Edward Stott (1859-1918) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late Victorian and Edwardian British art. Revered in his time as the "poet-painter of the twilight," Stott carved a unique niche for himself with his evocative and atmospheric depictions of rural life, domestic scenes, and biblical narratives, all imbued with a characteristic sensitivity to light and mood. His work, deeply influenced by his studies in Paris and his profound connection to the English countryside, offers a gentle, pastoral vision that continues to resonate with viewers today.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Rochdale, Lancashire, in 1859 (some earlier sources incorrectly state 1855 or 1857, but 1859 is now widely accepted), Edward Stott was the son of a prosperous cotton mill owner. His early life was spent amidst the industrial heartland of England, a stark contrast to the bucolic scenes he would later become famous for painting. Despite his family's business background, Stott harbored artistic ambitions from a young age. He initially worked in his father's office in Manchester for five years, a period during which he likely attended evening classes at the Manchester School of Art, nurturing his nascent talent.

His formal artistic training, however, truly began when he made the pivotal decision to move to Paris in 1880. This was a common path for aspiring artists of his generation, seeking the advanced instruction and vibrant artistic environment that the French capital offered, which was then considered the epicenter of the art world. This move marked a definitive break from a commercial career and a full commitment to the life of an artist.

Parisian Training and Influences

In Paris, Stott enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied under the tutelage of renowned academic painter Alexandre Cabanel. Cabanel, a master of the academic tradition, would have instilled in Stott a strong foundation in drawing and composition. However, Stott also sought out other influences, notably spending time in the atelier of Charles Auguste Émile Durand, known as Carolus-Duran. Carolus-Duran, himself a teacher of John Singer Sargent, encouraged a more direct and painterly approach, emphasizing the importance of capturing the immediate visual impression.

Beyond the formal ateliers, Stott was profoundly affected by the prevailing artistic currents in Paris. He was particularly drawn to the work of the French Realists and Naturalists, artists who depicted everyday life and rural labor with honesty and dignity. The influence of Jean-François Millet, with his solemn and monumental portrayals of peasant life, is palpable in Stott's later work. Similarly, Jules Bastien-Lepage, who combined academic technique with a plein-air sensibility to create highly detailed and emotionally resonant rural scenes, left an indelible mark on Stott's artistic vision. The Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, with their poetic landscapes and subtle tonal harmonies, also likely contributed to his developing aesthetic.

Stott absorbed the Impressionists' fascination with light and atmosphere, though he never fully adopted their broken brushwork or scientific approach to color. Instead, he synthesized these influences into a more personal style, characterized by a muted palette, soft forms, and a focus on the crepuscular hours – dawn and, more frequently, dusk. This period in Paris was crucial in shaping his artistic identity, providing him with technical skills and exposing him to the ideas that would underpin his mature work.

Return to England and the New English Art Club

After his formative years in Paris, Stott returned to England around 1883. He brought with him a continental sensibility that set him apart from some of the more traditional factions of the British art scene. He became associated with a group of like-minded artists who were also looking to France for inspiration and seeking to challenge the perceived conservatism of the Royal Academy.

Stott was a founding member of the New English Art Club (NEAC), established in 1886. The NEAC provided a vital platform for artists influenced by French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, offering an alternative exhibition venue to the Royal Academy. Its members included prominent figures such as Philip Wilson Steer, Walter Sickert, George Clausen, and Frank Bramley. Clausen and Bramley, like Stott, were particularly interested in rural naturalism and the depiction of agricultural life, often drawing comparisons to the Newlyn School painters like Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley, who were similarly capturing the realities of rural and coastal communities.

Stott's involvement with the NEAC placed him at the forefront of progressive art in Britain. While his work was perhaps less radical than that of Sickert or Steer, his commitment to capturing natural light and atmosphere, and his focus on everyday subjects, aligned perfectly with the club's ethos. He exhibited regularly with the NEAC, as well as at the Royal Academy, where he was elected an Associate (ARA) in 1906, indicating a growing acceptance of his style within the establishment.

Amberley: The Muse of Sussex

A defining moment in Stott's life and career was his decision to settle in the picturesque village of Amberley, nestled in the South Downs of West Sussex, around 1889. He would remain there for the rest of his life, and the surrounding landscape and its inhabitants became the primary subjects of his art. Amberley, with its rolling hills, thatched cottages, and tranquil Arun River, provided the perfect backdrop for his pastoral idylls.

Stott became deeply integrated into the village community. He was not merely an observer but an active participant in local life. This immersion allowed him to depict his subjects with an intimacy and authenticity that might have eluded a more detached artist. He developed a profound love for the area and was a keen advocate for its preservation, particularly campaigning for the upkeep of its traditional thatched-roof cottages, which feature prominently in many of his paintings. His dedication to the local environment extended to his daily habits; he was known for his long walks, often covering eight miles a day through the Sussex countryside, constantly observing and sketching.

The peace and rustic charm of Amberley were essential to Stott's artistic temperament. It was here that he truly became the "poet-painter of the twilight," capturing the fleeting moments of beauty in the changing light, the quiet dignity of rural labor, and the tender interactions of family life. His home and studio in Amberley became his sanctuary and his primary source of inspiration.

Thematic Focus: Rural Life, Domesticity, and Biblical Scenes

Edward Stott's oeuvre is characterized by a consistent focus on a few key themes, all rendered with his signature atmospheric touch.

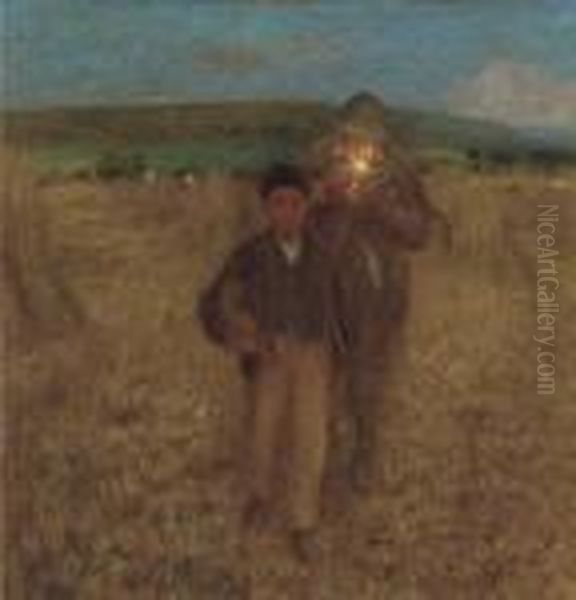

Rural Life: The agricultural landscape and its workers are central to Stott's art. He painted scenes of ploughing, harvesting, sheep-herding, and other rural activities. Works like The Harvesters' Return or The Old Gate depict laborers at the end of a long day, often silhouetted against a glowing twilight sky. These are not grand, heroic portrayals, but quiet, contemplative moments that emphasize the harmony between humanity and nature. His depictions of animals, such as in Study of Goats or Folding Time, are rendered with a similar sensitivity and understanding.

Domesticity and Childhood: Stott also excelled at capturing intimate domestic scenes, often featuring women and children. Paintings like Boy at Breakfast (1901), At the Bedside (1890s), or Motherhood convey a sense of warmth, tenderness, and quietude. He had a particular ability to portray the innocence and vulnerability of childhood, often set within simple cottage interiors or peaceful garden settings. These works are imbued with a gentle sentimentality, but avoid becoming overly saccharine due to the sincerity of his observation.

Biblical and Pastoral Idylls: Later in his career, Stott increasingly turned to biblical themes, but he interpreted them through the lens of his rural experience. His religious paintings are not set in an imagined Holy Land, but in the familiar Sussex landscape. Shepherds become Sussex shepherds, and holy families resemble the local villagers. Works such as The Good Samaritan or The Flight into Egypt are transpositions of sacred stories into a contemporary pastoral setting, making them feel both timeless and immediate. These paintings often possess a mystical quality, enhanced by his masterful use of twilight or moonlight.

Artistic Technique: Light, Atmosphere, and Mediums

The most distinctive feature of Edward Stott's art is his profound understanding and depiction of light, particularly the soft, diffused light of dawn and dusk. He was less interested in the bright, analytical light of midday favored by many Impressionists, and more drawn to the transitional moments when forms soften, colors become muted, and a sense of mystery pervades the landscape. His palette often consisted of subtle greys, blues, mauves, and soft yellows, creating a harmonious and poetic effect.

Stott's working method typically involved making numerous preparatory sketches outdoors. He would use pencil, charcoal, and watercolors to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere directly from nature. These sketches, often small and rapidly executed, served as aides-mémoires. He would then return to his studio to develop these initial impressions into finished oil paintings. This combination of direct observation and studio refinement allowed him to balance spontaneity with careful composition and tonal control.

While proficient in oils, Stott was also a master of pastels. This medium, with its soft, powdery texture, was perfectly suited to his atmospheric style. Pastels allowed him to achieve a unique luminosity and a subtle blending of tones that enhanced the dreamlike quality of many of his works. His pastel drawings are often highly finished and stand as significant works in their own right. His handling of paint was often delicate, with layers of pigment applied to create a sense of depth and vibration, rather than the impasto techniques of some of his contemporaries.

Key Works Explored

Several paintings stand out as representative of Edward Stott's artistic achievements:

The Widow's Acre (1900): This poignant work depicts a solitary female figure working a small patch of land, likely her only means of subsistence. The mood is one of quiet resilience, set against a vast, atmospheric sky. It showcases Stott's ability to convey deep emotion through subtle means and his empathy for the rural poor.

Boy at Breakfast (1901): A charming interior scene, this painting captures a quiet moment of domestic life. The light filtering through a window illuminates a young boy at a simple table. The work is notable for its gentle observation and its harmonious color scheme, typical of Stott's domestic pieces.

The Harvesters' Return: This painting, or variations on this theme, captures a common motif in Stott's work – laborers returning home at dusk. The figures are often silhouetted against a luminous sky, emphasizing the end of a day's toil and the transition to rest. It speaks to the rhythm of rural life and the dignity of labor.

Sunday Morning: This work likely depicts a family or villagers, perhaps on their way to or from church, enjoying a moment of peaceful congregation. It reflects the quiet social fabric of village life, a theme Stott often returned to.

Folding Time (or The Fold Yard): Scenes of sheep being gathered into a fold at twilight are recurrent in Stott's oeuvre. These paintings are masterpieces of atmospheric effect, with the soft wool of the sheep catching the fading light and the landscape dissolving into shadow. They evoke a sense of peace and timeless pastoral tradition.

These works, among many others, demonstrate Stott's consistent vision and his mastery of his chosen themes and techniques.

Personal Life, Character, and Anecdotes

Edward Stott was described by those who knew him as a somewhat reserved and solitary figure, deeply committed to his art. His decision to live in Amberley, away from the bustling London art scene, reflects a preference for a quieter, more contemplative existence. His daily eight-mile walks were not just for exercise but were integral to his artistic practice, a way of immersing himself in the landscape he loved.

There are charming anecdotes about his character. He was reportedly fond of old, comfortable clothes, sometimes appearing rather shabby, which perhaps spoke to his unpretentious nature and his focus on inner rather than outer concerns. He also had an interest in health foods, which might have been unusual for the time.

An interesting point of potential confusion arises with another artist of the same period, William Stott of Oldham (1857-1900). William Stott was also a significant painter, known for his association with the plein-air movement and his connections to artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage. To avoid confusion, William Stott often signed his works "William Stott of Oldham." While their paths and influences might have overlapped to some extent, Edward Stott of Amberley developed his own distinct "twilight" aesthetic.

Relationships with Contemporaries

As a member of the NEAC, Edward Stott was part of a circle of progressive artists. He would have known and interacted with figures like George Clausen, whose rural naturalism shared affinities with Stott's own, though Clausen's work often had a stronger social realist edge. He would also have been acquainted with Philip Wilson Steer, whose Impressionistic landscapes, though often brighter and more overtly French in style, shared a commitment to capturing atmospheric effects. Walter Sickert, another prominent NEAC member, pursued a grittier, urban realism, offering a contrast to Stott's pastoralism.

His relationship with James McNeill Whistler, a towering figure in the late Victorian art world, is less clearly documented in terms of direct collaboration, but Stott would undoubtedly have been aware of Whistler's "Nocturnes" and his emphasis on "art for art's sake." Whistler's tonal harmonies and atmospheric cityscapes, though different in subject, shared a certain poetic sensibility with Stott's twilight scenes. Both artists prioritized mood and aesthetic effect over literal representation.

While Stott was respected by his peers, his somewhat reclusive nature and his focus on a specific, personal vision meant he was perhaps less involved in the cut-and-thrust of artistic politics than some of his contemporaries. His art speaks more of a quiet dialogue with nature and the human spirit than of engagement with radical artistic manifestos.

Critical Reception, Legacy, and Art Historical Evaluation

During his lifetime, Edward Stott achieved considerable recognition. His election as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1906 was a significant honor. His work was regularly exhibited and generally well-received by critics who appreciated his poetic sensibility and his technical skill, particularly his handling of light. He was seen as an artist who successfully blended French influences with a distinctly English pastoral tradition.

However, like many artists whose styles fall between major, easily classifiable movements, Stott's reputation experienced a period of relative neglect in the decades following his death in 1918. The rise of Modernism, with its emphasis on abstraction and radical formal innovation, tended to overshadow more traditional or representational artists. The pastoral themes that were so popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries fell somewhat out of fashion.

In more recent times, there has been a renewed appreciation for artists of Stott's generation who offered a more nuanced engagement with Impressionism and Naturalism. Retrospectives and scholarly attention have helped to re-evaluate his contribution. For instance, the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne, which holds a significant collection of his work, has played a role in bringing his art to a wider audience.

Art historically, Stott is valued for his unique interpretation of rural themes. He avoided the overt social commentary of some realists and the purely optical concerns of some Impressionists. Instead, he forged a deeply personal style that was both romantic and naturalistic. His "twilight" paintings are particularly esteemed for their lyrical beauty and their technical mastery. While he may not have been a revolutionary innovator in the mold of Picasso or Matisse, his work represents a significant strand of British art at the turn of the 20th century, offering a vision of enduring appeal.

There were, of course, minor controversies or criticisms. Some might have found his subject matter too sentimental or his focus on atmosphere occasionally leading to a lack of formal rigor in comparison to more avant-garde artists. The very subtlety of his light effects could also be a challenge; reports from exhibitions sometimes noted that his works needed careful lighting to be fully appreciated, as their delicate tonal gradations could be lost in poorly lit galleries.

Stott's Enduring Place in Art History

Edward Stott's contribution to British art lies in his ability to capture the soul of the English countryside and its people with a profound sensitivity and poetic grace. He was a bridge between the academic traditions of the 19th century and the newer currents of Impressionism and Naturalism, forging a style that was uniquely his own. His dedication to the depiction of twilight and its associated moods created a body of work that is both visually beautiful and emotionally resonant.

He stands alongside other British artists who found inspiration in rural life, such as George Vicat Cole with his expansive landscapes, or Benjamin Williams Leader, whose popular scenes often depicted the sunnier aspects of the countryside. Stott's vision, however, was more intimate and introspective. He was a contemporary of artists like John William Waterhouse, who explored mythological and romantic themes, and Sir Alfred Munnings, who would later become famous for his equestrian art. Within this diverse artistic landscape, Stott's quiet pastoralism holds a special place.

His legacy is that of an artist who remained true to his personal vision, creating a world of gentle beauty and quiet contemplation. In an era of rapid industrialization and social change, Stott's paintings offered a vision of timeless rural harmony, a "poetry of the earth" that continues to captivate and console.

Conclusion

Edward Stott of Amberley, the "poet-painter of the twilight," was more than just a skilled landscapist or a painter of rustic scenes. He was an artist who imbued his subjects with a deep sense of feeling and a profound appreciation for the subtleties of the natural world. His life spent in Amberley, observing and translating its gentle rhythms into paint, resulted in a body of work that is both a valuable record of a bygone era and a timeless evocation of pastoral beauty. His paintings invite us to pause, to observe the quiet moments, and to find beauty in the everyday, particularly in those magical, transitional hours when the world is bathed in the soft glow of fading light. His art remains a testament to a gentle spirit and a singular artistic vision.