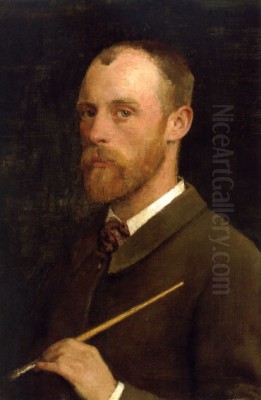

Sir George Clausen stands as a significant figure in British art, bridging the late Victorian era and the early stirrings of modernism in the 20th century. Born in London on April 18, 1852, he died in Cold Ash, Berkshire, on November 22, 1944, leaving behind a rich legacy of paintings, drawings, and prints. Primarily celebrated for his depictions of rural life and labour, Clausen masterfully captured the effects of light, particularly sunlight, on the English landscape and its inhabitants. His career reflects a fascinating journey through the artistic currents of his time, absorbing influences from French Naturalism and Impressionism while forging a distinctly personal and British style. He was not only a prolific artist but also an influential teacher and a respected member of the art establishment, eventually receiving a knighthood for his contributions.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

George Clausen's artistic inclinations were perhaps nurtured early on. His father, George Clausen Sr., was an immigrant decorative artist of Danish descent, suggesting a household where visual arts were appreciated. The young Clausen's formal training began in London at the South Kensington Schools (now the Royal College of Art) from 1867 to 1873. These schools provided a solid grounding in drawing and design, typical of the rigorous academic training of the period.

Following his time at South Kensington, Clausen gained practical experience working in the studio of Edwin Long RA (1829-1891). Long was a successful painter known for his historical and biblical scenes, often with an Orientalist flavour. Working under an established Royal Academician would have provided Clausen with insights into professional practice, technique, and the workings of the London art world, particularly the Royal Academy of Arts, which dominated the scene.

Seeking broader horizons and exposure to continental trends, Clausen, like many ambitious artists of his generation, travelled to Paris. This was a pivotal step. He studied further under leading academic figures: William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) at the Académie Julian and Tony Robert-Fleury (1837-1911). Bouguereau, in particular, was renowned for his highly finished, idealized nudes and peasant scenes, representing the pinnacle of French academic tradition. While Clausen would ultimately move away from this polished style, the rigorous drawing and compositional skills honed under these masters provided a crucial foundation.

The Lure of France: Naturalism and Impressionism

Paris in the late 1870s and early 1880s was a crucible of artistic innovation. While Clausen studied under academic masters, he was inevitably exposed to more radical movements. The most profound influence came not from the high academics but from the proponents of Naturalism and Impressionism. Chief among these influences was the French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884).

Bastien-Lepage championed a form of Naturalism that combined meticulous, almost photographic detail in the foreground figures with a more atmospheric, tonally subtle rendering of the background landscape. He often depicted peasants with an unsentimental realism and dignity, working directly from life outdoors (plein air). This approach deeply resonated with Clausen and many other British artists who saw it as a truthful and modern way to depict contemporary rural life, moving away from the often anecdotal or overly sentimentalized scenes popular in Victorian Britain. Clausen adopted aspects of Bastien-Lepage's technique, including the use of a square brushstroke and a palette often favouring cooler, greyed tones, especially for outdoor light.

Beyond Bastien-Lepage, the broader influence of French art was significant. The Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), known for his solemn portrayals of peasant labour like The Gleaners, provided a precedent for elevating rural themes. Clausen admired Millet's gravitas and empathy. Furthermore, the Impressionists, including Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), with their revolutionary focus on capturing fleeting effects of light and colour using broken brushwork, also impacted Clausen's developing style, particularly his handling of sunlight and atmosphere, although he rarely dissolved form to the extent of the French Impressionists.

Forging an English Style: Rural Life and Labour

Returning to England, Clausen settled first in London and later moved to the countryside, living for periods in Hertfordshire and Essex. This immersion in rural England became central to his art. He dedicated himself to observing and painting the lives of farm labourers, their families, and the landscapes they inhabited. His work stood out for its authenticity and empathy, avoiding condescension or excessive romanticization.

His subjects were the everyday tasks and moments of rural existence: ploughing, sowing, harvesting, resting. Works like Winter Work (1883-84) show men hedging and ditching under a cold sky, rendered with a sober realism influenced by Bastien-Lepage. The Stone Pickers (1887) depicts the back-breaking labour of women and children clearing fields, highlighting the harsh realities alongside the picturesque potential of the countryside.

One of his most celebrated early works, The Girl at the Gate (1889, Tate), exemplifies his mature style of this period. It shows a young country girl standing by a gate, bathed in the soft light of late afternoon. The figure is rendered with considerable solidity and detail, yet the surrounding foliage and background are treated more loosely, capturing the atmospheric quality of the light. The painting combines careful observation with a poetic sensibility, showcasing his ability to blend Naturalistic detail with an Impressionistic concern for light. Another notable work, Schoolgirls (1880, Yale Center for British Art), also known as High School, Hampstead, shows his interest in contemporary life even before fully dedicating himself to rural themes.

Mastery of Light and Atmosphere

A defining characteristic of Clausen's art throughout his career was his fascination with and mastery of light. He explored light in all its variations: the brilliant glare of midday sun, the dappled light filtering through trees, the soft glow of dawn and dusk, the cool light of a winter's day, and the warm, enclosed atmosphere of barns and interiors lit by lanterns or shafts of sunlight.

Unlike the purely objective approach of some Impressionists, Clausen often used light to evoke mood and emotion. His paintings frequently feature figures silhouetted against a bright sky or bathed in a luminous haze, lending them a sense of universality or quiet dignity. Works such as Sunrise in Winter capture the specific atmospheric conditions of the English climate with remarkable fidelity.

His interior scenes, like Interior of an Old Barn or The Farmer's Boy, demonstrate his skill in handling complex light sources. He captured the way sunlight streams through doorways or cracks in the walls, illuminating dust motes in the air and casting deep shadows, creating spaces that feel both tangible and evocative. This sensitivity to light effects became increasingly pronounced in his later work, where his brushwork often became looser and his palette brighter, moving closer to a more purely Impressionistic rendering of visual sensation.

The New English Art Club and the Royal Academy

Clausen navigated the complex London art world by engaging with both its established institutions and its more progressive elements. In 1886, he became a founder member of the New English Art Club (NEAC). The NEAC was established by artists who felt frustrated by the perceived conservatism of the Royal Academy's exhibitions. It provided a platform for artists influenced by French plein air painting, Naturalism, and Impressionism. Fellow founders and early members included Philip Wilson Steer (1860-1942), Frederick Brown (1851-1941), and Walter Sickert (1860-1942), though Sickert's urban realism differed significantly from Clausen's rural focus. John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), though primarily a portraitist, also exhibited with the NEAC and shared an interest in capturing light effects.

Despite his involvement with the NEAC, Clausen did not entirely reject the establishment. He continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) and sought recognition within its ranks. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1895 and became a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1906. This dual affiliation reflects his position as something of a bridge figure – respected by the avant-garde for his modern techniques and subject matter, yet skilled and diplomatic enough to gain acceptance within the traditional bastion of the RA.

His standing within the Academy was further solidified when he was appointed Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy Schools in 1904, a position he held until 1906. His lectures, later published as "Six Lectures on Painting" (1904) and "Aims and Ideals in Art" (1906), were influential. In them, he advocated direct observation of nature, sincerity of expression, and the importance of light and atmosphere, effectively promoting aspects of Impressionist and Naturalist theory within the Academy's own walls. He encouraged students to look closely at the work of artists like Degas (1834-1917) and Whistler (1834-1903), alongside older masters. His teaching influenced a generation of students, and his ideas resonated beyond Britain, notably impacting some Australian artists.

War Artist and Later Works

The outbreak of the First World War brought a temporary shift in Clausen's focus. Like many artists, he contributed to the war effort through his work. He was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee. One of his most poignant works from this period is Youth Mourning (1916, Imperial War Museum), a deeply felt allegorical painting depicting a grieving young woman in a desolate, war-torn landscape, symbolizing the losses endured by a generation.

He also produced images of industrial labour related to the war, such as Gun Factory at Woolwich Arsenal (1918), capturing the intense activity and scale of munitions production. These works demonstrate his versatility and his ability to apply his observational skills and mastery of light to different, more challenging subjects. However, after the war, he largely returned to his preferred themes of landscape and rural life.

In his later career, Clausen's style continued to evolve. His handling often became broader and more simplified, focusing increasingly on pure effects of light and atmosphere. Landscapes sometimes took precedence over figures, and his palette could become even brighter and more vibrant. He continued to paint and exhibit actively into old age. His long and distinguished career was recognized with a knighthood in 1927. He remained a respected elder statesman of British art until his death in 1944 at the age of 92.

Technique and Media

Clausen was a versatile artist, proficient in several media. While best known for his oil paintings, he was also an accomplished watercolourist and pastellist. His watercolours often possess a freshness and immediacy, effectively capturing transient light effects. Pastels allowed him to explore colour and tone with a different texture and vibrancy.

He was also a skilled printmaker, producing etchings and mezzotints. These often revisited themes from his paintings, allowing him to explore compositional and tonal possibilities in a different medium. His etchings, in particular, show a fine control of line and shadow.

His oil painting technique varied throughout his career. In his earlier Naturalist phase, influenced by Bastien-Lepage, he often employed relatively smooth surfaces with detailed rendering in key areas, combined with more atmospheric backgrounds. Later, particularly when depicting strong sunlight, his brushwork became looser, more broken, and textured, reflecting Impressionist influence. He was consistently concerned with accurately representing tonal values – the relative lightness or darkness of colours – which gives his paintings their convincing sense of light and form.

Contemporaries and Context

Clausen's career unfolded during a period of significant change in British art. He worked alongside artists associated with various movements. His connection to the NEAC placed him alongside figures like Steer and Brown, who were similarly exploring French-influenced landscape painting. His rural subjects paralleled those of the Newlyn School painters in Cornwall, such as Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) and Frank Bramley (1857-1915), although the Newlyn artists often favoured a cooler, greyer light compared to Clausen's frequent exploration of bright sunlight.

Within the Royal Academy, he was a contemporary of figures representing the late Victorian establishment, such as the Classicist President Sir Edward Poynter (1836-1919) and narrative painters like Luke Fildes (1843-1927). While respected within the RA, Clausen's work, with its modern French influences, offered a different path from the highly finished historical or anecdotal pictures favoured by some older Academicians like Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) or the earlier generation of Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais (1829-1896), whose detailed realism was of a different nature. Clausen represented a progressive force within the institution, advocating for observational truth and the importance of light.

His market success, indicated by anecdotes like the high price achieved for A Village Boy (£12,000 in 1899, a substantial sum then), shows he achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, competing effectively in the art market of the day.

Legacy and Reputation

Sir George Clausen holds a secure place in the history of British art as a leading painter of rural life and a master interpreter of light. He successfully synthesized influences from French Naturalism and Impressionism into a personal style that resonated with British sensibilities. His work provides a valuable record of English agricultural life during a period of social and economic change, rendered with empathy and keen observation.

He played a significant role as an educator, influencing students through his teaching at the Royal Academy Schools and his published lectures. His advocacy for direct observation and the study of light helped modernize academic training in Britain. As a founder member of the NEAC and a respected RA, he bridged the gap between progressive art circles and the established institutions.

While perhaps overshadowed in the mid-20th century by the rise of abstraction and more radical forms of modernism, Clausen's reputation has steadily endured and arguably grown in recent decades. His works are held in major public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Imperial War Museum, and numerous regional galleries in the UK and abroad. The enduring appeal of his paintings lies in their technical skill, their sensitive portrayal of human labour and the natural world, and above all, their luminous celebration of light. He remains a key figure for understanding the transition in British art from the 19th to the 20th century.