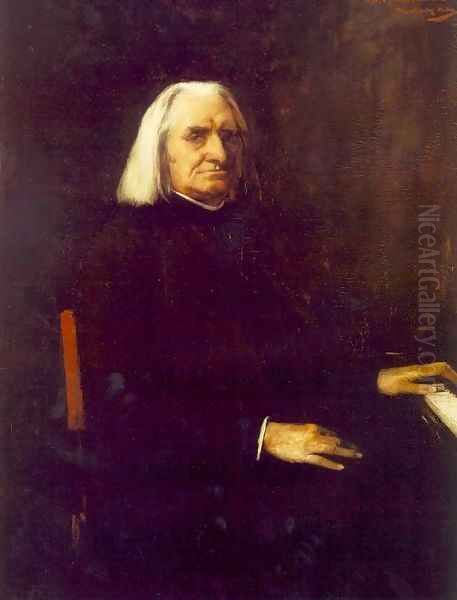

Beyond painters, Munkacsy cultivated relationships with figures in other cultural fields. His friendship with the celebrated Hungarian composer Franz Liszt is well-documented. Liszt admired Munkacsy's work and supported his career. They moved in similar cosmopolitan circles, and Liszt reportedly attended events celebrating Munkacsy's achievements, such as a reception for Golgotha in Budapest. This connection highlights Munkacsy's integration into the broader European cultural elite.

Later Life, Illness, and Death

Despite his immense success, Munkacsy's later years were overshadowed by declining health. From the mid-1890s, he began suffering from increasing mental distress and physical ailments, often attributed to syphilis, a disease prevalent at the time and notoriously difficult to treat. His condition deteriorated significantly after the completion of Ecce Homo in 1896.

His illness impacted his ability to work and led to periods of instability. He spent his final years in sanatoriums, first in Baden-Baden and later in Endenich, near Bonn, Germany. His creative output ceased, and his public appearances became rare. Mihaly Munkacsy died in the Endenich sanatorium on May 1, 1900, at the age of 56. His death marked the end of a remarkable artistic journey that had taken him from obscurity to global renown. He was given a state funeral in Budapest, a testament to his status as a national cultural hero in Hungary.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Mihaly Munkacsy left an indelible mark on Hungarian and European art. He is widely regarded as Hungary's most important historical painter, a national icon whose work embodies both artistic excellence and a deep connection to Hungarian identity, despite his spending much of his career abroad. His powerful realism, dramatic storytelling, and psychological depth influenced subsequent generations of Hungarian artists who sought to create a distinctly national art.

His impact extended beyond Hungary. His success on the international stage, particularly at the Paris Salon and through the tours of his Christ Trilogy in America, demonstrated that artists from smaller European nations could achieve global recognition. He played a significant role in popularizing realist painting that engaged with social, historical, and religious themes in a dramatic and emotionally resonant manner. His influence on artists like Max Liebermann illustrates his reach within the broader European context.

Munkacsy's works are housed in major museums worldwide, including the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, and various collections in the United States. The Déri Museum in Debrecen, Hungary, holds the Christ Trilogy, which remains a major cultural attraction. The Munkácsy Mihály Museum in Békéscsaba, a city with ties to his family, is dedicated to his life and work. His paintings continue to be studied and admired for their technical mastery and enduring humanism. Issues surrounding the ownership and preservation of his major works, such as the state's intervention to keep Golgotha in Hungary, underscore his continued importance as a national treasure.

Conclusion: A Master of Drama and Humanity

Mihaly Munkacsy's life and art encapsulate a compelling narrative of talent, ambition, and the power of painting to explore the depths of human experience. From his challenging origins, he rose through determination and extraordinary skill to become one of the most celebrated painters of his era. His commitment to realism was infused with a unique sense of drama and psychological intensity, allowing him to create works that resonated powerfully with contemporary audiences and continue to engage viewers today.

Whether depicting the final moments of a condemned prisoner, the monumental events of the Passion, the quiet dignity of peasant life, or the elegance of Parisian society, Munkacsy brought a profound empathy and technical brilliance to his subjects. He navigated the complexities of the 19th-century art world, achieving international fame while remaining deeply connected to his Hungarian roots. His legacy endures not only in his magnificent canvases but also in his influence on subsequent artists and his revered status as a pivotal figure in the history of European art. Munkacsy remains a testament to the enduring power of realist painting to capture both the specific realities of an era and the universal truths of the human condition.