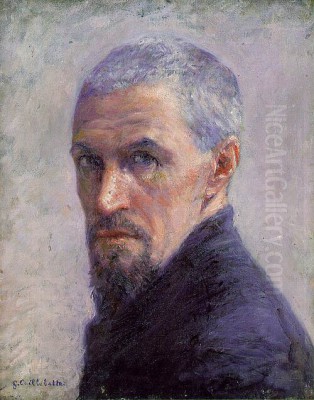

Gustave Caillebotte stands as a unique and pivotal figure in the narrative of late 19th-century French art. Born into privilege yet deeply engaged with the artistic currents of his time, he navigated the worlds of painting, patronage, and collecting with remarkable dedication. While often associated with the Impressionist movement, his artistic style retained a distinctive character, blending meticulous realism with innovative perspectives that captured the essence of modern Parisian life. His financial independence allowed him not only to pursue his own artistic vision but also to become an indispensable supporter of his fellow artists, ensuring the survival and eventual triumph of the Impressionist group.

Early Life and Formative Years

Gustave Caillebotte was born on August 19, 1848, in Paris, into a family of considerable wealth and social standing. His father, Martial Caillebotte, was a successful businessman who had inherited a family textile enterprise involved in military supplies, and he also served as a judge at the Seine Department's Tribunal de Commerce. His mother, Céleste Daufresne, also came from an affluent background. This privileged upbringing provided Gustave with financial security and access to education and culture from a young age.

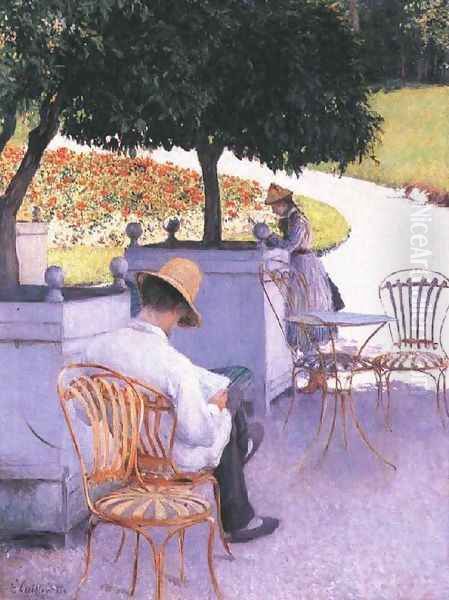

The family initially lived in the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis before moving to a more prestigious residence in the rue de Miromesnil. They also owned a substantial country estate in Yerres, a town southeast of Paris on the Yerres River. It was during the family's summer stays at this idyllic estate that Gustave first began to explore his interest in drawing and painting, capturing the leisurely activities and landscapes around him.

Despite his burgeoning artistic inclinations, Caillebotte followed a conventional path for a young man of his class. He pursued legal studies, earning a law degree in 1868 and obtaining his license to practice law in 1870. His legal career, however, was short-lived. He was drafted into the Franco-Prussian War shortly after qualifying, serving in the Garde Nationale Mobile de la Seine. This experience, coupled with the changing social landscape of Paris, likely influenced his later artistic focus on contemporary life.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1874 with the death of his father. Gustave, along with his younger brothers René (who died shortly after in 1876) and Martial, inherited a substantial fortune. This inheritance granted Caillebotte complete financial independence, freeing him from the need to earn a living through law or any other profession. He could now fully dedicate himself to his true passion: art. He had already begun formal art training, studying under the academic painter Léon Bonnat, known for his portraiture. Bonnat's studio provided him with technical grounding, but Caillebotte soon gravitated towards the more radical artistic ideas emerging outside the official Salon system.

Embracing the Impressionist Avant-Garde

Caillebotte's entry into the Impressionist circle was facilitated by his growing connections within the Parisian art world. He met several artists associated with the group, including Edgar Degas and Giuseppe De Nittis, likely through introductions from mutual acquaintances. He was drawn to their commitment to depicting modern life and their innovative approaches to light and color, even though his own style retained a more solid, realistic foundation.

His official debut with the Impressionists occurred at their second group exhibition in 1876. This followed the rejection of his painting, The Floor Scrapers (Les Raboteurs de parquet, 1875), by the jury of the official Salon earlier that year. The Salon jury deemed the subject matter – bare-chested urban laborers scraping a wooden floor – too "vulgar" and unrefined for academic tastes. Undeterred, Caillebotte submitted the work to the Impressionist show, where it garnered significant attention, marking him as a bold new talent aligned with the avant-garde.

From 1876 onwards, Caillebotte became a core member and energetic participant in the Impressionist group. He exhibited regularly, participating in five of the eight Impressionist exhibitions: 1876, 1877, 1879, 1880, and 1882. He submitted a substantial number of works to these shows, showcasing his unique perspective on Parisian life, landscapes from Yerres, portraits, and still lifes.

His involvement extended far beyond simply exhibiting his own paintings. Leveraging his considerable wealth and organizational skills, Caillebotte played a crucial role in financing and organizing several of the Impressionist exhibitions, particularly the pivotal third exhibition in 1877 held in an apartment on the rue Le Peletier, which he largely funded and helped arrange. He acted as a unifying force within the often-fractious group, mediating disputes and encouraging participation.

A Unique Artistic Vision

Caillebotte's art occupies a fascinating space between Realism and Impressionism. While he shared the Impressionists' interest in modern subjects, contemporary urban experience, and the effects of light, his technique often differed significantly. Unlike the broken brushwork and emphasis on fleeting atmospheric effects favored by artists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Caillebotte frequently employed a smoother finish, precise drawing, and a more structured composition reminiscent of his academic training under Bonnat.

What truly set Caillebotte apart was his innovative use of perspective and composition. He was fascinated by the visual drama of the newly rebuilt Paris, shaped by Baron Haussmann's massive urban renewal projects. His paintings often feature plunging perspectives, high vantage points looking down onto streets and bridges, dramatic cropping, and asymmetrical arrangements. These techniques, possibly influenced by the burgeoning art of photography and the aesthetics of Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), created a sense of dynamism, immediacy, and sometimes unease, perfectly capturing the scale and energy of the modern metropolis.

His subject matter centered on the life of the Parisian bourgeoisie, to which he belonged, but also extended to the depiction of labor and the city's infrastructure. He painted scenes of domestic interiors, family portraits, leisurely activities like boating and gardening, and, most famously, the streets, bridges, and apartment buildings of Paris. His figures often appear absorbed in their own worlds, reflecting the anonymity and psychological distance characteristic of modern urban existence. He masterfully captured the play of light and shadow, whether on rain-slicked boulevards, sun-drenched balconies, or the polished surfaces of interior floors.

Masterpieces of Modern Life

Caillebotte produced several works that have become icons of late 19th-century art, offering profound insights into the visual and social fabric of his time.

The Floor Scrapers (Les Raboteurs de parquet, 1875): This groundbreaking work, rejected by the Salon but embraced by the Impressionists, depicted working-class men engaged in manual labor within a bourgeois apartment. Its realistic portrayal, unusual perspective looking down on the figures, and focus on an "unheroic" modern subject challenged academic conventions. It drew comparisons to the Realism of Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, but with a distinctly urban and contemporary focus.

Le Pont de l'Europe (The Bridge of Europe, 1876): This painting captures the complex iron structure of the bridge spanning the railway tracks near the Gare Saint-Lazare, a hub of modern transportation. Caillebotte masterfully uses the bridge's geometry to create a dynamic composition. Figures, including a top-hatted flâneur (stroller or observer of urban life) resembling Caillebotte himself, and a worker leaning on the railing, populate the scene, hinting at the social strata coexisting in Haussmann's Paris. The play of light and shadow across the metalwork and pavement is rendered with precision.

Paris Street; Rainy Day (Rue de Paris, temps de pluie, 1877): Perhaps Caillebotte's most famous work, this large canvas depicts a complex intersection near the Gare Saint-Lazare on a wet day. The plunging perspective, the dominance of wet cobblestones reflecting the grey light, and the cropped figures with their umbrellas create a powerful image of urban anonymity and atmosphere. The composition feels almost photographic in its framing and sense of a captured moment, yet it is meticulously constructed. It epitomizes the experience of navigating the modern city.

Young Man at His Window (Jeune homme à sa fenêtre, 1875): This painting features Caillebotte's brother René looking out from the family's apartment onto the Boulevard Malesherbes. The strong contrast between the dark interior and the bright exterior, the high viewpoint, and the theme of observation capture a sense of bourgeois confinement and the detached gaze of the urban observer.

Man on a Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann (Homme au balcon, boulevard Haussmann, 1880-81): Revisiting the theme of the observer, this work places a man (possibly Caillebotte) on a balcony overlooking the bustling boulevard below. The high angle and the focus on the individual contemplating the city reinforce themes of modern perspective and the relationship between private and public space.

Beyond these urban scenes, Caillebotte also excelled in depicting the family estate at Yerres, capturing boating parties on the river with a lighter palette and looser brushwork closer to mainstream Impressionism. His later works often focused on the garden he cultivated at Petit-Gennevilliers.

The Indispensable Patron

Caillebotte's role as a patron and collector was arguably as important as his contribution as a painter. His substantial inheritance allowed him to support his Impressionist colleagues during a time when their work was often ridiculed by critics and ignored by collectors. He did this not merely out of charity, but from a genuine belief in the artistic importance of their work.

He regularly purchased paintings directly from his friends, often paying generous prices to help them through financial difficulties. His collection grew to include masterpieces by the leading figures of the movement. He was a particularly crucial supporter of Claude Monet, famously paying the rent for Monet's studio on several occasions and acquiring numerous key works, including several paintings from the Gare Saint-Lazare series.

He also acquired significant works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, and Berthe Morisot. His support extended beyond purchases; he actively participated in organizing and funding their independent exhibitions, helping them bypass the restrictive official Salon system and present their work directly to the public. His calm demeanor and financial backing often helped maintain cohesion within the group, which was frequently beset by internal disagreements.

Caillebotte also used his influence and resources to advocate for artists beyond the immediate Impressionist circle. Notably, he played a key role in the public subscription campaign organized by Monet to purchase Édouard Manet's controversial painting Olympia (1863) for the French state after Manet's death, ensuring this seminal work entered the national collection (initially at the Musée du Luxembourg, later the Louvre, and now the Musée d'Orsay).

Building a Legacy: The Caillebotte Collection

Through his consistent patronage, Caillebotte assembled one of the finest collections of Impressionist art of his time. He possessed a keen eye and acquired works that are now considered iconic examples of the movement. His collection included Renoir's Bal du moulin de la Galette, Degas's pastels of dancers, Monet's station scenes and landscapes, Pissarro's views of Pontoise, Sisley's depictions of the Seine, and early works by Cézanne.

He understood the historical significance of this art long before it achieved widespread recognition or market success. His collection was not merely an accumulation of assets but a curated testament to the artistic revolution he witnessed and participated in. This foresight would prove crucial for the public appreciation of Impressionism after his death.

Reflections of Society

Caillebotte's paintings serve as invaluable documents of Parisian society during the Third Republic. His works capture the physical transformation of the city under Haussmann, with its wide boulevards, imposing apartment buildings, and modern iron bridges forming the backdrop for his scenes. These settings are populated by the inhabitants of this new urban landscape.

He frequently depicted the activities and environment of his own class, the affluent bourgeoisie – their elegant interiors, leisurely pursuits, and detached observation of the city from balconies and windows. Yet, he did not shy away from depicting the working class, as seen in The Floor Scrapers or the figures glimpsed on Le Pont de l'Europe. His work subtly explores the interactions, or lack thereof, between different social strata within the shared public spaces of the city.

Themes of observation, perspective, and the psychological effects of the modern environment run through his oeuvre. The recurring motif of figures looking out of windows or from balconies suggests both a fascination with the spectacle of the city and a sense of alienation or separation from it. The dynamic, sometimes disorienting perspectives mirror the rapid pace and scale of modern life. His paintings often convey a quiet melancholy or tension beneath the surface of everyday scenes, reflecting the complexities and anxieties of his era.

Later Life at Petit-Gennevilliers

In the early 1880s, Caillebotte's intense involvement with the Impressionist exhibitions began to wane, partly due to internal conflicts within the group. In 1881, he acquired property in Petit-Gennevilliers, a suburb northwest of Paris on the banks of the Seine, opposite Argenteuil, a location famously painted by Monet. He spent increasingly more time there, eventually moving there permanently with his brother Martial in 1888.

While he continued to paint, his output decreased, and his focus shifted towards other passions. He became an avid gardener, designing and cultivating an elaborate garden on his property, which became a frequent subject of his later paintings. These works often display brighter colors and looser brushwork, showing the continued influence of his Impressionist friends, particularly Monet, who was himself creating his garden at Giverny.

Caillebotte was also a passionate yachtsman. He used his engineering skills and artistic eye to design and race sailboats, becoming highly successful in the regattas held on the Seine. He established a shipyard near his home and produced several innovative racing yacht designs. Alongside gardening and sailing, he also developed an interest in stamp collecting (philately).

During this period, he maintained a long-term relationship with Charlotte Berthier, a woman of a lower social class, to whom he left a substantial annuity in his will, although they never married. He remained close to his surviving brother, Martial, who was also an accomplished musician and photographer.

An Untimely Death and Enduring Bequest

Gustave Caillebotte's life was cut tragically short. On February 21, 1894, while working in his beloved garden at Petit-Gennevilliers, he suffered a stroke (diagnosed as pulmonary congestion or embolism) and died suddenly. He was only 45 years old. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

His death revealed the full extent of his foresight as a collector and his enduring commitment to his fellow artists. His will stipulated that his remarkable collection of Impressionist paintings be donated to the French state, with the condition that they be displayed first in the Musée du Luxembourg (then the museum for living artists) and later in the Louvre.

This generous bequest, however, met with fierce resistance from the conservative elements of the French art establishment, particularly the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Figures like the academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme vehemently opposed the acceptance of works they considered unfinished and unworthy of national recognition. After protracted negotiations, led by Caillebotte's brother Martial and his friend Renoir acting as executor, the state finally agreed to accept a portion of the collection in 1896 – thirty-eight paintings, including seminal works by Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, Sisley, and Cézanne. Although some works were refused, the accepted paintings formed the nucleus of the national collection of Impressionist art, eventually finding their permanent home in the Musée d'Orsay. This act cemented Caillebotte's legacy not just as an artist but as a crucial figure in the preservation and public acceptance of Impressionism.

Caillebotte's Place in Art History

For much of the 20th century, Gustave Caillebotte's reputation was somewhat overshadowed by his role as a patron and by the fame of the artists he supported. His own paintings were less widely known, partly because many remained in private hands within his family. However, beginning in the mid-20th century, his work began to be reassessed and appreciated for its unique qualities.

Today, Caillebotte is recognized as a major painter in his own right. His distinctive blend of realistic detail and modern perspective offers a compelling vision of late 19th-century Paris. His iconic images, such as Paris Street; Rainy Day and The Floor Scrapers, are celebrated for their artistic innovation and their insightful commentary on urban life. His crucial role as a financial supporter, organizer, and collector for the Impressionist movement is now fully acknowledged as indispensable to the group's success. Gustave Caillebotte remains a testament to the power of individual vision and generosity in shaping the course of art history.