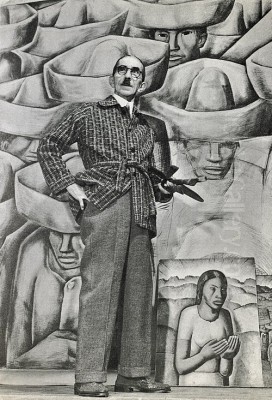

Alfredo Ramos Martínez stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Mexican art, often hailed as the "Father of Mexican Modernism." His life and career bridged continents and artistic movements, forging a unique path that blended European modernist techniques with a profound dedication to depicting the essence of Mexican culture and its people. Born in Mexico, educated both at home and in the vibrant art scene of early 20th-century Paris, and later settling in California, Ramos Martínez left an indelible mark not only through his paintings and murals but also as a revolutionary art educator.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Mexico

Alfredo Ramos Martínez was born in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico, in 1871. From a young age, his artistic talents were evident. His promise was recognized early, earning him a scholarship at the tender age of fourteen to study at the prestigious Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Academy of Fine Arts), also known as the Academy of San Carlos, in Mexico City. He studied there from approximately 1884 to 1892, distinguishing himself and winning multiple awards.

Despite his success within the Academy, Ramos Martínez grew dissatisfied with its rigid, traditional teaching methods. The institution heavily emphasized classical European styles and techniques, often relying on copying plaster casts. He found this approach stifling and lamented the Academy's disregard for the burgeoning Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements that were transforming art in Europe. One of his notable teachers during this period was Santiago Rebull, a respected master of the 19th-century Mexican academic tradition. However, Ramos Martínez yearned for a more direct, expressive approach to art-making.

A Fateful Encounter and European Horizons

A significant turning point came through an unexpected opportunity. In 1899, Ramos Martínez was commissioned to create a set of hand-painted menus for a dinner hosted by Mexican President Porfirio Díaz. His exquisite work caught the eye of Phoebe Apperson Hearst, the American philanthropist and mother of publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst, who was a guest at the event. Impressed by his talent, Hearst offered to sponsor his further studies in Europe.

This generous patronage enabled Ramos Martínez to travel to Paris around the turn of the century, immersing himself in the epicenter of the art world. This move would prove crucial in shaping his artistic development, exposing him firsthand to the revolutionary ideas and styles that he had previously only known from afar.

Paris: Immersion in Modernism

Arriving in Paris, Ramos Martínez eagerly absorbed the influences of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Symbolism. He studied the works of masters and contemporaries, learning from their innovative approaches to light, color, form, and subject matter. He spent time studying with French painters and was associated with the Barbizon School's emphasis on landscape painting directly from nature.

His time in Paris was marked by significant artistic growth and networking. He reportedly met and interacted with leading figures of the era, including Impressionist master Claude Monet and the young, revolutionary artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. These encounters, along with the general artistic ferment of Paris, profoundly influenced his evolving style. He also formed a deep and lasting friendship with the celebrated Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío, a leading voice of Modernismo in literature, whose ideas about artistic freedom likely resonated with Ramos Martínez.

Early Success Abroad

Ramos Martínez's talent quickly gained recognition in the competitive Parisian art scene. He began exhibiting his work, and a major breakthrough occurred in 1906 when his painting La Primavera (Spring) received an award at the prestigious Salon d'Automne. This accolade helped establish his reputation, and he became a successful portrait painter, sought after by European clientele.

His European period was characterized by an exploration of the styles he encountered, particularly the bright palettes and broken brushwork of Impressionism and the expressive forms and symbolic content of Post-Impressionism, potentially drawing inspiration from artists like Paul Gauguin. However, even while absorbing these European influences, the seeds of his later focus on Mexican identity were being sown.

Return to Mexico: A Catalyst for Change

After over a decade in Europe, Ramos Martínez returned to Mexico around 1910, arriving amidst the social and political upheaval of the Mexican Revolution. In 1913, a significant professional milestone occurred when he was appointed Director of the National Academy of Fine Arts – the very institution whose methods he had previously questioned.

This position provided him with a platform to implement radical changes in Mexican art education. He was determined to break away from the outdated academicism that still dominated the Academy and to foster a truly modern and authentically Mexican art.

The Open-Air Schools: Revolutionizing Art Education

The most significant contribution Ramos Martínez made as an educator was the establishment of the Escuelas de Pintura al Aire Libre (Open-Air Schools of Painting). The first of these schools was founded in the Santa Anita Iztapalapa area of Mexico City. This initiative was revolutionary for its time. It rejected the confines of the traditional studio and the reliance on copying plaster casts and European models.

Instead, Ramos Martínez encouraged students to work outdoors, directly observing and capturing the Mexican landscape, the quality of natural light, and the daily lives of ordinary people. The philosophy emphasized freedom of expression, individual inclination, and the importance of finding inspiration in one's own environment and cultural heritage. Furthermore, the schools aimed to be democratic, offering art education opportunities to students from all social classes, not just the elite.

Nurturing a Generation

The Open-Air Schools had a profound and lasting impact on the development of Mexican art. They fostered a spirit of experimentation and national pride, encouraging artists to develop styles that reflected Mexican realities. Ramos Martínez's pedagogical approach nurtured the talents of a generation of artists who would become central figures in the Mexican Mural Renaissance and beyond.

Among his most notable students who passed through the Open-Air Schools were David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and Rufino Tamayo. These artists, while developing their own distinct and powerful styles, were initially influenced by Ramos Martínez's emphasis on national themes and modernist experimentation. His educational reforms helped lay the groundwork for the flourishing of Mexican art in the decades that followed.

Defining a Style: European Techniques, Mexican Soul

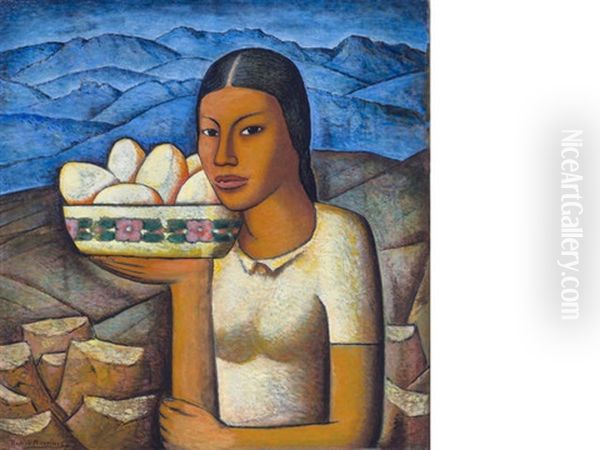

As an artist, Ramos Martínez developed a distinctive style that synthesized his European training with his deep connection to his homeland. His work is characterized by its bold, graphic quality, often featuring strong outlines and simplified forms. He employed rich, vibrant colors, sometimes applied with thick, expressive brushstrokes, creating surfaces imbued with texture and emotion.

His compositions often possess a sense of monumentality and dignity, even when depicting humble subjects. He masterfully blended elements of Impressionist light and color, Post-Impressionist structure and symbolism, and a unique aesthetic sensibility rooted in Mexican folk art and pre-Hispanic traditions. This fusion resulted in a style that was both modern and deeply "Mexicanized."

Themes of Dignity and Daily Life

Ramos Martínez's subject matter consistently revolved around Mexico and its people. He turned his attention away from European themes and academic conventions to focus on the figures and landscapes of his native land. He frequently depicted indigenous peoples, particularly women, often shown with stoic dignity and adorned with traditional clothing and flowers.

Peasants, laborers, flower vendors (vendedoras de flores), mothers and children, and bustling market scenes were recurrent themes. Through these subjects, he aimed to capture the spirit, resilience, and cultural richness of Mexico. His portrayals are often idealized and imbued with a sense of timelessness and grace, celebrating the connection between the people and the land.

Masterworks: Murals and Easel Paintings

Alfredo Ramos Martínez created a significant body of work across various media, including easel paintings, drawings, and murals. Several works stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns. La Primavera, the painting that won him acclaim in Paris, showcased his early mastery.

Later works further defined his mature style. Mujeres con frutas (Women with Fruit) exemplifies his focus on indigenous women, rendered with characteristic bold lines and vibrant colors. His murals, such as El Día del Mercado (Market Day), capture the energy and dynamism of Mexican life through complex compositions and rich detail. Canasta de Flores (Flower Basket) is another iconic theme, often featuring women bearing large baskets laden with colorful blooms.

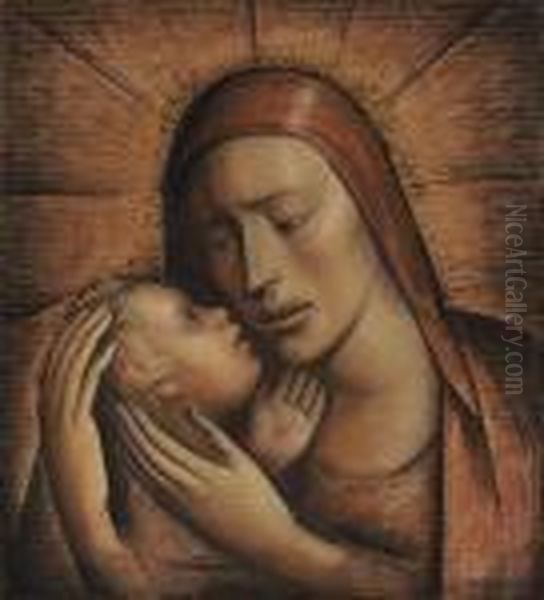

His painting La Malinche, depicting the complex historical figure, was featured in a major exhibition at the Denver Art Museum, highlighting its cultural significance. He also undertook religious commissions, creating murals that blended modernist aesthetics with spiritual themes, notably in California.

The California Chapter

In the late 1920s (around 1929 or 1931, sources vary slightly), Ramos Martínez and his family made a significant life change, relocating to Los Angeles, California. The primary motivation for this move was to seek specialized medical care for their daughter, Maria, who suffered from a debilitating bone disease.

This move marked the final phase of his artistic career. In California, he continued to paint prolifically, finding new inspiration in the landscapes and the lives of the Mexican and Mexican-American communities of Southern California. He adapted his style, sometimes working with different media and techniques, but his focus on Mexican themes remained central.

Murals in the United States

During his time in California, Ramos Martínez received several important commissions for murals, allowing him to work on the larger scale that suited his monumental style. He created murals for private residences, public buildings, and institutions. One notable project was a series of frescoes for the Margaret Fowler Memorial Garden at Scripps College in Claremont, California. Although he was unable to fully complete this ambitious cycle due to failing health, the existing portions and preparatory drawings are considered major works of his California period.

He also created religious murals, including works for the Chapel of Saint Anne at the Church of Our Lady Queen of the Angels in downtown Los Angeles, demonstrating his ability to adapt his style to devotional contexts while retaining his modernist sensibilities. These works contributed significantly to the art scene in Southern California.

Navigating the Art World: Contemporaries and Comparisons

Alfredo Ramos Martínez occupied a unique position within the landscape of 20th-century Mexican art. He was a contemporary of the famed "Tres Grandes" (Three Greats) of Mexican Muralism: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. While he interacted with them and even taught Siqueiros and Rivera, his artistic path diverged in significant ways.

He is undeniably a foundational figure, a pioneer who introduced modernism to Mexico and championed national themes before the mural movement fully coalesced. However, his work is often characterized as more lyrical, decorative, and idealized compared to the overtly political and often confrontational art of the muralists. While they focused heavily on revolution, history, and social struggle, Ramos Martínez often emphasized the beauty, dignity, and timeless aspects of Mexican culture and daily life. This difference in focus sometimes led to his work being somewhat overshadowed by the monumental public statements of the muralists, though his influence, particularly through education, was profound.

His network also included figures beyond Mexico, such as his early friendship with Rubén Darío and his encounters with European giants like Monet and Picasso. The provided context also mentions Spanish cultural movements like the "Movida Madrileña" and figures like Pedro Almodóvar as examples of contemporary artistic currents exploring freedom and challenging norms, though Almodóvar belongs to a much later generation, it reflects the broader context of modernist and counter-cultural impulses across the Hispanic world during the 20th century.

Recognition and Exhibitions

Throughout his career and posthumously, Ramos Martínez received significant recognition. His early award at the Paris Salon d'Automne was a crucial validation. In 1920, his contributions to art were acknowledged when King Albert I of Belgium reportedly awarded him the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (though this specific combination of honor and bestower might reflect an error in source records, the recognition itself is noted).

In recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in his work, leading to major exhibitions that have solidified his reputation. Key shows include "Alfredo Ramos Martínez & Latin American Modernism" at Louis Stern Fine Arts in Los Angeles (2017), the comprehensive retrospective "Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez" at the Nevada Museum of Art (2018), and the inclusion of his works like La Malinche and Mujeres Indígenas de Oaxaca in significant museum displays and art fairs, such as at the Denver Art Museum (2021) and the Dallas Art Fair (2023). His works are held in major museum collections and continue to be sought after by collectors.

Enduring Legacy: The Father of Mexican Modernism

Alfredo Ramos Martínez's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he forged a unique and influential style that successfully navigated the currents of international modernism while remaining deeply rooted in Mexican identity. He demonstrated how European techniques could be adapted to express distinctly Mexican realities and sensibilities, paving the way for subsequent generations.

As an educator, his founding of the Open-Air Schools represented a radical and democratic shift in art pedagogy, liberating students from academic constraints and encouraging direct engagement with their environment. This initiative played a crucial role in shaping the future direction of Mexican art and nurturing the talents of some of its most important figures. He is rightfully remembered as a foundational pillar of Mexican modern art, an innovator whose contributions continue to resonate.

Conclusion

From his early studies in Monterrey and Mexico City to his formative years in Paris and his final, productive period in California, Alfredo Ramos Martínez charted a remarkable artistic journey. He was a painter of immense skill, a muralist who brought Mexican life to walls both at home and abroad, and a visionary educator who transformed the way art was taught and conceived in his country. His work celebrates the beauty, dignity, and cultural richness of Mexico, leaving behind a vibrant legacy that confirms his status as a true pioneer of modernism in Latin America.