Enrique Atalaya stands as an intriguing figure in the art history of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A Spanish artist who found his primary stage in the bustling art world of Paris, Atalaya developed a distinct style that blended elements of Realism with the burgeoning techniques of Impressionism. His work primarily focused on capturing the atmosphere and specific locales of Paris, particularly its older, rapidly changing districts, leaving behind a valuable visual record of the city during a transformative era.

From Spain to the City of Light

Born in Murcia, Spain, in 1851, Enrique Atalaya's early life and artistic training in his home country remain relatively undocumented in readily available sources. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation, he was drawn to Paris, which by the latter half of the nineteenth century had firmly established itself as the undisputed capital of the Western art world. The city offered unparalleled opportunities for artistic study, exhibition, and engagement with the avant-garde.

Atalaya made the pivotal move to Paris around 1880. This placed him directly into the vibrant, dynamic, and often contentious artistic environment of the French Third Republic. It was a time when Impressionism, having weathered initial critical storms, was gaining wider acceptance, while new movements like Post-Impressionism and Symbolism were beginning to emerge. Atalaya embraced his new home, becoming a French citizen in 1881, signaling his intention to build his career and life in France.

Artistic Style: Realism Meets Impressionism

Enrique Atalaya's artistic approach is often characterized as a synthesis of Realism and Impressionism. Unlike the core Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who prioritized capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with rapid, broken brushwork, Atalaya often retained a stronger commitment to detailed observation and solid form, characteristic of Realist traditions. However, he clearly absorbed and utilized Impressionist techniques to enhance his depictions.

His paintings, particularly his cityscapes, demonstrate a keen sensitivity to light and shadow, using a palette that could be both nuanced and luminous. He employed visible, sometimes delicate, brushstrokes to convey texture and atmosphere, moving away from the smooth, polished finish favored by academic painters. His focus was often on the tangible reality of Parisian streets, buildings, and the daily life unfolding within them, rendered with an eye for accuracy but softened by an Impressionistic sensibility.

This blend allowed Atalaya to create works that were both representational and evocative. He captured the specific character of Parisian locations while also imbuing them with a sense of mood and time. His preference for depicting "Old Paris" suggests an interest not just in topography, but also in the historical layers and perhaps a touch of nostalgia for the parts of the city less affected by Baron Haussmann's grand modernization projects. He worked in both oil and watercolor, showing proficiency in each medium.

Life and Connections in Paris

Settling in Paris around 1880 meant Atalaya arrived during a period of intense artistic ferment. The Impressionist group had held several independent exhibitions, challenging the dominance of the official Salon. Artists debated new theories of color and form in the cafés of Montmartre and Batignolles. Atalaya navigated this world and established connections within the city's cultural circles.

Among his notable acquaintances was Angelo Mariani, a pharmacist famous for inventing "Vin Mariani," a popular coca-infused wine endorsed by numerous celebrities of the era. Mariani was also a significant patron of the arts. This connection proved fruitful for Atalaya, leading to a major commission. He was also reportedly friends with the influential Naturalist writer Émile Zola, whose novels often provided gritty, realistic portrayals of modern Parisian life, suggesting a potential shared interest in observing and documenting the contemporary world.

These connections indicate Atalaya's integration into the Parisian cultural milieu, moving beyond the circles of purely Spanish expatriate artists and engaging with French patrons and intellectuals. His life in Paris coincided with the Belle Époque, a period of relative peace, prosperity, and cultural dynamism in France, and his work reflects the visual character of this era.

Major Works: Chronicling Old Paris

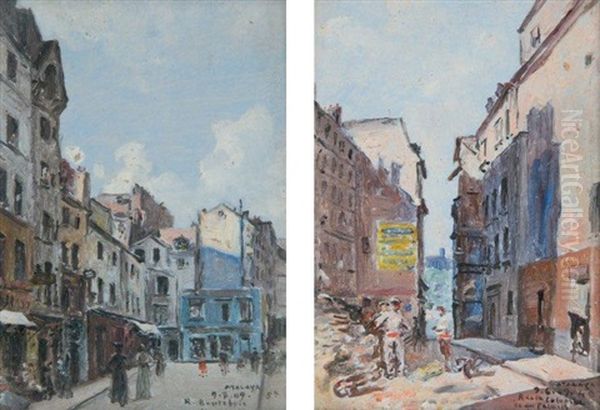

Perhaps Enrique Atalaya's most significant and recognized achievement is the series of watercolors titled "Vues du vieux Paris" (Views of Old Paris). Commissioned by his friend and patron Angelo Mariani, this extensive series comprises 52 individual works, meticulously created between 1909 and 1910. Each watercolor is carefully dated and signed, underscoring the artist's methodical approach.

This series stands out for its specific focus on the older quarters of Paris, capturing streets, squares, and buildings that retained their pre-Haussmann character or possessed historical significance. The works are noted for their remarkable detail and accuracy, described by some as possessing an almost photographic realism, unusual for works associated with Impressionism. This suggests a documentary impulse behind the project, perhaps encouraged by Mariani, to preserve a visual record of a Paris that was continually evolving and, in parts, disappearing.

The dedication of the series to Mariani highlights the importance of patronage in Atalaya's career. These watercolors showcase his technical skill in the medium, his ability to handle complex architectural subjects, and his consistent artistic vision across a large body of related works. They remain a valuable resource for understanding the topography and atmosphere of Paris in the years leading up to World War I.

Beyond this major series, other works by Atalaya have appeared in auction records, indicating his continued production. Titles such as "Environnements de Paris avec l' Tour Eiffel" (Paris Surroundings with the Eiffel Tower) show his engagement with iconic modern landmarks as well, while oil paintings like "Scènes champêtres" (Pastoral Scenes) suggest he occasionally explored different genres beyond the urban landscape.

The 1900 Exposition Universelle

A significant milestone in Atalaya's career was his participation in the Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1900. This massive world's fair was a showcase of international technological, industrial, and cultural achievements, and the art exhibitions were a central feature, attracting huge audiences. Atalaya exhibited works described as being in the Impressionist style.

His participation and reported success at the Exposition indicate a level of recognition and acceptance within the Parisian art establishment at the turn of the century. By 1900, Impressionism, while still debated, had become a more familiar and appreciated style compared to its radical beginnings in the 1870s. Atalaya's blend of Impressionist technique with recognizable subject matter likely appealed to the tastes of the time. Success at such a high-profile international event would have enhanced his reputation considerably.

Contemporaries in the Parisian Art World

Enrique Atalaya worked in Paris during a period populated by a dazzling array of artistic talent, representing a wide spectrum of styles and movements. While the giants of Impressionism like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir continued to be influential, exploring light and color in landscapes and scenes of leisure, the artistic landscape was diverse.

Atalaya shared the city with Edgar Degas, whose sharp observations captured dancers, racetracks, and intimate moments of modern life, often with innovative compositions. The dedicated landscape Impressionists Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley continued to paint the environs of Paris with sensitivity. American expatriates made significant contributions, notably Mary Cassatt, known for her tender depictions of mothers and children, and the virtuosic portraitist John Singer Sargent, who frequently worked in Paris.

New approaches were emerging. The pointillist techniques of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac offered a more scientific system for applying color, creating luminous and structured compositions. Post-Impressionist pioneers like Paul Gauguin and, for a time, Vincent van Gogh, explored more expressive uses of color and form, often seeking subjects beyond Paris. The vibrant, sometimes gritty, nightlife of Montmartre found its definitive chronicler in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Simultaneously, the Symbolist movement offered an alternative to Impressionism's focus on the external world, with artists like Odilon Redon, Gustave Moreau, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes delving into dreams, myths, and subjective states. Academic painting still held sway at the official Salon, though its dominance was waning. Furthermore, Atalaya was not the only talented Spanish artist drawn to Paris; his compatriot Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, famous for his sun-drenched Valencian beach scenes, also achieved great success in the French capital around the turn of the century. Atalaya navigated this rich and complex artistic milieu, finding his own path amidst these diverse talents.

Later Years and Legacy

Enrique Atalaya continued to work into the early twentieth century, completing his significant watercolor series of Old Paris in 1910. He passed away in 1914, the year that marked the beginning of World War I, an event that would profoundly reshape European society and culture, including the art world. His death occurred just as Fauvism, Cubism, and other early Modernist movements were radically challenging previous artistic conventions.

Compared to the towering figures of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Enrique Atalaya remains a relatively lesser-known artist today. His work did not break new ground in the same way as Monet, Degas, or Cézanne. However, his contribution should not be overlooked. He was a skilled and dedicated painter who successfully synthesized elements of Realism and Impressionism to create a personal style suited to his chosen subject matter.

His most enduring legacy lies in his depictions of Paris, particularly the "Vues du vieux Paris" series. These works offer more than just aesthetic pleasure; they serve as valuable historical documents, capturing the specific appearance and atmosphere of the city during the Belle Époque. They provide a visual counterpoint to the grand boulevards often depicted by others, focusing instead on the enduring charm and character of older neighborhoods. He represents a cohort of talented artists who, while perhaps not revolutionaries, formed the rich fabric of the Parisian art scene and contributed significantly to the visual culture of their time.

Conclusion

Enrique Atalaya exemplifies the international character of the Parisian art world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A Spaniard by birth, he fully integrated into the artistic life of his adopted city, becoming a French citizen and forging connections with local patrons and intellectuals. His art skillfully blended the observational detail of Realism with the atmospheric light and color of Impressionism, resulting in compelling depictions of Paris.

His major series of watercolors, "Vues du vieux Paris," stands as his most significant achievement, a meticulous and loving portrayal of the city's historic quarters commissioned by Angelo Mariani. His success at the 1900 Exposition Universelle confirmed his contemporary recognition. While perhaps overshadowed in art history by more famous contemporaries like Monet, Renoir, Degas, or Toulouse-Lautrec, Atalaya was a talented and productive artist whose work offers a unique window onto Belle Époque Paris, securing his place as a noteworthy chronicler of the City of Light.