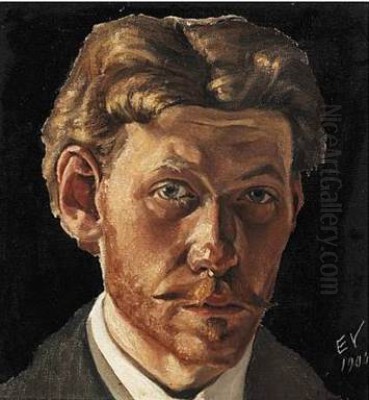

Viggo Thorvald Edvard Weie, a name that resonates with the vibrant evolution of Danish art in the early 20th century, stands as a seminal figure in the narrative of Scandinavian modernism. Born on November 18, 1879, in Copenhagen, and passing away on April 9, 1943, in Frederiksberg, Weie's life and work encapsulate the struggles, breakthroughs, and profound intellectual depth of an artist grappling with new forms of expression. His journey from a childhood marked by hardship to becoming one of Denmark's most revered modern painters is a testament to his unwavering dedication and unique artistic vision. Weie's legacy is characterized by his intense exploration of color, his gradual shift towards abstraction, and his often-critical engagement with the art world of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Edvard Weie's early years were far from privileged. His father, a man of uncertain profession, abandoned the family when Edvard was very young, plunging them into considerable poverty. This challenging start in life undoubtedly shaped Weie's resilient character. To support his family and his burgeoning desire for education, the young Weie took on work delivering newspapers and later served as a house painter's apprentice. These experiences, while demanding, did not extinguish his artistic flame. Instead, they seem to have fueled a determination to pursue a path less ordinary.

His ambition led him to apply to the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. However, his initial attempts were met with rejection, a common experience for many artists who would later redefine artistic conventions. Undeterred, Weie continued to hone his skills independently, driven by an inner calling. This period of self-study and practical work laid a foundational understanding of materials and a disciplined work ethic that would serve him throughout his career.

Formal Training and Early Influences

A significant turning point came in 1905 when Edvard Weie was finally able to enroll in a formal art education setting. He joined the Kunstnernes Frie Studieskoler (The Artists' Free Study Schools), an alternative art school that had become a vital hub for progressive artistic thought in Copenhagen. Here, he studied under the tutelage of Kristian Zahrtmann, a highly influential and somewhat eccentric figure in Danish art. Zahrtmann was known for his historical paintings, his bold use of color, and his encouragement of individualism among his students.

Under Zahrtmann's guidance, Weie had the opportunity to travel to Italy in 1907. This journey, a traditional rite of passage for many Northern European artists, was intended to expose him to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and the classical world, as well as the vibrant Italian light and landscape. However, Weie's time in Italy with Zahrtmann was cut short due to a significant disagreement or dispute with his mentor. The exact nature of their conflict remains somewhat obscure, but it was serious enough for Weie to return to Denmark prematurely. This incident perhaps highlights Weie's independent spirit and his unwillingness to compromise his developing artistic convictions.

Upon his return to Denmark, Weie sought out other avenues for artistic growth. He became acquainted with the Swedish painter Karl Isakson, who was also active in the Danish art scene and had studied with Zahrtmann. Isakson, known for his sensitive color harmonies and his deep engagement with the theories of Paul Cézanne, became an important, albeit sometimes contentious, influence on Weie, particularly in the realm of color theory and its application.

The Christiansø Period: A Crucible of Creativity

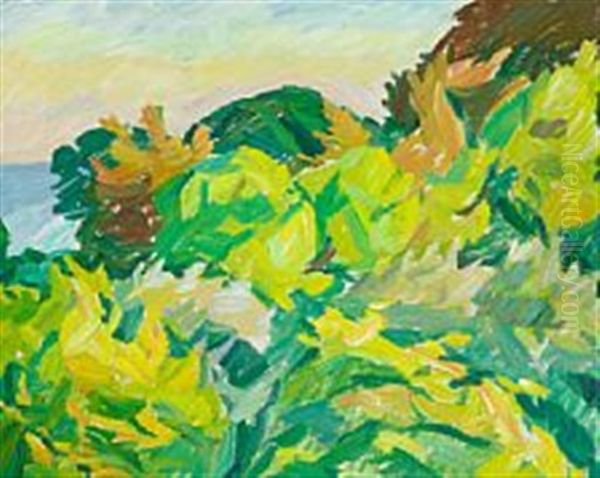

The small, rugged archipelago of Christiansø, located east of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, became a profoundly important place for Edvard Weie. From around 1910 and for roughly the next decade, he spent his summers on Christiansø, finding in its dramatic landscapes, clear light, and relative isolation an ideal environment for artistic exploration. The island's stark beauty, its fishing community, and its historical fortifications provided a rich tapestry of motifs.

It was on Christiansø that Weie's connection with Karl Isakson deepened, at least for a time. They, along with other artists who frequented the island, formed part of what is sometimes loosely referred to as the "Bornholm School" – a group of painters, many of whom were Zahrtmann's former pupils, drawn to the unique atmosphere of Bornholm and its surrounding islands. This group also included notable figures such as Oluf Høst, Olaf Rude, and Kræsten Iversen. While not a formal school with a unified manifesto, these artists shared an interest in modern pictorial problems, particularly concerning color and form, often inspired by French Post-Impressionism.

Weie's paintings from Christiansø are characterized by an increasing boldness in color and a simplification of form. He painted landscapes, seascapes, and scenes of local life, constantly experimenting with how to translate the sensory experience of the island onto canvas. The intense light of the Baltic summers and the raw, elemental nature of the environment pushed him towards a more expressive and less naturalistic mode of representation. Works like Mindet, Christiansø (Memory, Christiansø) capture this deep connection to the place, imbued with both observation and emotional resonance.

Evolution of Style: From Figuration to Abstraction

Edvard Weie's artistic journey was one of continuous evolution and rigorous self-examination. His early works, influenced by the Symbolist tendencies prevalent at the turn of the century and perhaps by Zahrtmann's interest in historical and literary themes, often featured mythological or allegorical subjects. However, as he matured, his focus shifted increasingly towards the direct observation of his surroundings – landscapes, cityscapes (particularly of Copenhagen's harbor), and still lifes.

A key characteristic of Weie's development was his relentless pursuit of what he termed "the picture's own life." This meant moving beyond mere representation to explore the purely formal qualities of painting – color, line, composition, and texture – as expressive means in themselves. He was deeply influenced by the innovations of French modernism, particularly the work of Paul Cézanne, whose emphasis on underlying structure and the construction of form through color planes was revolutionary. The vibrant, non-naturalistic colors of Fauvism, championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, also left a significant mark on Weie's palette.

Throughout the 1910s and into the 1920s, Weie's style became progressively more abstract, though he rarely abandoned figuration entirely. His brushwork grew more vigorous, his colors more intense and often non-local, and his compositions more dynamic and fragmented. He sought to capture not just the appearance of a subject, but its essence, its energy, and the artist's subjective response to it. This quest often involved creating multiple versions of the same motif, constantly reworking and refining his ideas. His still lifes, for example, became laboratories for formal experimentation, where arrangements of everyday objects were transformed into complex orchestrations of color and form.

Key Themes and Motifs

While Weie's style evolved, certain themes and motifs recurred throughout his oeuvre, each providing a vehicle for his artistic investigations. Landscapes, particularly those of Christiansø and the coastal areas around Copenhagen, were a constant source of inspiration. He was fascinated by the interplay of light, water, and land, and he sought to convey the atmospheric conditions and the inherent dynamism of nature. His landscapes are rarely tranquil depictions; instead, they often possess a raw energy and a sense of underlying structure.

Figure compositions, often with mythological or romantic undertones, also occupied a significant place in his work, especially in his earlier and middle periods. These paintings allowed him to explore complex human emotions and narratives, often reinterpreting classical themes through a modern lens. His figures are typically robust and sculptural, integrated into richly colored and textured environments.

Still life painting was another crucial genre for Weie. Like Cézanne before him, Weie used still life as a means to explore fundamental pictorial problems. Objects like fruit, flowers, and household items were arranged and rearranged, providing a controlled setting for his experiments with color relationships, spatial construction, and the material qualities of paint. Works such as Still life with potted plant and oranges demonstrate his ability to imbue simple subjects with extraordinary visual richness and formal complexity.

The urban environment of Copenhagen, especially its harbor, also provided Weie with compelling motifs. His depictions of cityscapes and port scenes capture the bustling activity and the unique light of the Nordic capital, often with a focus on strong compositional lines and a vibrant, almost Fauvist, palette. Udsigt fra Adelmar Odgaards vegne til Børsen (View from Adelmar Odgaard's behalf to the Stock Exchange) is an example of his engagement with the urban landscape.

Masterworks and Their Significance

Several of Edvard Weie's paintings are considered landmarks of Danish modernism. Perhaps his most celebrated work is Nereids and Tritons (Nereider og Tritoner), completed around 1921. This large, dynamic composition depicts mythological sea creatures in a swirling, energetic seascape. The painting is a tour-de-force of color and movement, with figures and waves merging into a vibrant, almost abstract, tapestry. It showcases Weie's mature style, his mastery of complex compositions, and his ability to infuse traditional themes with a modern sensibility. The work is often seen as a culmination of his explorations of color and form, and it holds a prominent place in the collection of the Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery of Denmark).

Another significant work related to this theme is Udkast til Poseidonbilledet (Sketch for the Poseidon Picture), also from around 1921. This piece, likely a study or variant for a larger composition, further illustrates his engagement with mythological subjects and his powerful, expressive use of color to convey drama and energy. The figure of the sea god is rendered with a raw power that borders on the abstract.

Later in his career, Weie continued to produce challenging and innovative works. His 1932 painting, Dante and Virgil in the Underworld, demonstrates his ongoing interest in literary and allegorical themes, reinterpreted through his distinctive modernist lens. This work, with its somber palette and emotionally charged figures, was considered somewhat controversial for its unsettling modern take on a classical subject from Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.

His numerous landscapes from Christiansø, such as En maler ser på motivet. Fra Christiansø (A painter looks at his motif. From Christiansø), are also highly regarded. These works not only capture the specific character of the island but also reflect the artist's intense engagement with the act of painting itself, often depicting the tools of his trade or the artist within the landscape.

Weie the Critic: A Voice of Dissent

Edvard Weie was not only a painter but also a thoughtful and often trenchant art critic. He possessed a sharp intellect and strong convictions about the nature and purpose of art. Throughout his career, he frequently published articles and essays in newspapers and art journals, offering his perspectives on contemporary art, art theory, and the state of the Danish art world.

Weie was often critical of what he perceived as a lack of depth or humanistic value in much of the art being produced by his contemporaries. He championed an art that was both formally innovative and spiritually resonant, an art that could engage the viewer on an intellectual and emotional level. He was wary of art that he felt was merely decorative or superficial. His writings reveal a deep engagement with art history and a desire to see Danish art achieve a level of international significance.

His critical stance sometimes put him at odds with the established art institutions and with fellow artists. He was known for his uncompromising standards and his occasionally polemical tone. This critical engagement, however, was an integral part of his artistic identity. It reflected his profound seriousness about art and his belief in its transformative power. He did not readily join artistic groups or societies, preferring to maintain his independence, though his association with the Bornholm painters was a significant period of collegial interaction. His critical writings, alongside his paintings, contributed to the ongoing discourse about modernism in Denmark.

Relationships and Conflicts

Weie's passionate nature and strong opinions inevitably led to complex relationships and occasional conflicts within the art world. His early break with his teacher, Kristian Zahrtmann, during their trip to Italy, set a precedent for his independent, sometimes oppositional, stance. While Zahrtmann's school provided a crucial foundation, Weie quickly forged his own path.

His relationship with the Swedish painter Karl Isakson was particularly significant. They shared a period of intense artistic dialogue and mutual influence, especially during their time on Christiansø. Isakson's more analytical approach to color, influenced by Cézanne and the Neo-Impressionists, undoubtedly impacted Weie. However, their strong personalities and differing artistic trajectories eventually led to a cooling, and some sources suggest a definitive break or conflict between them. Despite this, Isakson's impact on Weie's development, particularly in his handling of color and his understanding of modernist principles, remains undeniable.

Weie also interacted with other key figures of Danish modernism, such as Harald Giersing and Niels Lergaard. Giersing, like Weie, was a pioneer of modernism in Denmark, known for his bold colors and expressive forms. Lergaard, another painter associated with the Bornholm School, shared Weie's deep connection to landscape. While their individual styles differed, these artists were part of a broader movement that sought to bring Danish art into dialogue with international avant-garde developments. Other contemporaries whose work formed the backdrop to Weie's career include Vilhelm Lundstrøm, known for his Cubist-inspired still lifes and figure paintings, and J.F. Willumsen, an older, highly individualistic figure whose work spanned Symbolism and Expressionism. The broader European context included giants like Edvard Munch, whose expressive power resonated across Scandinavia, and the aforementioned French masters Cézanne, Matisse, and Derain, whose innovations were crucial for modernists everywhere.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Edvard Weie became increasingly self-critical and somewhat reclusive. He was known to rework his canvases extensively, sometimes over many years, and even to destroy works that he felt did not meet his exacting standards. This intense self-scrutiny was a hallmark of his artistic process. He grew disillusioned with what he perceived as the declining quality and humanistic relevance of contemporary art, and he exhibited his work less frequently.

Despite his withdrawal from the public eye, his importance was recognized. In 1925, he was awarded the prestigious Eckersberg Medal, one of Denmark's highest artistic honors. This award acknowledged his significant contributions to Danish art, even as he continued to challenge and provoke.

Edvard Weie passed away in 1943 at the age of 63. His death marked the loss of a unique and powerful voice in Danish art. His legacy, however, has endured and grown over time. He is now widely regarded as one ofthe most important Danish modernist painters, a key figure in the transition from traditional representation to more abstract and expressive forms of art. His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Danish artists who have grappled with similar questions of color, form, and artistic meaning.

His works are prominently featured in major Danish museums, including the Statens Museum for Kunst, and continue to be studied and admired for their intensity, their formal innovation, and their profound emotional depth. Weie's relentless pursuit of artistic truth, his willingness to experiment, and his critical engagement with the art of his time have secured his place as a pivotal and enduring figure in the history of Scandinavian art. His paintings remain a vibrant testament to an artist who dared to see and paint the world anew.

Conclusion

Viggo Thorvald Edvard Weie's contribution to Danish modernism is undeniable and multifaceted. From his challenging beginnings, he forged an artistic path characterized by intense intellectual rigor, profound emotional depth, and an unwavering commitment to the expressive power of color and form. His time on Christiansø was a crucible for his developing style, and his engagement with international modernist currents, particularly French Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, allowed him to create a unique artistic language.

His masterworks, such as Nereids and Tritons, stand as powerful statements of early 20th-century artistic innovation, while his critical writings offer valuable insights into the artistic debates of his era. Though often self-critical and at times at odds with the art establishment, Weie's dedication to his vision and his relentless pursuit of "the picture's own life" resulted in a body of work that continues to inspire and challenge. He remains a vital figure for understanding the complexities and achievements of modern art in Denmark, a painter whose legacy is etched in vibrant color and enduring artistic integrity.