Marguerite Gérard stands as a significant figure in French art during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born in Grasse on January 28, 1761, and passing away in Paris on May 18, 1837, her life spanned a tumultuous period in French history, witnessing the final flourish of the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, the Napoleonic era, and the Bourbon Restoration. Despite the societal constraints placed upon women artists of her time, Gérard carved out a remarkably successful and independent career, celebrated for her exquisite genre scenes, portraits, and prints, primarily executed in a refined Rococo style blended with emerging Romantic sensibilities. Her close association with her brother-in-law, the famed Rococo master Jean-Honoré Fragonard, was pivotal to her development, yet she forged a distinct artistic identity admired for its technical precision, intimate charm, and insightful portrayal of domestic life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in the Fragonard Circle

Marguerite Gérard's journey into the art world began not through formal academic channels, but within the vibrant artistic environment of her own family. Born the daughter of Marie Gilette and Claude Gérard, a perfumer in the southern French town of Grasse, her early life took a decisive turn following her mother's death. Around the age of eight or soon after, she moved to Paris to live with her older sister, Marie-Anne Gérard, who had married the already renowned painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

This move placed the young Marguerite directly into the heart of the Parisian art scene. The Fragonard household, which was granted lodgings in the Louvre Palace – a privilege accorded to prominent artists – became her home and her first art school. Living and working alongside Fragonard, one of the most brilliant exponents of the late Rococo, provided her with unparalleled, albeit informal, training. Fragonard recognized her talent and took her under his wing, instructing her in the fundamentals of drawing, painting, and etching.

The Louvre itself, teeming with artists and filled with masterpieces, served as an extended classroom. Gérard absorbed the artistic currents of the time, learning not only from Fragonard's dynamic brushwork and lighthearted themes but also likely studying the works of Old Masters housed within the palace walls. Her sister Marie-Anne, also a painter (though less famous, specializing in miniatures), likely contributed to her early education. This immersive, familial apprenticeship shaped her technical skills and artistic outlook profoundly.

Artistic Style: Rococo Sensibilities and Dutch Precision

Marguerite Gérard developed a style that, while clearly indebted to the Rococo aesthetics embodied by her mentor Fragonard, possessed its own distinct characteristics. She embraced the Rococo penchant for intimacy, elegance, and the depiction of private life, often focusing on quiet domestic moments rather than the overtly playful or mythological scenes sometimes favored by Fragonard. Her color palette was typically soft and harmonious, and her compositions exuded a sense of calm and refinement.

However, Gérard distinguished her work through a meticulous technique and a remarkable attention to detail that drew comparisons to 17th-century Dutch Golden Age masters. Artists like Gabriel Metsu, Gerard ter Borch, and Gerrit Dou, known for their fijnschilder (fine painting) technique, specialized in small-scale genre scenes rendered with exquisite precision, capturing textures of fabrics, reflections on surfaces, and subtle plays of light. Gérard adopted this approach, painstakingly rendering the sheen of satin dresses, the warmth of polished wood, the softness of fur, and the delicate features of her subjects.

This fusion of French Rococo grace with Dutch meticulousness became her hallmark. While Fragonard's brushwork could be loose, energetic, and suggestive, Gérard's was typically tighter, more controlled, and descriptive. This precision lent her scenes of everyday life a heightened sense of realism and tangible presence, appealing strongly to the tastes of the rising bourgeoisie who appreciated depictions of comfortable domesticity and virtuous sentiment. Her handling of light was particularly adept, often using gentle, diffused illumination to create a serene and intimate atmosphere within her interiors.

Themes of Domesticity and Feminine Experience

The subject matter of Marguerite Gérard's art centered overwhelmingly on the private sphere, particularly the lives of women and children within comfortable domestic interiors. She excelled at capturing the quiet rhythms of household life: women engaged in needlework, reading letters, playing musical instruments (especially the piano or guitar), or tending to children. These scenes often convey a sense of tranquility, familial affection, and understated elegance.

Her depictions of motherhood are particularly noteworthy. Works like Nursing Mother (Mère allaitant) or paintings showing mothers guiding their children, such as The First Riding Lesson (in its painted or print versions), reflect contemporary Enlightenment ideas about education and maternal virtue, influenced perhaps by thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. However, Gérard avoids overt moralizing, focusing instead on the tender interactions and emotional bonds within the family unit. She portrays childhood with sensitivity, capturing moments of learning, playfulness, and sometimes, as in Wayward Child (L'Enfant capricieux), gentle discipline.

Animals, especially cats and dogs, frequently appear in her paintings, adding a touch of warmth and informality to the domestic setting. Her skill in rendering the soft fur and characteristic poses of cats became almost a signature element, perhaps another nod to Fragonard, who also included pets in his works. These animals are rarely mere accessories; they often interact with the human figures, enhancing the sense of intimacy and lived experience within the scene. Through these themes, Gérard offered a distinctly feminine perspective on the values and activities that defined the private lives of the upper-middle class in her era.

Navigating the Art World: Salon Success and Market Savvy

As a woman artist in late 18th and early 19th-century France, Marguerite Gérard faced significant institutional barriers. The prestigious Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, which controlled official artistic training and exhibition opportunities, admitted very few women. While contemporaries like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard achieved membership (though not without struggle), Gérard, perhaps due to her informal training or personal inclination, never joined the Académie.

Despite this, she achieved remarkable professional success. Following the French Revolution, the official Paris Salon exhibition was opened to all artists, regardless of Academic affiliation. Gérard began exhibiting regularly at the Salon from 1799 onwards, continuing for several decades. Her meticulously crafted genre scenes quickly found favor with critics and the public, earning her praise and prestigious awards, including a Gold Medal at the Salon of 1804 for The Clemency of Napoleon.

Gérard demonstrated considerable business acumen. Recognizing the growing market for smaller, domestically scaled paintings and the popularity of prints, she actively cultivated relationships with art dealers and print publishers. She produced etchings herself and also allowed skilled engravers to reproduce her paintings, making her work accessible to a wider audience and providing a steady source of income. This financial independence was unusual for women artists of the time and allowed her to maintain a successful studio practice throughout her long career, supporting herself entirely through her art. Her success served as an inspiration and demonstrated the viability of a professional artistic career for women outside the traditional academic structures.

Key Works and Collaborations

Marguerite Gérard's oeuvre consists of numerous paintings and prints, many of which exemplify her characteristic style and themes. Several works stand out as particularly representative:

L'Élève intéressante (The Interesting Student, c. 1786-90): Often considered a collaborative work with Fragonard, or heavily influenced by him, this painting depicts a young woman (possibly Gérard herself) intently studying, embodying themes of education and artistic dedication within an intimate setting. The detailed rendering of fabrics and objects is characteristic of Gérard's hand.

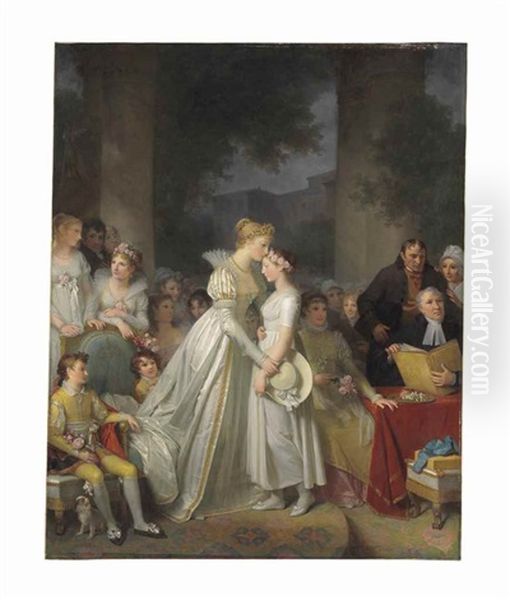

La Clémence de Napoléon (The Clemency of Napoleon, 1804): This historical genre scene, which won her a Gold Medal, depicts Napoleon pardoning the Princesse de Hatzfeldt. It showcases Gérard's ability to handle more complex compositions and official themes while retaining her focus on emotional nuance and detailed execution. It reflects her adaptation to the changing political and artistic climate of the Napoleonic era.

La Leçon de Musique (The Music Lesson) and La Leçon de Danse (The Dance Lesson): These recurring themes in her work allowed her to explore graceful interactions, often between mothers and daughters or teachers and pupils, within elegantly appointed interiors. A version of La Leçon de Danse, potentially a collaboration with Fragonard, is housed in the Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Portraits: While primarily known for genre scenes, Gérard was also an accomplished portraitist. Her Portrait of Madame Henri Gérard (her sister-in-law) and Portrait of a Young Girl (both in the Louvre) demonstrate her skill in capturing likeness and personality with sensitivity and refinement.

Prints: Gérard was involved in printmaking early in her career, collaborating with Fragonard on a series of etchings around 1778. She continued to produce and authorize prints after her paintings, such as The First Riding Lesson, which helped disseminate her popular compositions.

The exact nature of her collaboration with Fragonard remains a subject of discussion among art historians. While she began as his pupil and assistant, evidence suggests a more reciprocal partnership developed, particularly in the 1780s. Some works appear to be joint efforts, while others show his clear influence on her compositions or her contribution of detailed passages to his paintings. Regardless, their artistic dialogue was undoubtedly crucial to her development.

Interaction with Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Marguerite Gérard worked during a period of significant artistic transition. The dominant Rococo style, represented by masters like Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and her own mentor Fragonard, was being challenged by the rise of Neoclassicism, championed by Jacques-Louis David. Simultaneously, the sentimental genre scenes of Jean-Baptiste Greuze enjoyed immense popularity, and the foundations of Romanticism were being laid.

Gérard navigated this complex landscape adeptly. While her style remained rooted in Rococo intimacy and elegance, her meticulous realism and focus on virtuous domesticity resonated with Neoclassical ideals of clarity and moral seriousness, albeit expressed in a gentler, private key compared to David's grand historical narratives. Her work shares thematic ground with Greuze in its focus on family life and sentiment, though generally avoiding his overt melodrama.

Her detailed technique found kinship with the tradition of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, an earlier master of quiet still life and genre painting, admired for his humble subjects and profound observation. As a successful female artist, she was a contemporary of the celebrated portraitists Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. While their primary focus was portraiture, often on a grander scale, all three women navigated the male-dominated art world with skill and determination, achieving significant recognition.

Gérard's work can also be seen in dialogue with transitional figures like Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, whose style blended Neoclassical forms with a softer, more Romantic sensibility. While direct collaborative records with artists like David or Greuze are lacking, Gérard was undoubtedly aware of their work and positioned her own art within the broader artistic debates and trends of her time, finding a successful niche that appealed across stylistic divides. Her engagement with Dutch masters like Metsu and Ter Borch also placed her within a longer tradition of European genre painting. International contemporaries like the Swiss-born Neoclassical painter Angelica Kauffman also achieved fame during this period, highlighting the presence of successful women artists across Europe.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Marguerite Gérard continued to paint and exhibit well into the 19th century, adapting her style subtly over time but largely remaining true to her focus on intimate genre scenes. She maintained her financial independence and professional standing throughout her life, dying in Paris in 1837 at the age of 76. She never married and appears to have dedicated her life entirely to her art and her close familial ties, particularly with her sister and, initially, Fragonard.

Her legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, she represents a unique bridge between the late Rococo and early 19th-century genre painting. She refined the Rococo genre scene, infusing it with a level of detail and psychological nuance derived from Dutch traditions, creating works that were both elegant and relatable. Her focus on domesticity and the feminine sphere provided a valuable counterpoint to the grand historical and mythological subjects often favored by male contemporaries.

As a pioneering female artist, her long and successful career demonstrated that women could achieve professional recognition and financial independence through art, even without formal academic affiliation. She skillfully utilized the changing art market, leveraging printmaking and dealer relationships to build her reputation and livelihood.

For a period, like many Rococo artists, her work fell somewhat out of fashion with the dominance of later movements. However, renewed interest in 18th-century French art and the scholarly efforts to rediscover and re-evaluate the contributions of women artists have led to a greater appreciation of Marguerite Gérard's significant achievements. Her paintings are now held in major museums worldwide, including the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Hermitage Museum, and the National Gallery of Art, recognized for their technical brilliance, charming subject matter, and historical importance.

Conclusion

Marguerite Gérard remains a compelling figure in French art history. Emerging from the shadow of her famous brother-in-law, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, she established herself as a leading painter of genre scenes in her own right. Her distinctive style, blending Rococo elegance with Dutch precision, captured the intimate moments of domestic life with unparalleled delicacy and charm. Overcoming the limitations faced by women artists of her era, she achieved remarkable professional success and financial independence through talent, determination, and market savvy. Her work not only provides a fascinating window into the private world of late 18th and early 19th-century France but also stands as a testament to her individual artistic vision and her significant place within the broader narrative of European art.