The tradition of British sporting art is rich and varied, capturing the pursuits and passions of a nation deeply connected to the countryside, its animals, and its pastimes. Within this celebrated genre, numerous artists dedicated their talents to depicting the thrill of the hunt, the elegance of thoroughbred horses, and the loyal companionship of dogs. Among these was Edwin Loder of Bath, an artist who, while perhaps not as universally renowned as some of his contemporaries, contributed to the visual record of nineteenth-century sporting life, following in a significant familial artistic tradition.

A Heritage of Artistry: The Loder Family

Edwin Loder (c. 1827 – 1908) was born into an artistic milieu in the historic city of Bath, a place known not only for its Roman baths and Georgian architecture but also as a hub for artists and society. His primary artistic influence and connection was his father, James Loder (c. 1784–1860), himself a respected painter of animals and sporting scenes. James Loder, also known as J. Loder of Bath, established a reputation for his proficient portrayals of horses and dogs, often commissioned by local gentry and sporting enthusiasts.

James Loder's career provided the foundational environment for Edwin's development. The elder Loder was active from the early 19th century, and his works are characterized by a competent, if sometimes somewhat naive, depiction of animal anatomy and a clear, straightforward narrative style. He painted racehorses, hunters, and beloved canine companions, contributing to the strong regional demand for such pictures. It was from his father's studio and under his tutelage that Edwin Loder honed his skills and eventually took on commissions, continuing the family's specialization.

This familial line of artistic practice was not uncommon in British art history. One might think of the Nasmyth family of landscape painters in Scotland, or the various members of the Herring family, particularly John Frederick Herring Sr., who also saw his sons follow him into the realm of animal and sporting painting. This continuation of a specific genre within a family often ensured a steady stream of patronage and a deep, ingrained understanding of the subject matter.

Edwin Loder's Artistic Focus and Style

Edwin Loder's professional life was centered in Bath, where he operated, at least initially, from his father's established studio. He specialized, much like James, in animal and sporting subjects. His oeuvre included portraits of hounds, gundogs, terriers, horses, and occasionally livestock. These commissions would have come from landowners, masters of hunts, and proud pet owners eager to have their prized animals immortalized on canvas.

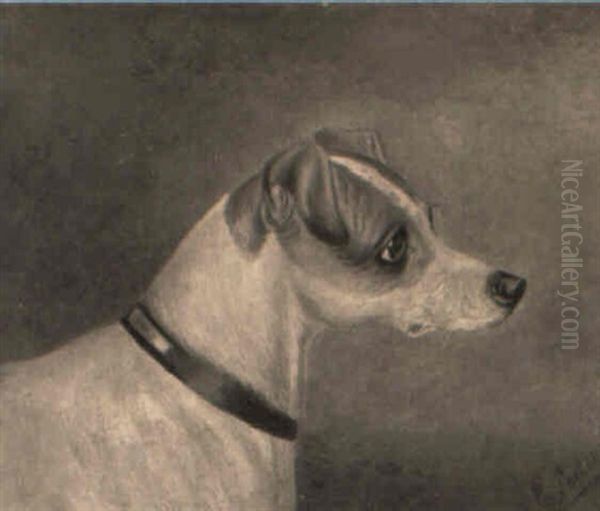

His style, while clearly influenced by his father, developed its own characteristics. Generally, sporting art of this period aimed for accuracy in depicting the specific animal, its conformation, and its characteristic pose or action. Loder's work would have strived for this verisimilitude. One of his known works, a painting of a "Jack Russell Terrier," showcases his ability to capture the alert and spirited nature of this popular breed. Such paintings were not merely decorative; they were records of prized animals, often reflecting their lineage or achievements in the field.

Compared to some of the giants of the genre, like the incomparable George Stubbs (1724-1806) with his profound anatomical understanding, or the dynamic and dramatic hunting scenes of Henry Alken (1785-1851), regional artists like Edwin Loder provided a more accessible, though perhaps less groundbreaking, contribution. Their work fulfilled a consistent demand and formed an important part of the broader tapestry of British art.

The Context of British Sporting Art in the 19th Century

To fully appreciate Edwin Loder's contribution, it's essential to understand the flourishing tradition of British sporting art in the 19th century. This era saw a continued passion for rural pursuits, and art that celebrated these activities was highly sought after. The landed gentry and increasingly the affluent middle class were keen patrons.

Early pioneers like Francis Barlow (c. 1626–1704), often called "the father of British sporting painting," and later John Wootton (c. 1682–1764) and James Seymour (1702–1752), had laid the groundwork. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, artists such as Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807), known for his elegant horse portraits, and Ben Marshall (1768-1835), who brought a new level of realism and character to equine art, had elevated the genre. Marshall famously stated he discovered "many a man who would pay fifty guineas for a painting of his horse, who would think ten guineas too much for a painting of his wife."

Edwin Loder's active period coincided with the high Victorian era, a time when sporting art was incredibly popular. Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) was a dominant figure, famed for his sentimental and anthropomorphic depictions of animals, particularly stags and dogs, which resonated deeply with Victorian sensibilities. His technical skill was immense, and his works were widely disseminated through engravings.

Other notable contemporaries included John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865), who was immensely popular for his coaching scenes, farmyard pictures, and racehorse portraits. His detailed and polished style was highly admired. Abraham Cooper (1787-1868) was another prolific painter of battle scenes, historical subjects, and, importantly, sporting animals, known for his vigorous portrayals. James Ward (1769-1859), a pupil of his brother-in-law George Morland (1763-1804), produced powerful animal paintings, often with a Romantic grandeur, though he also worked in a more conventional sporting vein.

The depiction of dogs was a significant sub-genre. Artists like Richard Ansdell (1815-1885), who often collaborated with Thomas Creswick on landscapes, was renowned for his scenes of Scottish sporting life, often featuring deerhounds and other hunting dogs. Later in the century, John Emms (1843-1912) became particularly celebrated for his lively and characterful paintings of foxhounds and terriers, often depicted in kennels or with hunt staff. His style was looser and more painterly than many of his predecessors. Maud Earl (1864-1943) also emerged as a leading dog painter towards the end of Loder's life, known for her sensitive and accurate canine portraits.

Depicting the Hunt and its Participants

Hunting scenes were a staple of sporting art, and artists like Loder would have been familiar with the conventions of depicting meets, the chase, and the kill. These paintings were not just about the animals but also about the social fabric of rural life. They often featured portraits of the Master of Foxhounds (MFH), prominent members of the hunt, and the hunt servants, such as the huntsman and whippers-in, alongside the pack of hounds.

The accuracy in depicting the "uniform" of the hunt – the distinctive coats of the hunt members – and the specific landscape of a particular hunt country was often important to patrons. While grand, panoramic hunt scenes were the domain of artists like John Ferneley Sr. (1782-1860) or Dean Wolstenholme Sr. (1757-1837) and his son Dean Wolstenholme Jr. (1798-1882), smaller commissions might focus on a favorite hunter (horse) or a group of hounds. Edwin Loder's work would likely have catered to this latter market, providing more intimate portrayals.

The depiction of hounds required a keen eye for their collective movement as a pack, as well as the individual characteristics that distinguished one hound from another, at least to the discerning eye of their master. The energy and dynamism of the chase were key elements, though portraiture of hounds at rest, perhaps in the kennel, was also common.

Canine Companions and Equine Portraits

Beyond the hunt, individual animal portraits were a significant part of Edwin Loder's output. His "Jack Russell Terrier" is indicative of this. Terriers, in particular, were popular subjects, valued for their pluck and character. Paintings of gundogs – pointers, setters, spaniels, and retrievers – were also in demand, often shown in characteristic poses: a pointer "on point," a spaniel flushing game, or a retriever with a downed bird. These images celebrated the dog's working abilities and its bond with its owner.

Equine portraiture remained central. Owners of racehorses, hunters, and carriage horses commissioned paintings as records of their prized possessions and, in the case of racehorses, their champions. The convention, established by artists like Stubbs and refined by Marshall and Herring, was often a profile or slightly angled view, emphasizing the horse's conformation, musculature, and sleek coat. The setting might be a stable, a paddock, or a racecourse. Edwin Loder, following his father's example, would have been adept at these conventional portrayals. The subtle differences in breed, the specific markings, and the overall "presence" of the horse were all crucial details.

Artists like Philip Reinagle (1749-1833) also contributed significantly to animal painting, particularly sporting dogs and game birds, often with detailed landscape settings, bridging the gap between pure animal portraiture and fuller sporting scenes.

Challenges and Comparisons in a Crowded Field

It is sometimes noted in art historical accounts that Edwin Loder's talents, while competent, were perhaps not considered to be on the same level as his father, James Loder. Such comparisons are often subjective and depend on the criteria used. James Loder established a solid reputation in Bath, and Edwin continued this tradition. In a field crowded with exceptional talent, from the anatomical genius of Stubbs to the dramatic flair of Alken or the polished sentimentality of Landseer, many capable artists like Edwin Loder carved out successful regional careers.

The demand for sporting art was such that there was room for artists of varying degrees of innovation and technical brilliance. Patronage was not solely confined to the aristocracy seeking masterpieces from the leading London names; local squires, farmers, and sporting enthusiasts across the country sought competent and pleasing representations of their animals and their way of life. Edwin Loder served this market in Bath and its environs.

His work, like that of many regional sporting artists, provides valuable historical documentation. These paintings offer insights into the types of animals favored, the equipment used in sporting pursuits, and the landscapes of the time. They are part of a visual culture that celebrated a particular aspect of British identity.

Edwin Loder's Place in Art History

Edwin Loder of Bath is best understood as a diligent practitioner within a well-established and popular genre. He inherited an artistic legacy from his father and continued to serve the demand for animal and sporting portraiture in his locality. While he may not have introduced radical innovations or achieved the national fame of some of his contemporaries, his work is part of the broad and fascinating tradition of British sporting art.

His paintings, such as the "Jack Russell Terrier," demonstrate a capable hand and an understanding of animal subjects. He contributed to the visual record of 19th-century sporting life, a period when such art was at its zenith of popularity. His connection to Bath also highlights the importance of regional artistic centers outside of London.

The study of artists like Edwin Loder enriches our understanding of the art market and patronage systems of the past. Not every artist can be a groundbreaking innovator, but those who competently and conscientiously ply their trade, fulfilling the needs and desires of their community, play a vital role in the cultural life of their time. Edwin Loder was one such artist, a painter of Bath who dedicated his career to the animals that were so integral to the British countryside and its sporting traditions.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

The legacy of Edwin Loder, like that of many sporting artists of his era, lies in the honest and affectionate portrayal of animals that held a special place in the lives of their owners. His work, and that of his father James, forms part of a continuous thread in British art that celebrates the bond between humans and animals, and the enduring allure of rural sports. While the grand narratives of art history often focus on the most famous names, the contributions of regional artists like Edwin Loder of Bath provide a fuller, more nuanced picture of the artistic landscape of their time. His paintings remain as charming records of a bygone era, appreciated by collectors of sporting art and those with an interest in the social history of 19th-century Britain. The enduring appeal of these subjects ensures that artists like Edwin Loder will continue to find an appreciative audience.