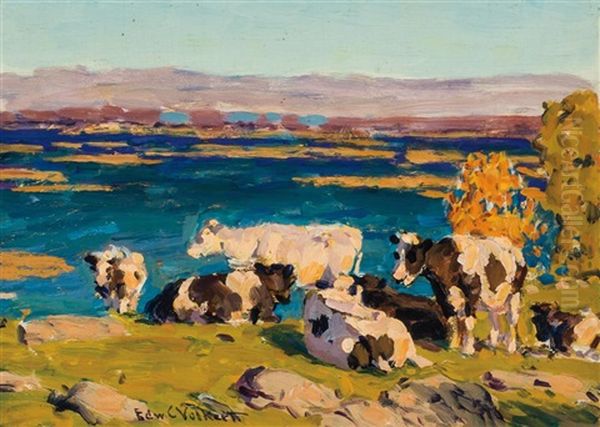

Edward Charles Volkert (1871-1935) stands as a distinctive figure in the landscape of American art, an Impressionist painter whose heart and brush were devoted to capturing the pastoral beauty of rural life, particularly the cattle and agricultural scenes that earned him the affectionate and accurate moniker, "America's Cattle Painter." His work, a harmonious blend of European influences and a uniquely American sensibility, offers a window into a world increasingly receding from modern view, rendered with a keen eye for light, form, and the quiet dignity of his subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on September 19, 1871, Edward Charles Volkert was the son of German and Bavarian immigrants. His father, a merchant from the Alsace-Lorraine region, and his mother, from Bavaria, provided a household that likely valued diligence and craftsmanship. This upbringing in a city with a strong German heritage and a burgeoning arts scene would prove formative for the young Volkert.

His artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious Cincinnati Art Academy, one of the oldest art academies in the United States. Here, he came under the tutelage of Frank Duveneck, a highly influential American figure painter and art educator. Duveneck, known for his robust, direct painting style influenced by the Munich School and masters like Velázquez, instilled in his students a respect for solid draftsmanship and expressive brushwork. Volkert absorbed these lessons, developing a strong technical foundation that would underpin his later Impressionistic explorations. Other notable artists associated with Duveneck and the Cincinnati scene around this period included John Henry Twachtman and Robert Frederick Blum, who, like Volkert, would go on to make significant contributions to American art.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Volkert, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, moved to New York City. He continued his studies at the Art Students League, a progressive institution known for its diverse faculty and student body. He also enrolled at the National Academy of Design, a more traditional bastion of American art. These institutions exposed him to a wider range of artistic philosophies and techniques, including the burgeoning influence of Impressionism, which was then captivating the American art world through the works of artists like Childe Hassam and Theodore Robinson, who had experienced it firsthand in France.

The Development of a Unique Vision: Impressionism and the Rural Ideal

Volkert's artistic style evolved into a distinctive fusion of influences. While he embraced the Impressionist concern for capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, often employing a technique reminiscent of pointillism with small, distinct dabs of color, he never fully abandoned the structural solidity and attention to form instilled by Duveneck. His approach was also informed by the Barbizon School, a mid-19th century French movement that valorized rural landscapes and peasant life, with artists like Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot championing a more direct and unidealized depiction of nature.

Volkert's Impressionism was thus tempered by a commitment to realism, particularly in his depiction of animals. He sought to convey not just the visual impression of a scene but also its underlying truth. This dedication led him to an unusual, yet telling, practice: he frequently visited slaughterhouses to study bovine anatomy. This meticulous research enabled him to render cattle with an accuracy and understanding that few artists could match, capturing their musculature, movement, and even their individual character.

His subject matter became increasingly focused on the agrarian world. He painted cattle grazing in sun-dappled pastures, oxen patiently hauling logs or plowing fields, and farmers engaged in their daily toil. These were not romanticized, idyllic visions in the vein of some earlier pastoral painters, but rather honest, empathetic portrayals of a way of life he deeply respected. His landscapes often featured the rolling hills and farmlands of Ohio and, later, Connecticut, depicted with a vibrant palette and a sensitivity to the changing seasons.

The Old Lyme Art Colony: A Confluence of Impressionist Talent

A significant chapter in Volkert's life and career unfolded in Old Lyme, Connecticut. This picturesque town became a major center for American Impressionism, often referred to as the "American Giverny," centered around the boardinghouse of Florence Griswold. Miss Florence, as she was affectionately known, opened her home to artists, creating a supportive and stimulating environment that attracted some of the leading figures of American Impressionism.

Volkert became a regular visitor and eventually a resident of the Florence Griswold House. Here, he was in the company of artists such as Childe Hassam, perhaps the most famous American Impressionist, known for his vibrant depictions of cityscapes, coastal scenes, and New England gardens. Willard Metcalf, another prominent member, was celebrated for his lyrical and atmospheric New England landscapes. Other key figures who frequented Old Lyme and contributed to its artistic vibrancy included Henry Ward Ranger, often considered one of the colony's founders, whose Tonalist style gradually gave way to the brighter palettes of Impressionism; Frank Vincent DuMond, an influential teacher as well as painter; Wilson Irvine, known for his innovative techniques and prismatic palette; and Walter Griffin, who brought a rugged, expressive quality to his landscapes.

The Old Lyme Art Colony provided Volkert with camaraderie, intellectual exchange, and an environment deeply attuned to the principles of plein air painting. He participated actively in the Lyme Art Association, which was formed by the artists of the colony to exhibit and promote their work. His presence there further solidified his reputation as a significant contributor to the American Impressionist movement. Artists like Lewis Cohen, William Chadwick, Matilda Browne (one of the few women to achieve prominence in the colony, also known for her animal paintings), Bruce Crane, Allen Butler Talcott, and Clark Voorhees were also part of this dynamic artistic community, each contributing to the rich tapestry of styles and subjects that characterized Old Lyme.

Mature Career, Recognition, and Artistic Process

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Volkert's work gained increasing recognition. He exhibited widely, and his paintings were featured in prestigious venues such as the galleries of the New York Watercolor Club and the National Academy of Design, where he was elected an Associate Member (ANA) in 1917 and a full National Academician (NA) in 1921. He also served as President of the Bronx Society of Arts and Sciences, demonstrating his commitment to the broader artistic community.

His reputation as "America's Cattle Painter" solidified, particularly in the 1920s, as his depictions of cattle garnered critical acclaim for their anatomical accuracy, sympathetic portrayal, and masterful handling of light. Volkert's dedication to his primary subject was profound. He was known to spend countless hours observing cattle in their natural environment, sketching them from life, and meticulously studying their forms.

A fascinating aspect of Volkert's artistic practice was his creation of a "Cattle Log." This was a series of small, meticulously painted replicas of his larger works, primarily those featuring cattle. The purpose of this log was twofold: it served as a personal record of his output, and it also provided a reference from which he could potentially recreate a painting if the original was lost or damaged. This practice underscores his methodical approach and his deep investment in his chosen subject matter.

His preferred media were oil and watercolor, and he handled both with considerable skill. His oils often featured rich impasto and vibrant color, capturing the textures of the landscape and the solidity of his animal subjects. His watercolors were characterized by a more fluid, luminous quality, well-suited to capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere.

Personal Life: Triumphs and Tragedies

Volkert's personal life, like that of many artists, had its share of challenges that inevitably influenced his work. An early marriage ended in divorce, a painful experience that reportedly led to the loss of contact with his two children from that union. It has been suggested by some art historians that this personal sorrow may have deepened his connection to the natural world and the steadfast, uncomplicated presence of the animals he painted, finding solace and a sense of order in the rhythms of rural life. His landscapes from this period often convey a profound love for nature and a reverence for the unspoiled countryside, perhaps as a counterpoint to personal turmoil.

Later in life, he found companionship and stability. However, tragedy struck again in 1933 with the premature death of his daughter. This profound loss reportedly had a devastating impact on Volkert, diminishing his creative drive in his final years.

A significant aspect of Volkert's later life was his adherence to Christian Science. This faith, founded by Mary Baker Eddy, emphasizes spiritual healing and often involves a rejection of conventional medical treatment. This belief would play a role in the circumstances surrounding his death.

Representative Works

While a comprehensive catalogue of Volkert's oeuvre is extensive, several works stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

_The Farm_: This title, likely applied to several works depicting farm scenes, encapsulates his core subject. Paintings under this or similar titles would typically feature pastoral landscapes, often with cattle grazing or farm buildings nestled in the countryside, all rendered with his characteristic attention to light and atmospheric effect. One such painting titled The Farm was auctioned at Cowan's Auctions, showcasing a serene rural scene.

_Untitled (Oxen Hauling Logs in the Snow)_: This work, held in the collection of the Florence Griswold Museum, is a powerful example of Volkert's ability to capture the labor of animals in a challenging environment. The depiction of oxen straining against the weight of logs in a snowy landscape would highlight his skill in rendering animal anatomy, the texture of snow, and the cool, diffused light of a winter's day.

_Farmers Ferry_: This was a large-scale mural painted by Volkert for the Western High School in Connecticut. Murals were a significant form of public art during this period, often commissioned to depict scenes of local history or industry. A work like Farmers Ferry would have allowed Volkert to engage with a narrative subject on a grand scale, likely showcasing his skills in composition and his understanding of rural life and its historical aspects.

His body of work consistently demonstrates a deep empathy for his subjects, whether they are the gentle cattle, the hardworking oxen, or the enduring landscapes they inhabit. He captured the interplay of light on an animal's hide, the dappled shadows under a summer tree, or the crisp air of an autumn morning with equal facility.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

The death of his daughter in 1933 cast a shadow over Volkert's final years. His creative output reportedly waned as he grappled with this loss. In 1935, Edward Charles Volkert fell ill with uremia, a serious kidney condition. Consistent with his Christian Scientist beliefs, he declined conventional medical treatment. He passed away on March 4, 1935, in Old Lyme, Connecticut, the town that had become his artistic home.

Despite the personal tragedies and the perhaps quieter fame compared to some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, Edward Charles Volkert left an indelible mark on American art. He was a dedicated and skilled painter who carved out a unique niche with his focus on cattle and agrarian life. His work provides a valuable record of a rapidly changing American landscape, capturing the dignity of agricultural labor and the beauty of the rural environment.

His paintings are held in the collections of numerous museums and institutions, including the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, which has a significant holding of his work and has organized exhibitions such as "Hauling and Harrowing: Edward Volkert and the Connecticut Farm." His works also appear in the Milwaukee Art Museum, and he is represented in the archives and collections associated with the National Academy of Design and the Lyme Art Association. Other institutions with connections to the Lyme Art Colony and American Impressionism, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, university collections at Harvard and Princeton, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the New York Public Library, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (formerly the National Museum of American Art), help contextualize his contributions within the broader scope of American art history.

His auction records, with works appearing at houses like Cowan's Fine and Decorative Art and John Moran Auctioneers, attest to a continued appreciation for his art among collectors. He remains a respected figure among scholars of American Impressionism, valued for his technical skill, his unique subject matter, and his sincere, unpretentious vision.

Edward Charles Volkert's legacy is that of an artist who remained true to his vision, finding profound beauty and meaning in the everyday scenes of the American countryside. He was more than just "America's Cattle Painter"; he was a sensitive observer of light, a skilled draftsman, and a heartfelt chronicler of a way of life that continues to resonate through his enduring canvases. His work invites us to pause and appreciate the quiet strength and pastoral charm of the world he so lovingly depicted, a world shaped by the enduring partnership between humans, animals, and the land.