Introduction: A Pioneer Across Waters

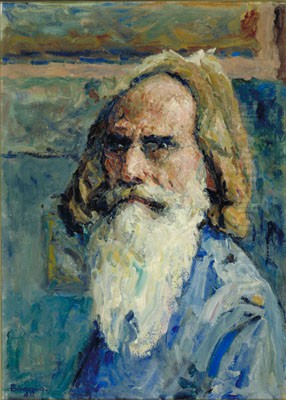

Emilio Boggio stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of Latin American art, particularly celebrated as a foundational force in Venezuelan Impressionism. Born in Caracas, Venezuela, on May 12, 1857, to an Italian merchant father and a mother of Viennese aristocratic heritage, Boggio's life and art embodied a transatlantic dialogue. His career unfolded primarily in France, the epicenter of the Impressionist revolution, yet his influence resonated profoundly back in his homeland. Boggio navigated the complex currents of late 19th and early 20th-century art, ultimately forging a path that helped transition Venezuelan painting from academic traditions towards a modern sensibility. His death on June 7, 1920, marked the end of a life dedicated to capturing light, color, and the nuances of the world around him.

Early Life and Formative Years

Boggio's early life was marked by movement and a blend of cultural influences inherent in his parentage. His family's background, combining Italian commercial enterprise with Viennese nobility, provided a complex tapestry from the start. In 1864, well before adolescence, he was sent to France for his education, studying at the prestigious Lycée Michelet in Paris until 1870. This early immersion in French culture would prove deeply influential.

His path took a brief detour when, at the age of sixteen, he returned to Venezuela, seemingly destined for a role in the family's business interests. However, the pull of art proved stronger than commerce. The seeds planted during his time in France began to germinate, leading him back to Paris in 1873. Though details of this period are less documented, it signifies a growing commitment to an artistic vocation over inherited commercial responsibilities. This dedication solidified with his definitive return to France in 1877, specifically to pursue formal art training.

Academic Training in Paris

Upon his return to Paris in 1877, Emilio Boggio enrolled in the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe, often serving as an alternative or supplement to the official École des Beaux-Arts. Crucially, he became a student of Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921). Laurens was a highly respected figure in the French art establishment, known primarily for his large-scale historical and religious paintings executed with academic precision and dramatic flair.

Studying under Laurens provided Boggio with a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and traditional painting techniques. While Boggio would ultimately embrace the looser brushwork and brighter palette of Impressionism, the discipline and structural understanding gained from Laurens likely remained an underlying element in his work. Laurens's own focus on historical and often somber themes might seem at odds with Boggio's later Impressionistic leanings, but the master's emphasis on narrative and human drama could have subtly informed Boggio's approach, even when applied to everyday scenes or landscapes.

The Embrace of Impressionism

Living and working in Paris during the late 1870s and 1880s placed Boggio directly in the vibrant, sometimes contentious, atmosphere surrounding Impressionism. While studying formally under Laurens, he could not have avoided exposure to the revolutionary works of artists who were challenging academic conventions. The Impressionist movement, spearheaded by figures like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), emphasized capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and scenes of modern life.

Boggio absorbed these influences profoundly. His subsequent work demonstrates a clear shift towards Impressionist concerns: a heightened sensitivity to light and its transient effects, the use of broken brushwork to convey texture and vibrancy, and a brighter, more varied color palette. He became particularly adept at rendering the interplay of light and shadow, a hallmark of the Impressionist approach. While he maintained connections to academic structures like the Salon, his stylistic evolution firmly placed him within the Impressionist orbit, making him one of the earliest Latin American artists to fully engage with this modern European movement.

Boggio's Distinctive Style: Impressionism with a Personal Touch

While deeply influenced by French Impressionism, Emilio Boggio developed a style that, while clearly related, retained a personal character. Often categorized as Post-Impressionist by some scholars due to the era and his individualistic application of techniques, his work consistently displays core Impressionist traits. He employed thick impasto, applying paint in visible, often energetic brushstrokes that gave texture and dynamism to his canvases. His palette was rich and vibrant, prioritizing the optical effects of color and light over strict adherence to local color.

However, Boggio's work sometimes incorporated a structural solidity or symbolic undertone less common in the purer forms of Impressionism practiced by Monet or Sisley. Snippets mention potential Symbolist elements, suggesting an interest beyond mere visual perception towards conveying mood or underlying meaning. Critics occasionally noted the "looseness" of his brushwork, which could be interpreted both as a sign of his modernity and, by more conservative viewers, as a departure from academic finish. Ultimately, Boggio synthesized Impressionist innovations with his own temperament and academic grounding, creating a style that was both contemporary and distinctly his own.

Key Themes and Subjects in Boggio's Art

Emilio Boggio's choice of subject matter reflects both his French environment and the broader concerns of Impressionism, often infused with a personal sensitivity. He frequently depicted landscapes, capturing the changing light and seasons in the French countryside. Works like Vaux-sur-Seine, le Gibet (1902) and Glaçons flottant sur l'Oise (1917) showcase his keen observation of nature and atmospheric effects, particularly the play of light on water and land.

Beyond landscapes, Boggio engaged with scenes of modern life, a central theme for many Impressionists. His painting End of Day (also referred to as El Trabajo or Labor in some contexts) portrays Parisian labor scenes, reflecting an interest in the working class and the rhythms of urban existence. This focus on labor aligns with the Realist traditions preceding Impressionism, exemplified by artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), but rendered with an Impressionist technique. He also explored more intimate, indoor scenes, as seen in his celebrated work Reading. This thematic range demonstrates an artist engaged with the visual and social realities of his time.

Masterwork: 'Reading' (La Lectura)

Among Emilio Boggio's most acclaimed works is Reading (La Lectura), painted in Paris in 1888. This painting is often cited as a pinnacle of his artistic achievement and a key example of his engagement with modern artistic principles. It garnered significant recognition early on, receiving an honorable mention at the prestigious Salon des Artistes Français in Paris in the year of its creation. This acknowledgment from the official art establishment, even as Impressionism was still solidifying its acceptance, highlights the quality and impact of the work.

Reading is celebrated for its masterful handling of light and color, particularly the way light filters into the depicted interior space, creating contrasts and illuminating the scene. The work emphasizes sensory experience, inviting the viewer to feel the quiet atmosphere and the texture of the environment. Art historians consider it a precursor to certain aspects of modern painting, showcasing Boggio's ability to synthesize Impressionist techniques with a compelling, intimate subject. Its success solidified Boggio's reputation in the competitive Parisian art world.

Other Notable Works and Recognition

Beyond Reading, several other works mark important points in Boggio's career. The painting depicting labor, often titled El Trabajo (Labor) or End of Day, is significant. There appears to be some conflation or multiple works addressing this theme, as sources mention El Trabajo winning a silver medal at a Paris Exposition (World's Fair), possibly distinct from the 1888 Salon mention for Reading. Regardless, his focus on the dignity and reality of labor, rendered with Impressionist flair, was a notable aspect of his oeuvre.

His landscape paintings remained a constant throughout his career. Vaux-sur-Seine, le Gibet (1902) and Glaçons flottant sur l'Oise (1917) are examples that demonstrate his continued exploration of light, atmosphere, and the specific character of the French landscape, particularly the areas around the Oise river where he eventually settled. These works showcase his mature style, characterized by confident brushwork and nuanced color harmonies, capturing specific moments in time and weather conditions.

Exhibitions and Professional Circles

Emilio Boggio actively participated in the Parisian art scene through exhibitions. His acceptance and honorable mention at the 1888 Salon des Artistes Français for Reading was a significant early success. Later in his career, he was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the influential Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. This gallery was known for handling major Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists, including Monet and Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), indicating Boggio's standing. The French critic Thiébault-Sisson wrote about this exhibition, analyzing Boggio's career and market presence.

His work continued to be exhibited posthumously. Odalys Art Gallery featured his work, particularly Reading, in exhibitions held in Caracas, Madrid, and Miami, underscoring his international relevance. He was also included in shows at El Círculo de Bellas Artes in Caracas. A notable, though posthumous, grouping occurred in a 1958 exhibition where his work was shown alongside that of Sam Mützner (1884-1959), a Romanian Post-Impressionist, and Nicolás Ferdinandov (1886-1925), a Russian-born artist active in Venezuela, suggesting thematic or stylistic connections perceived by curators later on. His association with collectors like Georges Petit further cemented his place within the art world infrastructure.

Connections and Contemporaries

Boggio's artistic journey connected him, directly or indirectly, with numerous figures. His teacher, Jean-Paul Laurens, provided his academic foundation. His style reveals the undeniable influence of Impressionists like Monet, Degas, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, whose work he would have seen extensively in Paris. He also fits within the broader Post-Impressionist landscape, alongside artists exploring subjective color and form, such as Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), who famously spent his last months in Auvers-sur-Oise, the same town where Boggio would later live and work. The Barbizon School painters, like Camille Corot (1796-1875), who emphasized landscape and light before the Impressionists, also form part of the artistic lineage Boggio inherited.

In the Venezuelan context, Boggio stands as a transitional figure. He followed a generation of highly skilled academic painters who also often trained in Europe, such as Martín Tovar y Tovar (1827-1902), the preeminent historical painter, and the talented triumvirate of Cristóbal Rojas (1857-1890), Arturo Michelena (1863-1898), and Antonio Herrera Toro (1857-1914). While Boggio shared their birth year with Rojas and Herrera Toro, his embrace of Impressionism set him apart stylistically. Perhaps his most significant connection in terms of direct influence was with his student, Armando Reverón (1889-1954), who became one of Venezuela's most important and unique modern artists, absorbing lessons about light and color from Boggio. The Venezuelan poet and diplomat Juan José Tablada also recognized Boggio's importance, drafting an unpublished biography.

Influence on Venezuelan Art

Emilio Boggio's primary importance lies in his role as a conduit for modern European art movements, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, into the Venezuelan art scene. While artists like Rojas and Michelena achieved great success with academic and realist styles, Boggio was among the very first Venezuelans to fully adopt and adapt the techniques and aesthetic principles of the French avant-garde. He demonstrated that Venezuelan artists could engage directly with the most current international art trends.

His return visits to Venezuela, though perhaps infrequent, and the eventual reception of his work there, helped to introduce these new ways of seeing and painting. His most direct legacy was through his influence on Armando Reverón. Reverón studied with Boggio and clearly absorbed his teacher's fascination with light and loose brushwork, though Reverón would take these elements in a highly personal, almost blindingly white, direction in his famous Macuto paintings. Boggio's work thus served as a crucial catalyst, helping to shift Venezuelan art away from its 19th-century academic roots and paving the way for the diverse modernist explorations of the 20th century. He remains recognized as a key promoter of Venezuelan modern art.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite his artistic achievements, Emilio Boggio's life and career were not without complexities and controversies. One significant point of contention, particularly viewed retrospectively, was his apparent support for Fascism later in his life. Sources indicate he openly admired the Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini and was even awarded an honor by the Italian King for propagating Fascist ideology. This political stance created a stark contrast with any earlier nationalist sentiments he might have held regarding Italy and raised questions about his allegiances, especially given his Venezuelan birth and French residency.

Professionally, his career faced fluctuations. The critic Thiébault-Sisson noted inconsistencies in Boggio's art market performance, suggesting his "adventurous" style and perhaps the economic disruptions caused by World War I impacted his commercial success. While he achieved recognition, it may not have been consistently stable. Furthermore, his Impressionist-derived style, particularly the "loose" brushwork, while innovative, could also attract criticism from those adhering to more traditional academic standards of finish. These factors, combined with the personal contradictions reflected in his political leanings, paint a picture of a talented artist navigating a challenging historical period.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Emilio Boggio spent much of his later life in France, eventually settling in Auvers-sur-Oise, a village near Paris famous for its association with artists like Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), Pissarro, and notably, Van Gogh. Boggio lived and worked there, continuing to paint the surrounding landscapes. His former home and studio in Auvers-sur-Oise have been preserved and recognized as a "Maison des illustres" (House of the Illustrious) by the French Ministry of Culture, serving as a site for exhibitions and preserving his memory in the place he spent his final years.

He passed away in Auvers-sur-Oise on June 7, 1920. Despite the controversies and market challenges he may have faced during his lifetime, his artistic legacy endured. His works are held in important collections in Venezuela and internationally, and they continue to be exhibited and studied. He is consistently acknowledged as a pioneer who brought European modernism into a Latin American context, significantly impacting the trajectory of Venezuelan art history. His paintings remain admired for their vibrant depiction of light, color, and life.

Conclusion: An Artist of Transition

Emilio Boggio occupies a unique and vital space in art history. As an Italian-Venezuelan artist trained in the heart of Paris, he became a crucial bridge between European artistic innovation and the developing modern art scene in Latin America. He absorbed the lessons of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, adapting them with a personal vision to depict landscapes, labor, and intimate moments. While navigating the complexities of academic expectations, market fluctuations, and controversial political affiliations, his dedication to his craft remained evident. Through his own work and his influence on subsequent generations, particularly Armando Reverón, Emilio Boggio left an indelible mark, forever recognized as a key figure in the modernization of Venezuelan art.