Elisabeth Anna Maria Jerichau-Baumann stands as a fascinating figure in 19th-century European art. Born in Warsaw and later becoming a Danish citizen, her life and work traversed national boundaries and artistic conventions. Active from the 1840s until her death in 1881, she navigated the complexities of being a female artist in a male-dominated world, achieving remarkable international success even while facing resistance within her adopted homeland. Her oeuvre, characterized by Romantic sensibilities and a pioneering engagement with Orientalist themes from a distinctly female perspective, continues to intrigue art historians and audiences alike. This exploration delves into her life, education, artistic evolution, key works, relationships with contemporaries, and lasting legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Düsseldorf

Born Anna Maria Elisabeth Baumann in Żoliborz, a borough of Warsaw, on November 21, 1819, she grew up in what was then Congress Poland, part of the Russian Empire. Her parents, Philip Adolph Baumann, a German mapmaker, and Johanne Frederikke Reyer, also of German descent, provided a background that was culturally Germanized within a Polish environment. This dual cultural exposure would subtly inform her later cosmopolitan outlook. Showing artistic talent early on, the young Elisabeth sought formal training, a challenging prospect for women at the time.

Around 1838, she made her way to Germany and enrolled in the prestigious Düsseldorf Academy of Art (Kunstakademie Düsseldorf), a major center for the German Romantic movement. This was a significant step, as few academies readily accepted female students. Her studies there, lasting until approximately 1844, were crucial in shaping her technical skills and artistic direction. The Düsseldorf School was known for its detailed style, often applied to historical, religious, or landscape subjects, emphasizing narrative and sentiment.

Crucially, during her time in Düsseldorf, she studied under Peter von Cornelius. Cornelius, a leading figure of the Nazarene movement and the first director of the Düsseldorf Academy after its reorganization, was notably progressive in his willingness to teach female students. His influence, rooted in a revival of Renaissance ideals and large-scale historical compositions, likely provided Jerichau-Baumann with a strong foundation in academic drawing and composition, even if her later style evolved distinctively. The environment also exposed her to contemporaries associated with the school, such as the landscape painters Andreas Achenbach and Oswald Achenbach, though her focus would primarily remain on the human figure.

Roman Years and a Pivotal Union

Following her studies, like many artists seeking classical inspiration and a vibrant international artistic community, Elisabeth Baumann moved to Rome in 1845. The city was a magnet for artists from across Europe, offering exposure to ancient ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and a lively expatriate scene. It was here that her personal and professional life took a decisive turn.

In Rome, she met Jens Adolf Jerichau, a promising Danish sculptor who was already gaining recognition. Jerichau, associated with the legacy of the great Danish Neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, was deeply embedded in the academic traditions favored in Copenhagen. Despite their different national backgrounds and artistic mediums, they formed a connection and married in 1846. This union transformed Elisabeth Baumann into Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, linking her fate inextricably with Denmark.

Her time in Rome was productive. She continued to paint, absorbing the influences of the Italian environment and interacting with the international circle of artists. Her work from this period likely reflected the prevailing Romantic tastes, possibly incorporating Italian settings or themes inspired by her surroundings. The marriage, however, set the stage for her eventual relocation to her husband's homeland.

Navigating Copenhagen: An Outsider's Perspective

In 1849, the couple moved to Copenhagen. Jens Adolf Jerichau was appointed a professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1849, solidifying his position within the Danish art establishment. For Elisabeth, however, the transition was more complex. Denmark at the time was deeply invested in its own National Romantic movement, often referred to as the Danish Golden Age, which emphasized local landscapes, everyday life, and a specific Nordic sensibility championed by figures like C.W. Eckersberg and his students earlier in the century.

Jerichau-Baumann, with her Polish birth, German training, and international experience gained in Rome, did not easily fit into the prevailing artistic climate of Copenhagen. Her style was perceived by some as too dramatic, too colorful, perhaps too "foreign" compared to the more restrained and introspective Danish taste. Furthermore, as a woman operating in the highly structured and male-dominated Danish art world, she faced inherent biases. She was often seen primarily as "the sculptor's wife," and her artistic ambitions were not always taken as seriously as those of her male counterparts.

Despite her husband's influential position, which undoubtedly provided some level of access and support, she struggled for full acceptance within the core Danish art institutions. Her background and gender marked her as an outsider, a status that would persist throughout her career in Denmark, even as her reputation grew significantly abroad. This tension between local resistance and international acclaim became a defining characteristic of her professional life.

Romanticism, History, and National Identity

While perhaps not fully aligned with the specific aesthetics of the Danish Golden Age, Jerichau-Baumann's work was deeply imbued with the broader spirit of European Romanticism. Her paintings often featured dramatic narratives, emotional intensity, and a rich, sometimes theatrical, use of color and light. She engaged with historical and literary themes, reflecting the Romantic fascination with the past and with powerful human stories.

She did attempt to connect with Danish national themes, most notably in her painting Mother Denmark (Moder Danmark), completed in 1851. This allegorical work depicts a strong, blonde female figure embodying the nation, holding a Dannebrog flag and incorporating symbols of Danish history and landscape. It represents an effort to contribute to the national narrative, blending idealized femininity with symbols of Danish identity, attempting to bridge her international style with local sentiment.

Her most famous work engaging with Danish history is arguably A Wounded Danish Soldier (En såret dansk kriger), painted around 1865 (sometimes dated 1866). This poignant image shows a soldier being tended to by a woman, likely his fiancée or wife. Created in the aftermath of the Second Schleswig War (1864), a traumatic national defeat for Denmark, the painting resonated with themes of sacrifice, loss, and care. While depicting a somber moment, it was interpreted by some as embodying resilience. This work achieved significant international recognition, showcasing her ability to handle emotionally charged subjects with sensitivity and skill, even if its reception within Denmark was complex due to the painful historical context. Compared to the national landscapes of contemporaries like P.C. Skovgaard or Johan Thomas Lundbye, her focus remained firmly on human drama.

Her portraiture also formed a significant part of her output. She painted prominent figures, including the famous Danish actress Johanne Luise Heiberg in 1852. These portraits often display a psychological depth and a focus on capturing the sitter's personality, rendered with her characteristic rich palette and attention to detail.

The Call of the Orient: Travels and Artistic Innovation

A defining aspect of Jerichau-Baumann's career was her engagement with Orientalism. Unlike many male Orientalist painters who often depicted the East through a lens of exoticism, fantasy, and sometimes colonial superiority, Jerichau-Baumann brought a different perspective, shaped by her own travels and her identity as a woman.

Her first major journey to the East took place in 1869-1870, when she traveled extensively through the Ottoman Empire (including Turkey) and Egypt in North Africa. She later undertook further travels to the region. These experiences provided her with firsthand exposure to the cultures, landscapes, and people of the Near East, profoundly impacting her artistic output. She documented her travels not only in sketches and paintings but also in written accounts, later published as Brogede Reisebilleder (Motley Travel Pictures).

Her Orientalist paintings are notable for their focus on women, particularly within domestic spaces like harems or private courtyards. Works such as An Egyptian Fellah Woman with her Child (1872) and numerous scenes depicting harem life showcase her interest in the daily lives and experiences of women in these cultures. While still engaging with the visual richness and "exotic" appeal associated with Orientalism, her depictions often convey a greater sense of empathy and individuality compared to the more objectified portrayals common among male artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme.

She seemed particularly fascinated by the textures of fabrics, the play of light in interiors, and the intimate moments of female life. Her paintings often feature vibrant colors, intricate details of clothing and décor, and a palpable sense of atmosphere. While working within the Orientalist genre, popularised earlier by artists like Eugène Delacroix, Jerichau-Baumann carved out a niche that reflected her unique access and perspective as a female visitor, offering glimpses into spaces often inaccessible to men. Her works like Two Young Turkish Women or portraits of figures like Princess Alexandra of Denmark and her sister Princess Dagmar of Denmark (later Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia) in Eastern-inspired settings further cemented her reputation in this genre.

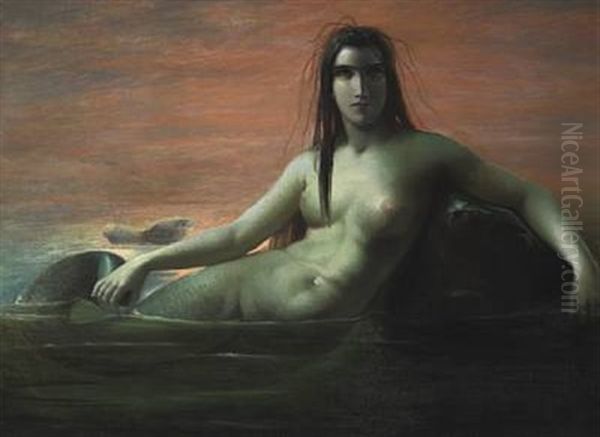

The Enigmatic Mermaid

Alongside historical subjects and Orientalist scenes, Jerichau-Baumann developed a particular fascination with the motif of the mermaid. This mythical creature, embodying duality – part human, part fish; alluring yet potentially dangerous; belonging to two realms but fully at home in neither – held a strong appeal for the Romantic imagination. For Jerichau-Baumann, it may also have resonated with her own sense of existing between cultures (Polish/Danish) or perhaps symbolized aspects of female identity and confinement.

She painted numerous variations on the mermaid theme throughout her career. These works often depict the mermaid in moments of longing, contemplation, or interaction with the human world. Rendered with her characteristic sensuousness and attention to detail, these paintings explore themes of myth, fantasy, and the mysterious depths of the sea and the psyche.

Her mermaid paintings were exhibited internationally, contributing significantly to her fame. Notably, she showed mermaid works at the London International Exhibition of 1862 and the Vienna World's Fair of 1873. These exhibitions brought her depictions of the mythical creature to a wide audience, where they were admired for their imaginative power and technical execution. A work simply titled Mermaid from 1873 is often cited as a key example of her engagement with this captivating subject.

International Acclaim versus Danish Reserve

The contrast between Jerichau-Baumann's reception abroad and at home in Denmark is striking. While she struggled for full integration into the Copenhagen art scene, her work found enthusiastic audiences and patrons elsewhere in Europe. She exhibited regularly and successfully in major art centers like Paris, London, Vienna, and Berlin.

Her participation in international exhibitions, such as the Paris Salons and the World Fairs, brought her widespread recognition. Her paintings were admired for their technical skill, vibrant colors, and engaging subject matter, particularly her Orientalist scenes and mermaid depictions. She cultivated connections with international patrons, including aristocracy and even royalty. Famously, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom acquired some of her work, a significant mark of prestige.

This international success stood in stark contrast to the more muted reception in Denmark. While acknowledged, she was never fully embraced by the Royal Danish Academy or the critical establishment during her lifetime. The reasons were likely multifaceted: her "foreignness" in terms of origin and training, her style that deviated from Danish norms, and the pervasive gender bias against ambitious female artists. Her success abroad might have even fueled some local resentment or skepticism. She remained, in many ways, an international star with a complicated relationship with her adopted national context.

Connections and Contemporaries

Jerichau-Baumann's career unfolded amidst a rich tapestry of 19th-century European art. Her closest artistic relationship was undoubtedly with her husband, Jens Adolf Jerichau. While supportive, their artistic paths differed; his sculpture adhered more closely to Neoclassical and Danish national ideals, while her painting embraced a more cosmopolitan Romanticism and Orientalism.

Her education under Peter von Cornelius connected her to the German Romantic and Nazarene traditions. Her time in Düsseldorf placed her in the orbit of the Düsseldorf School painters like Andreas Achenbach. In Rome, she would have been aware of the lingering influence of Bertel Thorvaldsen and the international community of artists residing there.

Her travels and exhibitions brought her into contact, or at least dialogue, with the major currents of European art. Her Orientalist works engage with a genre dominated by French artists like Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme, though offering her distinct perspective. Her interactions with prominent figures like the French Realist Gustave Courbet and the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, though perhaps brief, indicate her movement within significant European art circles.

As a successful female artist, she can be contextualized alongside other women who achieved prominence in the 19th century, such as the French animal painter Rosa Bonheur. While their styles and subjects differed, they both navigated the challenges of building careers in a male-centric art world. Within Denmark, her career predates the later breakthroughs of the Skagen Painters, which included notable female artists like Anna Ancher, who represented a different generation and artistic movement (Realism and Impressionism). Jerichau-Baumann's pioneering efforts, however, helped pave the way for greater acceptance of women artists in subsequent decades.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann passed away in Copenhagen on July 11, 1881. Although not fully celebrated in Denmark during her lifetime, her reputation has grown considerably since her death. She is now recognized as a significant figure in both Danish and Polish art history, as well as a notable contributor to European Romanticism and Orientalism.

Her influence extends in several directions. Firstly, she stands as a pioneer for female artists in Scandinavia and beyond. Her determination to pursue a professional career, her international success, and her focus on female subjects and perspectives challenged the conventions of her time and provided an important precedent for later generations of women artists. Her work is increasingly studied through the lens of feminist art history, highlighting her exploration of female identity, agency, and experience.

Secondly, her contribution to Orientalism is undergoing re-evaluation. While historically part of a complex and sometimes problematic genre, her work is often seen as offering a more nuanced, "decentered" perspective, particularly in her depictions of women. Her firsthand travel experiences and her position as a woman potentially allowed for different kinds of access and empathy compared to her male contemporaries. Her travelogue, Brogede Reisebilleder, also remains a valuable document for understanding 19th-century European perceptions of and interactions with the Near East.

Thirdly, her artistic style, with its blend of Romantic drama, detailed realism, and vibrant color, continues to attract interest. Her technical skill, particularly in rendering textures, light, and human emotion, is evident throughout her diverse body of work, from historical paintings and portraits to Orientalist scenes and mythical subjects like the mermaid.

Today, her paintings are held in major museums in Denmark (like the National Gallery of Denmark - SMK, and the Hirschsprung Collection), Poland, and internationally. Exhibitions dedicated to her work have helped to shed new light on her achievements and her unique position straddling multiple cultures and artistic traditions.

Conclusion

Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann's life and art offer a compelling narrative of talent, ambition, and resilience. As a Polish-born artist who became a Danish citizen, trained in Germany, honed her craft in Italy, and traveled extensively in the Near East, she embodied a cosmopolitan spirit. Her work reflects this rich blend of influences, merging Romantic sensibilities with detailed observation, and engaging with grand historical themes as well as intimate portrayals of female life and mythical fantasy. While facing the dual challenges of being a woman and something of an outsider in the Danish art world, she achieved remarkable international success, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be admired for its skill, vibrancy, and unique perspective. She remains a significant figure, not only for her artistic contributions but also for her role in challenging the boundaries imposed on female artists in the 19th century.