Emilie Preyer stands as a significant figure in the realm of 19th-century German art, particularly celebrated for her exquisite still life paintings. Born into an artistic family, she carved out a distinguished career, achieving international recognition for her meticulous technique, her profound understanding of light and texture, and her ability to imbue everyday objects with a captivating sense of presence. Her work, while rooted in the traditions of the Düsseldorf School of Painting, possesses a unique charm and technical brilliance that continues to appeal to collectors and art enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Düsseldorf

Emilie Preyer was born on June 6, 1849, in Düsseldorf, Germany, a city that was then a vibrant hub of artistic activity. Her destiny as a painter seemed almost preordained, as she was the daughter of Johann Wilhelm Preyer, one of the most respected still life painters of the Düsseldorf School. From a young age, Emilie was immersed in an environment where art was not just a profession but a way of life. Her father's studio was her first classroom, and his meticulous approach to painting became her earliest and most profound influence.

During this period, opportunities for formal artistic training for women were severely limited. The prestigious Düsseldorf Royal Academy of Arts, like many similar institutions across Europe, did not admit female students. This societal barrier, however, did not deter Emilie. She became an informal, yet dedicated, student of her father. Under his expert tutelage, she honed her observational skills and mastered the foundational techniques of drawing and oil painting, focusing intently on the genre that would define her career: still life.

Beyond her father's direct instruction, Emilie also benefited from the broader artistic milieu of Düsseldorf. She reportedly took lessons from Heinrich Mücke, a painter known for his historical and narrative scenes, and Hans Fredrik Gude, a celebrated Norwegian landscape artist who was a prominent professor at the Düsseldorf Academy. While still life remained her primary focus, these diverse influences likely broadened her artistic understanding and perhaps subtly informed her compositional choices and appreciation for natural elements.

The Düsseldorf School of Painting: A Fertile Ground

To understand Emilie Preyer's artistic development, it is essential to consider the context of the Düsseldorf School of Painting. Active from the 1820s to the early 20th century, this influential school, centered around the Düsseldorf Royal Academy of Arts, was renowned for its emphasis on detailed realism, fine finish, and often, narrative or anecdotal content. While landscape painting, championed by artists like Andreas Achenbach, Oswald Achenbach, and Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, was a dominant genre, the school also produced exceptional artists in historical painting, such as Wilhelm von Schadow (the Academy's director for a period) and Carl Friedrich Lessing, as well as genre painters like Ludwig Knaus and Benjamin Vautier.

Johann Wilhelm Preyer, Emilie's father, was a leading exponent of still life within this school. His works were characterized by their precise rendering of fruits, flowers, and tableware, often set against dark backgrounds, a technique that harked back to the Dutch Golden Age masters. He instilled in Emilie a deep respect for craftsmanship and an unwavering attention to detail. The Düsseldorf School's general ethos of meticulous observation and technical proficiency provided a supportive framework for Emilie's own artistic inclinations.

While she could not formally enroll, the spirit of the Academy and the city's artistic community undoubtedly shaped her. The emphasis on verisimilitude, the careful study of nature, and the high value placed on technical skill were all hallmarks of the Düsseldorf environment that resonated deeply in Emilie Preyer's artistic output. She absorbed these principles, internalizing them to develop her own distinct voice within the still life tradition.

Navigating a Male-Dominated Art World

Emilie Preyer's journey as an artist was undertaken in an era when the art world was overwhelmingly male-dominated. The societal expectations for women often confined them to domestic roles, and pursuing a professional career, especially in a field as competitive as art, was a formidable challenge. The lack of access to formal academic training was a significant hurdle, denying women artists the structured curriculum, life drawing classes, and networking opportunities available to their male counterparts.

Despite these obstacles, Emilie Preyer, through a combination of talent, determination, and the invaluable support of her father, managed to forge a successful career. Her informal apprenticeship under Johann Wilhelm Preyer provided her with a high-caliber education that, in many ways, rivaled what she might have received at the Academy, particularly in her chosen specialization. She learned not only the technical aspects of painting but also the discipline and dedication required to excel.

Her success was not an isolated case, but it was certainly exceptional. Other women artists of the 19th century, such as the French animal painter Rosa Bonheur or the Impressionists Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, also navigated these challenges in their respective contexts, often relying on private tuition, family connections, or sheer tenacity. For Emilie, her father's reputation undoubtedly opened some doors, but it was her own skill that earned her recognition and sustained her career. The fact that she achieved financial independence through her art was a remarkable feat for a woman of her time.

Artistic Style and Meticulous Technique

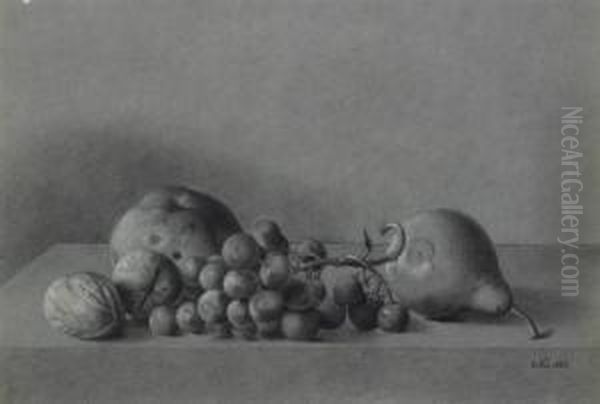

Emilie Preyer's artistic style is firmly rooted in realism, characterized by an extraordinary level of detail and a refined, almost polished, finish. She inherited her father's penchant for precision but developed her own nuanced approach to composition, light, and texture. Her canvases are typically small and intimate, drawing the viewer into a closely observed world of carefully arranged objects.

A hallmark of her technique is the incredibly fine brushwork, which leaves little to no visible trace, creating smooth, almost enamel-like surfaces. This meticulousness allowed her to render the varied textures of her subjects with astonishing fidelity: the velvety bloom on a peach, the taut, reflective skin of a grape, the cool smoothness of a porcelain dish, or the intricate facets of a wine glass. She paid close attention to the play of light, masterfully capturing reflections, highlights, and subtle gradations of shadow that give her subjects a three-dimensional, tangible quality.

Her compositions are typically well-balanced and harmonious. She often arranged fruits, nuts, and glassware on a stone ledge or a polished wooden tabletop, frequently against a neutral or subtly gradated dark background. This traditional staging, reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch masters like Willem Claesz. Heda or Pieter Claesz, served to emphasize the colors and forms of the objects themselves. The dark backgrounds, in particular, allowed the luminous qualities of the fruit and the sparkle of glass to come to the fore.

Key Themes and Signature Motifs

Fruit was undoubtedly Emilie Preyer's most favored subject. She depicted a rich variety of fruits with an almost scientific accuracy, yet imbued them with an undeniable aesthetic appeal. Peaches, plums, grapes (both green and dark), apricots, cherries, and berries feature prominently in her oeuvre. She often created a dynamic interplay of colors and forms by contrasting dark-hued fruits like plums and black grapes with lighter ones such as peaches, apricots, or green grapes. This not only added visual interest but also allowed her to showcase her skill in rendering different surface qualities.

Glassware was another recurring element in her still lifes. Wine glasses, sometimes filled with wine or champagne, or delicate glass bowls, provided an opportunity for Preyer to demonstrate her mastery in depicting transparency, reflection, and refraction. The way light interacts with glass – the subtle highlights on the rim, the distorted view of objects seen through it, the delicate sparkle – are all rendered with exquisite precision.

To add a touch of life and further enhance the realism of her scenes, Preyer frequently incorporated small details such as scattered nuts (walnuts and hazelnuts are common), fallen leaves, or even tiny insects. A dewdrop clinging to a grape, a ladybug crawling on a leaf, or a fly alighting on a piece of fruit are characteristic touches. These elements, often referred to as "trompe-l'œil" details, not only showcase her keen observational skills but also add a layer of narrative interest and a sense of immediacy to the compositions, inviting the viewer to look closer. The inclusion of insects, a motif also popular in Dutch Golden Age still lifes (for instance, in the works of Balthasar van der Ast, to whom her work has been compared), could also carry symbolic connotations of transience and the fleeting nature of beauty.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Throughout her prolific career, Emilie Preyer is estimated to have created around 250 paintings. While many share common themes and stylistic approaches, each is a testament to her focused dedication. Specific titles often highlight the primary subjects, such as:

Still Life with Fruit: A general title that could apply to many of her works, typically featuring a careful arrangement of various fruits, showcasing her skill in rendering textures and colors.

Still Life with Grapes, Peaches and Nuts: This title points to a common combination in her work. One can imagine a composition where the velvety skin of peaches contrasts with the translucent sheen of grapes and the rough texture of nutshells, all meticulously detailed.

Still Life with Fruit and Glass of Champagne: Such a work would highlight her ability to capture the effervescence of champagne and the delicate reflections on the glass, juxtaposed with the rich colors of accompanying fruit.

Still Life with Two Walnuts, Plums, Grapes, A Peach on a Branch and a Fly: This descriptive title, associated with a work auctioned at Dorotheum, paints a vivid picture of a classic Preyer composition – a small, intimate grouping, precise detail down to the individual hairs on a peach or the veins on a leaf, and the signature inclusion of an insect.

Still Life with Trauben, Reineclauden und Aprikosen auf Steinplatten (Still Life with Grapes, Greengages and Apricots on a Stone Ledge): This title, linked to a VAN HAM auction piece, suggests a typical setting on a cool stone surface, allowing for subtle reflections and a contrast with the warmth of the fruit colors.

In all these works, one would expect to find her characteristic precision, her subtle handling of light creating a gentle luminosity, and an overall sense of quiet elegance. The compositions are rarely cluttered; instead, each element is given space to be appreciated for its individual beauty and its contribution to the harmonious whole. Her ability to make these simple arrangements feel both timeless and intensely present is a key aspect of her enduring appeal.

International Recognition and Commercial Success

Emilie Preyer's talent did not go unnoticed. Her paintings gained popularity not only within Germany but also attracted an international clientele, particularly in the United States and other parts of Europe. American collectors, in particular, developed a fondness for the detailed realism of the Düsseldorf School, and Preyer's exquisite still lifes found a ready market. This international demand contributed significantly to her financial independence, a remarkable achievement for a female artist in the 19th century.

Her works were exhibited, and she managed her career with a degree of astuteness. The relatively small scale of her paintings made them suitable for domestic interiors, and their meticulous beauty appealed to the tastes of the burgeoning bourgeois collectors of the era. The consistency of her quality and the recognizable nature of her style helped build a strong reputation.

The prices her works commanded during her lifetime, and continue to command at auction today, attest to her sustained desirability. For instance, the mention of a work fetching a significant sum like $707,188 (as noted in the provided information, though the currency and specific sale details would need verification for precise art historical record) underscores the high regard in which her art is held. Such figures reflect not only the rarity and quality of her paintings but also her established place within the canon of 19th-century still life specialists.

Comparisons, Influences, and Artistic Lineage

Emilie Preyer's art is deeply indebted to the tradition of her father, Johann Wilhelm Preyer. She adopted his meticulous technique, his preference for fruit subjects, and his general compositional approach. However, it is widely acknowledged that Emilie was not merely an imitator. She developed her own distinct sensibility, often achieving a subtlety in the rendering of light and texture that some critics believe surpassed even her father's work. Her palette could be slightly brighter, and her arrangements, while always balanced, sometimes possessed a delicate airiness.

The broader influence of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish still life painting is undeniable in the work of both Preyers, and indeed, in much of the Düsseldorf School's still life output. Artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Willem Kalf, Rachel Ruysch (a highly successful female still life painter of the Dutch Golden Age), and Balthasar van der Ast set precedents for detailed realism, complex arrangements, and symbolic content in still life. Emilie Preyer's work shares with these masters a love for verisimilitude and an appreciation for the beauty of everyday objects. The comparison to Balthasar van der Ast, noted for his delicate renderings of fruit, flowers, and insects, is particularly apt.

While firmly within the realist tradition, her work stands apart from, for example, the broader, more painterly still lifes of French contemporaries like Henri Fantin-Latour, or the revolutionary approaches to form and color being explored by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists during the later part of her career. Preyer remained committed to the detailed, illusionistic style she had mastered, perfecting it within its own parameters rather than seeking radical innovation in the manner of Paul Cézanne, whose still lifes were transforming the genre.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Emilie Preyer continued to live and work in Düsseldorf throughout her life. She remained dedicated to her art, producing a consistent body of high-quality still lifes. She passed away on September 23, 1930, at the age of 81, leaving behind a legacy as one of Germany's foremost female painters of the 19th century and a master of the still life genre.

Her paintings are held in private collections and museums, and they continue to be sought after at auctions, where they command strong prices. Publications such as the book Weiß & Paffrath: Johann Wilhelm Preyer und Emilie (2009) and inclusions in catalogues like KALLMORGEN – DRAWINGS, PRINTS & PAINTINGS help to document and celebrate her contributions to art history.

The enduring appeal of Emilie Preyer's work lies in its timeless beauty and technical perfection. In a world increasingly dominated by rapid change and fleeting images, her paintings offer a moment of quiet contemplation, a celebration of the simple, tangible beauty of the natural world, rendered with a skill that inspires admiration. Her success as a woman artist in a challenging era also serves as an important historical marker.

Emilie Preyer in Art Historical Context

Emilie Preyer occupies a respected niche within 19th-century European art. As a prominent member of the later phase of the Düsseldorf School, she upheld its traditions of realism and meticulous craftsmanship. While the avant-garde movements of Paris, such as Impressionism (with artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas) and later Post-Impressionism (Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin), were challenging academic conventions, artists like Preyer continued to find appreciation for finely wrought, illusionistic painting.

Her specialization in still life places her in a long lineage of artists dedicated to this genre. From the opulent "pronk" still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age to the more austere compositions of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin in 18th-century France, still life has offered artists a unique vehicle for exploring form, color, light, and texture. Emilie Preyer contributed to this tradition with a distinctly German precision and a quiet, understated elegance.

Her work, alongside that of her father, represents a high point of still life painting within the Düsseldorf School. While other German artists of the period, such as Adolph Menzel, were exploring different facets of realism, or Max Liebermann was engaging with Impressionism, Preyer remained steadfast in her chosen path, perfecting a highly polished and detailed style that resonated with collectors who valued technical virtuosity and serene beauty.

Conclusion: The Quiet Brilliance of Emilie Preyer

Emilie Preyer's artistic journey is a testament to her exceptional talent, her unwavering dedication, and her ability to thrive in a demanding artistic environment. Born into the legacy of the Düsseldorf School and guided by her accomplished father, Johann Wilhelm Preyer, she not only mastered the intricate art of still life but also infused it with her own delicate sensibility. Her paintings, characterized by their meticulous detail, luminous portrayal of light, and harmonious compositions, capture the transient beauty of fruits, flowers, and finely crafted objects with an almost magical realism.

Her international success and financial independence were remarkable achievements for a woman artist in the 19th century, underscoring the universal appeal of her exquisite craftsmanship. Today, Emilie Preyer's works continue to be cherished for their quiet elegance and technical brilliance, securing her place as a distinguished master of still life and an important figure in the history of German art. Her legacy endures in the delicate dewdrops, the velvety bloom of a peach, and the silent, luminous stories told on her canvases.