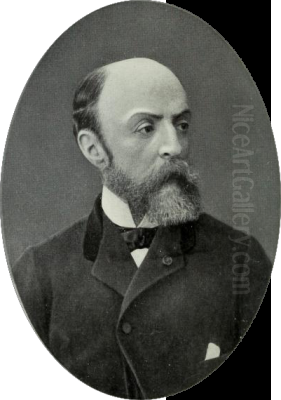

Eugène Fromentin stands as a unique figure in nineteenth-century French culture, a man equally gifted with the brush and the pen. Born in La Rochelle on October 24, 1820, and dying in the same city on August 27, 1876 (though some sources state his birth date as December 24), Fromentin carved a distinct niche for himself through his evocative depictions of North Africa and his insightful writings on art and life. He navigated the currents of Romanticism and Realism, ultimately becoming one of the most respected Orientalist painters of his generation, while also achieving lasting fame as a novelist and art critic.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Eugène-Samuel-Auguste Fromentin hailed from La Rochelle, a port city on France's Atlantic coast. His initial path seemed destined for law, a field he briefly pursued in Paris. However, the allure of art proved stronger. He sought training under the landscape painter Louis Cabat, an artist associated with the Barbizon school's precursors, known for his sensitive renderings of nature. This early training grounded Fromentin in the principles of landscape painting, but his true artistic voice would emerge through experiences far from the forests of Fontainebleau.

A pivotal moment came early in his career. Fromentin developed a deep fascination with lands across the Mediterranean. This interest would soon transform into direct experience, shaping the entire trajectory of his artistic and literary output. His initial academic training provided a foundation, but it was the light, colours, and cultures of North Africa that would truly ignite his imagination.

The Call of the Orient: Algerian Journeys

In 1846, Fromentin embarked on the first of several influential journeys to Algeria. This initial visit, undertaken at a relatively young age, left an indelible mark. He was among the earliest French artists to explore Algeria not just as a colonial territory, but as a source of profound artistic inspiration. The landscapes, the quality of light, the architecture, and the daily lives of the Algerian people captivated him.

He returned to North Africa multiple times, including a significant trip in 1852-1853, partly accompanying an archaeological mission. These travels allowed him to immerse himself deeply in the region's environment and customs. He meticulously observed the details of Arab life, the interactions between people, the elegance of horsemen, and the vastness of the desert landscapes. These experiences provided a rich repository of sketches, memories, and insights that would fuel his work for decades. Fromentin wasn't merely a tourist; he was an ethnographer with a paintbrush, seeking to understand and represent a world vastly different from his own.

Orientalist Vision: Style and Themes

Fromentin's art belongs firmly within the Orientalist movement, a trend in Western art and literature fascinated with the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. However, his approach was nuanced. His work masterfully blends the dramatic flair and emotional intensity of Romanticism, particularly influenced by the great Eugène Delacroix, with a keen eye for realistic detail. Unlike Delacroix's often tumultuous and violent scenes, Fromentin frequently focused on moments of quiet dignity, everyday activity, or the serene grandeur of the landscape.

His style is characterized by refined draftsmanship, subtle and harmonious colour palettes, and a remarkable sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He excelled at capturing the shimmering heat of the desert, the cool transparency of shadows, and the delicate gradations of the North African sky. His brushwork, often described as delicate and precise, conveyed both the textures of the environment and the perceived elegance of its inhabitants, especially the Arab horsemen and their steeds, which he depicted with particular admiration.

While deeply influenced by Romanticism, Fromentin maintained a commitment to accuracy born from direct observation. This gives his work a distinct quality, less overtly theatrical than some Orientalists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, but imbued with a sense of lived experience. His paintings often possess an ethnographic value, offering detailed glimpses into the clothing, customs, and environments of mid-19th century Algeria. He consciously distanced himself from the later Impressionist movement, criticizing what he saw as their neglect of structure and finished detail in favour of fleeting optical effects.

Masterpieces of the Brush

Fromentin's talent gained early recognition. His Gorges de la Chiffa (Gorges of the Chiffa), exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1847, was a significant success, establishing his reputation as a painter of North African scenes. This work showcased his ability to render dramatic landscapes with both accuracy and atmospheric depth.

Throughout his career, he produced numerous celebrated paintings. The Arab Falconer (Le Fauconnier Arabe), with versions painted around 1862-1863 (one now in the Louvre), is perhaps his most iconic theme. These works capture the noble bearing of the falconer and his bird against expansive, light-filled backdrops, embodying an idealized vision of Arab dignity and connection to nature. The related theme of the Falcon Hunt (Chasse au faucon), explored in works from the early 1860s, allowed him to depict dynamic action and the grace of horses in motion.

Other notable works reveal the breadth of his Orientalist subjects: Moorish Funeral (Enterrement Maure, 1853) presents a solemn procession with sensitivity; Audience with a Caliph (Audience chez un Chalife, 1859) depicts a scene of quiet authority; Kabyle Shepherd (Berger Kabyle, 1861) focuses on pastoral life; and Arab Couriers (Courriers arabes, 1861) captures the energy of messengers traversing the landscape. He also painted scenes like Night Thieves (Voleurs de Nuit, 1867) and Muleteers' Halt (Halte de muletiers, 1867), showcasing different facets of North African life. His Centaurs and Arabs Attacked by a Lioness (Centaures et Arabes attaqués par une lionne, 1867) ventured into more mythological or allegorical territory, reminiscent of Romantic masters like Delacroix or Théodore Géricault.

The Egyptian Sojourn

In 1869, Fromentin experienced another significant journey, this time to Egypt. He traveled as part of the entourage invited by Khedive Ismail Pasha for the lavish inauguration ceremonies of the Suez Canal. This trip brought him into contact with the landscapes and ancient monuments of Egypt, a different facet of the "Orient" than Algeria. He documented his impressions in diaries.

Although this journey reportedly resulted in fewer finished artworks compared to his Algerian travels – perhaps due to the official nature of the visit or his evolving focus – it nonetheless left its mark. Paintings such as The Nile (Le Nil, ca. 1870-1876), Upper Egypt (Haute-Egypte), Memory of Esneh (Souvenir d'Esneh, 1875), and the celebrated Egyptian Women on the Banks of the Nile (Femmes égyptiennes au bord du Nil, 1876, now at the Musée d'Orsay) demonstrate his continued engagement with North African themes, capturing the distinct atmosphere and light of the Nile Valley in his characteristically refined style.

The Literary Path: Fromentin the Writer

Parallel to his painting career, Fromentin cultivated a significant literary reputation. His travels provided direct material for two highly regarded travelogues: Un Été dans le Sahara (A Summer in the Sahara, published serially 1854, book form 1857) and Une Année dans le Sahel (A Year in the Sahel, 1859). These works are far more than simple travel accounts; they are rich with painterly descriptions, sensitive observations of culture and landscape, and personal reflections. They offer invaluable insight into his artistic process and his deep engagement with the places he visited.

Fromentin achieved perhaps his greatest literary fame with the novel Dominique (1862). This largely autobiographical work tells the story of an unfulfilled youthful love and the protagonist's subsequent retreat into a quiet country life. Praised for its subtle psychological analysis, elegant prose, and melancholic tone, Dominique is considered a minor classic of French literature, often compared in its introspective quality to Benjamin Constant's Adolphe or Madame de La Fayette's La Princesse de Clèves. It secured Fromentin's place as a respected man of letters.

A Critic's Eye: Les Maîtres d'autrefois

Towards the end of his life, Fromentin produced another landmark work, this time in the field of art criticism: Les Maîtres d'autrefois (The Masters of Past Time, often translated as The Old Masters), published in 1876, the year of his death. Subtitled "Belgium–Holland," the book is an account of a journey through the Low Countries, framed as a series of visits to museums and reflections on the art of Dutch and Flemish masters.

This book was groundbreaking. Fromentin brought his painter's eye and writer's sensibility to the analysis of artists like Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt van Rijn, Frans Hals, Jacob van Ruisdael, and others. He moved beyond simple description or historical cataloguing, delving into the techniques, compositional strategies, and emotional content of the works. He offered personal, often subjective, yet deeply insightful interpretations, attempting to understand the "soul" of the artists and their connection to their time and place. Les Maîtres d'autrefois is considered one of the foundational texts of modern art criticism, admired for its perceptive analysis and elegant style. It notably influenced later artists and writers, including Vincent van Gogh, who read it with great interest.

Influences and Connections

Fromentin's artistic lineage connects him to several key figures. His teacher, Louis Cabat, provided his initial grounding. The towering figure of Eugène Delacroix was a constant reference point, particularly for his use of colour, dynamic compositions, and engagement with Orientalist themes, though Fromentin developed a more restrained and polished style. He also admired the atmospheric landscapes of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. His deep study of the Old Masters, especially Rubens and the Dutch Golden Age painters like Rembrandt, profoundly informed his understanding of technique and composition, as evidenced in Les Maîtres d'autrefois.

As an established figure, Fromentin moved within the artistic and literary circles of his time. He was a respected exhibitor at the official Salons. While critical of the emerging Impressionists, his work shared the 19th-century French preoccupation with light and landscape. He was part of the broader Orientalist movement that included contemporaries like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, and Prosper Marilhat, each offering their own interpretations of the East. His dual identity as a painter and writer gave him a unique standing among his peers.

Later Years and Legacy

Sources suggest that Fromentin's later years were marked by declining health, which may have impacted his artistic production and energy. The meticulous finish and demanding detail of his paintings required considerable stamina. He died relatively young, at the age of 55, in his hometown of La Rochelle.

Despite a career cut short, Eugène Fromentin left a rich and multifaceted legacy. As a painter, he is remembered as a leading Orientalist, whose works offer a refined, sensitive, and often idealized vision of North Africa. His paintings are admired for their technical skill, harmonious colours, and evocative atmosphere. They provide valuable visual records of Algeria and Egypt in the mid-19th century, filtered through a distinctly European Romantic sensibility.

As a writer, his travelogues remain compelling accounts of cross-cultural encounters, while Dominique holds its place as a significant psychological novel. His most enduring written contribution, however, might be Les Maîtres d'autrefois, which pioneered a new, more personal and analytical approach to art criticism and continues to be read by art historians and enthusiasts today. Fromentin exemplifies the "painter-writer," a figure whose creativity flowed seamlessly between visual and literary expression, enriching both fields.

Conclusion

Eugène Fromentin occupies a distinctive place in the landscape of 19th-century French art and literature. Driven by a profound fascination with North Africa, he translated his experiences into paintings of remarkable elegance and sensitivity, becoming a key figure in the Orientalist movement. Simultaneously, he crafted literary works of lasting value, from evocative travel narratives and a poignant novel to a seminal text of art criticism. His dual talents allowed him to explore themes of cultural encounter, memory, and artistic creation with a unique depth and perspective. Fromentin's work continues to offer both aesthetic delight and valuable insight into the complex relationship between Europe and the Orient in his time.