Edwin Douglas (1848-1914) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of British Victorian art. A proud Scotsman by birth and training, Douglas carved a distinguished career for himself, primarily celebrated for his exceptional ability to capture the spirit, form, and character of animals, with a particular and enduring fondness for dogs. His work, deeply rooted in the realist traditions of the era, resonated with the sensibilities of Victorian society, earning him acclaim, patronage, and a lasting place in the annals of animalier art. This exploration delves into the life, artistic journey, key works, influences, and enduring legacy of Edwin Douglas, an artist whose canvases continue to speak of a profound connection with the animal world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Scotland

Born in Edinburgh in 1848, Edwin Douglas emerged into a city renowned for its intellectual and artistic vibrancy. The Scottish capital, with its historic institutions and burgeoning cultural scene, provided a fertile ground for a young man with artistic inclinations. It was here, amidst the romantic landscapes and strong artistic traditions of Scotland, that Douglas's foundational artistic sensibilities were shaped. His formal training was undertaken at the prestigious Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh, an institution that had long been a cornerstone of Scottish art, nurturing generations of talented painters and sculptors.

At the RSA, Douglas would have been immersed in a curriculum that emphasized rigorous draughtsmanship, anatomical study, and the classical principles of composition. The Academy, while upholding traditional values, was also a place where contemporary artistic currents were discussed and absorbed. It was during these formative years that Douglas likely honed his observational skills, a crucial asset for an artist who would later specialize in the nuanced depiction of animal life. His early works, exhibited at the RSA starting in 1865, often focused on Scottish themes, historical scenes, and, increasingly, the animals that populated both the wild landscapes and domestic settings of his homeland. This early focus on local subjects and narratives was characteristic of many Scottish artists of the period, who sought to celebrate their national heritage and identity through their art.

The artistic environment in Scotland during Douglas's youth was dynamic. Artists like Horatio McCulloch were celebrated for their dramatic Highland landscapes, while genre painters such as Thomas Faed captured scenes of Scottish rural life with pathos and charm. The influence of earlier Scottish masters, including Sir David Wilkie, with his keen eye for character and narrative, also pervaded the artistic atmosphere. Douglas, while developing his own unique voice, was undoubtedly a product of this rich artistic milieu, absorbing its lessons and preparing to make his own mark.

The Move to London and Royal Academy Success

In 1871, seeking broader opportunities and a larger stage for his talents, Edwin Douglas made the pivotal decision to move to London. The metropolis was the undisputed center of the British art world, home to the Royal Academy of Arts (RA), a powerful institution that dictated artistic tastes and offered unparalleled exposure for aspiring artists. For a provincial artist, success in London, particularly at the RA's annual exhibitions, was the ultimate validation and a pathway to significant patronage.

Douglas's transition to London proved fruitful. He became a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy, where his works were generally well-received. The RA's exhibitions were major social and cultural events, attracting vast crowds and critical attention. To have one's work accepted and prominently displayed was a significant achievement. Douglas continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy until 1900, showcasing a considerable body of work over nearly three decades. In total, he is recorded as having exhibited forty-one paintings at the Royal Academy and other major London venues, a testament to his consistent productivity and acceptance within the established art circles.

His London career saw him reside in various locations, including Bedford Gardens, and later in Surrey, with periods in Dorking and Shere, near Guildford. These areas, offering a blend of proximity to the London art scene and the tranquility of the countryside, likely provided suitable environments for his work, which often required close observation of animals in natural or semi-natural settings. The move to England did not, however, mean an abandonment of his Scottish roots; he continued to paint Scottish subjects throughout his career, but his focus increasingly solidified around animal portraiture and genre scenes involving animals.

Artistic Style, Thematic Focus, and the Influence of Landseer

Edwin Douglas's artistic style is firmly situated within the realist tradition that dominated much of Victorian painting. He possessed a meticulous eye for detail, rendering the textures of fur, the glint in an animal's eye, and the subtle nuances of anatomy with remarkable precision. His approach was not merely photographic, however; Douglas imbued his animal subjects with a palpable sense of life and character. This was particularly evident in his depictions of dogs, which often displayed an emotional depth and a degree of anthropomorphism that greatly appealed to Victorian sentimentality. His animals were not just specimens; they were individuals with personalities, capable of loyalty, intelligence, and emotion.

A towering figure in British animal painting, Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (1802-1873), cast a long shadow over the genre, and Edwin Douglas was a profound admirer, often seen as following in Landseer's esteemed footsteps. Landseer, a favorite of Queen Victoria, had elevated animal painting to new heights of popularity and critical acclaim. His works, characterized by technical brilliance, narrative power, and a sympathetic portrayal of animals (often with moralizing undertones), set a benchmark for subsequent artists. Douglas shared Landseer's affinity for dogs and his ability to capture their expressive qualities. While Douglas developed his own distinct touch, the influence of Landseer's dramatic compositions and his empathetic approach to animal subjects is discernible in much of Douglas's oeuvre.

Beyond dogs, Douglas's thematic repertoire included other animals, often within the context of Scottish landscapes or historical settings. Hunting scenes, depictions of Highland ponies, and pastoral subjects also featured in his work. He was adept at creating a sense of atmosphere, whether it was the crisp air of a Highland hunt or the cozy interior of a domestic scene. His paintings often told a story, engaging the viewer's imagination and emotions, a hallmark of successful Victorian genre painting. The narrative element, combined with his technical skill, ensured the popularity of his work among a broad audience, particularly the burgeoning middle-class collectors who appreciated art that was both skillful and accessible.

Notable Works: A Canine Pantheon

Edwin Douglas's reputation rests heavily on his masterful paintings of dogs, capturing a wide array of breeds with an understanding of their specific characteristics and temperaments. Among his celebrated works are:

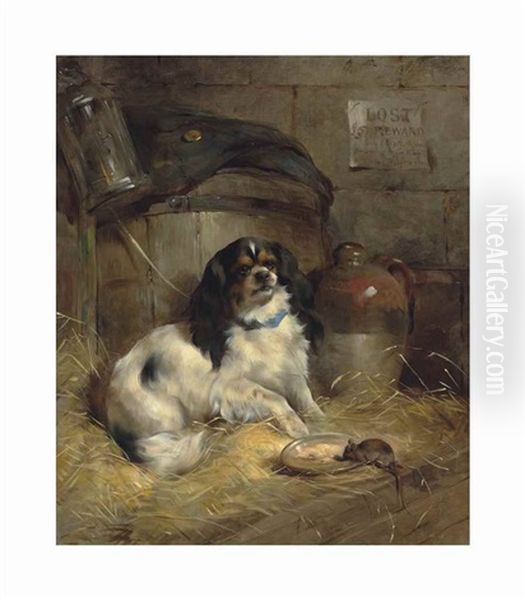

A Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1882): This painting, an oil on canvas measuring 32 ½ x 27 ½ inches, exemplifies Douglas's skill in portraying the charm and elegance of this popular breed. Such works appealed directly to the Victorian love for companion animals and the increasing interest in specific dog breeds. The painting would have showcased the dog's silky coat, expressive eyes, and gentle demeanor, likely set within a comfortable domestic interior or a carefully arranged naturalistic setting.

Yeoman’s Charger: This title suggests a painting of a sturdy, reliable horse, perhaps belonging to a yeoman farmer or a member of the yeomanry cavalry. Such a work would have allowed Douglas to display his understanding of equine anatomy and the character of a working animal, possibly evoking themes of loyalty, strength, and rural life.

The Deer-Path: This evocative title points towards a scene set in the Scottish Highlands, a landscape Douglas knew well. It might have depicted deer in their natural habitat or perhaps a hunting scene, focusing on the tension and atmosphere of the chase. The "deer-path" itself suggests a narrative element, a trail followed by either prey or predator, inviting the viewer into the wildness of the scene.

Willie and His Peers (also referred to as Willie and His Pets): This title strongly suggests a charming genre scene, likely featuring a child named Willie surrounded by his beloved animal companions. Such paintings were immensely popular in the Victorian era, appealing to sentiments about childhood innocence and the bond between humans and animals. The "peers" or "pets" would almost certainly have included dogs, perhaps of various breeds, showcasing Douglas's versatility.

Ready to Start: This title implies a scene of anticipation, very likely related to a hunt or a sporting activity. It could feature hounds eager for the chase, horses and riders preparing, or a gundog poised for action. Douglas excelled at capturing the dynamic energy and focused intensity of animals in such moments.

The Showman’s Girl: This painting likely depicted a young woman associated with a travelling show, perhaps with an animal performer. It offers a glimpse into a different facet of Victorian life and the role of animals in entertainment. The work could explore themes of companionship, performance, or the often-hard lives of itinerant entertainers.

The Doctor’s Pony: A subject that evokes a sense of reliability and service, the doctor's pony was a familiar sight in an era before widespread motorized transport. This painting would have celebrated the steadfastness of the animal, a crucial partner in the doctor's daily rounds, often traversing difficult terrain and enduring harsh weather.

The 12th of August: This date is famously known as the "Glorious Twelfth," the start of the grouse shooting season in Britain. A painting with this title would undoubtedly be a sporting scene, likely set in the Scottish moors, featuring hunters, gundogs (such as setters or pointers), and the dramatic landscape. Such works were highly sought after by the landed gentry and sporting enthusiasts.

These titles, and the paintings they represent, underscore Douglas's focus on narrative, his keen observation of animal behavior, and his ability to connect with the prevailing tastes and interests of his Victorian audience. His works were not merely animal portraits but often vignettes of life, imbued with emotion and a sense of story.

Influences, Contemporaries, and the Victorian Art World

Edwin Douglas operated within a vibrant and diverse Victorian art world. His primary influence, as noted, was Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, whose preeminence in animal painting set a high standard. Landseer's ability to combine anatomical accuracy with emotional appeal and narrative drama was something Douglas clearly aspired to and often achieved in his own right.

Beyond Landseer, the field of animal painting in Britain was robust. Briton Rivière (1840-1920) was another prominent contemporary known for his dramatic and often sentimental paintings of animals, frequently with classical or biblical themes. John Emms (1843-1912) specialized in painting dogs, particularly hounds and terriers, with a vigorous and direct style that captured their lively character, often in sporting contexts. Slightly later, but overlapping with the end of Douglas's career, Maud Earl (1864-1943) gained international fame for her refined and individualized portraits of purebred dogs. Across the Channel, the French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) achieved immense international success with her powerful and realistic depictions of animals, particularly horses and cattle, and her work was well-known and admired in Britain. George Armfield (c.1808-1893) was another popular painter of sporting dogs and terriers, whose works often featured lively, anecdotal scenes.

The Royal Academy exhibitions, where Douglas frequently showed his work, would have featured a wide array of artistic styles and subjects. He would have exhibited alongside leading figures of the era. These included classical painters like Lord Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), whose meticulously detailed scenes of ancient Greece and Rome were immensely popular. Genre painters capturing scenes of contemporary Victorian life, such as William Powell Frith (1819-1909), known for his bustling panoramas like Derby Day, were also major figures. The legacy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with artists like John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), continued to influence British art with their emphasis on truth to nature and detailed realism.

In Scotland, Douglas's contemporaries included landscape and seascape painter William McTaggart (1835-1910), celebrated for his increasingly impressionistic style, and portraitist Sir George Reid (1841-1913), who became President of the Royal Scottish Academy. While Douglas's specialization was distinct, he was part of this broader artistic firmament.

The user's provided list of contemporaries, while diverse, highlights the breadth of artistic practice during Douglas's lifetime:

Richard Doyle (1824-1883), an illustrator and caricaturist, notably for Punch magazine, known for his whimsical fairy illustrations.

Friedrich Johann Heinrich Drake (1805-1882), a German sculptor, prominent in Berlin.

Heinrich Dreber (Franz-Dreber) (1822-1875), a German landscape painter associated with the Deutschrömer (German Roman) artists.

Jules-Antoine Droz (1804-1872), a French sculptor.

James Drummond (1816-1877), a Scottish historical and genre painter, and curator of the National Gallery of Scotland. His focus on Scottish historical subjects would have resonated with Douglas's own early interests.

J. H. Drury (active late 19th century), likely an American artist, possibly associated with architectural rendering or the Chicago School, though less information is readily available to firmly place him in Douglas's immediate sphere of interaction.

Jacques-François Duban (1797-1870) (likely a misspelling of Félix Duban), a French architect involved in significant restoration projects like the Louvre.

Paul Dubois (1829-1905), a French sculptor and painter, part of the "Florentine" group of French sculptors.

While direct collaborations or deep personal interactions between Douglas and all these figures are not extensively documented, their contemporaneous activity paints a picture of the rich artistic landscape of the 19th century. Douglas's focus on animal art, particularly in Britain, placed him in a popular and commercially viable niche, yet one that demanded considerable skill and sensitivity to succeed.

Personal Life: Glimpses Beyond the Canvas

While much of the historical record focuses on an artist's public career and works, glimpses into Edwin Douglas's personal life provide a more rounded picture. He was born in Edinburgh, and his Scottish identity remained a part of his artistic output throughout his life.

In 1872, Douglas purchased and renovated a house in West Coster (likely a misspelling or a very local name, perhaps referring to a district or a specific property whose name has changed). This indicates a degree of early success and a desire to establish a comfortable home base.

A significant development in his personal life occurred around his move to England. He married Maria Greathurst. An interesting detail is that Maria had previously been employed as a maid in the household of the Duke of Westminster, one of the wealthiest and most influential aristocratic families in Britain. This connection, however tangential, hints at the social strata that artists sometimes moved within or aspired to. The couple settled in Ornan Gosforth, Northumberland, England, by 1874. They had a daughter, Clare H. Douglas, born in 1875. This domestic stability likely provided a supportive backdrop for his artistic endeavors.

His later residences in Dorking and Shere, Surrey, suggest a preference for the picturesque English countryside, which would have been conducive to his study of animals and rural scenes, while still allowing access to the London art market. These details, though sparse, paint a picture of a family man who achieved a comfortable, professional life through his artistic talents.

Later Career, Enduring Appeal, and Legacy

Edwin Douglas continued to paint and exhibit into the early 20th century, with his last Royal Academy exhibitions occurring around 1900. His style, while rooted in Victorian realism, maintained its appeal due to the timeless subject matter of animals and the evident affection and skill with which he portrayed them. The Victorian era had seen an explosion in pet ownership, the formalization of dog breeds through kennel clubs and shows, and a general romanticization of nature and rural life. Douglas's art tapped directly into these societal trends.

His paintings, particularly those of dogs, were not just aesthetically pleasing; they often captured the specific characteristics of breeds that were gaining popularity, from sporting dogs to lapdogs. This made his work desirable to a wide range of patrons, including landowners, sporting enthusiasts, and the growing number of middle-class families who cherished their animal companions. The emotional and sometimes anthropomorphic qualities he imparted to his subjects resonated deeply, making his animals relatable and endearing.

The legacy of Edwin Douglas is that of a highly skilled and sensitive animalier painter who made a significant contribution to this genre within British art. While perhaps not achieving the same level of overarching fame as Landseer or some of his more avant-garde contemporaries who were pushing the boundaries of art into modernism, Douglas excelled within his chosen field. His works are held in various public and private collections and continue to be appreciated for their technical accomplishment, their charm, and their affectionate portrayal of the animal kingdom. He remains a notable figure for those interested in Victorian art, Scottish art, and the history of animal painting. His dedication to capturing the essence of his animal subjects ensures his enduring relevance.

Historical Context: Art, Animals, and Victorian Society

To fully appreciate Edwin Douglas's work, it's essential to consider the historical and cultural context of Victorian Britain. The 19th century witnessed profound societal changes, including industrialization, urbanization, and the rise of the middle class. Paradoxically, as society became more urbanized, there was often a corresponding romanticization of nature, the countryside, and animals.

Animals played a multifaceted role in Victorian life and imagination. They were companions, working partners, subjects of scientific study, and symbols in art and literature. The rise of the Kennel Club (founded in 1873) and the proliferation of dog shows reflected a growing, systematized interest in dog breeds. Queen Victoria herself was a devoted dog lover, which further popularized canine companionship among all classes. Douglas's focus on dogs, therefore, was perfectly attuned to the spirit of the age.

Sporting art, depicting hunting, racing, and other field sports, also had a long and distinguished tradition in Britain, with artists like George Stubbs (1724-1806) in the previous century setting a high bar for equine and animal anatomy. Douglas's scenes of hunting and sporting dogs continued this tradition, appealing to a clientele that valued these pursuits.

Furthermore, Victorian art often carried a strong narrative or moral component. Even in animal paintings, there could be underlying themes of loyalty (as in a faithful dog), courage (a stag at bay), or innocence (a child with a pet). Douglas's ability to imbue his animal subjects with personality and to place them in suggestive narrative contexts contributed significantly to their popularity. His realism, combined with a touch of sentiment, struck the right chord with Victorian audiences who valued both verisimilitude and emotional engagement. The comparison to Edgar Degas (1834-1917), a French Impressionist known for his studies of movement, particularly in horses and dancers, is interesting. While stylistically very different, both artists shared a keen interest in capturing the dynamic essence and anatomical truth of their subjects.

Conclusion: An Enduring Affection for the Animal World

Edwin Douglas passed away in 1914, at the cusp of a new era that would see artistic styles and societal values transform dramatically. Yet, his body of work remains a charming and skillful testament to a particular period in British art history and to an enduring human fascination with the animal kingdom. As a Scottish artist who found success in the wider British art world, he specialized in a genre that brought joy and recognition, particularly through his sensitive and lifelike portrayals of dogs.

His paintings, from the regal A Cavalier King Charles Spaniel to the evocative The Deer-Path and the action-filled The 12th of August, showcase a consistent dedication to his craft and a genuine empathy for his subjects. Influenced by the great Sir Edwin Landseer and working alongside a host of talented contemporaries, Douglas carved out his own niche. He provided Victorian society with images that reflected their love for animals, their appreciation for the natural world, and their fondness for narrative and sentiment in art. Today, Edwin Douglas is remembered as a fine animalier, an artist whose canvases continue to delight and to offer a window into the artistic sensibilities of the Victorian age. His contribution to animal painting, especially his canine portraits, ensures his place as a respected figure in British art.