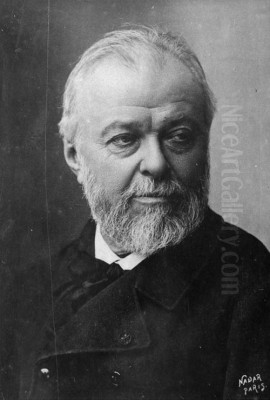

Jean-Jacques Henner (March 5, 1829 – July 23, 1905) stands as a distinctive and highly regarded figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Hailing from the Alsace region, Henner carved a unique path, blending academic precision with a deeply personal, atmospheric style. He became renowned for his masterful use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) and sfumato (soft, hazy transitions), techniques he employed to create evocative nudes, poignant religious scenes, and sensitive portraits. Though working during the rise of Impressionism, Henner maintained his own artistic voice, drawing inspiration from Renaissance masters while infusing his work with a melancholic, often dreamlike quality that resonated with Symbolist undercurrents. His legacy endures through his captivating paintings and the dedicated museum preserving his work in Paris.

Alsatian Roots and Early Artistic Formation

Jean-Jacques Henner was born in the small village of Bernwiller, located in the Haut-Rhin department of Alsace, France. This region, with its distinct cultural identity poised between France and Germany, would remain a touchstone for the artist throughout his life. His family background was modest; his parents were peasant farmers. However, his innate talent for drawing became apparent at an early age.

His formal artistic journey began locally. In the nearby town of Altkirch, his abilities were first seriously recognized by his drawing teacher, Charles Goutzwiller. Goutzwiller encouraged the young Henner, providing him with foundational instruction and likely playing a crucial role in nurturing his nascent artistic ambitions. This early encouragement set the stage for more advanced training.

Henner subsequently moved to Strasbourg, the regional capital, to continue his studies under the guidance of Gabriel Guérin. At Guérin's studio, Henner received a more structured, traditional art education. During this period, he honed his skills, particularly in portraiture, often using family members and local Alsatian notables as subjects. He also depicted scenes reflecting the rural life of his native region, demonstrating an early connection to the people and landscapes of Alsace that would surface repeatedly in his later work. This formative period under Goutzwiller and Guérin provided Henner with essential technical skills and solidified his artistic calling.

Paris and the École des Beaux-Arts

Around 1847, seeking to further his artistic education at the highest level, Henner made the pivotal move to Paris. The French capital was the undisputed center of the art world, offering unparalleled opportunities for training and exposure. Henner successfully gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of academic art instruction in France.

At the École, he entered the ateliers of two respected academic painters: Michel Martin Drolling and François-Édouard Picot. Both Drolling and Picot were established figures within the academic system, known for their history paintings and portraits executed with technical proficiency and adherence to classical ideals. Under their tutelage, Henner immersed himself in the rigorous academic curriculum, which emphasized drawing from classical sculpture and the live model, studying anatomy, and mastering the principles of composition and perspective inherited from the Old Masters. Drolling is noted to have particularly encouraged Henner's interest in portraiture, while Picot guided him towards the idealized forms favored by the Academy.

This period was crucial for Henner's technical development. He absorbed the meticulous draftsmanship and structured approach characteristic of French academic painting. He competed alongside other ambitious young artists, navigating the highly competitive environment of the École, where success was often measured by performance in concours (competitions) and the ultimate goal for many was the coveted Prix de Rome. His training under Drolling and Picot equipped him with the skills necessary to succeed within the established art system of the time.

Triumph in Rome: The Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A defining moment in Henner's early career arrived in 1858 when he won the prestigious Prix de Rome for painting. This highly sought-after prize, awarded annually by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the pinnacle of academic achievement for young French artists. Henner secured the award with his painting Adam and Eve Finding the Body of Abel. This work, depicting the biblical tragedy with dramatic intensity and a sophisticated handling of anatomy and emotion, was considered notably innovative for its time within the competition's context. Its powerful use of light and shadow already hinted at the direction his mature style would take.

Winning the Prix de Rome was a significant turning point. It provided Henner with a generous stipend and the opportunity to study for several years (typically four to five) at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the magnificent Villa Medici. This period, from roughly 1859 to 1865, was profoundly influential. Immersed in the artistic treasures of Italy, Henner dedicated himself to studying the works of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque masters firsthand.

He was particularly drawn to the Venetian school, admiring the rich color and atmospheric qualities found in the works of artists like Titian and Giorgione. However, the most profound impact came from masters of light and shadow. He deeply studied the dramatic intensity and realism of Caravaggio's chiaroscuro and the soft, graceful sfumato employed by Correggio. These influences were instrumental in shaping Henner's own signature style, characterized by figures emerging from dark, mysterious backgrounds and bathed in a soft, often ethereal light. His time in Italy was not solely dedicated to studying the past; he also interacted with fellow artists. During his Roman sojourn, he formed acquaintances with contemporaries such as the future Impressionist Edgar Degas and the Symbolist pioneer Gustave Moreau, sharing experiences even as their artistic paths diverged.

The Henner Style: Light, Shadow, and Idealized Form

Upon his return to Paris from Italy, Jean-Jacques Henner's artistic voice had fully matured, establishing the distinctive style for which he would become famous. His Italian studies, particularly of Correggio and Caravaggio, had solidified his fascination with the interplay of light and shadow. He became a master of chiaroscuro, using deep, often impenetrable dark backgrounds from which his subjects would softly emerge, illuminated by a focused, gentle light source.

Complementing his use of chiaroscuro was his adept handling of sfumato. Inspired by Leonardo da Vinci and Correggio, Henner employed soft, hazy transitions between tones and colours, blurring contours and creating an atmospheric veil that lent his figures a dreamlike or melancholic quality. This technique was particularly effective in rendering flesh tones, giving his nudes a characteristic soft, almost luminous appearance. His palette was often restrained, dominated by warm earth tones, deep reds, and luminous whites, enhancing the intimacy and mystery of his scenes.

While grounded in the academic tradition of careful drawing and anatomical accuracy learned at the École des Beaux-Arts, Henner's style departed from the crisp linearity and bright, even lighting often favored by contemporaries like Jean-Léon Gérôme or William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Henner's figures, though idealized, possessed a subtle realism and psychological depth. His approach was less about narrative clarity or mythological grandeur and more focused on evoking mood, intimacy, and a sense of quiet contemplation. This unique blend of academic foundation, Renaissance influence, and personal sensibility set him apart in the Parisian art scene.

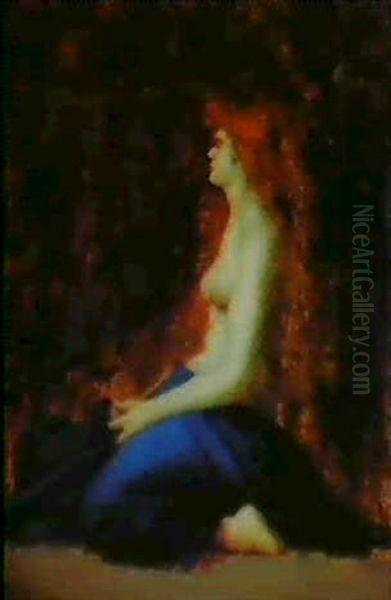

Signature Subjects: Nudes, Religion, and Portraits

Henner's oeuvre consistently revolved around a few key themes, which he explored with remarkable dedication throughout his career. Perhaps most famously, he specialized in painting the female nude. His nudes, often depicted as solitary figures like nymphs, naiads, or bathers, are rarely set in specific mythological contexts. Instead, they inhabit dimly lit, indeterminate landscapes or interiors, enhancing their enigmatic quality. Works like Bather Asleep (1863) or The Naiad (c. 1881) exemplify this genre. A recurring motif was the depiction of women with striking red hair, their pale skin glowing against the dark backgrounds – a feature that became almost a trademark of his idealized female figures.

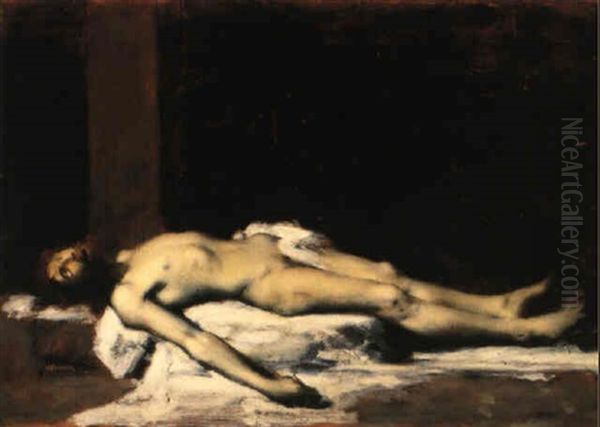

Religious subjects also formed a significant part of his output, continuing from his Prix de Rome success. He revisited biblical themes, often focusing on moments of pathos and introspection. His various depictions of Saint Sebastian, Mary Magdalene, and works like Christ Entombed (1879) are characterized by their dramatic lighting and deep spirituality. Unlike grander, more didactic religious paintings common in the academic tradition, Henner's interpretations often feel more personal and contemplative, emphasizing the human emotion within the sacred narrative.

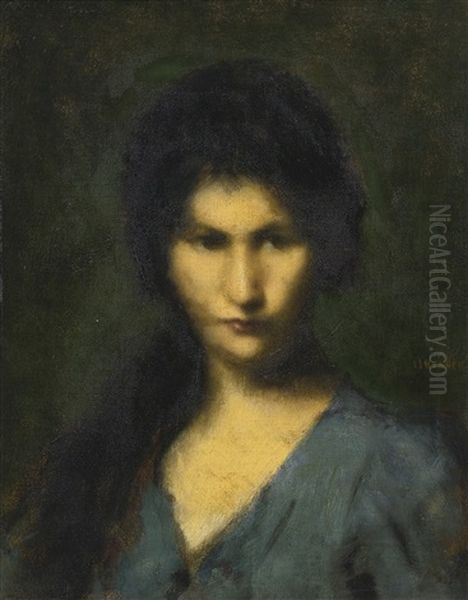

Portraiture was another mainstay of Henner's career, and he was highly sought after as a portraitist. He painted prominent figures of Parisian society as well as individuals from his native Alsace. His portraits, while capturing a strong likeness, are imbued with the same stylistic characteristics as his other works: soft focus, subtle modeling, and an introspective mood. He avoided harsh details, preferring to suggest the sitter's personality through pose, expression, and the atmospheric play of light and shadow. Notable examples include portraits of fellow artists, writers, and members of the Alsatian community in Paris.

Salon Success and Official Recognition

![Jeune Fille Etendue [, A

Reclining Nude, Oil On Cardboard, Signed, Dedicated And Dated 1891 On

The Reverse ] by Jean-Jacques Henner](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/2314793/m/jeanjacques-henner-jeune-fille-etendue-a-reclining-nude-oil-on-cardboard-signed-dedicated-and-dated-1891-on-the-reverse--271559fe.jpg)

Jean-Jacques Henner achieved considerable success and recognition within the official art establishment of his time. He became a regular and highly anticipated exhibitor at the annual Paris Salon, the most important venue for artists seeking public exposure and critical validation. His distinctive style, while perhaps less controversial than the emerging Impressionists, consistently attracted attention and praise. Works like Chaste Susanna (1865), purchased by the state for the Musée du Luxembourg (its collections now largely housed in the Musée d'Orsay), cemented his reputation early on.

His paintings were popular with collectors, and the French state frequently acquired his works for national and regional museums. This official patronage underscored his standing within the art world. His achievements were further recognized through prestigious honors. In 1889, he was elected to the esteemed Académie des Beaux-Arts, taking the seat previously held by the prominent academic painter Alexandre Cabanel. This election signified his acceptance into the highest echelons of the French artistic hierarchy.

Further accolades followed. He received the Legion of Honour, initially as a Knight in 1873, eventually rising to the rank of Grand Officer. At the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1900, a major international showcase, Henner was awarded a Grand Prix for his contributions, confirming his status as a leading figure in contemporary French art. Anecdotes suggest he also achieved significant financial success, reportedly earning a substantial income, though he was known for his frugal lifestyle, choosing to save rather than spend lavishly. This combination of critical acclaim, state patronage, official honors, and market success marked Henner as a major figure in the artistic landscape of the French Third Republic.

Henner and His Contemporaries

Positioning Jean-Jacques Henner within the complex art world of the latter half of the 19th century reveals his unique stance. He operated largely within the academic system, achieving success through the Salon and official institutions, yet his style possessed a personal quality that set him apart from stricter academicians like William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose works often featured sharper details, brighter palettes, and more explicit narratives.

Henner's career unfolded concurrently with the rise of Impressionism. While he knew artists like Edgar Degas and was certainly aware of the revolutionary changes being pioneered by Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro, Henner did not embrace their techniques or aesthetic goals. He remained committed to studio work, careful modeling, and traditional subject matter, contrasting sharply with the Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting moments, plein-air painting, and the optical effects of light and colour. Despite these differences, Henner maintained a level of respect; he was not typically a target of the harsh criticism directed at some other academic figures.

His work finds closer affinities with certain aspects of Symbolism. Although not a Symbolist painter in the programmatic sense like his acquaintance Gustave Moreau or Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Henner's emphasis on mood, mystery, introspection, and the evocative power of shadow aligns with Symbolist sensibilities. His dreamlike nudes and melancholic landscapes resonated with a desire to explore subjective experience and inner worlds, themes central to the Symbolist movement. He thus occupies an interesting position, bridging the academic tradition he mastered with a more modern, introspective, and atmospheric approach that anticipated or paralleled aspects of Symbolism.

A Dedicated Teacher

Beyond his own prolific output, Jean-Jacques Henner also made a significant contribution as an educator. He maintained a successful private atelier in Paris, attracting numerous students eager to learn from a recognized master. His reputation for technical skill, particularly in rendering the human form and manipulating light, made his studio a popular choice for aspiring artists.

Notably, Henner's studio was known for being welcoming to female artists during a period when opportunities for women in the arts were still relatively limited. While the École des Beaux-Arts did not officially admit women until 1897, private ateliers like Henner's provided crucial training grounds. He is known to have taught a number of women, contributing to their professional development. Among his students was the painter Germaine Desgranges. While sometimes informally linked to artists like Suzanne Valadon (who greatly admired him), documented evidence confirms his role in training numerous, albeit less famous today, female painters.

His teaching methods likely reflected his own artistic principles, emphasizing strong drawing skills, the study of the Old Masters, and careful attention to tone and atmosphere. Through his role as a teacher, Henner directly influenced the next generation of artists, transmitting aspects of his technique and aesthetic vision. This pedagogical activity further cemented his importance within the Parisian art community of the late 19th century.

Spotlight on Masterpieces

Several key works stand out in Jean-Jacques Henner's extensive oeuvre, encapsulating his style and thematic concerns:

Adam and Eve Finding the Body of Abel (1858): This was the painting that won Henner the Prix de Rome. Housed today at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, it demonstrates his early mastery of academic conventions – strong anatomical rendering, classical composition, and a dramatic historical/biblical subject. However, the intense emotion and the powerful use of chiaroscuro, with the figures dramatically lit against a dark, foreboding landscape, already signal the direction his art would take. It was a work that fulfilled academic expectations while hinting at a more personal, expressive power.

Chaste Susanna (1865): Exhibited at the Salon of 1865 and now a highlight of the Musée d'Orsay, this painting depicts the biblical story of Susanna spied upon by the elders. Henner’s interpretation focuses tightly on Susanna, her nude form rendered with characteristic softness and luminosity against a dark, ambiguous background. The elders are barely visible in the shadows. The work combines classical subject matter with a subtle eroticism and vulnerability, showcasing Henner's skill in rendering flesh tones and creating an atmosphere of quiet tension and intimacy through his signature sfumato and chiaroscuro.

The Naiad (c. 1881): Representative of Henner's popular theme of solitary female figures in nature, this work (versions exist in various collections) typically features a red-haired nymph or water spirit reclining by a pool in a dimly lit, verdant setting. The figure's body seems to absorb and reflect the soft light, her contours melting into the shadowy landscape through the use of sfumato. The mood is melancholic, dreamlike, and mysterious, embodying the idealized yet intimate vision of femininity that became synonymous with Henner's name.

Saint Sebastian (various versions, e.g., Study, 1888, Musée d'Orsay): Henner returned to the theme of Saint Sebastian multiple times. These depictions often focus on the saint's suffering and martyrdom, emphasizing pathos through the idealized rendering of the male form and the dramatic play of light across the body. Compared to earlier Renaissance depictions (like those by Andrea Mantegna or Perugino), Henner's versions are often more intimate and emotionally charged, using his characteristic dark palette and soft modeling to highlight the spiritual and physical ordeal of the saint.

These works, among many others, illustrate the core elements of Henner's art: technical mastery inherited from academic training, profound influence from Italian masters of light and shadow, a focus on idealized human form (particularly the female nude), and the creation of a unique atmospheric mood blending realism, melancholy, and mystery.

The Alsatian Heart

Despite spending most of his adult life and achieving fame in Paris, Jean-Jacques Henner maintained a deep and enduring connection to his native Alsace. This bond manifested itself both personally and artistically. He returned frequently to the region, particularly to his hometown of Bernwiller, finding respite and inspiration away from the bustle of the capital.

His Alsatian roots are reflected in his artwork in several ways. He painted numerous landscapes inspired by the region, though often these were not direct transcriptions but rather idealized or remembered views, imbued with his characteristic soft light and melancholic atmosphere. He also continued to paint portraits of Alsatian people, both those he knew from his youth and members of the Alsatian community who, like him, had moved to Paris.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, which resulted in the annexation of Alsace and part of Lorraine by Germany, deeply affected Henner, as it did many Alsatians. Following the war, his depictions of Alsatian subjects, particularly his idealized images of Alsatian women often dressed in traditional costume (like L'Alsace. Elle attend - Alsace. She waits), took on a patriotic significance for French audiences, symbolizing the lost province and the hope for its return. His work became, in part, a visual embodiment of Alsatian identity and resilience during a difficult period in French history. This strong regional connection adds another layer to the understanding of Henner's life and art.

Legacy: The Musée Henner and Art Historical Standing

Jean-Jacques Henner died in Paris on July 23, 1905, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant reputation. His legacy is most tangibly preserved today through the Musée National Jean-Jacques Henner, located in a 19th-century mansion near Parc Monceau in Paris. Established following a bequest by the artist's niece after his death, the museum opened to the public in 1924. It houses the largest collection of Henner's works, including paintings, drawings, sketches, and personal memorabilia, offering an unparalleled insight into his artistic process and career. The museum itself, with its preserved studio atmosphere, helps to keep his memory alive.

In terms of art historical standing, Henner's reputation experienced fluctuations typical for many successful 19th-century artists whose work fell outside the dominant narrative of modernist progression. While immensely popular during his lifetime, his fame somewhat diminished during the mid-20th century as tastes shifted towards abstraction and the avant-garde. However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for his art.

He is now recognized for his exceptional technical skill, particularly his mastery of chiaroscuro and sfumato, which created a unique and instantly recognizable style. He is seen as an artist who successfully navigated the academic system while developing a highly personal and evocative vision. His ability to blend realism with idealism, and his creation of atmospheric, psychologically resonant images, places him as an important figure bridging traditional academic painting and the more subjective concerns of Symbolism. His influence can be traced in the work of some later figurative painters and portraitists who admired his handling of light and mood. Artists mentioned for context include contemporaries like the Realist Gustave Courbet and fellow academics like Gérôme and Bouguereau, highlighting Henner's distinct path amidst the diverse artistic currents of his time.

Conclusion

Jean-Jacques Henner remains a compelling figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. An artist deeply rooted in his Alsatian origins, he absorbed the rigorous training of the Parisian academic system and synthesized it with profound inspiration drawn from the Italian masters of the Renaissance and Baroque, particularly Caravaggio and Correggio. The result was a unique and enduring style characterized by a masterful command of light and shadow – the dramatic intensity of chiaroscuro softened by the delicate, atmospheric haze of sfumato.

His recurring themes – the idealized female nude emerging from darkness, poignant religious figures caught in moments of spiritual intimacy, and sensitive portraits imbued with melancholic grace – all bear his unmistakable signature. While contemporary with the Impressionists, he forged his own path, achieving widespread recognition and official honors without compromising his distinct artistic vision. His work, often hovering between realism and dreamlike suggestion, resonated with the introspective mood of Symbolism. Today, Jean-Jacques Henner is celebrated not only for his technical brilliance but also for his ability to evoke profound emotion and mystery through the subtle interplay of form, shadow, and light, securing his place as a unique master of atmosphere in French painting.