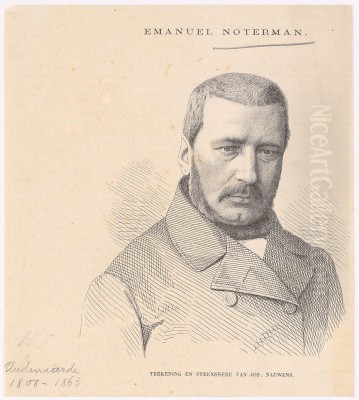

The 19th century witnessed a burgeoning of artistic talent across Europe, with Belgium emerging as a particularly vibrant hub for painters exploring diverse genres. Within this dynamic environment, Emmanuel Zacharias Noterman (1808-1863) carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming a celebrated figure for his charming and often humorous depictions of animals, particularly in the whimsical tradition of "singeries" – scenes of monkeys aping human behavior. His work, characterized by technical skill and a keen observational eye, offers a delightful window into the tastes and sensibilities of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Ghent and Antwerp

Emmanuel Zacharias Noterman was born in April 1808 in Ghent, a city with a rich artistic heritage in Belgium. His father, Jean Noterman, was a painter and decorator, suggesting that young Emmanuel was exposed to the world of art from an early age. His mother was Marie-Catherine Haelterman. This familial connection to the arts likely played a role in shaping his future path. He was the elder brother of Zacharias Noterman (1820-1890), who would also become a painter, similarly known for his animal scenes and especially his engaging singerie compositions. It is plausible that Emmanuel provided some initial guidance to his younger sibling, fostering a shared artistic interest within the family.

To hone his innate talents, Emmanuel Noterman pursued formal artistic training. He enrolled at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. This institution was a cornerstone of artistic education in Belgium, attracting aspiring artists from across the region and beyond. Under the tutelage of respected masters, Noterman would have received a rigorous academic grounding in drawing, composition, and painting techniques, essential for any artist aiming for professional recognition. Antwerp, with its bustling port and rich cultural history, including the legacy of Old Masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, provided an inspiring backdrop for his studies.

The Rise of Animal Painting and the Singerie Tradition

The 19th century saw a significant rise in the popularity of animal painting. This was partly fueled by a growing middle-class clientele who appreciated subjects that were relatable, decorative, and often imbued with sentimental or narrative qualities. Artists like Eugène Joseph Verboeckhoven, known for his meticulously rendered sheep and cattle, achieved immense success in Belgium. In France, Rosa Bonheur captivated audiences with her powerful depictions of horses and other livestock, while in Britain, Sir Edwin Landseer became a household name with his emotive portrayals of dogs and stags.

Within this broader trend, the subgenre of "singerie" (from the French word "singe" for monkey) enjoyed a particular vogue. These were satirical or humorous scenes where monkeys, dressed in human attire, engaged in human activities – playing cards, making music, dining, or even conducting scholarly pursuits. The tradition had roots in Flemish art of the 17th century, with artists like David Teniers the Younger and his brother Abraham Teniers popularizing such comical scenes. Nicolaes van Verendael also contributed to this early development. The genre continued into the 18th century, particularly in France with artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau and Christophe Huet, who decorated Rococo interiors with charming monkey arabesques. Emmanuel Noterman, alongside his brother Zacharias, became one of the foremost Belgian proponents of this tradition in the 19th century, adapting it to contemporary tastes.

Noterman's Artistic Style: Humor, Detail, and Narrative

Emmanuel Noterman's artistic style is characterized by a delightful blend of meticulous realism in the rendering of his animal subjects and a playful, often satirical, approach to his narrative themes. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the textures of fur and feathers, the expressive glances of his animal protagonists, and the intricate details of their surroundings.

His singerie paintings are particularly noteworthy. In these works, monkeys are not merely amusing caricatures but are often imbued with a surprising degree of character. Whether depicted as quack doctors, earnest musicians, or boisterous drinkers, Noterman's monkeys parody human foibles and societal customs with a lighthearted touch. The humor in these scenes is gentle rather than biting, inviting amusement rather than harsh critique. He paid close attention to costume and props, further enhancing the illusion of monkeys participating in the human world. This attention to detail extended to the settings, which were often richly appointed interiors or carefully composed still-life elements.

Beyond monkeys, Noterman was also an accomplished painter of dogs. His canine portraits and genre scenes featuring dogs often convey a sense of warmth and affection, capturing the loyal and companionable nature of these animals. These works resonated with the pet-loving sensibilities of the Victorian era. His technical skill allowed him to depict various breeds with accuracy and vivacity.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into Noterman's World

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be extensive, several known works exemplify Emmanuel Noterman's thematic concerns and artistic skill.

Singeries: Many of his most recognizable works fall into this category. Titles like The Monkey Musician, Monkey Business, The Dice Players and the Dog (which often featured monkeys as the primary players), and The Morning Shave and Reading the Paper (likely depicting monkeys in these domestic routines) highlight his engagement with this genre. These paintings would typically feature small groups of monkeys in elaborate, human-like scenarios, often with a humorous or anecdotal quality. For instance, The Monkey Musician might show a capuchin earnestly playing a violin or flute, perhaps comically out of tune, surrounded by other monkeys feigning connoisseurship.

Dog Paintings: Works such as Dogs Resting showcase his ability to capture the relaxed, natural poses of canines. A piece titled Portrait of a girl with her dog (dated 1858) indicates his skill in combining human portraiture with animal painting, a popular format at the time. These paintings often emphasized the bond between humans and their animal companions or simply celebrated the inherent charm of the animals themselves.

The specific details of composition, color palette, and narrative in each piece would vary, but a consistent thread of skilled draftsmanship and engaging storytelling runs through his oeuvre. His paintings were typically executed in oil on canvas or panel, often of a modest size suitable for domestic interiors.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Exhibitions

Emmanuel Noterman was active during a period of rich artistic exchange. He established studios in both Antwerp and Brussels, the two major art centers of Belgium. He regularly exhibited his works in the Salons of these cities, which were crucial venues for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and engage with their peers.

The art world of 19th-century Belgium was a relatively close-knit community. Noterman is known to have collaborated with Jean Pierre François Lamorinière (1828-1911), a respected landscape painter. In such collaborations, it was common for a specialist in one area (like Noterman with animals) to contribute figures or animals to a landscape painted by another artist, or vice versa, creating a richer, more complex composition. Lamorinière was known for his detailed, often melancholic forest scenes and panoramic views, and Noterman's lively animal figures would have added a distinct narrative element to these settings.

His works were also exhibited alongside those of other prominent contemporaries. For example, records indicate his paintings were shown in Brussels in proximity to works by the Austrian Biedermeier painter Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793-1865), known for his portraits, genre scenes, and landscapes. This suggests Noterman was part of the broader European artistic conversation.

Other Belgian animal painters active during or overlapping with Noterman's career include Eugène Joseph Verboeckhoven (1798-1881), who was immensely popular for his pastoral scenes with sheep and cattle, and Louis Robbe (1806-1887), another specialist in depicting cattle and sheep with a realistic touch. Joseph Stevens (1816-1892) gained fame for his empathetic portrayals of dogs, often in urban settings, sometimes highlighting their struggles, which offered a different perspective compared to Noterman's more lighthearted approach. Joseph's brother, Alfred Stevens (1823-1906), though more famous for his elegant depictions of Parisian society women, also came from this artistically inclined Belgian milieu. Later in the century, Henriette Ronner-Knip (1821-1909), of Dutch origin but active for a long period in Brussels, became internationally renowned for her charming and incredibly detailed paintings of cats.

The broader context of Belgian art during Noterman's active period also included Romantic painters like Gustave Wappers and historical painters such as Hendrik Leys, who were instrumental in shaping the national school. While Noterman's genre was different, he operated within this national artistic revival.

The Noterman Brothers: A Shared Artistic Inclination

The fact that Emmanuel's younger brother, Zacharias Noterman, also pursued a career as an animal painter, specializing in very similar themes, particularly singeries, is noteworthy. Zacharias, who later moved to Paris, also achieved considerable success. It's interesting to speculate on their artistic relationship. Did they collaborate? Did they influence each other? Or was there a friendly rivalry? While detailed records of their personal interactions are scarce, their shared thematic focus suggests a strong familial inclination towards this particular niche of animal painting. Their father's profession as a painter and decorator might have laid the groundwork for both sons to pursue artistic careers. The success of both brothers in a similar field underscores the popularity of animal genre scenes during this period.

Anecdotes and Unanswered Questions

Specific, well-documented anecdotes about Emmanuel Zacharias Noterman's personal life or studio practice are not abundant in readily available historical sources, which is common for many artists who were well-regarded in their time but perhaps not of the absolute first rank of international celebrity. The "mysteries" surrounding his work are less about unsolved enigmas and more about the nuances of artistic interpretation and motivation common to the singerie genre.

Why the enduring appeal of monkeys dressed as humans? These scenes operated on multiple levels. They were undeniably amusing and decorative. They also offered a gentle form of social satire, allowing viewers to laugh at human follies as reflected in the antics of these primate mimics. There might also have been a subtle engagement with emerging scientific ideas about evolution and the relationship between humans and animals, though for Noterman, the primary intent appears to have been entertainment and charming social commentary rather than profound philosophical statements, unlike, for example, the later, more unsettling monkey paintings of Gabriel von Max.

The precise division of labor in his collaborations, such as with Lamorinière, or the extent of his direct influence on his brother Zacharias, remain areas where more detailed archival research could potentially shed further light.

Art Historical Positioning and Posthumous Evaluation

Emmanuel Zacharias Noterman is recognized as a skilled and charming practitioner of animal painting and the singerie genre within 19th-century Belgian art. While he may not have achieved the towering international fame of some of his contemporaries in other fields, like the history painter Nicaise de Keyser or later Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff, he was a respected artist in his own right and catered successfully to the tastes of his time.

His works are appreciated for their technical proficiency, their humor, and their contribution to a specific and delightful subgenre. Paintings by Emmanuel Noterman can be found in museum collections, including the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, attesting to his recognized status. His works also appear periodically on the art market, where they continue to attract collectors who appreciate the whimsy and craftsmanship of 19th-century animalier art.

In the broader narrative of art history, Noterman and his brother Zacharias represent an important continuation and popularization of the singerie tradition in the 19th century. They successfully adapted this older genre to contemporary sensibilities, ensuring its survival and appeal to a new generation of art lovers. His dedication to animal subjects places him firmly within the lineage of animalier painters, a diverse group that includes artists ranging from the highly academic to the more sentimentally inclined.

His legacy is that of an artist who brought joy and amusement to his audience through skillfully rendered and imaginatively conceived scenes. He captured a particular facet of 19th-century taste, one that valued narrative, humor, and the charming depiction of the animal world. Artists like Charles Verlat, who also painted animals and later became a director of the Antwerp Academy, would have been aware of Noterman's contributions.

Conclusion: An Enduring Charm

Emmanuel Zacharias Noterman stands as a notable figure in 19th-century Belgian art, an artist who excelled in capturing the spirit and antics of the animal kingdom. His singerie paintings, in particular, remain a testament to his skill, humor, and ability to tap into a long-standing artistic tradition, infusing it with fresh vitality. While the grand historical narratives and avant-garde movements of the 19th century often dominate art historical discourse, artists like Noterman played a crucial role in shaping the diverse artistic landscape of their era, creating works that were admired, collected, and enjoyed by a broad public. His paintings continue to delight viewers today, offering a charming escape into a world where animals playfully mirror the complexities and comedies of human life. His contribution, alongside that of his brother and other contemporaries, ensures that the whimsical world of the singerie and the broader appeal of animal painting remain a cherished part of art history.