Introduction: A Beacon in Belgian Art

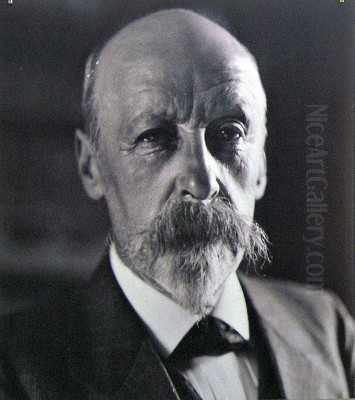

Emile Claus stands as a towering figure in the landscape of Belgian art, celebrated primarily as the leading force behind Luminism, a distinct strand of Impressionism that flourished in the country around the turn of the 20th century. Born on September 27, 1849, in Sint-Eloois-Vijve, a village in West Flanders, Belgium, and passing away on June 14, 1924, in Astene, Claus dedicated his life to capturing the ephemeral effects of light, particularly within the familiar landscapes of his homeland. His journey from academic realism to a vibrant, light-filled Impressionist style cemented his reputation as one of Belgium's most significant painters, often affectionately dubbed the "Prince of Light." His work not only reflected international artistic currents but also forged a unique path, influencing generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Emile Claus's origins were humble. Born into a large family, his father worked as a grocer and later a lock-keeper. From a young age, Claus displayed an undeniable passion for drawing and painting. This nascent talent was nurtured through sheer determination; it's recounted that as a boy, he would diligently walk three kilometers each week to the nearby town of Waregem to attend drawing classes at the local academy. This dedication flew in the face of his father's practical aspirations for him – a career as a baker seemed a more secure path than the uncertain life of an artist.

Undeterred by familial expectations, the young Claus sought support for his artistic ambitions. In a move demonstrating remarkable resolve, he wrote a letter to the renowned Belgian composer Peter Benoit, seeking assistance. Benoit, recognizing the young man's potential or perhaps moved by his plea, intervened. This support proved crucial, paving the way for Claus to leave his rural beginnings and enroll at the prestigious Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts around 1869. This step marked the formal beginning of his artistic education and his departure from the path his father had envisioned.

Academic Foundations in Antwerp

At the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts, Emile Claus received a thorough grounding in the academic traditions of the time. He studied under the tutelage of Jacob Jacobs, a landscape painter, and more significantly, Nicaise de Keyser, a prominent history and portrait painter and the director of the Academy. Under de Keyser's guidance, Claus mastered the techniques of academic realism, focusing on precise drawing, conventional composition, and a relatively somber palette typical of the era's official art.

His early works reflect this training, often depicting portraits and realistic genre scenes with a social undertone. He achieved considerable success with these early realist paintings, gaining recognition in official Salons. Works from this period demonstrate technical skill and an eye for detail, but they lack the vibrant light and colour that would later define his oeuvre. Figures like Henri Leys and Charles Verlat were also influential figures in the Antwerp art scene at the time, contributing to the prevailing artistic climate Claus initially navigated.

Travels and the Turn Towards Light

Although initially successful within the academic framework, Claus felt the pull of new artistic developments emerging elsewhere in Europe, particularly in France. Starting in the 1880s, frequent trips to Paris exposed him directly to the revolutionary works of the French Impressionists. He encountered the paintings of Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, artists who prioritized capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and employed a brighter palette with broken brushwork.

This exposure was transformative. Claus began to experiment, gradually abandoning the darker tones and tightly rendered forms of his academic training. He started incorporating lighter colours, exploring the play of sunlight and shadow, and adopting a looser, more suggestive brushstroke. While he never fully adopted the spontaneous, sketch-like quality of some French Impressionists, their emphasis on observing nature directly and rendering the sensations of light profoundly altered his artistic direction. Travels to Spain, Morocco, and the Netherlands during these years also likely broadened his visual experience, further contributing to his evolving style.

Astene: The Sanctuary of Sunshine

A pivotal moment in Claus's life and career came in 1883 when he purchased a cottage named "Zonneschijn" (Sunshine) in the serene village of Astene, situated along the picturesque banks of the River Leie (Lys) near Deinze. This location would become inextricably linked with his artistic identity. The gentle landscapes of the Leie region, with its meandering river, lush fields, poplar trees, and rural life, provided him with endless inspiration. It was here, immersed in the familiar beauty of his native Flanders, that his unique style truly blossomed.

"Zonneschijn" became his home, his studio, and a gathering place for fellow artists and writers. The consistent presence of the river and the changing light upon its waters and surrounding fields became the central motif of his work for decades. He tirelessly studied the effects of sunlight at different times of day and during various seasons, translating his observations onto canvas with an increasingly vibrant and luminous palette. Astene was not just a location; it was the crucible where Emile Claus forged his signature Luminist style.

Belgian Luminism: A Radiant Vision

Emile Claus is considered the foremost proponent of Belgian Luminism. While related to French Impressionism in its focus on light and contemporary life, Luminism, as practiced by Claus and his followers, often pushed the intensity of light and colour further. It wasn't merely about capturing a fleeting atmospheric effect, but about conveying the almost spiritual or life-giving force of sunlight itself. Claus achieved this through the use of pure, bright colours, often applied in small dabs or strokes, reminiscent of Pointillism but used more freely to create shimmering textures and dazzling light effects.

His Luminist works are characterized by vibrant palettes, often featuring blues, violets, and oranges in the shadows instead of traditional grays or blacks, and brilliant yellows, pinks, and whites in sunlit areas. He masterfully depicted reflections on water, the dappled light filtering through leaves, and the radiant glow of sun-drenched fields. Unlike the sometimes melancholic undertones found in the work of some contemporaries, Claus's Luminism generally exudes optimism, celebrating the beauty and vitality of nature and rural existence under the benevolent gaze of the sun.

Masterpiece: The Beet Harvest (1890)

The Beet Harvest (De Bietenoogst), painted in 1890, is widely regarded as a seminal work in Claus's transition towards Luminism and one of his most important paintings. Currently housed in the Museum van Deinze en de Leiestreek (Mudel), this large canvas depicts farmers harvesting sugar beets in a field under the soft glow of the afternoon sun. While still retaining a degree of realistic detail in the figures and landscape, the painting is notable for its heightened sensitivity to light and colour.

Claus employs a brighter palette than in his earlier works, capturing the warm sunlight illuminating the scene and casting soft, coloured shadows. The composition is dynamic, showing the labourers engaged in their task, connecting the human element to the rhythms of the land. The Beet Harvest marks a significant step away from academic conventions, showcasing Claus's growing confidence in rendering the atmospheric effects of light and his deep connection to the agrarian life of the Leie region. It signaled the arrival of a powerful new voice in Belgian painting.

Masterpiece: Ice Birds (1891)

Following closely on The Beet Harvest, Ice Birds (IJsvogels), painted in 1891, further solidified Claus's move towards a fully realized Luminist style. This work captures a winter scene, likely along the River Leie, where small birds, possibly kingfishers (ijsvogels in Dutch), are perched or flitting near the icy water's edge. The painting is a brilliant study in the effects of cold, clear winter light on snow and ice.

Claus uses a palette dominated by blues, whites, and violets, skillfully rendering the crisp atmosphere and the reflective qualities of the frozen landscape. The application of paint is looser, with visible brushstrokes contributing to the shimmering effect of light on the snow. Ice Birds demonstrates Claus's ability to find beauty and vibrant light even in the starkness of winter, showcasing his mastery in capturing diverse atmospheric conditions through his evolving Luminist technique. It stands as another key example of his mature style emerging in the early 1890s.

Masterpiece: Cows Crossing the Lys (c. 1899)

Cows Crossing the Lys (Koeien over de Leie), often dated around 1899, is one of Claus's most iconic and celebrated paintings depicting his beloved River Leie. The work shows a herd of cows wading across the river, their forms reflected in the sunlit water. This painting is a quintessential example of Claus's Luminism at its peak. The play of light on the water's surface is rendered with dazzling virtuosity, using myriad dabs of colour – blues, greens, yellows, pinks – to convey the shimmering, moving reflections and the warmth of the sun.

The composition is simple yet powerful, focusing on the harmonious relationship between the animals and the riverine landscape. The atmosphere is one of tranquil, sun-drenched rural life. First exhibited to great acclaim, the painting was acquired by the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, where it remains a highlight of the collection. It perfectly encapsulates Claus's fascination with the Leie and his extraordinary ability to translate the vibrant effects of sunlight into paint. Its enduring popularity speaks to its success in capturing the idyllic essence of the region.

Vie et Lumière: Spreading the Light

Emile Claus was not only a practitioner but also a promoter of Luminism. In 1904, he played a key role in founding the artistic circle "Vie et Lumière" (Life and Light). This group brought together artists who shared an interest in exploring the effects of light and colour in their work, effectively becoming the main platform for Belgian Luminism. Claus served as the central figure and mentor within the group.

Members and associates included artists like Georges Buysse, a close friend who also painted the Leie landscapes, Anna De Weert (one of Claus's most prominent students), James Ensor (though more aligned with Symbolism and Expressionism, he exhibited with them initially), Georges Lemmen, and Théo van Rysselberghe (key figures in Belgian Neo-Impressionism whose pointillist techniques influenced Luminism). While stylistic approaches varied among members, the common thread was the emphasis on light as a primary subject. Vie et Lumière held regular exhibitions, helping to disseminate the Luminist aesthetic both within Belgium and internationally, solidifying Claus's position as a leader in the Belgian avant-garde of the time.

Mentorship and Artistic Circle

Beyond his own prolific output, Emile Claus was an influential teacher and mentor. His studio "Zonneschijn" in Astene became a hub attracting younger artists eager to learn from the master of light. He was known for his encouraging approach, particularly towards female artists, who often faced greater barriers in the art world.

His most famous student was arguably Jenny Montigny (1875-1937). She arrived in Astene in 1893 and developed a close, lifelong relationship with Claus, who was 26 years her senior. Their bond was both personal and professional; Montigny became a devoted follower of his Luminist style, though she developed her own distinct voice over time. Their relationship, while inspiring artistically, sometimes attracted comment or controversy. Other notable female artists who studied with Claus and achieved recognition include Anna De Weert, known for her paintings of her garden by the Leie, as well as artists like Clara Voorma and Gabrielle Huysseaux (later known as Gabrielle van der Schueren). Through his teaching, Claus directly shaped the next generation of Belgian Impressionist painters.

London Exile: The Thames in Fog and Light

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 forced Emile Claus to leave Belgium. Like many Belgian artists and intellectuals, he sought refuge in London, where he remained until the end of the war in 1918. This period of exile marked a distinct phase in his work. Separated from his beloved River Leie, he turned his attention to the urban landscape of London, particularly the River Thames.

He produced a remarkable series of paintings depicting the Thames and its iconic bridges – Waterloo Bridge, Charing Cross Bridge, Blackfriars Bridge – under various atmospheric conditions. These works capture the unique light of London, often diffused by fog or mist, contrasting with the clearer, brighter light of Flanders. His London paintings, such as Sunset on Waterloo Bridge (1916) or views of the Houses of Parliament, inevitably invite comparison with Claude Monet's earlier series of the same subjects. While perhaps less radically abstract than Monet's interpretations, Claus's London works are powerful studies of light, atmosphere, and reflection in an urban setting, demonstrating his adaptability and continued fascination with capturing luminous effects, even far from home. The influence of writer Camille Lemonnier, who had encouraged his focus on light years earlier, might be seen as resonating during this period of reflection and adaptation.

Return to Astene and Later Years

After the war ended in 1918, Emile Claus returned to his cherished home "Zonneschijn" in Astene. He resumed painting the familiar landscapes of the Leie region with renewed vigour, though some critics note a subtle shift or perhaps a consolidation of his style in his later works. He continued to be a respected figure in the Belgian art world, exhibiting his work and maintaining his influence.

His dedication to capturing the light and life of the Leie remained unwavering until his death. He passed away in Astene on June 14, 1924, at the age of 74. He was buried in his own garden at "Zonneschijn," a fitting final resting place for an artist so deeply connected to that specific patch of earth and its surrounding light. His death marked the end of an era for Belgian Luminism, but his legacy was firmly secured.

Recognition and Museum Presence

Throughout his career and posthumously, Emile Claus received significant recognition. He exhibited widely in Belgium and internationally, including Paris, Venice, and London, garnering awards and critical acclaim. The Belgian state and major museums acquired his works, recognizing their importance. Critic Emile Verhaeren was an early champion, praising the authenticity and depth of his art.

Today, his paintings are held in the collections of major Belgian museums, including the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, the Museum of Fine Arts (MSK) in Ghent, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), and importantly, the Museum van Deinze en de Leiestreek (Mudel) in Deinze, which holds a significant collection due to his strong ties to the region. His international reputation ensures his works also appear in collections and exhibitions abroad. The continued interest in his work testifies to his enduring appeal.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Emile Claus's influence on Belgian art was profound and lasting. As the leading figure of Luminism, he decisively shifted the direction of landscape painting in Belgium towards a brighter, more modern aesthetic, moving away from the darker tones of realism and the Hague School influence. He provided a Belgian counterpart to French Impressionism, rooted in local landscape and sensibility.

His direct influence is most evident in the work of his students, particularly Jenny Montigny and Anna De Weert, who continued to practice variations of the Luminist style. More broadly, his emphasis on light and colour, and his dedication to depicting the Flemish landscape, resonated with subsequent generations. While later movements like Flemish Expressionism, championed by artists such as Constant Permeke and Gustave De Smet (who were also associated with the Leie region, forming the 'Latem School'), took a radically different stylistic path emphasizing subjective emotion and form over light effects, Claus's work remained a significant reference point for landscape painting in Flanders. His legacy lies in his stunning body of work and his role in defining a key moment in Belgian art history.

Centenary Celebrations and Continued Relevance

The enduring significance of Emile Claus is highlighted by the numerous events organized in 2024 to commemorate the 175th anniversary of his birth and the 100th anniversary of his death. The city of Deinze and the Museum van Deinze en de Leiestreek (Mudel) declared 2024 the "Claus Year," hosting a major retrospective exhibition titled "Emile Claus: Prince of Light," featuring key works gathered from various collections, including loans from the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts.

Other initiatives included dedicated cycling and walking routes through the landscapes he painted, the issuing of commemorative stamps, and even a digital interactive exhibition in the church of his birth village, Sint-Eloois-Vijve, bringing his painting The Cockfight to life. These activities demonstrate that Claus's art continues to captivate audiences and inspire cultural engagement, confirming his status not just as a historical figure but as an artist whose vision of light and landscape remains relevant and cherished today. His ability to translate the beauty of his surroundings into canvases radiant with light ensures his place among the great European painters of his time.

Conclusion: An Enduring Light

Emile Claus remains a pivotal figure in the story of Belgian art. His journey from academic realism to becoming the "Prince of Light" and the chief exponent of Luminism charts a course of artistic discovery deeply intertwined with his love for the Flemish landscape, particularly the River Leie. Through works like The Beet Harvest, Ice Birds, and Cows Crossing the Lys, he captured the essence of his environment with an unparalleled sensitivity to the effects of sunlight. Founding Vie et Lumière and mentoring artists like Jenny Montigny and Anna De Weert, he actively shaped the artistic landscape around him. Even his wartime exile produced memorable works exploring the different light of London's Thames. Celebrated in his lifetime and commemorated extensively a century after his death, Emile Claus's luminous vision continues to shine, securing his legacy as a master painter who truly understood and conveyed the transcendent power of light.