Emmanuel Benner stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. A painter hailing from the historically complex region of Alsace, Benner navigated the demanding Parisian art world, carving out a career distinguished by his sensitive portrayals of the human form, his adeptness with still life, and his engagement with mythological and genre subjects. His work, rooted in the academic traditions of his time yet imbued with a distinct Realist sensibility, offers a window into the artistic currents and cultural preoccupations of an era of profound change.

Early Life and Alsatian Roots

Born on March 28, 1836, in Mulhouse, Alsace, France, Emmanuel Benner, sometimes referred to as Emmanuel Michel Benner, entered a world where art was a familial pursuit. He was the twin brother of Jean Benner, who would also become a painter, and their upbringing in an artistic household undoubtedly nurtured their shared inclination towards the visual arts. Alsace itself, a region with a unique cultural identity, frequently shifting between French and German influence, provided a distinct backdrop to his formative years. This Alsatian heritage would subtly inform the work of many artists from the region, often instilling a particular attention to detail or a specific thematic resonance, particularly in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany in 1871.

The artistic environment of Alsace, while perhaps not the bustling epicenter that Paris represented, had its own traditions. Artists like the earlier master Martin Schongauer had established a strong graphic and painterly legacy in the region. In Benner's own century, figures such as Gustave Doré, another Alsatian, would achieve international fame, though primarily as an illustrator. This regional context, combined with the familial predisposition, set the stage for Emmanuel Benner's artistic journey.

Academic Training and the Parisian Crucible

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Emmanuel Benner understood that Paris was the ultimate destination for serious artistic study and career advancement. He made his way to the capital and enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of academic art education in France. Here, he received rigorous training under several influential masters, each contributing to the development of his technical skills and artistic vision.

Among his principal teachers was Léon Bonnat (1833-1922). Bonnat was a highly respected figure, known for his powerful portraits, his religious paintings, and his admiration for Spanish masters like Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera, whose influence was visible in his own robust realism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro. Bonnat, in turn, had studied with artists such as Federico de Madrazo in Madrid and Léon Cogniet in Paris. He instilled in his students a strong emphasis on anatomical accuracy, solid draughtsmanship, and a direct, unidealized approach to subject matter. This grounding would prove invaluable to Benner.

Benner also studied under Jean-Victor Schnetz, whose own work often depicted Italian peasant life and historical scenes, and possibly under Isidore Pils, known for his military and religious paintings. Other sources mention Eck and Henri-Jean Hennequin as his instructors. This academic training provided Benner with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the traditional hierarchy of genres, from historical and mythological subjects at the apex, down to portraiture, genre scenes, and still life. It was within this structured environment that Benner honed the skills that would later define his career, particularly his nuanced handling of the human figure.

The Salon and the Emergence of a Professional Painter

By his early thirties, around 1866, Emmanuel Benner had committed himself to a full-time career as a painter. The primary avenue for an artist to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish a reputation in 19th-century Paris was the official Salon, organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts (and later by the Société des Artistes Français). The Salon was an annual (or biennial) juried exhibition that drew vast crowds and intense critical scrutiny. To be accepted into the Salon was a mark of professional validation; to win a medal was a significant honor.

Emmanuel Benner made his Salon debut in 1868, exhibiting Game and Fruits (Gibier et Fruits). This work, a still life, demonstrated his early command of texture, color, and composition, traditional strengths of the academic painter. His participation in the Salon would become a regular feature of his career, showcasing his evolving style and thematic interests. The Parisian art scene of this period was vibrant and competitive. Benner was working alongside a multitude of artists, from staunch defenders of academic tradition like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel, to proponents of Realism like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, and the emerging Impressionists who were beginning to challenge the Salon's dominance.

Artistic Style: Realism Tempered with Academic Grace

Emmanuel Benner is generally classified as a Realist painter, yet his Realism was often tempered by the academic discipline of his training. Unlike the more radical Realism of Courbet, which often carried a strong socio-political charge and a deliberate rejection of idealized beauty, Benner's work, while truthful and direct, often retained a degree of elegance and a focus on aesthetic harmony.

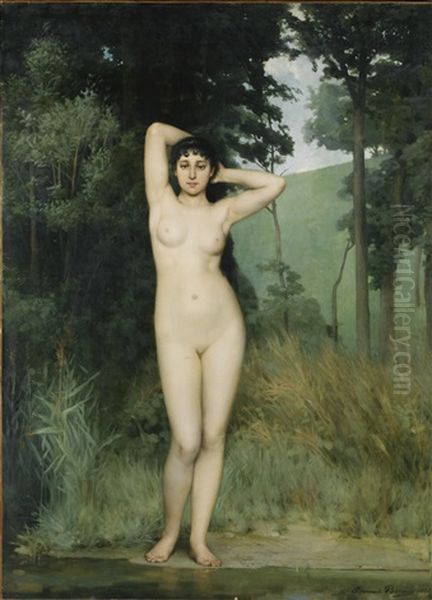

His style was characterized by what contemporaries described as "natural colors and vivid expression." He excelled in figure painting, particularly the female nude, a genre that was highly popular at the Salon but also subject to varying interpretations and standards of decorum. Academic nudes, often presented within mythological or allegorical contexts, such as Cabanel's The Birth of Venus (1863) or Bouguereau's numerous depictions of nymphs and goddesses, were generally acceptable. Benner's nudes, while sometimes framed by mythology, often aimed for a more direct, less idealized representation, focusing on the natural beauty and vulnerability of the human form.

His genre scenes and portraits also reflected this commitment to verisimilitude. He sought to capture the character and emotional state of his subjects, often with simple yet evocative compositions. The themes he explored were diverse, ranging from intimate domestic scenes and studies of everyday life to more ambitious mythological and allegorical compositions.

Significant Works and Thematic Exploration

Throughout his career, Emmanuel Benner produced a considerable body of work, with several paintings standing out as representative of his style and thematic preoccupations.

His early Salon entry, Game and Fruits (1868), established his credentials as a skilled still-life painter. This genre, while lower in the academic hierarchy, allowed artists to demonstrate their mastery of technique, their ability to render different textures – fur, feathers, fruit skin, metal, ceramic – and their understanding of light and shadow.

Works like Guitar Player (1873) and Revérie (1875) suggest an interest in genre scenes that capture moments of quiet contemplation or everyday activity. These paintings likely focused on individual figures, allowing Benner to explore character and mood through pose, expression, and the careful depiction of costume and setting.

One of his most noted works is Madeleine in the Desert (or Sainte Madeleine au désert, also referred to as Madame de la Désert), a religious painting that found a home in the Musée d'Art Moderne et Contemporain in Strasbourg. This subject, Mary Magdalene as a penitent hermit, was a popular one in Christian art, allowing for the depiction of intense emotion and, often, the female nude in a context of spiritual devotion. Benner's interpretation would have balanced the religious narrative with his characteristic attention to the human form.

His painting Hunters in Wait showcases another facet of his oeuvre, likely a genre scene depicting figures in a landscape, demonstrating his ability to integrate figures into a natural setting and capture a sense of narrative tension or anticipation. Other works mentioned include A Study and The Sleeper, titles that suggest intimate figure studies, possibly focusing on the nude or semi-nude form in repose, allowing for an exploration of vulnerability and tranquility. Nu Près Du Rive (Nude Near the Riverbank) clearly falls into his favored category of nudes in a natural setting, a common motif that allowed for a harmonious blend of figure and landscape.

Benner also ventured into mythological subjects, a staple of academic art. Venus Appearing to the Three Graces would have provided an opportunity for a complex multi-figure composition, celebrating classical ideals of beauty. Similarly, his painting Daphne drew from Greek mythology, depicting the nymph pursued by Apollo who is transformed into a laurel tree. Such subjects allowed artists to showcase their knowledge of classical literature and their skill in rendering dynamic, idealized figures.

Other notable titles include The Invader (L'Intrus) and Two Mothers (Les Deux Mères). The former might suggest a narrative scene with dramatic potential, while the latter could be an intimate genre scene exploring themes of maternity and domesticity. These works, exhibited at the Salon, contributed to his reputation and demonstrated the breadth of his thematic interests.

The Alsatian Context Revisited: Art and Identity

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 and the subsequent German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine had a profound impact on the people of the region, including its artists. This historical trauma often found expression in art, sometimes overtly patriotic, sometimes elegiac, reflecting a sense of loss and a desire to preserve cultural identity. While it's not always explicit in Benner's known works, his Alsatian origins would have made him keenly aware of these currents.

Artists like Jean-Jacques Henner (1829-1905), another prominent Alsatian painter and a contemporary with whom Benner likely had connections, often imbued his work with a melancholic, nostalgic quality. Henner was particularly known for his ethereal nudes and his distinctive use of sfumato. The shared regional background might have fostered a sense of community or shared sensibility among Alsatian artists working in Paris. The choice of subjects, even if seemingly universal like mythology or genre, could sometimes carry subtle regional inflections or resonate differently with an audience aware of the artist's origins.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and the Artistic Milieu

Emmanuel Benner's career unfolded within a dynamic and competitive artistic environment. His twin brother, Jean Benner (1836-1906), was his closest artistic contemporary. Jean also pursued a career as a painter, often focusing on portraits, genre scenes, and particularly, depictions of Capri, an island that fascinated many artists of the period. The brothers, while developing their individual styles, shared a common artistic heritage and likely provided mutual support and critique.

Beyond his brother, Benner's teachers, particularly Léon Bonnat, remained influential figures in the Parisian art world. Bonnat's studio attracted many students who would go on to achieve recognition, including artists like Gustave Caillebotte (though Caillebotte would become more associated with Impressionism), Thomas Eakins (the American Realist), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. While Benner was not a direct peer of these later students in terms of artistic direction, they were all part of the broader ecosystem of academic training.

Benner exhibited alongside numerous other artists at the Salon. Records indicate he showed works at the Société des Artistes Français in the 1880s, where he would have been in the company of painters like Léon Maxime Faivre, known for his historical and genre scenes, and Fernand Cormon, a celebrated painter of historical and prehistoric subjects, whose studio also trained prominent artists like Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec. The Salon was a place where diverse talents converged, from established masters like Jean-Léon Gérôme, with his meticulously detailed Orientalist and historical paintings, to younger artists vying for attention.

While direct "collaborations" in the modern sense were less common for easel painters, the shared experience of academic training, studio life, and Salon exhibitions fostered a complex web of influences, rivalries, and associations. Artists learned from each other, responded to prevailing trends, and sought to distinguish themselves within a crowded field. Benner's relationship with these contemporaries was likely one of professional respect and the typical competitive spirit of the Salon system.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

Emmanuel Benner continued to exhibit regularly at the Paris Salon throughout his career, a testament to his consistent output and the acceptance of his work by the Salon juries. In 1881, he received a significant mark of official recognition: a third-class medal at the Salon. Such awards were crucial for an artist's career, enhancing their reputation, attracting commissions, and potentially leading to state purchases of their work.

His paintings found their way into private collections and some public institutions, such as the aforementioned Madeleine in the Desert in Strasbourg. His dedication to his craft and his ability to consistently produce work that met the standards of the Salon ensured his place as a respected, if not revolutionary, figure in the French art world of his time.

Emmanuel Benner passed away on September 24, 1896, in Nantes, France. He left behind a body of work that reflects the artistic values and preoccupations of his era. While he may not have achieved the posthumous fame of some of his more avant-garde contemporaries, his contributions to French Realism and academic painting are undeniable.

Historically, Benner is seen as a skilled practitioner of academic Realism. His strengths lay in his sensitive rendering of the human form, his competent handling of diverse subject matter, and his ability to create works that were both aesthetically pleasing and emotionally resonant within the conventions of his time. Some critiques, common for many Salon painters, might suggest that his work, while technically proficient, occasionally lacked the profound social commentary of a Daumier or the groundbreaking vision of the Impressionists. However, this is to judge him by standards that were not necessarily his primary aim. His focus was often on the intrinsic beauty of his subjects, whether a human figure, a still life arrangement, or a mythological narrative, rendered with honesty and skill.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Emmanuel Benner's artistic journey from Mulhouse to the heart of the Parisian art world is a story of dedication, skill, and consistent engagement with the prevailing artistic currents of the 19th century. As a product of the French academic system, he mastered its techniques and applied them to a range of subjects, from the intimate to the grand. His particular affinity for the human figure, especially the nude, allowed him to explore themes of beauty, vulnerability, and emotion with a Realist's eye for truth and an academician's sense of form.

While the towering figures of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism often dominate narratives of late 19th-century art, artists like Emmanuel Benner played a vital role in the artistic life of their time. They populated the Salons, satisfied the tastes of collectors, and maintained a high standard of craftsmanship. His works, characterized by their naturalism, expressive power, and technical finesse, offer valuable insights into the mainstream of French painting during a period of significant artistic evolution. Emmanuel Benner remains a testament to the enduring appeal of well-crafted, thoughtfully conceived art that seeks to capture the complexities of the human experience and the beauty of the visible world. His legacy is that of a talented and respected Alsatian painter who successfully navigated the demanding art world of Paris, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be appreciated for its skill and sensitivity.